A Strategic Perspective on Sales Promotions

How to plan profitable sales promotions by considering the stature of your brand in the marketplace, the message being delivered, and how customers and competitors will react.

While most managers would think long and hard before bringing to market a product that lacked patent protection and could be easily imitated, many invest in sales promotions — sweepstakes, coupons, time-limited price discounts, free gifts or samples, special events, displays, membership rewards, consumer-directed promotions and so on — that are easier to imitate than the simplest new product. Others sign off on plans so generic that they seem unrelated to the brand or company offering them, despite the fact that sales promotions may absorb a significant portion of a company’s promotional dollars — currently a reported 31% of marketing budgets1 — and they are increasingly being used for both packaged goods and consumer durables as concern has grown about the cost effectiveness of media advertising.2

For example, the “you pay what we [employees] pay” price promotion instituted by General Motors Corp. during the summer of 2005 was imitated after only five weeks by its two major U.S. rivals. Analysts estimate that the promotion cost GM an average of more than $5,000 per vehicle3 through its September 30 termination, contributing to a $4 billion loss on North American operations during the first nine months of 2005.4 The full year was marked by a 50% decline in GM stock value and a 4% decline in sales vs. 2004.5

The unhappy outcomes for GM — and similar ones for imitators Daimler-Chrysler and Ford — illustrate the negative consequences of easy-to-copy promotions, but this example is hardly unique. An analysis of 20 years of research evaluating sales promotions indicates that most such promotions do not pay off, and even the studies painting a happier picture find no more than 60% earning back their costs.6

In contrast, a strategic focus leads to promotions that defy or delay imitation and yield disproportionate benefits for companies that have already developed a strong competitive position. For a fraction of the cost of the “you pay what we pay” promotion, any automobile marketer — or any other marketer — has a range of promotional tools to consider. For example, both the Pontiac and Cadillac divisions of GM reported successful promotions in 2005 that did not involve discounts. Pontiac used an episode of Donald Trump’s “The Apprentice” television show to have two teams compete in producing brochures for the 2006 Pontiac Solstice, a new model compact convertible. Viewers were offered an early chance to purchase the Solstice, and with the help of supplementary web promotions, Pontiac presold 7,116 cars to become the market share leader in the compact convertible category.

Cadillac sponsored a Super Bowl post-game show to promote the ability of its V-Series cars to hit 60 miles per hour in less than five seconds. The company created a special Web site promoting a “Five Second Film Competition,” then invited site visitors to shoot and upload a five-second film on any topic. More than 2.5 million consumers visited the page, 2,600 of whom submitted films. Cadillac reported in its award-winning “Reggie” entry that in the four months following the promotion, sales of the Cadillac V-Series jumped by 25%.7

A clearer contrast to GM’s summer price promotions could hardly be imagined. These were successful promotions that no competitor even tried to imitate, given their unique ties to the brand images created by Pontiac and Cadillac, respectively.

Any sales promotion worth its salt will increase sales, but creating a profitable promotion is more difficult.8 Indeed, successful promotions are most often those that consider how customers and competitors will react to any promotional effort, as well as the message delivered and the brand’s stature in the marketplace. To help managers align those factors in planning profitable sales promotions, this article will analyze successful and unsuccessful promotions — and what differentiates them. (See “About the Research.”)

Whether designed for consumers or for organizational buyers, it appears that a successful promotion has these features:

It provides the sponsor with a period of exclusivity because it precludes or delays imitation but encourages quick buyer response.

This criterion is the most critical in avoiding promotional losses. Difficulty of imitation may occur either because of a unique association of the promotion with its sponsor or because some hard-to-duplicate resource makes imitation difficult. Quick buyer response is encouraged by a promotion that is simple to understand, ideally with informative elements or emotionally appealing components or both.

It does not rely on discounting alone, but communicates something about the company, the brand, or the specific goods or services offered.

It informs potential purchasers or creates an emotional bond, even if the message connecting the brand to the potential buyer is conveyed indirectly.

It is launched by companies that have some differential advantage in the marketplace already.

Sales promotions don’t create that advantage as much as they exploit it.

Deterring Imitation but Attracting Buyers Quickly

An easily imitated promotion, like a time-limited price cut or reward program based on purchase frequency, can result in a lose-lose outcome both for the originating company and for its imitators. Depending on the type of promotion, imitation can not only reduce profitability — it can even reduce per-unit sales revenue. If a temporary price promotion is more than matched by competition, an escalating price war can lower prices throughout a product category.

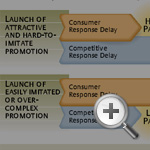

That danger suggests that price promotions should be adopted only with great caution. Certainly longer term price reductions can be valuable competitive tools when they expand the total market for a product category, promote trial for a brand with a distinct but hard to communicate advantage, or discourage competitors from entering a category. However, a price promotion is by definition a short-term cut, and many such promotions accomplish little more than inviting imitation and reducing profits. Their primary advantage, accounting for their frequent use, is that buyers understand price promotions easily and so can respond quickly. Ideally, promotions are designed with consideration of the time gaps between initiation of a promotion and two subsequent events: significant response by a target audience and imitation by competitors.

Realistically, maximizing the “monopoly window”— the time between consumers’ response to a promotion and competitors’ reaction to it — involves trade-offs, because the simplicity and ease of communication that speed up a consumer purchase will likewise normally speed up imitation. (See “The Monopoly Window.”) Conversely, promotions designed to be difficult to mimic may also be difficult for targeted individuals to understand, and thereby may delay customer response. Furthermore, promotions designed for implementation by channel partners — distributors or retailers, for instance — must be simple enough so that those channel partners are motivated and able to implement them, an effort often made more complex if those partners span the globe.9

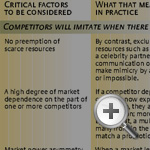

Given these conflicting priorities, managers increase the likelihood of successful sales promotions when they “buy time” by employing elements that are scarce or difficult to acquire and incorporating complex linkages with third party providers that are difficult to imitate. (See “Predicting Imitation of a Promotion and Speed of Consumer Response.”) Among the factors that predict competitive imitation of promotions, preemption of scarce resources ranks high as a way to preclude imitation.

Developing a strategy for preventing promotional imitation is of course most important when imitation of a promotion by rivals is most likely. The best clues to such a likelihood come from research on imitation of pioneering new products. Such research identifies as factors that increase imitation (1) a high degree of market dependence on the part of the competitor,10 (2) market power asymmetry in favor of the competitor, and (3) a high degree of perceived similarity between the competitor and the pioneer.11 In other words, an underdog brand in a category where the leading brand is similar and is vital to its parent company’s profitability is likeliest to face promotional competition. Managers responsible for such brands are thus most strongly advised to consider the strategic considerations presented here and the methods utilized by award winning promotions to compete successfully.

The Home Depot Inc. provides an example of a promotion that was difficult to copy. In 2004, the Atlanta-based retail chain increased Web site and store traffic by employing 450 athletes training for the Olympic Games and the Paralympic Games. By offering a flexible work week with full-time pay and benefits to the athletes, who “donned orange aprons and worked in aisles of Home Depot stores,” the chain cemented an association with the Olympic Games that differentiated it from other Olympic sponsors and certainly from its retail competitors. Its reported results included publicity at a level equivalent to having every American hear or see its story twice, plus 40,000 registrations at its Web site.12

A far more common promotion — offering loyalty bonus points — offers another example of the need to gain a differential advantage through preemption, since rivals will either have similar promotions underway or are likely to initiate them. The key to creating a bonus points program that is the least vulnerable to competition is communicating the idea that as spending increases, the reward per dollar spent increases even more: A shopper who spends $100 in a given month at a particular chain, for example, earns double “reward points” for every dollar spent thereafter in the same month. While any retailer can institute such a promotion, the one who couples it with a New Year’s Day or April Fools’ Day food festival to attract shoppers on the first day of the month starts out with a substantial number of buyers reaching the $100 threshold. Such a tactic exemplifies the multiplier effect inherent in many excellent plans: A sales promotion works most effectively when the brand attracts interest for more than the “buy now” offer alone.

Speeding Consumer Response

The uniqueness of the Olympics protected the Home Depot promotion from duplication. However, sponsors such as retailers with loyalty programs expect that rivals will simply be delayed from imitation, not precluded entirely. Thus, however difficult or easy a promotion may be to imitate, wise managers design promotions not only to delay imitation but to accelerate consumer response.

What factors influence consumers to act quickly? Promotions elicit purchase by tapping into one or more of three types of motivations: economic, informational and affective. Economic incentives make a purchase less expensive in money and/or in time and effort. Information influences consumers’ beliefs about the brand or product category. The affective approach arouses favorable feelings and emotions and associates them with the promoted brand.13

The best way to increase success for a promotion is to structure it to supply all three motivations. An example of this kind of “triple threat” is the promotion for Procter & Gamble Co.’s Pampers Feel ’n Learn Advanced Trainers, described by P&G as the next step up from disposable diapers for children ready to “graduate” to toilet training. P&G set out to “empower” these toddlers “as they learn to anticipate a potty urge” with cutting edge technology that allows children to actually feel when they are wet.

The sales promotion mechanism was to declare August “We Can Do It” month. A partnership with five other toddler brands included special offers and store displays including “I’ve Got the Power” motion-activated “talking shelves.” Stores offered training kits in English and Spanish, and 417 day-care centers in the Chicago test market received kits along with potty training tip booklets and discount coupons for parents.

Thus, the promotion combined the economic impact of saving money with information on training toddlers out of diapers and the emotional “plus” of toddler empowerment — all magnets to speed trial of the brand by the mothers whom P&G targeted. Also, the promotion’s linkages with third party providers increased its complexity, deterring imitation. Results included a reported 4.9 share point increase for Pampers and a product trial rate that was 7 percentage points higher among day-care test respondents versus a control sample.14

Some promotions can be very successful by employing only one or two types of motivation. Often, an informational approach seems unnecessary, for instance, and a sponsor simultaneously offers a “deal” while communicating to produce an emotional link between the company’s brand and the consumer.

One such mechanism is to invite that consumer to, in effect, “join our exclusive club,” with the assumption that customers who establish such a bond to a product or service provider will see no need to shop elsewhere. Among recently reported successes:

- An Italian restaurant offered “valued members” a pint jar of the house spaghetti sauce annually in return for a $15 membership fee. The sauce was presented to them during a meal at the restaurant, so that nonmember patrons could watch the presentation and presumably decide they too should “join the club.”

- Pizza Hut, a subsidiary of YUM! Brands Inc. of Louisville, Kentucky, offered a large pizza to customers joining its VIP (Very Into Pizza) group for $14.99. The company also provided an additional free large pizza for every two $10 orders and a monthly order of free bread-sticks or baked cinnamon sticks.

The Pizza Hut VIP promotion increased members’ incremental orders by 93% in 2005 and raised incremental net sales by 65% in stores using the program.15 It therefore offers an instructive example of an astute trade-off between complexity and simplicity. To have announced “VIP members get free pizza” would have been simpler, but that would not have explained the full nature of the Pizza Hut offer and would have made imitation easy. By describing the promotion more fully, the pizza chain chose complexity and deterrence of imitation over simplicity of communication, with successful results.

Winners Benefit Disproportionately

The third principle we infer from examining successful promotions is the disproportionate benefit accruing to brands that have some other “plus” factor besides the promotion itself. One such factor is the perceived quality level of the brand sponsoring the promotion. Researchers have found that consumer switching is not symmetrical, but that promotions of brands with greater brand equity bring about more switching than do promotions of less distinguished brands.16 In other words, promotions accentuate perceived quality advantages rather than overcoming quality disadvantages. However, these same researchers caution that market share should not be used as a proxy for perceived quality. If a firm has “bought” market share through its pricing strategy or distributional advantages, there is no reason to attribute share leadership to perceived quality and therefore no reason to expect a differential advantage from even the best sales promotion efforts. Still, a well-planned promotion can build brand equity while making “buy now” an attractive proposition.

An example is a trade promotion directed to truck fleet owners by Cummins Inc., a global supplier of diesel engines based in Columbus, Ohio. In 2003 and 2004, the company responded to stepped-up U.S. Environmental Protection Agency emission regulations by developing a new technology, while its largest competitor lobbied to delay implementation of the regulations, claiming that the new technology would cause problems. Cummins offered an “uptime guarantee” to build confidence in the reliability of its engines, publicized at major trucking trade shows and through trade publications, but implemented through channel partners. If a customer had a problem with a Cummins engine, the Cummins dealer or distributor would reimburse the customer for a rental truck for up to three days so the delivery could be completed.

The Cummins promotional program boosted this already well-respected firm to record sales and an industry-leading share in North America for the first time in five years.17 Clearly, that successful outcome required no particular complexity to achieve, but it required an astutely designed promotion that its largest competitor could not imitate without a complete “about face” on its stance concerning the EPA regulations.

Cummins’ success illustrates the double payoff from a pioneering promotion that upgrades a brand’s image. A company that pioneers can often exert a significant influence on consumer learning and preference formation because that company temporarily monopolizes buyers’ attention. While its competitor’s back was turned, Cummins was able to dramatize the association of its engines with reliability. More generally, the monopoly window that exists before competitors imitate a promotion lets the pioneer foster both familiarity with and preference for the benefits and associations that the promotion creates.

Additional Lessons

In addition to the three principles outlined above, analysis of successful promotions suggests a number of other lessons:

Avoid Imitation

Not only is it a mistake to launch a promotion that can be imitated easily, but from the perspective of the imitator, a copycat promotion also is likely to be a mistake. The originating company may counter by escalating its deal, incurring losses for the originating company and the imitators, and trapping all competitors because none wants to stop the promotion first. Also, imitators may find that potential buyers associate a copycat promotion with the original promoter’s brand.

Plan for Contingencies

Given the downsides of imitation, sensible managers will undertake contingency planning: If our competition launches Promotion X, we will launch Promotion Y. This kind of contingency planning seems particularly valuable in a business-to-business marketing context, where price promotions offered to one customer can be demanded by a competitor of that customer and matched almost instantly, eliminating the profitable “monopoly window.”

Managerial Challenges

The discussion presented here simply advocates considering how customers will react and how competitors will react to any promotional effort, as well as the message delivered and the stature in the marketplace of the brand delivering it. When all of these factors are aligned, the result is a successful promotion. However, two aspects of what we have recommended work against adoption of these ideas in many organizations, posing internal challenges for managers:

Overcoming the Comfort of Imitation

In some corporate cultures, marketing managers will encounter resistance to originality and innovation from others who ask for evidence of expected outcomes. If a company re-uses last year’s promotion, there is some basis on which to forecast the results. If a company imitates what others have done, there is likewise greater certainty than with a novel approach. Thus, a manager may face opposition in attempting the kind of promotion described here, which by definition will most often lack a “track record.”

Overcoming the Resistance to Speed

The approaches advocated here often require moving fast. In some organizations, the need for speed, to preclude competition or to seize an opportunity, doubles the intraorganizational doubts: Not only is it unclear what a promotion will accomplish, but those who want to launch it are in a hurry. That alone may elicit resistance in some organizational settings.

Marketing managers in resistant organizations not only must tailor a promotion successfully to its intended market, they must also skillfully shepherd it around internal barriers. Knowing why, how and for whom sales promotions will most likely be profitable — the kind of strategic approach recommended here — will surely help.

References

1. The Promotion Marketing Association issued its “7th Annual State-of-the-Promotion Industry” report in 2005; however, its numbers, the most recent available, extend only through 2004. It published two methods of calculating spending; we have used the more conservative. The alternative allocates $515 billion in promotional spending among consumer promotion (44%), trade promotion (27%) and advertising (29%).

2. J.A. Quelch, S.A. Neslin and L.B. Olson, “Opportunities and Risks of Durable Goods Promotion,” Sloan Management Review 28 (winter 1987): 27–38.

3. J.B. White and J. McCracken, “Auto Industry, at a Crossroads, Finds Itself Stalled by History,” Wall Street Journal, Jan. 7, 2006, A1, A5.

4. M. Maynard, “Kerkorian Aide Tells G.M. to Be More Like Nissan,” New York Times, Jan. 11, 2006, C1, C4

5. M. Maynard and J. Brooke, “Toyota Closes in on G.M.,” New York Times, Dec. 21, 2005, C1, C14.

6. D.M. Ruch, “Effective Sales Promotion Lessons for Today: A Review of Twenty Years of Marketing Science Institute-Sponsored Research,” Report No. 87-108 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Marketing Science Institute, 1987).

7. Both Pontiac and Cadillac were 2006 “Reggie” winners.

8. P. Raghubir, J.J. Inman and H. Grande, “The Three Faces of Consumer Promotions,” California Management Review 46, no. 4 (summer 2004): 23–42.

9. L.S. Simpson, “Enhancing Food Promotion in the Supermarket Industry: A Framework for Sales Promotion Success,” International Journal of Advertising 25, no. 2 (2006): 223–245.

10. M.J. Chen and I.C. MacMillan, “Nonresponse and Delayed Response to Competitive Moves: The Roles of Competitor Dependence and Action Irreversibility,” Academy of Management Journal 35, no. 3 (1992): 539–570.

11. K.G. Smith and C.M. Grimm, “A Communication-Information Model of Competitive Response Timing,” Journal of Management 17, no. 1 (March 1991): 5–23.

12. Promotion Marketing Association (PMA) “Reggie” awards (2005). Reggie awards are named for the cash “regi”ster, emphasizing the point that sales promotions are intended not simply as image builders but as builders of sales. The annual awards are made jointly by the Promotion Marketing Association and Brandweek magazine. Other promotion awards can be accessed at http://promomagazine.com/resourcecenter/campaignshowcase.

13. Raghubir, Inman and Grande, “Three Faces.”

14. PMA “Reggie” awards.

15. S. Coomes, “Meaningful Rewards,” Dec. 22, 2005, http://www.pizzamarketplace.com/article.php ?id=4565&prc=149&page=135.

16. R.C. Blattberg, R. Briesch and E.J. Fox, “How Promotions Work,” Marketing Science 14, no. 3 (1995): G122–G132.

17. Cummins was another 2005 “Reggie” awards winner.