Building Stronger Brands through Online Communities

The popularity of communities on the Internet has captured the attention of marketing professionals. Indeed, the word “community” seems poised to overtake “relationship” as the new marketing buzzword. So-called “community brands” like the Geocities Web site (“home” of more than three million community members “living” in 41 “neighborhoods”) provide communication media for hundreds of thousands of individuals who share common interests. As consumer-goods companies create online communities on the World Wide Web for their brands, they are building new relationships with their customers and enabling consumers to communicate with each other. Many famous brands host online communities through bulletin boards, forums, and chat rooms, such as CNN (http://community.cnn.com), Disney (http://family.go.com/boards), the Shell International Petroleum forums (www.shell.com), Pentax (www.pentax.com; see the discussion group in the U.S. section), and the Bosch tools forum on www.boschtools.com. Heineken (www.heineken.com) allows individuals to establish their own virtual bars, where, as bartender, they can chat with other visitors or meet their friends; similarly, Nescafé has a café (http://connect.nescafe.com).

In fact, the number of companies hosting consumer-to-consumer communication is escalating. Forum One, a West Coast U.S. consulting firm that specializes in monitoring consumer community sites, currently catalogues more than 300,000 online topic-based discussion boards (up from 96,000 in September 1997). Some 85% of these are operated by commercial organizations (i.e., they do not have .edu, .gov, or .org as the final suffix in their Web addresses), although many are small businesses and online retailers.1

The desire to create online communities based on brands raises many questions concerning commercial corporate objectives and their implementation, as well as issues about consumers’ willingness to participate. “Is there some power to be had in claiming a word like ‘community’?”2 If there is, and if companies can harness it, will their creation of online communities necessarily reinforce their brands? The problem is that no one can guarantee the outcome, but the potential for success is there.

To extend the brand relationships established with their loyal customers into communities of brand consumers, strategists need to examine the long-established user communities, in order to learn what makes them thrive. Strategists must also address the many issues surrounding brand-based online communities and incorporate the leadership and communication skill sets necessary to manage such communities.

From Brand Relationship to Brand-Based Online Community

Successful relationship marketing is difficult in the world of consumer services3 and grocery products, where only 20% to 30% of a buyer’s purchases in a category come from one brand.4 Fewer than 11% of the people who buy cereal, cheese, gasoline, take-home beer, and paper towels are 100% committed to a single brand in a category.5 Many more consider themselves to have a favorite brand that they buy most often from a portfolio of acceptable brands. If brand relationships are to be cultivated and managed over time, then the challenge for consumer brand owners is to devise a way to communicate that:

- customizes messages as it identifies the individual by name,

- rewards the individual for his or her continued support and interest, and

- recognizes the passage of time and a strengthening of the relationship.

If mass-market consumer brand organizations are to unlock the potential of the Web to help them form genuine relationships with their customers—relationships that are reinforcing, competitively distinctive, and long-lasting—they need to look seriously at how relationships have formed up until now on the Internet. Brand managers need to understand the bases for dialogue that can lead to strong relationships, which in turn provide the foundations for online brand communities.

Traditional User Groups

Communities of users, known as user groups, have a long history in the business-to-business world. Although user groups are more often associated with science and technology, they exist in many business sectors, including banking, insurance, real estate, and health care. The groups provide a useful forum for users to share experiences, solve problems, meet peers at conferences and events, and explore other companies and career opportunities, as well as keep current with technology and industry gossip. User groups are formed either spontaneously by buyers or at the initiation of the vendor. Spontaneously formed groups tend to have their origins in a group of local enthusiasts, such as the many user groups formed around the Macintosh computer.

Spontaneous groups are not restricted to the computer industry or the business-to-business arena. Car-marque enthusiasts run automobile clubs and organize annual shows where members display their proud possessions, trade spare parts and advice, and take part in competitions. Spontaneously formed clubs, however, can endanger a brand’s reputation, as Harley Davidson discovered when the Hell’s Angels attained notoriety for their outlaw-like behavior. Harley’s response, arguably late, was to create the more respectable and law-abiding Harley Owner’s Groups (HOGs).

The alternative to the spontaneously emerging user group is the one created and funded by a vendor to bring together its customers. For vendors, user groups offer many attractive links with key buyers and users. Vendors can contact them about new product design and product enhancements, and users often test new products. They also act as opinion leaders, providing insights into future trends and new application areas. And importantly, they act as advocates for the vendor within the company.

The Opportunities of Online Communities

In the traditional brand relationship, communication flows between the vendor and the consumer. Brand-based online communities have demonstrated the potential benefits of dialogue flowing between consumers via two utilities: real-time “chat” taking place in “chat rooms” and asynchronous discussions that play out over days, weeks, and even months in discussion forums or bulletin boards. America Online’s real-time messaging may be considered a third consumer-to-consumer communication facility. All types may exist simultaneously on a brand’s community site.

Chat rooms find favor when guest experts or well-known personalities are available to answer participants’ questions. The spontaneity and unexpected turns of chat-room discussions appeal to many participants and visitors. In comparison, the threaded-discussion format prevalent on discussion boards is easier to read since replies to specific questions are brought together under the original question. The protracted nature of discussion forums allows for more thoughtful responses and greater editorial intervention.

The popularity of interactive communication gives the brand Web site an abundance of “free” content from the consumer community. Consumers benefit from their ability to recognize in each other “people like me” and to form genuine relationships with like-minded people. Both the content and possibility of forming relationships with other buyers and with the brand’s managers act as a magnet, drawing consumers back to the site on a frequent and regular basis. This enables further commercial opportunities for the brand owners and legitimizes the investment in Web site development and maintenance. In this respect, connecting the brand site and the social aptitude of community participants potentially creates a new marketing tool.

By making sure that consumers can interact freely with each other and build a friendly online community, marketers can follow consumers’ perceptions about and feelings toward the brand in real time. The value lies precisely in the volume of communication and interaction generated between consumers. The more communication and interaction, the stronger the community, and the better the feedback. Interactive online media will enable marketers to sense market forces with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency, overcoming the limitations of today’s one-way research methods.6 Not only is such “naturalistic” research speedier, but it gives rise to more brand creativity.7 With the Web community as the brand’s neural system, brand owners are able to respond to nuances in conversations that hint at inarticulated needs. The brand’s buyers begin to set the research agenda.

New technologies are enabling the task of turning electronic discussions into useful managerial information. Tools like Artificial Life’s STAn, a smart text analyzer, are designed to help companies retrieve and analyze information from online discussions using fuzzy logic technology, neural networking, and straightforward statistical analyses (www.artificial-life.com).

Given the newness and size of the effort involved in managing a community Web site, it is tempting to outsource it to third parties, as many brand sites have done. The dangers of so doing, however, lie in the lost learning about the brand’s consumers and the lost benefits of immediacy and rapid response. Perhaps more dangerous for the longer term, out-sourcing these tasks compromises the corporation’s ability to develop a new set of skills that may ultimately become as important and integral to the marketing job as are the skills involved in marketing research or strategic planning. Developing a brand-based online community may turn out to be a more critical task than launching a new brand variant.

Why Successful Online Communities Thrive

Established communities on the Internet provide the potential brand community developer several measurements for success. These sites thrive because they offer their participants the following:

- a forum for exchange of common interests,

- a sense of place with codes of behavior,

- the development of congenial and stimulating dialogues leading to relationships based on trust, and

- encouragement for active participation by more than an exclusive few.

They Provide a Forum for Exchange of Common Interests

The Elsevier Science Group recently acquired BioMedNet, a virtual community of biologists and the medical community. The site features specialist discussion groups, a regular forum on a topical issue, a research database called Medline, a job exchange, and a daily newsletter, the HMS Beagle. The site is a research resource for the scientific community and a meeting place for specialists.

The company profits by selling advertising space on its new virtual bookshop, called Galapagos, through which it also earns sales commissions. In addition, it earns revenue through the sale of e-mail lists to advertisers. The site receives approximately 3000 registrations each week, and new members are asked if they want to receive promotions by e-mail (about 60% say “yes”). The sales and marketing director is reported as saying, “as long as the promotions are well targeted and appropriate, then people don’t mind.”8

Other types of business have also tapped into the natural gregariousness of their target audiences. In mid-1997, U.K.–based Reed Personnel Services funded its Red Mole (www.redmole.co.uk) site to attract college students to its graduate recruitment pages with a mass of serious and not-so-serious information. There, students can access a university guide in which they may rank institutions according to faculty, curricula, accommodations, and the nature of the students themselves. Red Mole students send each other more than 1200 online “moleograms” a week, choosing from a selection of 80 e-cards. They can also research essay questions by posting queries on a message board or by taking out an annual subscription ($15) to the Knowledge Exchange, which posts graded essays on a wide variety of topics. They can join a discussion group called the Nonsense Exchange or compare prices of beer in various bars across the country. At the Working Mole section, run by the Reed Graduates Division, current students can look for part-time and vacation employment, and graduating students can search listings for full-time employment with Reed’s corporate clients. With a steady stream of just under 1500 students a month linking directly from Red Mole to the Reed Graduates or Reed Online, Working Mole generates some 11,000 page impressions per month.

These communities have a distinctive focus. The audiences may be geographically dispersed and dislocated in time, but they share common interests that are perhaps difficult to serve profitably through other media.

The notion of sharing common interests also binds together the diverse and large communities in Geocities, Tripod, FortuneCity, or any of the community-brand Web sites. For example, more than three million individuals or families have spent time carefully crafting their own Geocities Web sites and, in turn, have shaped their own communities. Through their sites, people provide information about their lives, their families, their jobs, and their values. Moreover, they want to get in touch with other people who share similar interests—be it house renovation, rose gardens, macramé, or Mozart.

They Instill a Sense of Place with Codes of Behavior

Although occurring in virtual space, group members may well act as if the community is meeting in a physical public place with shared rules, values, and codes of behavior.9 The use of the real estate analogy for creating online communities, such as that pursued successfully by Geocities, clearly allows people not only to understand what is on offer but also to grasp the community’s norms and what is expected of them. The technology may be alien to some, but the concept has all the pull of comfortable familiarity.

Geocities sells its virtual real estate on this basis, offering more than 40 “neighborhoods.” Members who are science fiction and fantasy buffs might choose to “live” in Area51; golfers could choose Augusta; those who like art, poetry, prose, and the “Bohemian spirit,” could pick SoHo; and those who prize “hometown, family values” could choose Heartland.

Although online relationships are established between individual members rather than between Geocities and its members, Geocities has to create and maintain the appropriate atmosphere. It does so by encouraging people to become community leaders of virtual “townships” and “suburbs.” FortuneCity.com, which boasts a “population” of 3.1 million in its 20 themed districts, has district ministers who are “citizens of FortuneCity who offer themselves to be of service to the community.”

This may be fantasyland, but it obviously works! Tens of millions of people have joined a variety of Web communities (Parent Soup, Women’s Wire, Third Age, and Garden.com, among others). Their reasons for joining are both professional and social. According to a Business Week/Harris Poll in 1997, 42% of those involved in an online community said it was related to their profession, while 35% said their community was a social group, and 18% said they joined because of a hobby.10

They Promote Dialogues and Relationships

The threaded, asynchronous conversations that take place via many bulletin boards and newsgroups can be seen to replicate some features of face-to-face conversation, including immediacy, intimacy, and continuity. A study of an online group dedicated to discussing television soap operas11 shows that conversation flows casually and colloquially, just as it might in face-to-face contact. Through these discussions, people exchange information and viewpoints. Because they are not meeting face-to-face, however, trust has to be earned over time. The group determines people’s worth based on their ability to contribute and maintain conversations and relationships, on the interest generated in their contributions, and, ultimately, on the perceived validity of their insights. Status hierarchies can and do evolve over time.

They Encourage Active Participation by Everyone

Active participation is necessary to hold together an online community. It is generally believed that many, sometimes thousands of people, only read the messages posted on a bulletin board or a newsgroup, while relatively few people keep the dialogues and conversations active. Only those Web sites that allow for public consumer-to-consumer interaction are true online communities.

Internet commentator Esther Dyson12 is clear that virtual communities involve participation and reciprocation. In stating that a community “is a shared asset, created by the investment of its members,” she precludes Web site visitors from community definition. She contends that visitors, often referred to as lurkers since they observe but do not participate in any discussion, are like tourists who pass through: they look and perhaps admire, but they do not contribute to the lifeblood of the community. Active participation as an investment also denotes reciprocation (since not to be replied to or verbally recognized in the virtual world is the equivalent of being ignored as a nonperson). In this sense, online communities evolve as participants gradually recognize and get to know one another, develop ideas about who is credible and responsive, and over time begin to develop a sense of shared values and responsibilities.

If response is a requirement for existence in a virtual community, the fact that not everyone is accepted into an online community has powerful implications for a consumer brand community. Frequently, norms of online behavior have a minimum requirement of contributors to be “on topic.” In addition, they suggest that “many may speak, but few are heard.” In other words, people may post a message, but there might not be any response.

Other evidence states that many bulletin-board communities comprise but a “small coterie of habitués.” These findings suggest that some members may form into cliques within the greater community. The downside is that these individuals may also act as gatekeepers, deciding who is accepted into the community and who is ignored—in other words, which participants are allowed to exist.

Not all user groups are formed with altruistic notions. Some groups are born from opposition. For example, Team MacSuck was an online, anti-Macintosh computer group whose primary reason for existence was to prove “to MacLovers that the anti-Mac community is not a minority.”13 This was not so much a community of personal computer users as it was a loose community of some 1200 Mac haters, brought together “in the belief that Macintosh computers are worthless and the people who use them are snobs!”14

Management Issues for Brand-Based Online Communities

The now well-established virtual communities offer many useful lessons for those who wish to accrue benefits to a brand through an online community. They also hint at the difficulties inherent in creating and managing brand-based Web communities. Consumer product companies must address the issues of brand focus, community control, authenticity and ethics, community size and composition, and ultimately the objectives, management, and skills involved in running these community sites.

How Do You Attract Members to Your Online Community?

Any brand can want to develop an online community, but can every brand do it? Are all customers committed to a brand and desirous of having a brand relationship? Some brand products, like household cleaners, do not allow for much customer involvement. Other brands enjoy a natural focus by virtue of their high-involvement product offerings. Bosch, a manufacturer of power tools, hosts a forum for tradespeople and do-it-yourself enthusiasts to swap information and suggestions, including prices, which brand of power tool to buy, and how to fix cracks between walls and ceilings (see the tools forum on www.boschtools.com). The U.S. section of the Pentax site has a very active community of photography enthusiasts from around the world who exchange advice on buying special lenses, determining the best magazine to buy, fixing troublesome features, photographing butterflies, and so forth (www.pentax.com/discussion.html).

Other large consumer companies have built popular communities around associated interests. On its family.com site, Disney operates one of the liveliest bulletin boards targeted at mothers. Its discussion topics deal with parenting, marriage, health, food, education, holidays, and many other issues. Canada’s Molson beer attracts ice-hockey enthusiasts to its site with information about the sport and message boards so fans can exchange views and gossip about their teams and ice-hockey heroes (www.molson.com.) CNN hosts many discussion boards and chat sites, generated in part from viewers of its news broadcasts and in part from its regular audience that seeks out CNN when traveling. Not surprisingly, CNN has an active community of business travelers who share tips about packing, rate worldwide restaurants, and debate the hand-luggage policies of various airlines (community.cnn.com). The key is finding a related issue that captures people’s attention. People must care about the issue, have opinions about it, and be enthusiastic enough to share their views.

Advantages may well accrue to the first movers in these cases. After all, there are only so many parenting or hobby-related sites that any one consumer will belong to. Johnson & Johnson is about to launch Mothers’ Circle, a discussion group for mothers to exchange ideas, suggestions, and advice on its Your Baby site (www.yourbaby.com). Johnson & Johnson will be in competition for the attention of mothers with the many well-established, fully developed, and similarly focused communities to be found, such as iParenting.com (which has more than 200 active discussion boards), parents.com, parentsoup.com, or parenttime.com. Pets Unleashed, which attracts pet owners to the Heinz pet foods site (www.heinzpet.com), is soon to launch an Owners’ Corner where pet owners can contact each other. Meanwhile, its rival Purina has partnered up with the busy and well-established Pet Place at the iVillage community site (www.ivillage.com/pets).

Running a successful Web site filled with games, movie clips, and creative graphics is not the same thing as running a brand community. The site must offer members not only entertainment but also a sense of involvement and even ownership. Communities require a truly bottom-up view of brand building, whereby the customers create the content, and are, in a sense, responsible for it. This view contrasts markedly with many brand strategists’ traditional top-down view of business, where products and services are created by organizations and sold to customers.

How Many Members Do You Want, and How Active Should They Be?

Additional questions concern the size and composition of the brand-based community. Web community commentators have noted that the larger the community, the more likely it is to lose an essential intimacy. Good communities have “fractal depth”15—that is, they are capable of being segmented into subcommunities centered on specific topics of interest (user groups refer to these as special interest groups). The “higher order issue,” which will be the key attraction of the brand community site, must be capable of hosting many related interests and strong enough to give coherence and overall added value to each specific interest group.

We have already noted that thousands of people lurk, while only tens or hundreds participate. So how do we define this community? Do we include the silent visitors? How do we treat the shy habitués, as distinct from tourists? How representative of the entire community will be the few enthusiasts who keep the community alive? What are the brand community objectives? To attract more visitors? To have more active participants? These issues are of particular importance when hundreds of millions of consumers are buying the brand items, but only hundreds participate in a brand-based online community.

Should There Be Links to Other Sites?

Should the brand create content exclusively about itself? Or should the site contain links to other brand community sites? Related but noncompetitive sites would be harmless, such as a travel agency offering links to country sites or city sites. Indeed, links could be made to competitors’ sites, depending on how general was the point of interest. A brand could establish a community around a sport and add links if the community expressed an interest in accessing a particular sporting event, like the international motor-bike Grand Prix or the Tour de France for cycling. Although the ability to access competitors’ sites—and therefore competitors’ products—could be interesting to the community, is it in the brand’s interest to provide access to competitors?

How Much Control Should the Brand Owner Exert over Content?

The origins of the Internet are noncommercial and, in a sense, democratic. The Internet developed as a user-controlled medium, and the success of community brands like Geocities suggests that users are still in control. In the consumer brand-based online community, it is likely the consumer will want to control the relationship. When building communities, marketers will have to treat their target market accordingly. To provide the best experience, brand sites will have to make consumers feel more like community members or partners and encourage them to initiate multilateral relationships.

By overly controlling the discussion or dialogue with in communities, brand sites face the risks of losing the interest of their members and losing the rich creativity inherent in their audience. Decisions about how much control a brand host should exercise over its online community will reflect, or may ultimately influence, the brand’s personality. For example, should the host adopt a strict controlling demeanor, or should it tolerate a less regulated yet potentially rebellious outlook?

The balance between freedom of speech and editori al or community control is apparent in online communities where the participants generate the content eBay, the popular online auction house, which styles itself first and foremost as a community and second as a venue for online commercial transaction, is witness to the pains and pleasures of membership self-policing. Its individual buyers and sellers judge the decency of their transaction partners on public feedback forums. So important are these judgments that reputations may hold as much value as the goods that are traded. An article in the Washington Post details how one member was expelled from the community (“vaporized”) for what the company considered her overly aggressive pursuit of dishonest participants.16 The article also mentions that another collector misplaced an item to be sold because he was in the midst of a family crisis. Although the collector explained his situation, the buyer gave him a negative rating. The collector still feels bad about the feedback

eBay executives are aware that a system of community policing does have its limits. They are now cracking down on “feedback abuse,” whereby some participants have tried to inflate their reputations with positive feedback sent by friends, while others have been known to “feedback bomb” their adversaries with negative messages.

If consumer-goods brand owners are to use their online communities as a “reality check” on the success (or otherwise) of their activities, they will have to develop a tolerance for the excesses and opinions of their participants. Finding the line to draw will not be easy. For example, should they tolerate the appearance of negative comments about the brand host or comparisons with competitors’ products on their sites?

Monsanto, the food and biotechnology company, retains a strong element of control over its discussion forums on its U.K. Web site (monsanto.co.uk). The firm provides specific questions for discussion, and comments submitted by anonymous contributors are not accepted. Shell International Petroleum, on the other hand, apart from eliminating obscenities, takes a completely uncensored approach to its online discussions. Its U.S. forum (www.shell.com) takes a bold step and allows highly critical comments from both individuals and lobbying groups. This is a very active site; it attracts comments from Shell employees as well as Shell customers.

America Online has also experienced the difficulties of moderating online discussions in its many bulletin boards. The widely reported moratorium on its Irish heritage discussion for a 17-day cooling-off period brought forth accusations of it behaving like the “thought police.” AOL prefers its communities to monitor themselves and trains its volunteer monitors to be “agnostic about the specific content and to look more at things like tone.” The company admits that there is a delicate balance between maintaining a sense of community without violating the principles of free speech.17 Given AOL’s business and way of generating revenues, its investment in community training and policing is easy to justify. It is, however, a “brave new world” for those hitherto charged with marketing brands of diapers or disposable razors.

The policy on control is a tricky one to gauge. If the online brand community were to develop a sense of injustice and pit itself against the “management,” then the brand owners would have an ugly situation on their hands. Not to allow negative comments, however, might create a sterile environment that would drive away participation and only encourage the emergence of “unofficial sites.”

The appropriate response to unofficial and hate sites is a vexing issue. As already noted, hate sites do attract visitors, although it is rare for whole communities to coalesce around them. More often they are peopled with curious visitors who then move on. Wal-Mart, Toys ‘R Us, Nike, United Airlines, and many others have been victim to hate sites set up by disgruntled employees or customers.18

Litigation appears to be a final resort but is rarely pursued since international legislation makes this an extremely complex route. Prevention seems to be the better way. Some companies have bought the relevant Web addresses (URLs) that include “sucks.com” suffixes and “Ihate” prefixes. Perhaps the most effective approach is to neutralize the hate comments with user-initiated counterarguments, as Macintosh users did on the Team MacSucks site, or to allow well-argued criticisms to be voiced and counterargued by community members as Shell does.

How Does Anonymity Affect Your Online Community Site?

It is widely understood among marketers (but possibly not among the general public) that some brands use moderators at their sites whose actual role and relationship to the corporation is deliberately hidden from the other participants; that is, they pose as ordinary consumers. The ethics of such a practice are, of course, open to debate.

One of the key contradictions of the medium is that for all its potential as a means of communication for social networking, socializing via the Internet can be anonymous. People can and do hide their real personalities and invent new ones for themselves.19 Impression management scholars might argue that whether on the Web or not, we are always deliberately hiding some things and revealing others about ourselves and are thus always presenting multiple personae to cope with the variety of roles we play in everyday life. However, there is something about the facelessness of the interaction that may both attract some, while simultaneously repelling others, among a brand’s consumers.

Brand owners may want to exercise some level of control, for example, to prevent the formation of a clique that is hostile to newcomers. The facelessness of participation certainly facilitates interventions in a community, allowing it to seem as if messages were sent by legitimate members of the brand community (i.e., regular consumers rather than the brand employee). Clearly, there are issues of both brand-community authenticity as well as ethics to be considered here.

In one sense, these issues are being faced by brands that have pseudo-personalities (i.e., named people) fronting hotlines or inquiry desks. Nor are these issues too dissimilar to the perception that many “letters to the editors” are invented by the publication in question. We might equally question the practice of placing brand products in motion pictures or in real life, witness Daewoo’s practice of giving cars to college students.20 Brand owners may see their anonymous intervention in bulletin boards and community sites as no more illegitimate than providing journalists with opportunities to experience their products or with stories to write up into articles.

However, given that the brand will ultimately be judged on the quality of the experience it offers through its community, these issues cannot be sidestepped by the brand’s owners. Decisions and policies need to be made at the highest organizational levels. If the brand lives by the quality and integrity of the ingredients in its product or service offering, it must have equally high standards in its interactions with its virtual community members.

New Skills Needed to Manage Online Communities

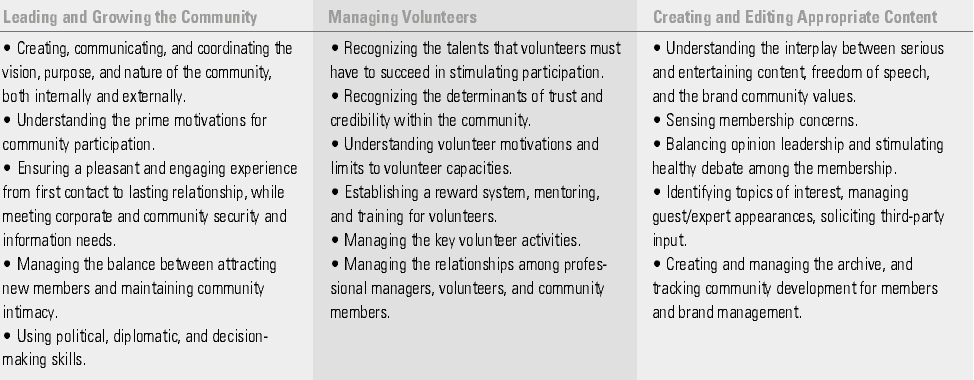

Exercising the delicate balance between controlling and letting go will require a new set of skills within the brand organization. The community must not be overly proscribed in what it says or does, yet it should cohere with the brand values as they are intended. Brand-community management brings together three skill sets that exist separately in the nondigital world but are rarely sought after by traditional marketing management. These are the skills associated with community leadership and development, with supervision of volunteer managers, and with editorial expertise. In the electronic world of community brand management, these skills must coalesce either within the same person or at least within the community brand-management team.

Community Leadership and Development

Community leaders must have the necessary skills to create a purposeful and attractive community vision, to attract and shepherd new members, to stimulate member involvement and participation, and to nurture the community spirit and keep it refreshed and relevant to members’ needs over time. These skills are more readily associated with people who spend their time working in more traditional communities—for example, in leaders of religious groups, community help groups, parent-teacher organizations, and the user groups discussed earlier.

Using the model of the religious community provides insight into the practices that accompany these skills. For centuries, religious leaders have acknowledged the importance of marking the passage of time and observing the cyclical rhythm of nature. Commentators involved with online communities have observed how equally important it is to mark such events in virtual communities.21 Again, as with religious communities, special celebratory events are interspersed with frequent and regular communion, so that routines of participation are established. Similarly, an established calendar of events enables community participants to schedule their participation ahead of time. For example, Disney’s Family.com site marks the passage of seasons by encouraging mothers to exchange ideas about keeping the children amused during vacations, costumes for Halloween parties, or new dishes or recipes to prepare for Thanksgiving.Parenthoodweb (www.parenthoodweb.com) organizes clubs for expectant mothers based on the month in which their baby is due.

Managing Volunteers

Volunteers serve at many community Web sites, providing a means of:

- keeping community management close to its roots (i.e., the membership base),

- keeping the costs of managing thousands of individualized and personalized relationships within sensible limits, and

- recognizing and rewarding the desires and abilities of many deeply committed community members to increase their involvement with the community and the brand.

Volunteers function as chat-room hosts and discussion moderators and as editors (often referred to as “sysops”) for specific bulletin boards, where they delete unsuitable material or repetitive questions and answers. By 1997, some 40,000 sysops were online in the United States.22 America Online (AOL) enlists the help of more than 10,000 volunteers to patrol its bulletin boards and employs approximately 100 subscribers (known as the Community Action Team) to determine when comments are unacceptable.23

Motivating, rewarding, and leading volunteers presents a set of challenges familiar to professionals who manage user groups, charities, or local community groups. The key to trouble-free operation lies in managing the tensions that inevitably arise when paid, full-time professionals interact with unpaid, part-time volunteers. The potential for conflict lies in unclear goals, feelings of exploitation, and an inability to detect when either group is treading on the other’s toes (intentionally or not). Appropriate objectives, structures, training, open channels of communication, frequent contact, systems for arbitration, and early detection of overloads are essential for the smooth operation of the volunteer-professional interface. Volunteers’ perceptions of overload are usually manifested in cries of exploitation. In a lawsuit filed against AOL, two volunteers allege that the company should have compensated them for their work (currently, AOL rewards volunteers with a free account).24

Tools are available to help volunteers handle everyday tasks. For example, Artificial Life has created smart “bots” (short for robot, an intelligent software tool that “lives” and interacts in a humanlike manner with the user). These bots respond to naturally phrased questioning and can be customized to adopt a distinctive personality.25 Bots can be used to take over routine meeting and greeting activities or answer FAQs (frequently asked questions). “Chatterbots” specialize in small talk and can develop a memory and recognition system to enhance interchange with potentially thousands of returning visitors.

Editorial Expertise

Community members interact primarily through their own text-based content. Just as in the nondigital world, content generates content. To attract people into the Web site and then entice people to participate, the community editor-in-chief will have to develop new sources of content. To keep the audience’s interest, the editor must be able to create or acquire articles from internal or external resources, to choose appropriate reference material, to compile directories, and to archive material on the Web site.

The editorial task is also one of ensuring that the brand personality is portrayed consistently and communicated correctly through the site design. Recent data from an extensive program at Stanford University shows that all interaction with computers is rich in its ability to convey personality, because users essentially treat computers as social actors.26 Moreover, users anthropomorphize the machines and perceive personalities through the content and form of the messages built into software programs—even through simple error messages.27 While we treat many technologies and all media in this way, the Internet allows for interaction with the personalities expressed. Computer-derived personalities will be deduced, interactively or otherwise, whether they are intended or not.

These three skill sets—leadership, managing volunteers, and editorial skills—will help the volunteer and professional managers as they undertake their new activities and responsibilities in the brand-based online community.

In addition to these skills, constant communication between the membership and its volunteer leaders, and between the volunteer managers and the professional managers, is necessary to make these communities work. Brand-community managers must also communicate with the professionals concerned with all other aspects of the brand—that is, those in traditional media communication, sales, operations, and new business development.

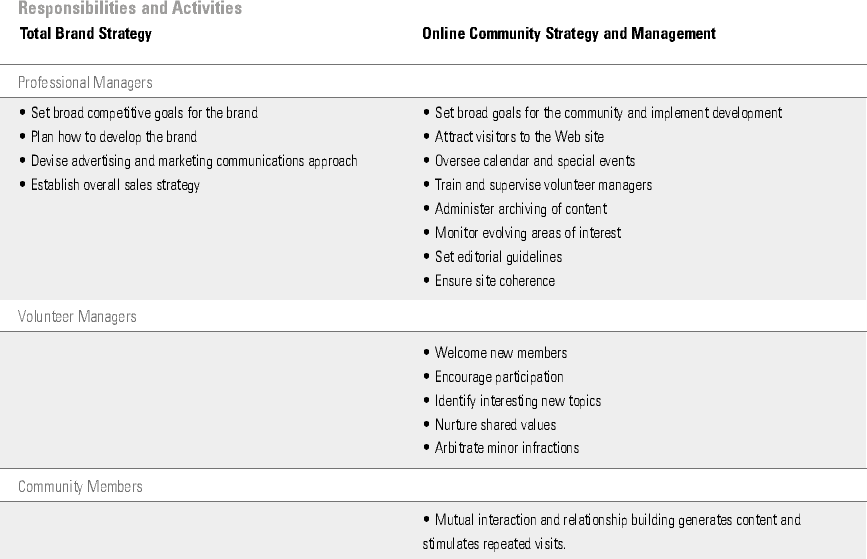

The Ultimate Skill: Linking Community Strategy to the Total Brand Strategy

Ultimately, a company’s brand-based Web community strategy must be part of its total brand strategy. The various communication vehicles used by brand managers are widely acknowledged to work better when they are in harmony, either by providing the same core message to different audiences or different expressions of the same message. The integration strategy determines how the various aspects of the brand can be made to cohere and benefit the total brand. The integration skills required of brand-community managers are not new to brand management but are perhaps some of the most important.

Companies capable of multifunctional communication and integration will achieve the maximum early benefit from a brand community. However, keep in mind that once given a voice, the brand community will act as the living manifestation of the brand’s personality and relationship with consumers. The obligations inherent in a brand relationship, now vocalized by the online community participants, will have to be fulfilled.

References

1. See: www.forumone.com.

2. N. Watson, “Why We Argue About Virtual Community: A Case Study of the Phish.Net Fan Community,” in Virtual Culture S. Jones, ed. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1997), pp. 102–132.

3. For examples of consumer cynicism about relationship attempts on behalf of consumer services companies, see:

S. Fournier, S. Dobscha, and D.G. Mick, “Preventing the Premature Death of Relationship Marketing,” Harvard Business Review, volume 76, January–February 1998, pp. 43–51.

4. See research based on the Market Research Corporation of America quoted in: G. Hallberg, All Consumers Are Not Created Equal New York: John Wiley, 1995). For similar European studies, see:

M. Uncles, K. Hammond, A.S.C. Ehrenberg, and R.E. Davies, “A Replication Study of Two Brand Loyalty Measures,” European Journal of Operational Research, volume 76, 1994, pp. 375–384.

5. A.S.C. Ehrenberg and M. Uncles, “Understanding Dirichlet-Type Markets” (London, South Bank University and Sydney, University of New South Wales, working paper, 1999).

6. S. Munger, “Leveraging New Technology To Build Brand Loyalty,” Direct Marketing, volume 59, December 1996, pp. 58–60.

7. T. Duncan and S. Moriarty, Driving Brand Value: Using Integrated Marketing to Manage Profitable Stakeholder Relationships (New York: McGraw Hill, 1997).

8. R. Hurst, Net Profit, May 1998, p. 11.

9. For an extensive discussion of online codes of behavior, see:

M. McLaughlin, K. Osborne, and C. Smith, “Standards of Conduct on Usenet,” in Cybersociety, S. Jones, ed. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1995), pp. 90–111.

10. “Internet Communities,” Business Week, 5 May 1997, pp. 64.

11. C.L. Harrington and D.D. Bielby, “Where Did You Hear That? Technology and the Social Organization of Gossip,” Sociological Quarterly, volume 36, number 3, 1995, pp. 607–628.

12. E. Dyson, Release 2.1: A Design for Living in the Digital Age (Broadway Books, 1998).

13. A. Muniz, Jr. and T.C. O’Guinn, “Brand Community,” unpublished manuscript, August 1999 (contact oguinn@mail.duke.edu).

14. Quote from the Team MacSuck Yahoo listing, February 1999.

15. J. Hagel and A.G. Armstrong, Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Communities (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997).

16. M. Leibovich, “eBay, Cyburbia’s New Subdivision, Stokes a Boom with an Emphasis on Community,” Washington Post, 31 January 1999, section A, p. 1.

17. A. Harmon, “Worries about Big Brother at America Online” New York Times, 31 January 1999, p. 1.

18. “A Site for Sore Heads,” Business Week, 12 April 1999, p. 86.

19. For a discussion on people adopting multiple personae in Web communities, see:

R.C. MacKinnon, “Searching for the Leviathan in Usenet,” in Cybersociety, S. Jones, ed. (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1995), pp. 112–137.

20. L. Armstrong, “Daewoo: Big Car on Campus?” Business Week, 31 August 1998, p. 32.

21. See, for example, the advice given by: Dyson (1998); and

K. Shelton and T. McNeeley, Virtual Communities Companion (Scottsdale, Arizona: Coriolos Group, 1997).

22. J. Hagel and A.G. Armstrong, Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Communities (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997).

23. Harmon (1999).

24. “Former Volunteers Sue AOL, Seeking Back Pay for Work,” New York Times, 26 May 1999, p. 10.

25. For an example, see:

the bots on www.artificial-life.com.

26. B. Reeves and C. Nass, The Media Equation (Stanford, California: CSLI Publications, Center for the Study of Language and Information, 1996).

27. Ibid.