Increasing Supplier-Driven Innovation

When customers collaborate with suppliers they can build trust, reduce relational stress, and increase innovation-related activities.

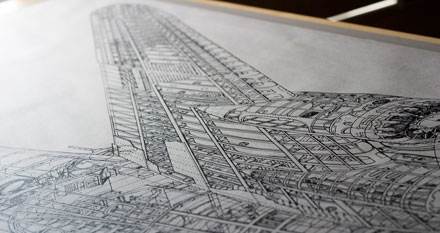

Image courtesy of Flickr user ChrisBlakeley.

More than 50 years ago, management guru Peter Drucker identified innovation as one of the basic ways in which a business builds and maintains a competitive position in the marketplace.1 It wasn’t until recently, however, that companies not only established internal environments conducive to innovation but also began identifying, cultivating and taking advantage of a wide variety of external sources for innovation.2

The Leading Question

How can a customer collaborate with a supplier more, while competing with it less, to increase the supplier’s innovation-related activities?

Findings

How can supply chains be designed and managed not only for reduced cost but also for multiple outcomes?

- Involve the supplier in the customer’s processes, especially product development.

- Demonstrate openness and share information with the supplier in a timely manner.

- Work with the supplier to help it improve its competitiveness, both in cost and quality.

Among such sources, suppliers are recognized as having especially large innovation potential because they know what the companies — that is, their customers — are doing and need and also because mechanisms for knowledge transfer from supplier to customer are typically in place.3 But years of evaluating supplier working relations in various manufacturing and service industries reveal that it is one thing for a mechanism to be available by which suppliers may transfer innovation to customers and quite another for the suppliers actually to do the transferring.

Competitive Side Of Collaboration

Customer/supplier activities that are collaborative tend to build trust and subsequently foster supplier innovation transfer. There are, however, competitive activities in every customer/supplier relationship that result in distrust, which negatively affects such transfers. For example, a company and its supplier may diligently and unselfishly work together to provide the highest-quality end product, thereby strengthening their mutual trust. But when the company asks the same supplier for price reductions, both parties will compete to steer the negotiation to their own advantage, and stress will be created in their working relations. It is this relational stress and its accompanying distrust that cause suppliers to limit the extent to which they will transfer innovations to the customer.