Boundary-Setting Strategies for Escaping Innovation Traps

Smartly placed, legitimizing constraints actually enable innovation by focusing it and giving it traction in the competition for corporate attention and resources.

Topics

Like many CEOs, Andy Grove missed the boat on the Internet. The longtime CEO of Intel Corp. explains that he was simply too busy with the microprocessor business, which was doing extremely well in the mid-1990s.1 Similarly, Microsoft Corp.’s preoccupation with its release of Windows 95 initially blinded it to the vast potential of the Internet as a business proposition. The truth is, emerging opportunities for innovation are often obscured by current business concerns. For managers who have many competing demands for their attention,2 short-term needs and goals are often more pressing and absorbing than long-term possibilities.3 In attempting to run their companies to the best of their abilities, executives can paradoxically make themselves vulnerable to a variety of “traps” that actually forestall innovation.

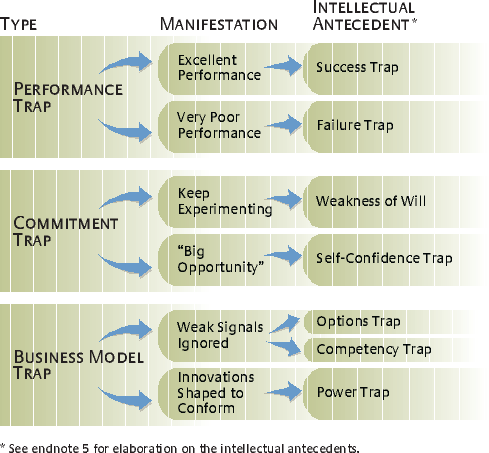

In our work (see “About the Research.”), we have identified three common innovation traps that can ensnare managers at large established companies, particularly when radical rather than incremental innovation is called for.4 These are the performance trap, the commitment trap and the business model trap. These categories dovetail nicely with much of the existing management literature on the subject. (See “The Innovation Traps.”)5

The Performance Trap.

As in the cases of Intel and Microsoft, companies that currently perform well and enjoy sufficient growth in their core business tend to overlook opportunities that in the long term may be crucial to them. Either they lack financial incentives to explore these innovations,6 or the exploitation of such opportunities may be disruptive or require timely action by the management, which is already fully preoccupied with managing ongoing, fast growth. For example, Sun Microsystems Inc. may have lost market share to the Linux operating system due to its reluctance to embrace the open-source technology, even though it would have been in a great position to do so given Sun’s history in UNIX technology and its engineers’ commitment to work on open-source projects in their free time.7 The performance trap can also occur when a company has fallen into a crisis mode; it will tend to retrench, emphasizing cost cutting and other emergency measures that provide short-term relief, rather than looking for opportunities for future growth.

The Commitment Trap.

This occurs when there is too much or too little commitment to a particular innovation. If a “keep experimenting” mind-set prevails, the management shies away from any real commitment to innovation, so it remains in its early phases as an idea, experiment or prototype. More market research must be done, more technical analyses completed, or it is never deemed quite the right time to invest in the opportunity. Thus, as a result of a series of excuses that testify to the management’s lack of courage or vision, the innovation fades away. By contrast, a company with a “big opportunity” mind-set identifies an innovation as a major opportunity and invests major resources in it without sufficient testing. By the time the unlikelihood of the innovation’s maturing into a successful business becomes apparent, the company has overcommitted itself to the point where withdrawal and disinvestment would be expensive, and credibility, careers and reputations are at stake.

The Business Model Trap.

This is most evident when a company seeks innovations that require drastically different business strategies and competencies. Disruptive technologies not only require new technical capabilities; they often imply a different business model in which those technical capabilities become commercially valuable.8 When radical innovations are adopted but they are shaped to conform to the requirements of business as usual, their potential is lost or curtailed.9

In addition, many authors have noted that companies are often manifestly aware of imminent change in the competitive environment but are unable to accommodate the implications in their business focus. By the time the environmental shift has become pervasive, the company often finds itself lacking effective strategic options. Of course, even when such options have been generated, the organization still needs new competences to execute them. Thus the business model trap is perhaps the most complex innovation trap. It overlaps to some extent with both the performance trap and the commitment trap in that a pervasive shift in the environment requires the ability to commit to alternative options while the company’s performance still allows the acquisition of new competencies through experimental strategies.10 Such a business model transformation is difficult, particularly if the company still earns revenues through its old business model and thus has an incentive not to undergo a major transformation.

Setting Boundaries to Free Innovation

Our research indicates that companies avoid innovation traps by, paradoxically, placing boundaries on their innovation activity. In an environment without boundaries, it is difficult to orient or anchor one’s thinking or avoid being perceived as “off the wall,” as there is no context for shared interpretation or common expectations. “You need to have boundaries in order to describe an innovation,” says Pertti Kärkkäinen, head of Nokia Research Center, USA. Such boundaries are not a constraint but a precondition for effective innovation, an aid to defining innovation needs and producing useful outputs that business units can exploit. Smartly placed, legitimizing constraints actually act as enablers of innovation by making it more palatable and execution friendly and giving it traction in the competition for corporate attention and resources.

Certainly, not all boundaries are conducive to innovation, but it is important to bound innovative initiatives in such a way that innovators do not become overwhelmed by the scope of the challenges. In that context, innovative success is defined in terms of small wins, and problems are continually reframed so that new solutions can be attempted.11

A number of companies we have studied employ effective strategies for bounding innovation and thereby escaping the myopia that could trap them in their current business activities and strategies. This does not suggest that escaping myopia necessarily or automatically leads to successful corporate performance. Performance is far too complex an outcome to be explained by any one factor alone, and it may be influenced by factors unrelated to the company’s innovation capability. Nevertheless, not escaping such innovation traps is certain to lead to poor performance sooner or later.

Nokia Makes Innovation Urgent

In 2002, Finnish communications equipment vendor Nokia Group12 achieved net income of €3.4 billion on sales of €30.0 billion. Its average annual return on investment for the past five years has been 33.2% — almost triple the 12.8% average for S&P 500 companies. The company employs some 52,700 people (including 19,500 people in research and development), with production facilities in 10 countries and sales in 130 countries.

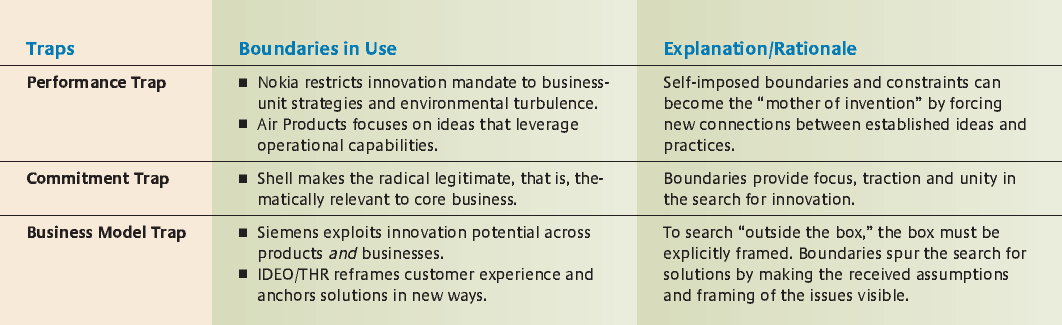

Nokia has sought to escape the performance trap by focusing its innovation efforts on business-unit strategies and opportunities where patterns of user behavior, technologies or industry structures are in flux. In 2002, Nokia Ventures Organization was a recent addition to the Nokia Group. Its mission was to generate new business ideas outside Nokia’s current focus as well as to contribute to the growth of the company’s existing core businesses. At the time of our study, Nokia Ventures Organization included several constituents: two incubated business ventures (Nokia Internet Communications and Nokia Home Communications); an opportunistic venture capital fund (Nokia Venture Partners), which had invested in notable start-ups such as Pay-Pal (acquired by eBay in 2002); two business accelerators for both strategic and nonstrategic ventures; and the Insight & Foresight unit, which identified opportunities by studying user needs, emerging technologies and the changing business environment within the mobility and communications space.

Pertti Kärkkäinen, then head of Nokia Research Center, USA, believed that the business units should set the boundaries for the R&D department. This way, the business units would share in the responsibility for producing useful R&D outputs. Moreover, boundaries related to the business concept could help the R&D department understand its mission and produce useful outputs for the business units, thus linking R&D closely to competitive strategy.

Meanwhile, Nokia Ventures Organization sometimes faced the tough challenge of trying to persuade a recalcitrant business unit to pay more attention to a particular business opportunity. Jarkko Sairanen, the head of the Insight & Foresight unit, called this the “not-invented-here syndrome.” Nokia Ventures Organization addressed the problem in several ways — by being persistent, by getting the business units involved early in the study of emerging opportunities so that they developed a sense of ownership of the opportunity and by incubating a business venture itself for as long as necessary before the business unit was ready to embrace the opportunity. In spite of their challenges, Nokia Research Center and Nokia Ventures Organization had been effective in their innovation and renewal missions. For example, the research center’s foresight had helped to position Nokia in the vanguard of the emerging Internet protocol–based cellular technologies. And Nokia Ventures Organization had brought opportunities in wireless local area networks and digital-rights management to the attention of Nokia Networks and Nokia Mobile Phones, respectively.

Air Products Leverages Existing Capabilities

Founded in 1940, Air Products and Chemicals Inc. of Allentown, Pennsylvania, is a large supplier of atmospheric gases, specialty gases and chemicals with revenues of $5.4 billion in fiscal 2002. The company has operations in more than 30 countries and employs 17,200 people. During the past five years, Air Products has achieved average revenue growth of 3.0% per year.

At the end of 2001, Air Products established its Corporate Development Office, which included strategic planning, business commercialization, mergers and acquisitions, corporate economics, early business development and innovation groups. The latter group, which is led by Ron Pierantozzi, director of New Business Development and Innovation, focuses on growth ideas from new technologies and new industry domains.

For Air Products, achieving growth from outside its existing businesses is much more difficult than achieving incremental growth. Pierantozzi attributes the greater difficulty to the company’s historical focus on operational excellence and cost management. Air Products has sought to escape that performance trap by focusing on new ideas that leverage its operational capabilities. “If you try to develop an idea without having the capabilities,” says Pierantozzi, “you find that you have to develop both the idea and the capabilities, and that’s a lot harder.” For instance, Air Products was able to open a whole new market by leveraging its competence with an existing product. Semiconductor companies with which Air Products worked found it very difficult and expensive to clean the chemical vapor deposition chambers in which they fabricate semiconductor wafers. Air Products’ researchers observed that nitrogen trifluoride — a nonflammable, corrosive, toxic gas used in lasers — also reacted with inorganicmaterials, and they realized that it could solve the cleaning problem. This resulted in a more effective, environmentally friendly cleaning system.

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge now facing Air Products is to shift its corporate culture toward more radical innovation without sacrificing the virtue of operational excellence. Pierantozzi is optimistic that the company can meet this challenge: “It’s easier to teach an operationally excellent company to be more innovative,” he says, “than to teach an innovative company to be more operationally excellent.”

Shell Identifies Relevant Innovation Themes

Shell Oil Co. has sought to escape the commitment trap by defining, to the extent possible, what is legitimate innovation at any point in time. Its Exploration & Production GameChanger innovation program13 was established to answer that question. At GameChanger, the legitimate space for innovation is first divided into “relevant” and “not relevant” arenas. In the “relevant” innovation space, new growth opportunities are thought of as either logical extensions of core business activities or as “white space” ventures. White space consists of ideas that are more distant from the core business but that nevertheless draw on corporate capabilities, often from two or more different Shell businesses.

The line between what is and is not relevant has moved over time, explains Leo Roodhart, head of the Corporate Game-Changer program. A few years ago, GameChanger might have solicited ideas around notions such as urban utopia, inviting ideas ranging from commuting pools to waste reclamation. Says one of the GameChanger staff members: “I would not go out there now and try an urban utopias workshop. I’d try something closer to what we do at the moment, more aligned to the businesses.” But the boundaries are somewhat flexible: “You have to know where your envelope is and where the outer boundaries are … and just prod them.” Another staff person is not certain the direction can be reversed, though: “The line does move, but I have only seen it move one way so far.” Nevertheless, the Group GameChanger activities in 2000 seem to suggest that there is occasional room for far-out investments such as the InternetWorks, an Internet and e-business incubator, which was initiated and later closed down.

The GameChanger team uses various other methods to identify innovation boundaries. It works closely with corporate strategy and Shell Scenarios to identify critical future directions for Shell. Through these interactions, the Group GameChanger identifies relevant innovation themes such as the aforementioned urban utopia, greening the desert (finding better uses for production water) and stranded gas (finding alternative uses for gas associated with oil production without immediate markets nearby). These themes are then explored in GameChanger-sponsored ideation workshops open to anyone interested in producing ideas to feed the pipeline. By nominating a theme for innovation but not focusing on any particular solution, the GameChanger team is able to suggest relevancy yet leave the space open for creative ideas. This avoids the commitment-trap tendency of large companies to invest in a big opportunity without analyzing a number of innovative ideas within that space on their respective merits. Once a project is mature enough, corporate commitment is really tested as the project is transferred to an operating company, which must take it to its next level of funding.

Siemens Blends Corporate and Business Unit R&D

Founded in 1847, Munich-based electrical and electronic engineering conglomerate Siemens AG has grown to become an enormous corporation. It has assets of €77 billion and 2002 sales of €84 billion, and it employs 426,000 people worldwide of which some 50,000 work in R&D. In fact, with a market presence in 197 countries, Siemens is the world’s fourth-most-global organization.

Today, Siemens competes in many of the world’s most dynamic industries — telecommunications, medical technology, software and industrial automation, to name just a few — whose short cycle times require the rapid conversion of emerging technologies into new products. This fast-paced environment might encourage some companies to take a very focused approach to technology development, with all R&D conducted at “ground level,” that is, within the business units. Indeed, many companies have all but abandoned corporate R&D efforts today. In contrast, Siemens seeks to combine the R&D in its 100-some global business-unit R&D facilities with its Siemens Corporate Research14 division, which has four major laboratories at Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States and at Munich, Erlangen and Berlin in Germany. Siemens also has start-up incubators in Munich and Berkeley, California.

Johannes Feldmayer, Siemens chief strategy officer at the time of the interview for this article, believes corporate R&D is a way to escape the business model myopia that business units might otherwise exhibit. He seeks to create synergies between the corporate view — monitoring and developing capability in some 40 base technologies such as speech recognition or industrial automation — and the product-focused view of the business units.

To impose thematic discipline on its innovative ambitions, Feldmayer says, Siemens coalesces its efforts around three of its core values: financial stability (the company has been described as a bank with interests in engineering) and the trust that engenders, the company’s reputation for social responsibility and a companywide recognition of innovation as a key to sustainability. Those themes effectively provide definition and boundaries to the company’s varied innovation initiatives.

IDEO and THR Reframe the Customer Experience

Somewhere amid the staff shortages, reimbursement wrangles and acute financial pressures of recent years, the U.S. healthcare industry lost its way. Indeed, its very mission — the care of sick people — is increasingly completely obscured by a Tayloristic profit model that dehumanizes patients and hospital workers alike. To ameliorate the situation, a few vanguard healthcare providers have sought inspiration from collaboration with companies like IDEO, a global product design firm in Palo Alto, California, among others, that share a belief that the U.S. healthcare industry needs to reorganize around a unifying concern for the experience of patients and workers. IDEO’s work with Texas Health Resources in Arlington, Texas, which operates 13 acute-care hospitals, illustrates how reframing the customer experience can lead to innovative solutions by overcoming some of the implicit beliefs and assumptions about a business.

IDEO began its engagement with Texas Health Resources by extensively interviewing hospital workers, patients and visitors. Using a technique known as “appreciative inquiry,” these individuals were invited to relate accounts of their own hospital experiences. Multidisciplinary teams of doctors, nurses and hospital administrators then sought opportunities to leverage that knowledge to create useful innovation to improve the hospital experience. Because the IDEO facilitators who worked with the teams observed that many of the constraints that team members anticipated — for example, a lack of sufficiently intelligent IT — were artificial, they instructed team members to focus only on generating new ideas and not on the feasibility of implementing them. Ultimately, the teams were asked to prototype and test their ideas as well as build a business case that included feedback from all stakeholders.

The work spawned various innovations. One Texas Health Resources hospital recast the treatment of breast cancer patients as a holistic experience, integrating physical protocols such as chemotherapy with consideration of the patient’s psychological and emotional well-being. Another hospital addressed the quality of how, when and what patients ate — a notoriously frustrating experience for patients everywhere. Rather than sending food to patients when the kitchens are ready, the hospital has adopted a short-order restaurant model that allows patients to order meals when they’re hungry. A third hospital is working to improve navigation for hospital visitors by giving them color-coded maps at the reception desk. Now, when a nurse sees a visitor looking lost and carrying a red map, she’ll know that he’s probably trying to find the cardiology department.

As this collaborative process suggests, escaping the business model trap is often a matter of shifting the lens through which the reality is viewed. Indeed, that could be said about how innovation is achieved, in general. Viewing the hospital experience through the patients’ eyes places very different boundaries on innovation than do the usual demands of achieving efficiency in patient care. Such a focus redirects the search for innovation in patient-friendly ways, even ways that may not be medically significant but are nonetheless crucial for patients’ well-being.

How the Traps Overlap

Although the operative mechanisms of how companies bound innovation activities to escape pitfalls merit further research, the boundaries in use discussed above begin to map the territory. (See “Boundaries in Use.”) Yet it would be simplistic to claim that any company was threatened by only one trap at a time. Often, companies struggle to cope with multiple traps simultaneously. The commitment trap, if not escaped successfully, can perhaps be viewed as an indicator of troubles to come, including deteriorating performance. Once the performance of a company significantly weakens, it may be difficult to sustain commitment to innovation: Typically, either innovation projects become shut down or the management seeks to commit one big daring act, such as a major acquisition, to quickly improve the performance, and then firefighting supplants strategizing. Should a company find itself in such a position, it may be advisable for it to concentrate on transforming the business model (thus seeking to escape the business model trap), as obsolete competitive strategy may be the deeper, lasting cause of the company’s troubles.

Managerial Implications

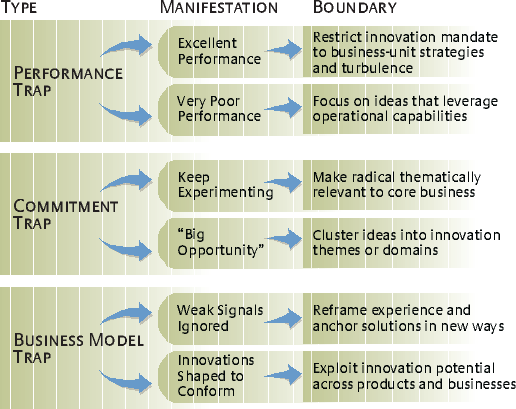

Innovation is difficult to accomplish in a large, relatively mature company, and some boundary setting strategies such as the ones described here may help the company escape the all-too-common pitfalls. But the managerial question then remains: How can managers define boundaries such that they are helpful? Some general lessons can be gleaned from the strategies presented here. (See “How to Escape Innovation Traps.”)

To avoid the performance trap — wherein ongoing success dampens the urgency for innovation — management can build urgency by tying the innovation mandate not only to aspirational business strategies but also to ongoing environmental change. This will focus attention on future rather than present performance. On the other hand, in a situation where past performance necessitates innovation-led improvement, it is beneficial to focus on new ideas that leverage existing operational capabilities. This focus will help avoid the danger of oscillating from one approach to another without allowing time for any approach to come to fruition. Leveraging operational capabilities will increase the chances that innovative ideas will succeed more quickly.

If a lack of commitment to innovation proves an obstacle, tying innovation to core business themes, thus making innovation appear relevant, may help create commitment. An additional way to increase legitimacy — and boost commitment — is to have a clearly defined innovation process that maps carefully to business proposals. To avoid the tendency of large corporations to make big mistakes by investing hundreds of millions of dollars in the quest for big innovation, it is important to develop a capability to both experiment on small ideas and to cluster individual ideas into larger opportunity domains. Within each opportunity domain it is then easier to assess the risks and merits of various innovative ideas as business proposals.

Reframing customer experience in novel ways helps escape the business model trap’s mentality of just doing more of the same. In large corporations, another aspect of the business model trap is manifested when innovation that is specific to a single business unit is forcibly applied companywide and thus loses its innovative edge. The solution is for managers to emphasize the pursuit of innovative ideas that cut across products and business units.

In the final analysis, the innovation traps discussed here are quite persistent even in the face of such tactics as dedicated venturing organizations, executive champions or linkages to operational capabilities. Such solutions are by themselves insufficient in coping with the much deeper issues of innovation resistance so common to large companies: the cognitive capacity to deny the need for change15 and the inability of a firm to commit to a systemic transformational change at the business model level before it is too late.16 Therefore the strategies in use described in this article are particularly important. They begin, in a modest but important way, to address issues that are woven deep in the organizational fabric of any large corporation.

References

1. “The Charlie Rose Show,”