When Marketing Practices Raise Antitrust Concerns

Many common marketing activities are coming under greater scrutiny from regulators, lawyers and scholars. Companies are scrambling to figure out how that will affect competition.

Antitrust laws can give managers a sobering dose of reality — even managers who believe they are obeying the laws. These days, most business-people know better than to sit down with competitors to fix prices or divide markets, and most are alert to the perils of pricing below cost until competitors fail. However, when considering core marketing issues such as distribution policy, line extensions or joint marketing agreements, or even when trying to enhance the company’s “good citizen” image, they may not realize the growing likelihood of violating antitrust laws. They are especially likely to do so when their brands hold dominant market shares.

The issue is particularly sensitive in the United States, where longtime federal statutes such as the Sherman Antitrust Act are being interpreted with economic rigor. But it applies outside the United States as well; for instance, the European Union’s directives are taking a harder line with antitrust interpretations. For the purposes of this article, we will refer only to U.S. situations.

While marketing practices received increased antitrust scrutiny beginning in the late 1990s,1 a series of events in the early 2000s has reinvigorated the legal thinking regarding marketing concerns and antitrust. There is little debate that the new emphasis is due to significant changes in business practices concerning promotion, sales and distribution. The retail sector’s category management is one example: There has been a shift from each supplier having its own retailer relationship for management and stocking of its products to a practice in which the retailer may entrust one supplier with operation of an entire category of merchandise. What has spurred business interest is a series of challenges to the changed practices leading to verdicts with substantial damages awarded, most notably theConwood case (discussed below) and its billion-dollar verdict.2 Federal antitrust enforcement officials, in particular the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, have begun to scrutinize retail practices such as category management and slotting allowances.3 Academics have also renewed their interest in the topic, in large part spurred by the cases mentioned above.4 In sum, as the marketing world has changed, antitrust lawyers, scholars, enforcement officials and especially competitors affected by these changes have scrambled to understand how the new practices affect competition.

The lesson here is that the degree to which a company dominates a market may dictate the degree to which the practices in which it engages are illegal. We have chosen to underscore that principle by offering five concrete examples of marketing practices that have given rise to antitrust liability, the threat of liability or litigation resulting in settlement. The examples we have selected are usually the pivotal cases in their fields. Our goal is to bring the risks to life and suggest implications for managers’ decisions. As a crucial first step, it is helpful to understand how antitrust enforcement agencies and the courts undertake analysis to decide whether particular conduct violates antitrust laws.

The Role of Dominance in Antitrust Analysis

The actions of dominant companies may spur antitrust concern based on their intent or on the effects of those actions in eliminating competitors, expanding the companies’ dominance in particular markets or expanding their dominance to other markets. They may also spur such concern if they injure the interests of consumers by raising prices, limiting choices or reducing innovation. It is reasonable to ask whether such actions would be illegal regardless of company dominance (certainly, they might be), but antitrust enforcement agencies will employ a specific two-step analytical process to examine the conduct of dominant companies. First, the concentration of the relevant market will be considered. If the market is determined to be unconcentrated, then, with a few obvious exceptions,5 the analysis will stop.

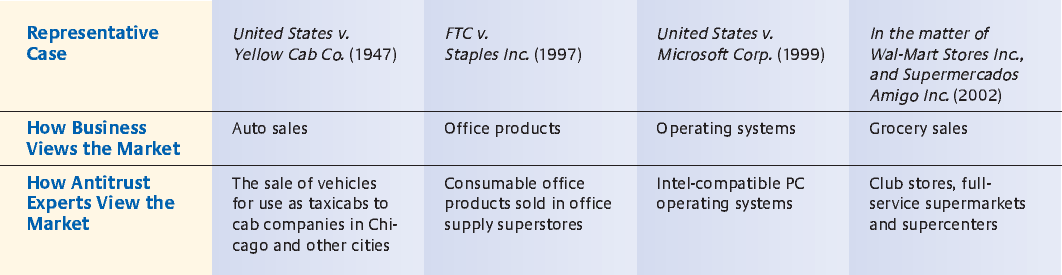

Obviously, a crucial step in the analysis is the determination of the relevant market in terms of both its geographic and product boundaries. Herein lies a danger for managers. They may believe they need not worry because they can point to a wide range of competitors, but antitrust analysis may define the market more narrowly. (See “Differing Perspectives of ‘Relevant Markets’.”) From an antitrust analyst’s viewpoint, the primary purpose of defining markets is to determine whether the conduct in question harms or will harm competition. The lesser the degree of market concentration,6 the greater the effect the conduct must have in order to injure markets.7 The more concentrated the market, the more likely the injury to competition — even when the acts seem innocuous to managers.

When an antitrust enforcement agency decides that a market is concentrated, it will continue its analysis to determine the extent to which the concentration is a problem. First, its method of calculating market shares8 recognizes the importance of differences in the relative size of the market’s participants — if a market has one dominant leader, for example, smaller competitors may merely follow the behavior of that leader.9 The crucial point is that market shares are thebeginning of most antitrust analyses, and while dominance need not indicate an antitrust problem, lack of dominance in many instances is likely to preclude it.

Once dominance has been determined, antitrust analysis focuses on how a company mightexercise market power. A current example is the Procter & Gamble Co.’s proposed acquisition of the Gillette Co.10 (At press time, the acquisition was partway through the Federal Trade Commission’s review process.) P&G’s stated rationale for the acquisition is to increase its bargaining power with giant retailers such as Wal-Mart Stores Inc. — to become as essential to the retailers as the retailers now are to them. However, it may be determined that the combined corporation has dominance in some health and beauty aids categories and that such dominance might be enhanced by the combined companies’ role as category captain, among other things. P&G’s situation is by no means unique. As a vendor gains power, it may use its leverage not only against retailers but also against its smaller competitors, for example, by elevating the costs to retailers of doing business with the smaller vendors. The effects of such exclusionary conduct might include increased prices to consumers, fewer choices and reduced innovation. The purpose of the antitrust laws, and the role of the enforcement agencies, is to prevent and restrain practices that, in some cases, may lead to such consequences.

In general, the responses of federal and state antitrust agencies and private plaintiffs have lagged the marketing initiatives of the business world. But the message of the discussion presented here is that they are rapidly closing the gap, and activities that have become part of the repertoire of marketing managers are coming under far more scrutiny from antitrust regulators. Clearly, a tension exists between the need to compete effectively — aggressively, even — and the need for caution concerning antitrust, and excellent marketers learn to keep both perspectives in mind simultaneously. Such a dual perspective is gained most easily by examining antitrust decisions and by subsequent discussion of approaches to anticipating and preventing antitrust problems. Following are examples of five different danger spots.

Category Management as an Exclusionary Device

Category management is a well-known method employed by retailers to maximize profits by managing categories of competing product brands as strategic business units, allocating shelf space to various sizes and types of each brand.11 Category captains decide shelf arrangements and allocate shelf facings. Sometimes an employee of the retailer assumes this role and will consult with suppliers, whose data concerning consumer preferences and past buying patterns will suggest priorities for prime shelf space. More often, though, the category-captain role will be delegated to such a supplier, and this is where antitrust issues are surfacing.

The supplier that typically assumes the category-captain role is the dominant supplier. If the supplier then abuses its position, the outcome can be very serious, as managers at one moist tobacco supplier found out. The moist tobacco (snuff) category, at issue in the recent case ofConwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co.,12 is one in which point-of-sale promotion is particularly important, given the laws regulating use of tobacco and its advertising. United States Tobacco Co. of Greenwich, Connecticut, maker of the well-known Copenhagen and Skoal brands, enjoyed 100% of the snuff market until the 1970s, when competitors, including Conwood Co. LP, of Memphis, Tennessee, entered the market with lower-priced brands, driving United States Tobacco’s market share down to 77% by 2000.13 Conwood makes brands such as Levi Garrett and Kodiak.

United States Tobacco played the role of category manager in many stores, including Wal-Mart, and that role formed the basis for legal action alleging that the company misused its position. First, Conwood alleged, United States Tobacco provided misleading information to retailers about how competitive brands were selling. Second, United States Tobacco initiated a Consumer Alliance Program (CAP), offering retailers a 0.3% discount for providing United States Tobacco with sales data, participating in its national sales programs and giving the best placement to United States Tobacco racks where competitive racks were present. Third, Conwood alleged that United States Tobacco entered into exclusivity agreements with some stores so that its racks were the only ones displayed. Conwood also charged that United States Tobacco sales personnel removed Conwood’s point-of-sale displays, in some cases literally breaking them up, and that the tobacco leader paid bonuses to its employees based on the number of Conwood racks they removed.14

Testimony showed severe anticompetitive effects on Conwood and on consumers — and revealed some very colorful statements by United States Tobacco staff. (See “Damning Verbatims From the Conwood Case.”) From 1997 to 2000, Conwood’s Wal-Mart market share declined from 12% to 6.5%, and for every 10% increase in United States Tobacco shelf facings, snuff prices increased by 7 cents. Over 37,000 retailers signed up for United States Tobacco’s CAP program, accounting for 80% of all the firm’s snuff sales nationwide. As Conwood lost shelf facings, consumers were left with fewer snuff options, particularly for lower-priced brands.15

At trial, the jury awarded damages to Conwood. On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit concluded in part that misuse of the category manager position, exclusive rack agreements and United States Tobacco’s other conduct were part of predatory conduct and not merely “isolated tortious activity.” United States Tobacco had market power in the snuff market and used that power to entrench its position. While some of the tobacco corporation’s conduct could be challenged under tort law, the effect of anantitrust challenge against United States Tobacco was to award Conwoodtreble damages.16 The U.S. Supreme Court declined review, leaving United States Tobacco with a $350 million jury verdict that was trebled because of the antitrust violation to $1.05 billion17 —almost twice the net earnings of the company today.

Nobody is contending that snuff is a typical category in terms of the importance of in-store displays; legal restrictions on advertising and sales promotion for tobacco products make such displays particularly critical. But there is no reason to assume that category leaders in other product areas cannot face successful lawsuits for behavior that could be viewed as anticompetitive.

Discounts and Incentive Programs as Exclusionary Devices

Discounts to retailers clearly were part of the problem inConwood. However, even where discounts are not tied to the exclusive distribution of the brand offering them, they can lead to antitrust problems if they provide incentives for retailers to favor the dominant company’s products over those of its competitors. One recent example comes from the transparent tape market. 3M Co.’s Scotch brand held 90% of the market in the early 1990s, but buyers were increasingly purchasing private-label or “second brand” transparent tape supplied by LePage’s Inc.18

To counter LePage’s, 3M offered bundled rebates to retailers while simultaneously entering the private-label tape market. Through its Executive Growth Fund and Partnership Growth Fund, 3M offered rebates to induce retailers to eliminate or reduce purchases from LePage’s. These were not volume discounts. Rather, the discounts were dependent on purchases of other 3M product lines (health care, home care, home improvement, home office supplies and retail automotive, for example). The size of the rebate 3M offered was a function of the number of product lines in which retailers met customer purchase targets. Moreover, if a retailer failed to meet the target in any one line, including transparent tape, it would lose the rebate inall categories. Wal-Mart, for example, stood to gain $1.5 million by meeting 3M’s targets in all of the company’s product lines that it sold.19 LePage’s claimed that 3M’s payments to some large retail customers were high enough to effectively endow 3M with “exclusive supplier” status.

The evidence suggested that 3M only entered the private-label tape market to kill it. As an internal memorandum from one 3M executive stated, “I don’t want private-label 3M products to be successful in our office supply business, its distribution [channels] or with our consumers/end users.”20

A jury awarded damages of $68,486,697 (the amount after trebling) — almost 15% of the 3M Consumer and Office Business unit’s operating income in 2000. On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit concluded that rebate bundling, even if above cost,21 may exclude equally efficient rivals from offering product (in this case, tape). Thus, the bundled rebates were judged to be an exploitation of monopoly power by 3M. The appeals court ruled that there was sufficient evidence of predatory conduct under Section 2 of the Sherman Act and upheld the jury’s finding that 3M’s conduct violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act and Section 3 of the Clayton Antitrust Act. (See “A Primer on the Sherman Antitrust Act.”)

The lesson from 3M’s loss is that dominant marketers that use discounts to leverage market power from one product category to another are likely to violate the antitrust laws. Such discounts can be perceived as making it extremely difficult for competitors to obtain shelf space for their products or to implement promotions at the retail level.

Joint Marketing That Has Unintended Effects

A joint marketing program can become a problem for a dominant company. Companies may enter into these agreements because of the potential efficiencies of doing so, but the agreements can be extremely difficult to terminate where there is a size disparity between the collaborators. However, the problem is not with marketing jointly with another company in the first place; at issue is whether a program’s later cancellation has the purpose or effect of restraining price competition.23

The standard for rulings on such activities is the U.S. Supreme Court caseAspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp.24 Plaintiff Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp. owned one ski facility in Aspen, Colorado. The defendant owned the three remaining facilities in the area. At that time — the 1970s — the companies offered a joint marketing product, the “All-Aspen ticket,” which gave skiers from one resort access to the other three resorts without having to purchase additional tickets.

The ticket had been created at a time when numerous competitors operated the ski facilities at Aspen, but those competitors were being slowly acquired by Aspen Skiing Co. Aspen Skiing then discontinued the All-Aspen ticket, choosing to market a ticket that allowed access only between its own facilities and excluded access to the resort of its only remaining competitor, Aspen Highlands.

A jury found for the plaintiff under a monopolization theory, and Aspen Skiing was required to pay $7.5 million in damages —a huge sum for its industry in the 1980s. The verdict was upheld on appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court also upheld the jury’s verdict, noting that Aspen Skiing lacked a legitimate business justification for its decision to terminate the All-Aspen ticket.25 Perhaps equally important, the court noted that consumers were injured by the elimination of the ticket. A marketing expert for the plaintiff noted that skiers “are looking for a variety of skiing experiences, partly because they are going to be there for a week and they are going to get bored if they ski in one area for very long; and also they come with people of varying skills. They need some variety of slopes so that if they want to go out and ski the difficult areas, their spouses or their buddies who are just starting out skiing can go on the bunny hill or the not-so-difficult slopes.”26 The marketing expert also testified that consumers sought to ski all four mountains, and the abolition of the all-Aspen ticket made such an endeavor more difficult.

A recent Supreme Court decision involving a joint marketing initiative has describedAspen Skiing as at “the outer boundary” of antitrust liability.27 While the court’s recent decision inVerizon Communications Inc. v. Trinko limits the applicability ofAspen Skiing,28 it also sends the signal that if a company with market power terminates a joint marketing program without a legitimate business justification, that company risks incurring significant antitrust liability.

Promoting the Technology Contained in a Patent

Another possible violation of the Sherman Act involves the failure to disclose the holding of a patent while simultaneously promoting the technology contained in that patent to an organization responsible for setting industry standards. Typically, a private organization will promulgate voluntary consensus standards to promote common interfaces between substitute products; such voluntary consensus standards are usually then codified by both industry and government.

Simply interpreted, standards-setting can be pro-competitive. It may increase price competition, as it makes products easier for consumers to compare and contrast. It also allows for greater compatibility and interoperability, enabling suppliers “to compete in producing products and services related to the underlying standard technology.”29

However, the marketing of technology before a standards-setting organization was raised in the 2003 complaint by the Federal Trade Commission against the Union Oil Company of California. The FTC stated that Union Oil, or Unocal Corp., had subverted state regulatory standards-setting proceedings by making misrepresentations before the standards-setting body that were designed to enhance Unocal’s competitive position in the market.

The California Air Resources Board, or CARB, had initiated rule-making proceedings in the 1980s to establish regulations and set standards concerning low-emission, reformulated gas. Unocal had participated in the rule-making proceedings. The FTC alleged that Unocal monopolized, attempted to monopolize and engaged in unfair methods of competition.30 Unocal, anticipating that CARB would initiate rule making to regulate the properties of gasoline in California to reduce emissions, had devised a research project to determine the relationship between the various properties of gas and how they affect auto emissions. Unocal made several discoveries with respect to eight fuel properties and in the late 1980s filed patent applications covering their invention and discovery.

The point contended by the FTC was that Unocal shared the data with CARB, representing the information as nonproprietary and in the public domain, but when CARB adopted standards based upon the data, Unocal revealed its patent and sought royalties from its competitors. During the 1990s, a group of California refiners had been unsuccessful in a suit to invalidate Unocal’s patent, but in 2003, the FTC challenged Unocal’s conduct. The Commission asserted that Unocal had made its representations to CARB with the purpose of inducing “regulators to use information supplied by Unocal so that Unocal could realize the huge licensing income potential of its pending patent claims.”31 The case is currently before an administrative law judge.

New legislation — the Standards Development Organization Advancement Act of 2004 — protects standards-setting organizations from antitrust scrutiny to some degree (and from the threat of treble damages) by requiring the courts to consider the pro-competitive benefits of standards-setting activities. However, the act provides immunity only to the standards-setting organization itself; its members face full antitrust liability for their conduct. The driving principle is that the operations of standards-setting organizations pose unique opportunities for abuse of intellectual property. If the agency or court finds that such conduct violates the antitrust laws, the result could be that the patents cannot be enforced.32

Unocal is by no means the only company to have attempted such a strategy. A series of recent and well-publicized cases have found standards-setting participants liable for antitrust violations. Just one example: The FTC negotiated a consent decree with the computer company Dell Inc. concerning allegations substantially similar to those made in the Unocal case.33 The lesson is that marketing of patented technology to a standards-setting organization should be done with maximum openness.

Good-Citizenship Initiatives That Have Bad Ramifications

While our discussion thus far has emphasized market dominance by a single company and the perils of aggressive marketing tactics, antitrust exposure can likewise occur when companies act with benign intent in combining to dominate a market. It does not matter how obscure the circumstances or how worthy the rationale. Any manager might consider, for example, the surprise of the chancellor of the University of Wisconsin when, in the 2003–2004 academic year, his community initiative backfired. Concerned about the amount of alcohol drinking on and around the school’s Madison campus, the chancellor gathered local tavern owners together and asked for their help to solve the problem. The owners conferred and offered a solution: They would eliminate bargain-rate “happy hours” in an effort to reduce the level of alcohol consumption.

On the face of it, such a scenario deserves applause, since it was clearly intended to promote the common good. The legal perspective was quite different. Because the tavern owners effectively had collaborated to set new, higher prices for alcoholic drinks, their initiative was alleged to be a per se violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act by students who filed a lawsuit. Although the case was dismissed, the legal challenge itself had consequences. As one tavern owner put it, “It’s cost us so much money to defend this thing. Why does it cost so much to get a silly problem like this solved?”34

The tavern owners may have been fortunate. The Supreme Court has made it quite clear that good intentions do not matter in an antitrust case. “In applying the rules, the Court has consistently rejected the notion that naked restraints of trade are to be tolerated because they are well-intended or because they are allegedly developed to increase competition,” noted the court in the 1972 case ofU.S. v. Topco Associates Inc.35 In the University of Wisconsin case, allegedly the small businesses had collectively been able to act like a large business. Practically speaking, they now dominated their relevant market — defined as the sources of alcoholic beverages within a short radius of the Madison campus — and had effectively raised prices as a result of their collaboration.

Some Tactics for Balancing Competitiveness With Caution

The Sherman Act was designed in 1890 to prevent and restrain conduct that lacks any purpose other than the destruction of a competitor, the restriction of output, the increasing of price or the elimination of consumer choice. The law is increasingly being interpreted in ways that have a direct bearing on a range of marketing initiatives. The upshot for marketing managers, then, is to thoroughly re-evaluate each move to increase market share in terms of its potential to incur as many long-term risks as rewards.

As has been argued elsewhere, becoming No. 1 in market share is a sensible and worthy goal, and one that gets no argument from shareholders. For companies that sell through retailers, highest-share products are least likely to lose battles for shelf space. Also, businesses that purchase what others will consume are likeliest to select the “leading brand,” whether the buyer is an airline selecting packaged snacks or a hotel choosing audiovisual equipment.36

However, once leading-brand status has been achieved, it makes sense to consider the way in which antitrust evaluations are made and to rethink market share goals in light of the antitrust risks. Marketing managers often want to be evaluated based on market-share targets, because even in a shrinking product category they can raise share and perhaps qualify for bonuses despite a sales decline in absolute terms. However, for top management, gaining dominant market share should function like a blinking red light does to a driver — as an indication to stop and take a good look around. Issues deserving much more scrutiny include not only the way that goals are stated but also a range of marketing practices (either under way or contemplated) and a deeper awareness of antitrust risks among employees at all levels.

In considering marketing practices, it is useful to reiterate management’s obligation to juxtapose antitrust risks with the urge to compete successfully. Managers rarely believe that the conduct in which they are engaging is wrong, even when their company clearly dominates the market. Each competitor is viewed as a threat, and the reflexive response — supported by everything from compensation incentives to sales-force structure and marketing communications strategies — is to undercut the competitor rather than revisit alternatives such as raising the value of their own brand.

Such alternatives should be prompted at the strategic level of any company with one or more products that enjoy dominant share. Strategic approaches, such as line extensions as a method of gaining shelf space or brand extensions as a substitute for a focus on market share, need support at the highest levels; the mechanisms and corporate processes that underpin those approaches must be examined in detail in terms of their risks of breaching antitrust laws. If managers are evaluated only on share-point gains, they will naturally focus on such gains, especially if they have an overly narrow or outdated view of the risks of their approaches.

At a more tactical level, a renewed consideration of antitrust risk should prompt specific actions by managers of companies that enjoy dominant market share. Consider the example of a supplier that has been granted the category-captain role by a large retail chain. The appointment by that retailer of a “validator” — a competing supplier that in effect looks over the shoulder of the category manager — is common, although not universal. If the retailer does not make such an appointment, it would be prudent for the category-captain supplier to suggest such a role for one of its competitors. It is difficult to imagine that the actions that led to the decision inConwood would have taken place if Conwood employees had been reviewing the data associated with United States Tobacco’s category-captain decisions.

Another area for prevention involves formal and informal training in antitrust issues. The aim of such training should not be to make managers astute evaluators of what is illegal but to sensitize them to the fact that many actions they would consider “aggressive marketing” might now be interpreted as violations of antitrust laws. The potential for liability is enormous in dominant companies, as the cases previously highlighted have emphasized. In addition to substantial fines, possible legal remedies include divestiture of assets that are important in exploiting market power and conduct remedies that forbid engaging in certain practices. If there are good indications that managers have internalized that message, the training will have been worthwhile.

However, training will have fully met its objective only if employees demonstrate their awareness of what not to do by changing their behavior accordingly. How do they demonstrate that they werenot part of a closed-door meeting to fix prices? One anecdote from the oil sector is memorable. When the senior management of large international oil companies was entirely male, the attorneys at one major corporation gave this blunt advice in the effort to avoid any hint of price-fixing with competitors: “If you’re with any competitors and anybody starts talking about prices, you don’t just leave, you drop your pants first. We want everybody to remember that you left.” The company since has updated the advice for a world with female managers by suggesting, “Spill a cup of coffee as you’re leaving.”37

Another key question is more challenging: How do managers avoid writing memos and e-mails that may be used in court against their own company? Internal documents provide a clear threat if employees use them to demonstrate how vigorously they are attacking competitors. InConwood, the court saw considerable documentary evidence of predatory conduct.

The idea, of course, is not that managers should scale back on communicating. But they do need to think through what they communicateand what their subordinates communicate. Managers who think that damaging messages would never be sent or could not be recovered from e-mail are advised to look carefully at the evidence inConwood. Although courts typically discount marketing documents heavily because the documents tend to be overly exuberant and may not fully reflect company policy, such documents will not be discounted if the practices discussed in them have come to fruition or if they chronicle the effects of such policies.

IT IS IMPERATIVE TO emphasize the discussion of the roles that dominant companies play in a market38 and to understand the restrictions that the Sherman Act places on such roles. The examples cited in this article have, we hope, helped to bring home the issue of antitrust risk for managers whose competitive instincts and incentives have kept the issue in the background. It is encouraging to hear of some companies that already take the issue seriously enough to conduct annual antitrust audits, bringing in outside experts who train their managers and evaluate their marketing activities and results. Yet there is obviously much more to the issue than a training course or an evaluation exercise here and there.

Perhaps the most fundamental requirement is that managers begin to look at their competitive tactics — and at the business strategies and processes that support those tactics — through the eyes of antitrust regulators. By doing so, they can begin to understand that dominant share is what sparks scrutiny by enforcement agencies, however the agencies choose to define it. In the agencies’ view, it is typically not the mouse frolicking across the competitive field that is the problem — it is the elephant undaintily stomping everything in its path. It is far better for managers to hear that message from outside experts or from their own attorneys than from a federal judge.

References

1. For example, the FTC challenged Toys “R” Us’s practice of threatening not to sell the products of toy vendors that sold the same products to discount warehouses. In other words, Toys “R” Us wanted to be the exclusive retailer of new and exciting toys. See 126 F.T.C. 415 (1978), aff’d,Toys “R” Us Inc. v. Federal Trade Commission, 221 F. 3d 928 (7th Cir. 2000). See also R. Steiner, “Category Management — A Pervasive, New Vertical/Horizontal Format,” Antitrust 15, no. 2 (2001): 77–81.

2. D. Balto, “Ten Developments in the Antitrust Treatment of Category,” chap. 6 in “Course Handbook, 44th Annual Advanced Antitrust Seminar: Distribution & Marketing” (New York: Practising Law Institute, 2005).

3. See FTC, “Report on the Federal Trade Commission Workshop on Slotting Allowances and Other Marketing Practices in the Grocery Industry,” February, 2001, www.ftc.gov/bc/slotting/.

4. See, e.g., M.L. Kovner and C.R. Kass, “Monopolies Take a Hit: Be Careful With Smaller Competitors or They May Come Back to Haunt You,” Marketing Management (September–October 2003): 48–50; D. Desrochers, G. Gundlach and A. Foer, “Analysis of Antitrust Challenges to Category Captain Arrangments,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 22 (fall 2003): 201–215; R. Steiner, “Category Management — A Pervasive, New Vertical/Horizontal Format,” Antitrust 15, no. 2 (2001): 77–81; K. Glazer, B. Henry, and J. Jacobson, “Antitrust Implications of Category Management: Resolving the Horizontal/Vertical Characterization Debate,” Antitrust Source (July 2004), www.abanet.org/antitrust/source/july04.html.

5. Certain types of agreements almost always increase price or restrict output, such as agreements to bid-rig, divide markets, etc. For those types of conduct, the “courts conclusively presume such agreements, once identified, to be illegal, without inquiring into their claimed business purposes, anticompetitive harms, pro-competitive benefits, or overall competitive effects.” See FTC and U.S. Department of Justice, “Antitrust Guidelines for Collaborations Among Competitors,” April 2000, www.ftc.gov/os/2000/04/index.htm#7, 3.

6. Section 2 of the Sherman Act, which forbids monopolization, attempts to monopolize and conspiracies to monopolize, appears to be divided along this analytical regime. See M.B. Roszkowski and R. Brubaker, “Attempted Monopolization: Reuniting a Doctrine Divorced From Its Criminal Law Roots and the Policy of the Sherman Act,” Marquette Law Review 73 (1990): 355–420.

7. The more egregious the conduct, the easier it likely will be to persuade courts to go with narrow market definitions. One way is to suggest that the defendant’s conduct is often an indicator of the market intended to be monopolized or restrained. The more egregious the conduct, the better the indication that the defendant considers the product or geographic area a “market” that can be monopolized or restrained.

8. The antitrust enforcement agencies use the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index to determine market concentration. The HHI is the sum of the squared shares that each market participant possesses in the identified relevant market. See Department of Justice and the FTC, “Horizontal Merger Guidelines” (Washington, D.C.: FTC, 1992), Section 1.5.

9. An example from an antitrust course is helpful. In Industry X, suppose there are five equally sized companies, each controlling 20% of the market. 202 + 202 + 202 + 202 + 202 = 2,000 HHI. In Industry Y, suppose there is one company with 60% of the market, and the rest are relatively small. 602 + 102 + 52 + 52 + 52 + 52 + 52 + 52 = 3,850 HHI. A traditional measure of concentration (the four-company concentration ratio known as “CR4”) would indicate that the first market is equally as troublesome as the second (CR4 would equal 80 in both). The HHI, however, indicates that the second market is far more troublesome.

10. One other recent example includes Nestlé SA’s 2001 acquisition of Ralston Purina Co.

11. D. Desrocher, G. Gundlach and A. Foer, “Analysis of Antitrust Challenges to Category Captain Arrangments,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 22 (fall 2003): 201–215.

12.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 290 F. 3d 768 (6th Cir. 2002).

13.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 774.

14.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 773.

15.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 785.

16.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 773.

17.Conwood Co. v. United States Tobacco Co., 537 U.S. 1148 (2003).

18.LePage’s Inc. v. 3M Co., 324 F. 3d 141 (3d. Cir. 2003).

19. Sam’s Club stood to gain $264,000 and Kmart Corp. stood to gain $450,000.LePage’s Inc. v. 3M Co., 154.

20.LePage’s Inc. v. 3M Co., 164.

21. A company with monopoly power that prices below incremental cost with a dangerous probability of recouping its investment in below-cost prices may be liable under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. SeeBrooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 113 Sup. Ct. 2578 (1993). However, plaintiffs typically do not meet with success on such a theory.

22. Section 3 of the Clayton Act, Title 15, prohibits in part leases, sales or contracts for commodities where the contract may “substantially lessen competition” or “tend to create a monopoly.” Exclusive dealing arrangements may potentially fall into this category.

23. FTC and U.S. Department of Justice, “Antitrust Guidelines for Collaborations Among Competitors,” in J. Flynn, H. First, and D. Bush, “Antitrust: Statutes, Treaties, Regulations, Guidelines, Policies,” 2005–2006 ed. (New York: Foundation Press, 2004), 136.

24.Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585 (1985).

25.Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 608–609.

26.Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 606 n.34.

27.Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 124 Sup. Ct. 872, 879 (2004).

28.Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko LLP, 872.

29. See D. Balto, “Standard Setting in a Network Economy” (presentation at Cutting Edge Antitrust Law Seminars International, New York, Feb. 17, 2000); see also C.E. Handler and J. Brew, “The Application of Antitrust Rules to Standards in the Information Industries — Anomaly or Necessity?” Computer Lawyer 1, no. 11 (1997): 14.

30. SeeIn the matter of Union Oil Company of California, Docket No. 9305, www.ftc.gov/os/2003/03/unocalcmp.htm.

31. Ibid.

32. See Dell Computer Corp., 121 FTC 616 (1996).

33. Ibid.

34. R. Foley, “Price-Fixing Suit Against Bars Dismissed. 24 Bars Were Not Conspiring in Banning Weekend Drink Specials, Judge Rules,” St. Paul Pioneer Press (Minnesota), Apr. 8, 2005, p. B2.

35.U.S. v. Topco Associates, 405 U.S. 596, 610 (1972).

36. B. Gelb, “Why Rich Brands Get Richer, and What to Do About It,” Business Horizons 35 (September–October 1992): 43–46.

37. Author’s interview with Richard Mullineaux, Shell USA (retired), Sept. 19, 2004.

38. M.L. Kovner and C.R. Kass, “Monopolies Take a Hit: Be Careful With Smaller Competitors or They May Come Back to Haunt You,”Marketing Management (September–October 2003): 48–50.