Managing the Human Cloud

Companies have increasing opportunities to tap into a virtual, on-demand workforce. But the organizational challenges of this latest wave of outsourcing require new management models and skills.

Topics

Online retailer Zappos, which is led by CEO Tony Hsieh, has used aggregator MTurk to perform some “human intelligence” tasks.

Image courtesy of Flickr user Robert Scoble.

Chase Rief runs a small media company in Newport Beach, California — or, rather, from Newport Beach: Rief Media’s 14-person workforce is scattered around the world, all independent contractors he hired through an online service called oDesk. At the other end of the size spectrum, life insurance giant Aegon has an on-demand workforce of 300 licensed virtual agents managed through another online intermediary, LiveOps. They are not Aegon employees but are scheduled for inbound and outbound calling through LiveOps’ routing software.

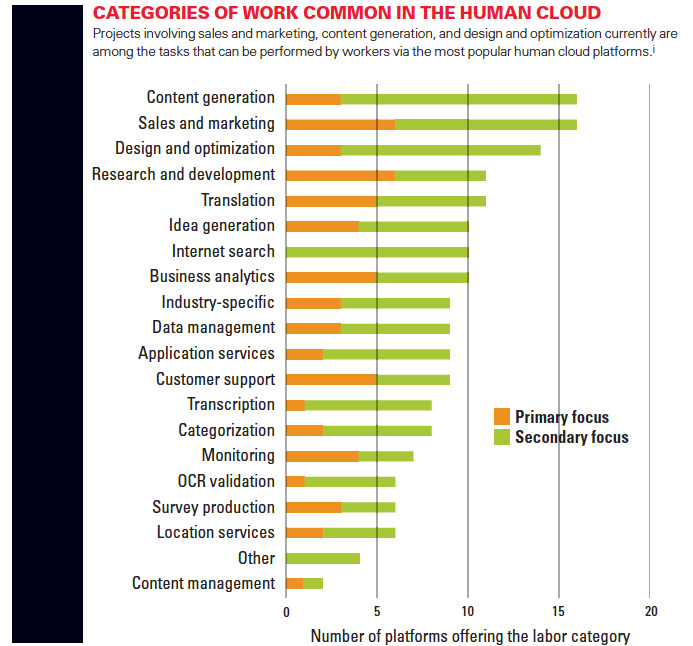

First came outsourcing of IT and business processes. Next came offshore outsourcing. Now comes the human cloud. A third-generation sourcing ecosystem already being used by companies as diverse as Rief Media and Aegon, the human cloud is centered on an online middleman that engages a pool of virtual workers that can be tapped on demand to provide a wide range of services to any interested buyer. Although jobs involving content generation, sales and marketing, and design and optimization currently top the list of tasks that can be performed by cloud workers, a recent industry report identifies at least 15 major labor categories that could be sent to the human cloud.1 (See “Categories of Work Common in the Human Cloud.”)

The human cloud is growing rapidly. Year-over-year growth in the global revenue of human cloud platforms was 53% for 2010 and 74% for 2011. The number of platforms and middlemen has also skyrocketed. Using a narrow definition, we counted more than 100 active platforms in 2012, up from perhaps 40 in 2011.

Some analysts see the human cloud as potentially more disruptive than the previous two sourcing waves. They believe it will reshape established business processes, redraw organizational boundaries and — most importantly — profoundly change global labor markets. After studying the evolution of human cloud platforms over the last few years, we share these analysts’ excitement but also think that the road ahead will be bumpier than some advocates would have us believe. (See “About the Research.”) As with the past waves of outsourcing, harnessing the power of the human cloud will require the evolution and adoption of a new set of best practices and structures by the key sourcing stakeholders — the buyers and the suppliers.

The Origins of the Human Cloud

The Leading Question

How is the human cloud changing outsourcing?

Findings

- Companies can engage a pool of online workers as needed.

- The major human cloud platforms have developed four business models.

- Perceived risk and limited capacity to handle large scale projects are two major obstacles being overcome.

The human cloud is not a new idea. At least two interrelated phenomena have followed this line of thinking in the past: crowdsourcing and microsourcing.2

Crowdsourcing allows organizations to transfer a task previously performed in-house to a large, usually undefined, group of people.3 Wikipedia, iStockphoto and other high-profile examples demonstrated the power of crowdsourcing in enabling new business models. Crowdsourcing has also proved valuable for traditional organizations. The U.S. space agency NASA, for example, developed a successful initiative — NASA Clickworkers — that enlisted volunteers from all over the world to help identify and label landforms on Mars. In general, crowdsourcing involves large-scale projects completed by a collective of people with no direct or guaranteed monetary incentive to participate.

Microsourcing allows buyers to source paid projects, or fractional tasks, over the Internet from individuals or small providers. The initial idea centered on an online marketplace for freelancers, similar to eBay, but in which buyers and suppliers exchange services instead of goods. Microsourcing relies on a one-to-one relationship between a single buyer and supplier and involves jobs with limited scope and scale. Yet microsourcing is similar to crowdsourcing in that the initial search for a supplier starts with an open call aimed at a large and mostly undefined collective of potential workers.

However, despite enthusiasm for the concept of a virtual workforce, two obstacles have prevented businesses from large-scale adoption of crowdsourcing and microsourcing since their first introduction more than 12 years ago: perceived risk, and limited capacity to handle projects of larger scale and scope.

Most managers feel anxious about delegating work to a supplier with whom they have had only virtual contact. Engaging an online crowd requires “a leap of faith,” as one executive buyer told us. In her organization, she has had to work hard to convince colleagues to start working with suppliers they can neither shake hands with nor train. “I get lots of pushback when I propose crowdsourcing,” she says. Not surprisingly, many organizations only crowdsource projects that are low-budget and have no hard deadline.

The more serious problem has been the limited capacity of crowdsourcing and microsourcing to handle complex and large-scale work. Microsourcing, for instance, relies on dyadic relationships consisting of one buyer, one supplier and a well-defined final deliverable. Microsourcing platforms provide easy and efficient mechanisms to connect the two parties but offer limited support for collaboration and coordination. This makes them great for facilitating limited short-term projects that can be completed by a single supplier but not for the more common need for multiple interconnected tasks that demand the coordination of multiple skill sets, or for engagement-based services such as support, help desk and infrastructure maintenance.

The Evolution of the Human Cloud

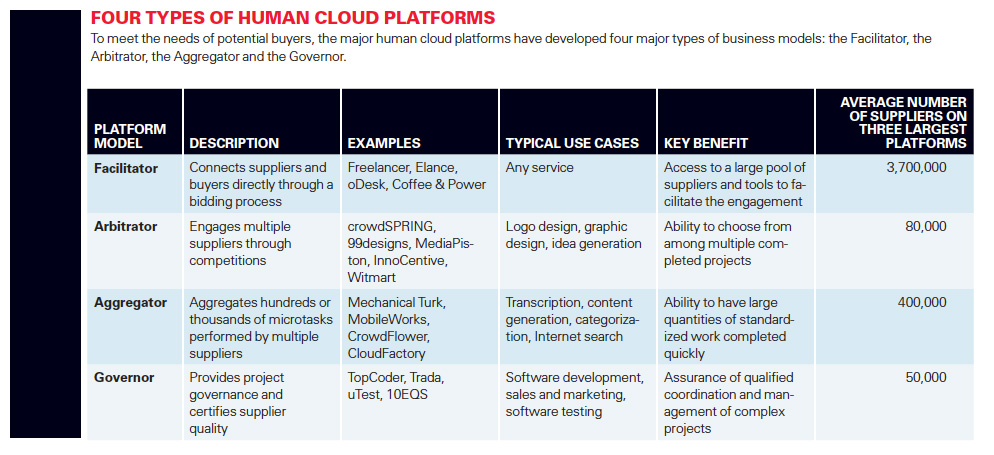

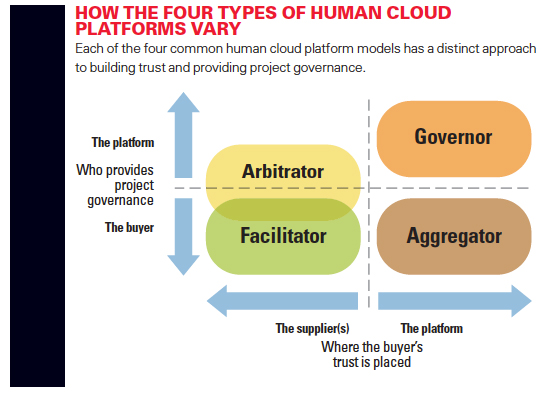

To meet the needs of more potential buyers, the major human cloud platforms have developed four business models that show great promise in overcoming these obstacles and spurring growth. (See “Four Types of Human Cloud Platforms.”)

The Facilitator Model: Supplier Transparency The Facilitator model is a direct successor to microsourcing. To reduce perceived risks to buyers, these platforms have added features that reduce supplier anonymity. Buyers may still not be able to look the supplier in the eye, but they do have access to a wealth of information about the candidate. Facilitator platforms, like Elance and oDesk, have built frameworks for suppliers to share their professional and personal backgrounds, show off their portfolios and earnings history and demonstrate skills through standardized tests. Buyers now can also interview suppliers before deciding whether to hire them.

The platforms have also made workflows more transparent to the buyer. Elance, for example, offers project management tools that enable buyers to create project milestones, receive status reports from suppliers and link payments to milestone completion. Similarly, oDesk has developed a sophisticated system of remote work management that monitors suppliers’ online work activity and tracks time spent on each task. Virtual dashboards enable buyers to manage teams of suppliers to take on more complex jobs and projects. Such features give companies such as tiny Rief Media the confidence and ability to manage a virtual workforce.

The Arbitrator Model: Supplier Redundancy Companies often have to source work that is highly unstructured and difficult to evaluate and/or that requires special expertise, such as design or research and development. The project’s outcome is often uncertain, and quality is best evaluated against other alternatives. Tapping into the global talent pool and engaging multiple skilled providers to work on the same project would be highly attractive but, before the human cloud, was beyond reach of all but the largest companies.

A human cloud model we call the Arbitrator model aims to make this option more accessible. It provides buyers with on-demand access to a specialized community of skilled suppliers who can be engaged on a project via a competition or contest. The buyer can choose from multiple competing inputs/deliverables and pay only for the one it finds most valuable. This outcome-driven selection also significantly reduces perceived risks for the buyer.

One leading Arbitrator, crowdSPRING, connects buyers with a global community of creative designers. Having started out with logo design, crowdSPRING today runs a wide range of projects, including copywriting and website and industrial design. South Korean-based electronics giant LG Electronics, for example, turned to crowdSPRING to carry out a global online competition to design a mobile phone of the future. In its 2010 competition, more than 400 designs were submitted for consideration by the internal LG panel of judges. Another example of the Arbitrator model is Massachusetts-based InnoCentive, which uses crowdsourcing to solve complex problems. InnoCentive’s online community includes scientists and researchers ready to take on unsolved R&D problems for companies throughout the world.

The Aggregator Model: Task Aggregation Some companies have work that does not require coordination among the workers who perform a very large number of simple, repetitive tasks, such as cleaning up a large customer contacts database. An Aggregator provides buyers with a single interface to send work to a large number of small suppliers. It provides an infrastructure to run projects similar to that of NASA Clickworkers at minimal cost and ramp-up time.

Consider, for example, Amazon Mechanical Turk, or MTurk, which in 2011 boasted over 500,000 suppliers. Buyers post projects consisting of a large number of simple repetitive tasks that workers are willing to perform for a few cents. These tasks, which MTurk calls “human intelligence tasks,” do not require any special expertise or knowledge on the part of suppliers, but they do involve human judgment and are difficult to automate. Typical MTurk projects include translation, audio and video transcription, categorization and tagging, as well as data entry and product or contact search. Zappos, an online retailer, has used MTurk to correct spelling and grammar on customer reviews since 2009. Another aggregator, Finland-based Microtask, segments projects and then breaks them down into game-like tasks that offer players or workers monetary and nonmonetary incentives for completion and quality.

Recently, Aggregators have begun to provide governance services, such as microtask definition and quality control. Germany-based Clickworker, for instance, guarantees quality to the buyer by having more experienced workers review tasks completed by their less experienced counterparts. This approach appeals to larger buyers. Honda, for example, employed Clickworker to complete a project involving tagging objects in images of traffic situations. The output was used by the automaker to develop an onboard computer functionality to help vehicles avoid road obstacles.

The Governor Model: Project Governance Perhaps the mightiest challenge of the human cloud lies in taking on more complex projects. Indeed, the various human cloud platforms recognize that they need scale. According to a 2012 industry report, their No. 1 strategic focus is to “win more large enterprise clients.”4 To tackle this, platforms in the Governor model employ a combination of human project managers working on-staff and a sophisticated software-enabled framework for monitoring and coordinating individual tasks. Governors provide a thicker layer of project governance, including collecting project requirements from the client, breaking them up into microtasks, coordinating completion and sequencing of individual tasks, conducting supplier certification and ensuring quality of the final deliverable.

Computer programming service company TopCoder and its community-based model of software development provide perhaps the most advanced example of a Governor platform. The model relies on breaking down traditional steps of a software development project, such as conceptualization, requirements specification, architecture design, component production, assembly, certification and deployment, into a series of online competitions, which are then structured as a “game plan.” Multiple suppliers take part in each of the competitions, and the winning output of each preceding round (as determined by more experienced members of the community) becomes an input to the subsequent one. Atomization allows for deeper coder specialization, leading to better quality. A TopCoder employee — the platform manager — often coordinates completion of the game plan and serves as a liaison between the community and the buyer. Using this model, TopCoder has built and deployed enterprise-grade software for multinationals such as financial giant UBS, home loan company Lending Tree, and sports broadcaster ESPN.

To reduce perceived risks to the buyer, the Aggregator and Governor models shift the focus from individual suppliers (the crowd) to the platform (the company). (See “How the Four Types of Human Cloud Platforms Vary.”) The platform becomes the primary point of contact for the buyer and assumes responsibility for project-related risks. This arrangement requires a much smaller leap of faith on the part of the buyer, since it resembles a traditional outsourcing relationship.

Managing Human Cloud Initiatives

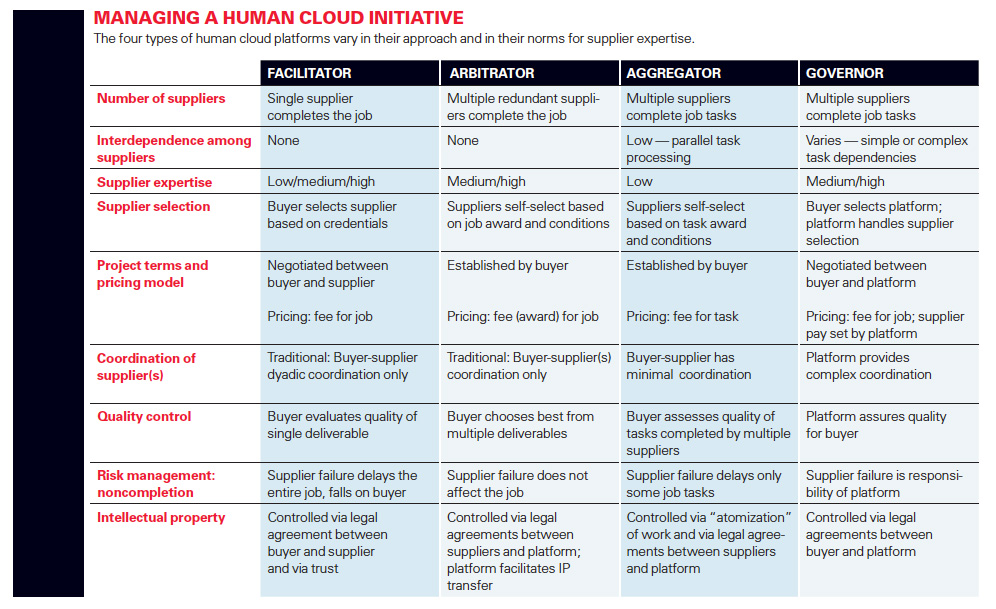

Of course, the buyer also needs to make adjustments to make the human cloud useful. (See “Managing a Human Cloud Initiative.”) Because human cloud projects are really just a special flavor of outsourcing, buyers may find it helpful to think about launching and managing a human cloud initiative in the same way that they manage the main phases of any outsourcing engagement.5

Architectural phase Architectural design is the first phase of sourcing, the point at which a buyer defines its choices on key dimensions of the future engagement. In the human cloud context, three such dimensions need to be taken into account: the number of suppliers, the degree of interdependence among suppliers and supplier expertise.

Three of the platform models are based on multiple suppliers (these are the embodiment of the crowd), while the Facilitator model depends on just one supplier for project scope. The latter is the traditional business model: one buyer, one supplier. A small business that develops its storefront website by contracting through the virtual employment agency vWorker is an example of such a scenario. Given that the buyer can specify the storefront’s functional and technological requirements, its implementation is usually fairly straightforward.

Where the human cloud introduces real innovation is in providing multiple redundant suppliers at once, sometimes via a competition or contest-based mechanism. This approach, embodied in the Arbitrator model, is suited for jobs where the quality of the final deliverable is difficult to assure. Redundancy in this context increases the probability that the buyer will obtain a desired outcome. For example, multiple InnoCentive Solvers (working sometimes in teams) who take on a tricky research problem are more likely to come up with an acceptable solution than a single research team.

The Governor model is the most powerful in its handling of multiple suppliers. This model tends to involve projects that comprise of diverse tasks with complex interdependencies among them and that require significant coordination of suppliers. TopCoder’s approach of developing and deploying enterprise software, such as an underwriting solution for a major U.S. insurer, is a good example. Because of the greater complexity and scope of the project, suppliers on Governor platforms also tend to have a higher level of expertise and possess a wider range of skill sets. LiveOps, for example, boasts a pool of trained and certified at-home call agents capable of handling customer acquisition, customer service, fundraising and disaster recovery tasks for corporate buyers across a variety of industries.

The four types of human cloud platforms vary in their norms for supplier expertise and accommodate a wide range of jobs, from simple tasks, such as data entry or naming contests, to those requiring significant professional training and experience, such as Web development and industrial design. The Aggregator model, typified by MTurk and MobileWorks, often requires no special supplier expertise whatsoever.

Engagement phase Engagement is the sourcing phase in which the buyer chooses one or more suppliers to carry out the work and establishes the contract terms. In recruiting suppliers, the buyer needs to consider who is responsible for the selection process and what criteria the selection is based on.

The Facilitator model offers the most traditional sourcing approach, with suppliers submitting bids and buyers doing due diligence. On Elance, for example, buyers choose suppliers by evaluating project proposals; reviewing online resumes, portfolios and standardized skill test scores; studying feedback from prior engagements; and in some cases conducting online interviews.

The Governor model is similar, but here the buyer chooses the platform rather than the supplier. The platform then handles all aspects of supplier selection. In both Facilitator and Governor scenarios, careful attention to verifying the counterparty capabilities is crucial, as, once chosen, the supplier or the platform assumes responsibility for the job.

Two human cloud models that deviate drastically from traditional outsourcing in the Engagement phase are the Arbitrator and Aggregator models. These models typically allow suppliers to self-select work on a posted project. Suppliers are tempted to join if the award promised matches the perceived effort involved. For example, the “grand challenges” on InnoCentive — highly complex scientific problems requiring top-level expertise — can carry awards in excess of $1 million, whereas a simple “human intelligence task” on Amazon MTurk, such as data entry, may pay 10 cents.

Additionally, nonfinancial factors, such as reputation or learning, may come into play. The creative designers at crowdSPRING seek projects where there are opportunities for learning; hence, they often prefer to join “open” projects, where the buyer’s feedback on submitted designs is visible to everybody, rather than “pro” projects, where all communication between the buyer and the creative is kept confidential.

Operational phase With suppliers lined up and terms negotiated, the buyer shifts its focus to executing the sourcing initiative. Traditional dyadic buyer-supplier coordination in the Facilitator and Arbitrator models requires the buyer to be prepared to maintain close, ongoing interactions with the supplier or suppliers in order to provide feedback and oversight. As an executive with vWorker pointed out: “Sometimes buyers think they can just say, ‘Here is what I want,’ and then come back later and see it created. That never works. Unless the parties are to commit the time for interaction and communication, the result is not going to be good and buyers are not going to be happy.”

The Aggregator model, with its focus on parallel microtask processing, requires less ongoing coordination. Consider, for example, collecting categorized product instances from workers on Amazon MTurk and storing them in a product database. Most of the coordination in this case is implicit — through highly structured tasks — and the buyer-supplier relationship is arm’s-length with minimal ongoing interaction. Some Aggregator platforms and third-party companies enable coordination via workflow. Smartling, a New York-based company that manages translation services for websites and mobile apps through its own platform, has built workflow tasks that streamline the translation process and reduce the overall task duration.

The complex interdependencies among tasks and suppliers common in the Governor model require significant coordination, which is the responsibility of the platform, not the buyer. TopCoder and LiveOps deploy a sophisticated proprietary supplier governance layer to enable coordination. More complex jobs may also involve human “platform managers,” who collect project requirements from the buyer at a high level and assume full responsibility for the decisions at lower levels, restricting the buyer’s input to an as-needed basis.

Ensuring Quality Control In all models except for Governor, the buyer is responsible for providing quality control. On a Facilitator platform, the buyer evaluates a single project deliverable submitted by the contracted supplier. To do so, the buyer must have the required expertise in-house. For example, when a supplier hired on Elance for a translation job submits a translated document, the buyer must have the necessary skills to review and assess the quality of the translation.

The Aggregator model poses a different challenge: scale. Here, the buyer must assess the quality of a large number of tasks completed by a pool of suppliers. While the tasks are often trivial, such as product categorization or data entry, checking quality on thousands of them is not. Some platforms offer tools to ease quality control for the buyer. Amazon MTurk, for example, employs a reputation system that evaluates suppliers over time. Others, like microtask crowdsourcing company CrowdFlower, allow buyers to mix “test” tasks into the workload and reject input from suppliers that fail the tests.

Redundant project deliverables submitted by competing suppliers — an approach common in the Arbitrator model — reduces risks and simplifies quality control for the buyer. Choosing from multiple options makes it easier for the buyer to pick the deliverable that fits its requirements best. This may be especially helpful in situations where quality is more subjective. Consider, for example, the common task of developing a logo. Comparing multiple designs submitted by individual designers helps the buyer realize which logo best represents its vision for the venture.

The Governor model assigns responsibility for quality control to the platform using approaches that range from multilevel peer review to supplier testing. Supplier certification is another common approach. When the newspaper USA Today needed to test new mobile apps on many hardware/software permutations, it had software testing marketplace uTest manage the project. uTest certifies its testers by vetting the 1,000 new testers per month against existing testers by having them “play in a sandbox” — that is, perform similar tasks but on a copy of the code being tested.

Managing Risks

For the buyer, the two main risks of a human cloud initiative are project failure (noncompletion) and intellectual property (IP) leakage.

Two models — Arbitrator and Aggregator — have a lower risk of project failure than the others. This is due to the built-in redundancy: multiple redundant suppliers for the job scope means that one failing supplier has little to no impact.

The other models have traditional project failure risks. In the Facilitator model, supplier nonperformance leads directly to delay. While the buyer can respond via financial penalties and negative feedback, these are of little consolation in the case of time-critical projects. A better approach is to rely on thorough due diligence in the Engagement phase of the initiative and close oversight during its Operational phase. Project failure under the Governor model is similar, but the responsible counterparty here is the platform, not the end supplier, thus increasing the leverage of threatened penalties and legal means against an underperforming supplier.

IP risks also vary considerably across the different models. Fundamentally, the buyer is relying on a virtual, distant and often foreign supplier. Of the four platform models, the Aggregator model — with jobs typically comprised of mundane, repetitive microtasks — presents the least risks to IP. In fact, vendors argue that if the tasks are sufficiently atomized, the suppliers cannot even infer what the larger project is about, significantly mitigating IP risk.

In contrast, the Arbitrator model presents the greatest IP challenge. On the one hand, typical Arbitrator jobs, such as industrial design or scientific challenges, require highly skilled suppliers; on the other, the competition model assumes that multiple (often numerous) suppliers have access to all project-related information. The combination of these two factors heightens IP risks for the buyer.

Arbitrators control IP-related risks in a number of ways. By default, all new suppliers joining the platform must sign a legal agreement adhering to IP regulations. The platforms, such as InnoCentive and crowdSPRING, also facilitate IP transfer from the winning supplier to the buyer, often without disclosing the buyer’s identity. On the prevention side, supplier education becomes important. “Our biggest challenge is to educate the community, especially all of the new creatives who join every day,” said one crowdSPRING executive.

Guarding IP under the Facilitator model is also difficult. While it is common to have suppliers sign nondisclosure and noncompete agreements, these are often difficult to enforce, especially with suppliers from developing countries. Under the Governor model, the IP risk is shifted to the platform, which can be held liable if the contract is breached. Many Governor platforms have invested heavily in building safeguards against IP violations. TopCoder, for instance, can make all competitions within the game plan private and conduct background checks on participating coders. This, of course, entails additional cost for the buyer.

In all four models, managing the human cloud will require a deep understanding of best practices for outsourcing and collaborative project management. The person in charge will also need to know how to atomize processes and tasks as well as coordinate and handle input from a number of small, diverse, geographically remote suppliers, often with different cultural backgrounds. He or she will need a sure understanding of nonmonetary incentives, such as reputation building, learning and community engagement.

What’s Next?

Larger buyers like to buy from large suppliers. The two previous sourcing waves, outsourcing and offshoring, really took off only after the supplier marketplace had matured enough to match scale. New human cloud models now offer imaginative solutions to overcome coordination and control barriers involved in dealing with scale — with a large number of microsuppliers. We are already seeing evidence that some large corporations around the globe are beginning to take advantage of these platforms, mainly in the IT arena, but with adoption slowly migrating to other areas as well.

Unlike past sourcing waves, the human cloud will also dramatically benefit small buyers, the largely neglected long tail of global sourcing. They usually do not have the resources and expertise to outsource globally, but human cloud platforms extend these buyers’ reach. A human cloud should prove to be an equalizer for small businesses, allowing firms like Rief Media to compete with large companies that in the past have had the advantage of economies of scale.

The broader sourcing marketplace is also changing. The human cloud will reshape the outsourcing landscape much as cloud computing is reshaping the software industry. We expect traditional outsourcing providers to move into the human cloud domain in the coming years, as some are already using crowdsourcing internally. Moreover, traditional labor-market middlemen are starting to perceive the threat of disintermediation, as human cloud platforms undermine their traditional strengths in providing local short-term labor.

In the coming years, we expect that human cloud platforms will innovate in three directions: task decomposition, real-time work and social governance. Human cloud platforms will develop intuitive visual tools to aid managers in segmenting a project into smaller tasks. Managers will be able to easily create workflows of tasks performed internally with tasks performed externally by a human cloud, leading to the disruption of the business process outsourcing industry. Advances in real-time crowdsourcing, where workers are paid a retainer to remain on call for work requests, will enable new forms of cloud sourcing. Finally, social governance techniques, which allow the best workers to manage, train and approve the work of others, will continue to evolve. Together, we expect all three directions to lead to a migration of many tasks from the Governor model to the Aggregator model.

Today, the human cloud is a small part of the global sourcing landscape. But it is growing rapidly as it continues to evolve. Major outsourcing and offshoring vendors are already experimenting with human clouds and likely will embed them in the services they provide. The pure-play human cloud platforms have already aggregated a global labor supply of millions of professionals. Now they need to find more customers who can use their services. We believe it is just a matter of time before they succeed in making the match.

References

1. massolution, “Crowdsourcing Industry Report: Enterprise Crowdsourcing — Market, Provider and Worker Trends” (Los Angeles: massolution, February 2012).

2. Two other related phenomena are human computation and collective intelligence. Human computation takes advantage of human participation directed by a computational process in order to solve problems that computers alone cannot yet solve. For example, Google-owned reCAPTCHA leverages human computation to transcribe books and newspapers for which optical character recognition is not yet effective. Collective intelligence is more of an umbrella term that covers phenomena in which, as Malone, Laubacher and Dellarocas write, “large, loosely organized groups of people work together electronically in surprisingly effective (and seemingly intelligent) ways.” Examples of collective intelligence range from Linux, the first major open-source software development community, to Threadless, an online community where members submit and vote on T-shirt designs that the company then manufactures.

While human-cloud initiatives can include elements of both human computation and collective intelligence, the concept of the human cloud is narrower in scope and focuses only on paid outsourcing arrangements that involve a buyer, an intermediary platform and a pool of virtual suppliers. See A.J. Quinn and B.B. Bederson, “Human Computation: A Survey and Taxonomy of a Growing Field,” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York: CHI, 2011), 1403-1412; and T.W. Malone, R. Laubacher and C. Dellarocas, “The Collective Intelligence Genome,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51, no. 3 (spring 2010): 21-31.

3. J. Howe, “Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd Is Driving the Future of Business” (New York: Crown Business, 2008).

4. massolution, “Crowdsourcing Industry Report.”

5. Our framework extends the arguments put forth by Malone, Laubacher and Johns in their recent article “The Age of Hyperspecialization.” While their primary focus is on microtasks (covered by the Aggregator model in our typology), our discussion spans the entire human cloud landscape. See S. Cullen, P. Seddon and L. Willcocks, “Managing Outsourcing: The Life Cycle Imperative,” MIS Quarterly Executive 4, no. 1 (March 2005): 229-246; and T.W. Malone, R.J. Laubacher and T. Johns, “The Age of Hyperspecialization,” Harvard Business Review 89 (July-August 2011): 56-65.

i. massolution, “Crowdsourcing Industry Report.”

Comment (1)

Forget the cloud, use humans instead | The New Economy