The Case for Contingent Governance

To cure weak corporate governance, new regulations and codes of best practices might be necessary, but they won’t be sufficient. What is also required is the acknowledgment that governance has to continually adapt to changing conditions because a company, its management and business environment are forever evolving. As a result, corporate boards must adopt the right roles to reflect and shape those governance conditions.

In an ideal world comprising competitive markets and transparent information, the legal system and market processes would, by themselves, provide perfectly adequate corporate governance. Specifically, the markets would weed out and penalize — through declining share prices and takeovers — executives who tried to manipulate their companies in any way that was adverse to long-term value creation. Everything affecting value creation (including environmental costs such as pollution) would be priced by the markets and rewarded or punished in line with the contribution to or subtraction from value creation that those factors engendered.

Indeed, if the market could capture everything and no one could manipulate decision making with monopoly power, companies that maximized their economic value (the difference between projected revenues and the market cost of all the resources used) would also maximize the public good.1 The real world, however, is far from ideal. Thus, governance is necessary to deal with the things that fall outside markets as well as the people who would manipulate decisions in their own interests.

Two broad streams of commentary and research deal with these issues and the need for different governance roles. Sociologists have explored the role and impact of companies on society, especially the relationships between organizations and other stakeholder groups.2 Markets alone do not capture the full impact of companies; in particular, they do not price certain inputs and outputs of the business, so-called externalities, such as the effect of an organization’s activities on society at large. Thus, regulations and governance are needed to deal with the consequences of those externalities, especially those promoted by stakeholder groups. But the right role of the board depends on the importance of the externalities, which can vary from country to country and from market to market over the life of the company.

Economists have explored how shareholders can get managers to run a company as agents acting in the owners’ interests, given the appropriate regulations and incentives.3 But the recent slew of corporate scandals has revealed a widespread managerial abuse of power, despite regulations and the best incentive systems. The reason is that regulation is rarely optimal, markets are not efficient, and information can never be fully transparent. Inside an organization, top managers pursue power and wealth; outside the company, directors, shareholders, regulators, unions, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and governments want influence. Each side inevitably tries to distort the governance system to its advantage, but managers have the advantage of their monopoly on power and access to inside information. Thus the right role of the board depends on the importance of the agency problems, the difficulty of getting managers to act in the owner’s interests, which can vary over the life of the company, and the tenure of each CEO.

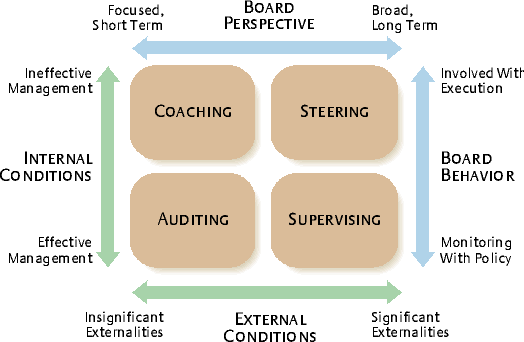

To deal with externalities and agency problems, boards have an ongoing portfolio of activities, including auditing, oversight mechanisms, company policies, compensation incentives, succession planning and so on. But boards are influenced by economic, sociocultural, psychological and political forces, which each have their own separate, independent dynamics. At any period in time, to avoid confusion and to pursue a direction in dealing with the current conditions facing the organization, boards must emphasize a particular subset of activities in decision making and resource allocation. The dominant subset of those activities is called the driving governance role.

The driving governance role must change with shifts in the importance and nature of the externalities that shape the agendas of shareholders and stakeholders, as well as with shifts in the agency problems created by dysfunctional managerial power. A change in the driving governance role does not mean that one set of activities is abandoned for another. Instead, a different subset of those activities becomes dominant in decision making and resource allocation. See Sidebar

Focused Versus Broad Governance

Because information can never be fully transparent, boards always have the fundamental fiduciary responsibility of auditing the financial performance of companies to ensure that they are being run in the interests of their owners. A focused view of governance restricted to the auditing role is appropriate in markets with insignificant externalities.

However, when markets are not efficient and well regulated, boards have to deal with the factors that fall outside the markets and regulations. If the externalities are excluded and ignored, they may come back to undermine the long-run economic performance of the company. But taking externalities into account can be expensive and is often not in the short-term interests of the key players. Moreover, it is frequently unclear which unpriced factors are important for long-term success. Nevertheless, there are a number of contexts with externalities that the boards of successful companies are addressing of their own accord by broadening the scope of their oversight and policies. These include emerging economies, markets in transition and markets with influential NGOs.

The boards of companies active in emerging economies have to take an even broader view of their oversight and policy responsibility because value creation in emerging markets requires a wider range of company activities than in the developed world. Many essential inputs might be missing or of substandard quality. For instance, the legal system might be inadequate; government services could be unreliable; bribery and corruption might be commonplace; infrastructure such as roads could be inadequate; and suppliers might not have the finances and equipment necessary to manufacture goods to the desired specifications.

The board has to develop oversight and policy standards to ensure that management puts in place local rules of corporate governance both to address the inadequacies in the external environment and to avoid compromising the long-term future of the company. Oversight of societal impact and ethical standards are essential, for example, to prevent the type of externalities that have confronted Nike Inc.’s board (with respect to charges of using child labor) or Wal-Mart Stores Inc.’s board (with respect to allegations of employing illegal immigrants). Companies that are successful in emerging economies typically invest in the local communities where their plants are located, providing education and social services. They prohibit bribery, and they have financial standards that include longer payback periods, thus providing the time needed to deal with such externalities.

Markets in transition, such as recently deregulated markets or those created by new technology, also require a broader governance perspective than that dictated by short-term market forces. In certain respects, Enron Corp.’s collapse was due to woefully inadequate governance oversight and policies for dealing with the long-term risk in the new derivative markets that the company created. While Enron was inappropriately pricing the long-term risks it was taking on, some of its customers in the deregulated electricity market in the United States skimped on investing in new capacity and faced an embarrassing series of power outages. Similarly, the private railway companies that emerged after deregulation in the United Kingdom skimped on investing in safety and paid the price with a series of fatal accidents. In these cases, governance oversight and policies were too narrowly focused on short-term financial auditing and ignored the longer-term impact of inadequate risk management and investment.

Influential NGOs often emerge in response to externalities with negative societal impacts that are either unpriced by the market or are perceived to be inadequately regulated. One such example is the campaign led by Ralph Nader to highlight safety problems with General Motors Corp. vehicles, an effort that developed into an automobile-safety lobby. The activism of NGOs signals that companies need to broaden their governance perspective and develop policies for engaging with the NGOs.4 For example, it took many years for Nestlé S.A. to adopt such measures in dealing with NGOs on the issue of infant formula and breastfeeding. And Shell completely discounted the impact of the NGOs that protested the proposed disposal of the Brent Spar oil rig in the North Sea. Even when the NGOs may be technically wrong about the issues they are espousing, they represent nonmarket forces that need to be incorporated into governance oversight and policy.

Monitoring Versus Involved Governance

When managerial power is effective, in the sense that it promotes the creation of long-term economic value and does not manipulate the way that value gets shared, the board can restrict its activity to monitoring the value-creating performance of the company and developing policy to govern the distribution of value to shareholders and other stakeholders.

However, when managerial power is dysfunctional, in the sense that it either does not promote value creation or it manipulates the distribution of value to its advantage, the board has to become more involved. This means changing its activities from oversight and policy setting to taking a more active part in the conduct of the firm at the top. The most common examples include contexts in which performance is poor, either financially or in dealing with externalities; the CEO makes major strategic moves unilaterally (that is, without consulting the board); ethical or transparency standards are breached; or the CEO asks for excessive compensation that is not linked to performance.

The need to get involved and stand up to CEOs calls into question the power balance between the CEO and the board. This balance varies with length of service of the CEO; the personalities of the people involved; their background, experience, relationships and network; their involvement in the hiring and evaluation of the CEO; and the recruitment of nonexecutive board members.5 Changing this balance of psychological, cultural and political forces and moving from a monitoring role to a more involved role is one of the board’s biggest challenges.

Dealing with poor performance or major unilateral moves is a special challenge when it involves long-serving CEOs whose early performance had been good. Blowing the whistle is especially difficult when the CEO has built up credibility and power relative to the board and when the board is in a comfortable monitoring role. The passive role of GM’s board during the decades after World War II is a classic example of the difficulty of reversing course, even when major externalities and poor performance become evident.

As GM increased its revenues and financial market value through World War II and beyond, top management became so powerful that the only real role left for the board was one of auditing. It took 10 years, until a board meeting in 1970, before GM responded to safety and pollution externalities with two new committees. Then, when the Japanese began making serious inroads into the U.S. market after the oil crisis of the early 1970s, GM failed to respond again, apart from seeking import protection together with the other U.S. carmakers.

When GM finally woke up to the challenge of new competition in the 1980s, the board did nothing to prevent management’s drive to spend $90 billion on new high technology and acquisitions that could not be digested organizationally. During this period, the board was no more than a rubber stamp for the ideas and plans of then CEO Roger Smith. According to a Fortune article published in 1992, “Roger Smith kept the board on a very short leash. He withheld key financial data and budget allocation proposals until the day before the meetings and sometimes distributed them minutes before the participants convened.”6

Also, when the board is relatively weak, CEOs are tempted to take personal advantage of their monopoly on certain kinds of information, contacts and resources — both financial and human — in particular, the information needed to shape the direction of the firm and assess its long-term value. Past research has found that CEOs with weak boards of directors tend to receive greater compensation than CEOs with powerful boards.7 Two well-known extreme examples: between 1999 and 2001, Kenneth Lay took home $247 million, while Enron was misleading investors and employees; Gary Winnick pocketed $512 million over the same period, while Global Crossing was collapsing. The increasing concern among shareholders over the distribution of value is putting pressure on boards to get involved sooner to constrain the violation of ethical standards and the manipulation of value distribution.

Four Main Roles

Although each set of conditions requires an emphasis on a particular subset of board activities, it is useful to distinguish between four basic types of governance roles: auditing, supervising, coaching and steering. (See “Dominant Board Perspectives, Behaviors and Roles.”) The roles reflect two main differences in board culture. First, boards can be concerned mainly with shareholder interests, or they can also take into account the interests of other stakeholders to deal with important externalities. Second, boards can restrict their activities to monitoring, or they can be involved in the conduct of the organization at the top to deal with ineffective management. These basic role types are not mutually exclusive in terms of board activities; instead they reflect different board cultures that result from different emphases on decision making and resource allocation. During any time period, a board must determine what its dominant role should be, given the current conditions.

Auditing Role

When management is effective and externalities are insignificant, boards should assume an auditing role. The dominant activity here is the fundamental fiduciary responsibility of monitoring company performance in the interests of the shareholders. Competitive markets and efficient regulations are sufficient to handle all significant externalities, and top management is effective in creating and distributing value. As a result, the financial audit committee dominates the board, and the primary behavior is monitoring for alignment with policies. Also, the perspective is focused and short term.

An auditing role is appropriate in stable business environments that do not require large investments or big moves with high external impact. Such conditions are common, for example, when small and midsize businesses have effective CEOs, are not growing rapidly and are not big enough to generate nonmarket effects that may eventually undermine long-run economic performance.

Supervising Role

When externalities are important, the board can still limit itself to a monitoring role if management is effective. But the perspective of the board has to go well beyond its fiduciary responsibility to incorporate oversight and policy for the strategic, societal and risk effects of those externalities. This means incorporating the interests of other stakeholders. Although the financial audit committee still must play an important role, other board committees have to take the lead in supervising management’s response to issues of social responsibility, long-term strategy and risk management. Thus, the mix of board members has to shift to include experts who can deal with such concerns. And most importantly, the decision-making criteria have to include multiple objectives, especially the ability to make trade-offs between short-term financial performance and longer-term value creation, and those trade-offs should continually incorporate feedback from the externalities. All of this amounts to a basic shift in the culture of the board to what can be called a supervising role.

A supervising role is appropriate when a large, powerful company with effective management makes strategic moves that create value over the long run but have significant risks or have an impact on society outside the company’s markets. The supervising role is especially important when a company is considering big moves; it is essential for high-risk businesses with strong, effective CEOs who are involved in deal making and large investments.

Coaching Role

When the CEO and other top executives are ineffective in creating value or when they manipulate value distribution to their advantage, the board has to move from a monitoring role to more active involvement. When the externalities are insignificant, the board can restrict its perspective to a focused short-term view, dealing with the CEO and the top team. However, this requires the board members to go beyond oversight and policy and move into active coaching (and perhaps even reprimanding) of the executives involved.

To do so, the board has to change the power balance and establish its independence from the CEO with the independent leadership of outside directors or by splitting the roles of CEO and chairman of the board. In some instances, the board has to have the wherewithal to remove weak CEOs. In other cases, it has to coach and counsel CEOs who are working their way into their roles. In fact, coaching is often the primary function of boards that appoint a new CEO from outside the company. Venture capitalists also play a coaching role in startups because the founders are often inexperienced in management.

Steering Role

When management is ineffective and the business is affected by a number of nonmarket factors, the board has to go beyond either coaching or supervising and become actively involved in execution with a broad, long-term perspective. This steering role typically incorporates dealing with significant externalities when top management doesn’t have the requisite expertise. Alternatively, when an incompetent CEO has to be replaced, the board might have to temporarily delegate and support one of its members as interim CEO during the transition.

In a steering role, the board takes the reins in dealing with externalities, such as problems with government authorities or NGOs. This requires more than a committee that investigates the issues. It calls for the ability to interact, negotiate and possibly lead combined working groups with outside stakeholders. Ultimately, the board might also have to ensure the implementation of the company’s agreements with those stakeholders. The task requires deft people skills and a keen sense of the politics of public groups and coalitions.

Recognizing Shifts in Governance Conditions

The right driving role does not remain static but evolves with changes in the externalities in the market and the agency problems created by ineffective management. The first step is to recognize — or, even better, anticipate — when a change in conditions calls for a shift in the dominant governance role. That requires an awareness of certain basic patterns.

Patterns in the Development of Externalities

Three types of patterns are commonly associated with the emergence of new externalities: economic and political cycles, industry and business-model shifts and organizational crises. For a good example of those factors at play, consider the story of the collapse of Swissair.

For years, Swissair was associated with reliability, punctuality and first-class service. The Swissair board included many of the most respected CEOs of large Swiss multinationals, as well as personalities from the public sector. Being a Swissair board member was a “certification that one had arrived in the corridors of power. … It was a monument that you were asked to join as a kind of honor.”8 In the late 1980s and 1990s, none of the board members had a background in the airline industry. As one who later became chairman put it, “I am not a friend of the notion that at the board level one should in a way duplicate the management requirements. Management has the know-how to lead the airline. The board has other tasks; it must especially carry out the monitoring function.”9

In 1987, the European Commission introduced a three-phase deregulation of the airline industry in Europe, which led to the emergence of low-cost competitors like Ryanair, easyJet Airline and Virgin Express. Not surprisingly, given its history and composition, the Swissair board made no move away from its dominant monitoring role toward more of a supervisory one, and instead of responding directly to the shift in industry conditions, it pursued its global ambitions by joining Delta Air Lines and Singapore Airlines Ltd. in the Global Excellence Network.

In December 1992, the Swiss population voted against joining the European Common Market, and Swissair feared being locked out of that market. Within a few months, the company announced plans to set up a jointly owned entity, to be known as Alcazar, with Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), KLM Royal Dutch Airlines and Austrian Airlines. But the agreement failed at the end of 1993, with concerns among the Swiss public and parliament about massive layoffs and the loss of Swissair’s identity. Rather than play an active steering role in dealing with those stakeholder concerns, though, the Swissair board was still trapped in its traditional monitoring role.

In 1994, on the advice of the consulting firm McKinsey & Co., Swissair’s management proposed a radical shift in business model toward becoming a “network manager.” In that capacity, the airline would perform the brain function of an alliance, “integrating network and product design, scheduling, yield, pricing, brand management and sales, while purchasing both ‘flying and nonflying’ services from other providers.”10 This strategy involved taking equity stakes in national or regional carriers, so Swissair borrowed to take a 49.5% stake in Sabena, the ailing Belgian national airline. The Swissair board, which was still in a monitoring (and not supervising) role, approved the move.

Patterns in the Development of Agency Problems

During the tenure of a CEO or other top executive, the board’s role might shift from coaching (when that person first takes over) to steering (if the individual runs into externalities that he or she can’t handle or becomes dysfunctional in terms of either creating value or distributing it). The continuation of the Swissair story illustrates these patterns.

In 1996, on the retirement of then CEO Otto Loepfe, the board appointed the chief operating officer, Philippe Bruggisser, to replace him. In the absence of coaching from the board but working with McKinsey, Bruggisser proceeded with the network-manager strategy, reorganizing the company into a holding structure, called the SAir Group, with four divisions: SAirLines, SAirLogistics, SAirServices and SAirRelations. Those entities had operations around the world in the air-travel and hotel industries.

Bruggisser scored some early successes. He produced a good profit performance in 1997, which the media touted, and he deftly managed the company throughout the tragic Swissair crash off the coast of Halifax in 1998. To accelerate implementation of the network-manager objective, Bruggisser carried out McKinsey’s recommendation of a “hunter strategy,” taking minority investments of up to 30% in a German tour operator, LTU; three small French airlines, AOM, Air Liberté and Air Littoral; LOT Polish Airlines; and the South African national airline, SAA.11 Except for LOT, the airlines involved were in poor financial shape. On the advice of management, the board approved these investments for a total of 4.1 billion Swiss francs.

But differences at the top between Bruggisser, who was CEO of SAir Group (the holding company), and Jeffrey Katz, then CEO of Swissair, over the personal ambitions of Katz, who had come from American Airlines, led to the collapse of a potential partnership with American. With the board far from playing the necessary coaching role, Bruggisser then proceeded on his own to explore a full merger with Alitalia Airlines, which required additional investment. Later, Bruggisser would claim that the board showed little detailed interest in what he was doing, approving all his proposals and budgets.

However, when McKinsey produced a report in August 2000 showing that an additional 3.25 billion to 4.45 billion francs would be needed, a new member of the board, Mario Corti, the CFO of Nestlé, started asking detailed questions that exposed the fragility of the company’s financial position. Finally on Jan. 23, 2001, the board took action, switching into a steering role. The hunter strategy was scuttled; Bruggisser’s 22-year career came to an end; and the chairman of the board, Eric Honegger, became the interim CEO.

But the story doesn’t end there. Later, when the true financial position emerged as worse than advertised, nine of the 10 board directors resigned, and Mario Corti took over as the new chairman and CEO. He replaced auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers with KPMG, and in April 2001 he announced a loss for the previous year of 2.9 billion francs (due to a write-off of investments in other airlines and provisions for financial obligations assumed with those deals) as well as an increase in debt from 13 billion to 19 billion francs (due to the recognition of previously off-balance-sheet financing).

The working style of the new board was different. The directors received the financial figures every month and met every other month to evaluate the performance of the SAir Group. Working closely with management, the board introduced initiatives to sell noncore businesses, such as the hotels and stakes in the other airlines. At that point, the board was very much in a steering role.

But it was too late. The deepening recession after the collapse of the dot-coms and the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 aggravated Swissair’s worsening liquidity position. On Sept. 21, 2001, Moody’s downgraded the company’s debt to junk status. A little more than a week later, all its aircraft were grounded, leaving 20,000 passengers stranded. When suppliers demanded immediate reimbursements, the company couldn’t pay for jet fuel. Shortly thereafter, the SAir Group went into receivership.

A striking thing about the Swissair story is the way in which the board never came close to a supervisory role despite the increasing risk of the hunter strategy. The board remained passive even when problems became manifest on the front pages of the press, as the partner airline unions balked at the network strategy. As for any coaching role, over the years the board had outsourced that function to McKinsey. In the absence of board supervision, though, consultants cannot play that kind of role properly because of conflicts of interest. McKinsey had much to lose in client fees if it were to recommend that Swissair’s management drop the increasingly risky network-manager and hunter strategies.

Preempting Governance Problems

Swissair’s story might provide a stunning example of a board’s failure, but the governance issues the airline faced are hardly unique. Several measures can help boards to preempt similar kinds of problems.

Anticipatory Mechanisms

The board needs early-warning mechanisms to detect situations that call for a shift in the driving governance role. To pick up changes in externalities, it has to delegate that responsibility to individual members or subcommittees, as the need requires, so that they can monitor the societal impact of the company’s activities as well as determine the longer-term strategic and risk effects. The board also has to set aside some time on its agenda to discuss those topics, and it should request periodic reports both from the designated members (to determine how political, economic and industry events are affecting externalities) as well as from management (to assess the impact of industry, business-model and organizational changes).

To anticipate any agency problems associated with the CEO, the external directors have to distance themselves from that person. They can do so only by meeting periodically without the CEO and those directors who have ties to the company. Their report back to the full board should include an evaluation of the performance of the CEO and the top-management team in terms of value creation, ethics and transparency, as well as an assessment of how the board’s policies are affecting the long-term health of the company.

Periodic Audits of Board Processes

The board must periodically perform a self-evaluation, based on ongoing dialogue and confrontation of the issues. The purpose is to determine the appropriate balance in the distribution of power between top management and the independent external directors and to ascertain that the right governance roles are driving board deliberations and supporting the value-creating model of the company in sync with the business environment. Corporations that have introduced formal evaluations of their boards include Motorola Inc., Computer Associates International Inc., the Walt Disney Co. and Charles Schwab & Co.

The most difficult task — and therefore the one most likely to benefit from the help of outsiders — is the assessment of the dominant governance role, in terms of the culture of decision making, resource allocation and board action. Is that culture one of financial monitoring (auditing role), or multiple objectives and policy trade-offs between the short and long run (supervising role), or involvement with the CEO’s development (coaching role), or active board initiatives to offset weaknesses in the top-management team, especially in managing externalities (steering role)?

Shifts in the Driving Governance Role

The key to preempting governance problems is the ability of the board to shift its dominant role early enough to deal with emerging issues. In addition to anticipation, this calls for role flexibility, which can be enhanced in several ways.

First, the board must pay sufficient attention to the range of competences needed to deal with emerging externalities. The task is difficult because of the countervailing need for board members to work together. Over time, the composition of the board has to change and new board members have to be appointed to provide newly required expertise. This has been especially true since the recent corporate scandals increased the demand for ethical behavior and transparency. Furthermore, the approach of the nominating committee in anticipating future requirements and reconciling them has to be reviewed carefully. To obtain a broad view, companies such as Sun Microsystems Inc. have recently moved toward having a majority of outsiders with diverse backgrounds on their boards. Others, such as AT&T and Kimberly-Clark Corp., have ensured that financial experts sit on their boards’ audit committees.

Second, separation of the external directors from the CEO is essential to counterbalance the power of the latter. At a minimum, periodic separate meetings of the external directors are necessary to perform the anticipatory and assessment tasks discussed earlier. A greater number of companies, notably Disney and General Electric Co., have organized for independent leadership of their outside directors. Additional mechanisms include movement toward separating the positions of CEO and chairman of the board (in countries where that practice isn’t yet common) and reinforcing the position of chairman (in countries where it is).

Third, boards that have the resources should develop a range of activities tied to different board members or subcommittees: oversight of strategic, societal and risk effects; policies for ethics, transparency and compensation; processes for succession planning; coaching and so on. Then, when a shift in the dominant subset of activities and related board role is required, the new driving role doesn’t have to be acquired from scratch. Instead, it can be installed quickly by shifting the composition and locus of power in the executive committee.

Fourth, the composition of the executive committee should be reviewed annually with respect to the dominant role type represented and its fit with the environment. When there’s a warning signal of an important shift in governance conditions, the composition of the executive committee should be altered by drawing on the relevant subcommittee and making a corresponding change in the board’s approach to decision making.

Finally, because human beings are generally not adept at self-evaluation and monitoring, a recommended practice is for boards to file an annual report to describe how they are dealing with externalities and agency problems. This document might be submitted to the annual general meeting of shareholders as well as to a public agency, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission. At the very least, this practice will encourage boards to take a more active role in monitoring and governing themselves as well as the organizations they oversee.

References

1. M. Jensen, “Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory and the Corporate Objective Function,” in M. Beer and N. Nohria, eds., “Breaking the Code of Change” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

2. For an integrated perspective that puts social responsibility in the foreground, see R. Monks and N. Minow, “Corporate Governance,” 2nd edition (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 1995).

3. A key article is that by M. Jensen and W. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3 (October 1976): 305–360.

4. U. Steger, N. Kong, A. Ionescu-Somers and O. Salzmann, “Moving Business/Industry Towards Sustainable Consumption: The Role of NGOs,” European Management Journal 20 (April 2002): 109–127.

5. A. Lank and F.-F. Neubauer, “The Power Balance Between Board and Management in the Family Business: Its Governance for Sustainability,” chap. 3 (Hampshire, U.K.: McMillan Press, 1998).

6. A. Taylor, “What’s Ahead for GM’s New Team,” Fortune, Nov. 30, 1992, p. 59.

7. F. Elloumi and J.-P. Gueyie, “CEO Compensation, IOS and the Role of Corporate Governance,” Corporate Governance 1, no. 2 (2001): 23–33.

8.“Who Lost Swissair?” Institutional Investor 36, no. 2 (2002): 42–50.

9. H. Krapf and U. Steger, “The Grounding: Did Corporate Governance Fail at Swissair?” IMD case no. IMD-3-1057 (Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD, 2002).

10. C. Barton, L. Bradshaw, R. Brunschwiler and T. Bull-Larsen, “Industry Focus: Is There a Future for Europe’s Airlines?” McKinsey Quarterly, no. 4 (1994): 29.

11. S. Hamilton and I. Francis, “The Collapse of Swissair,” IMD case no. IMD-1-0198 (Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD, 2003).