When One Size Does Not Fit All

As a business diversifies, it may need more than one supply chain. Here’s how Dell addressed that challenge.

Dell created a new organization to manage the transition to four supply chains, each focused on a different customer segment.

Image courtesy of Dell.

Most operations strategies focus on either efficiency, sometimes referred to as a push strategy, or responsiveness, sometimes called a pull strategy. Either the company seeks operational efficiency and tries to hold down costs across all functional areas, or it focuses on responsiveness and tries to ratchet up speed, order fulfillment and service levels.

Although seasoned operations and supply chain executives understand the difference between efficiency and responsiveness, many are confused about when to apply each strategy. In recent years, more and more companies have been caught in the bind in which Dell Inc. found itself in 2008, when it realized that the highly responsive configure-to-order supply chain that had made its online store the world’s largest channel for personal computers sales no longer fit the needs of some of its fastest-growing businesses: its new physical retail channel, its enterprise sales or even its high-volume consumer products. Facing increased pressure from emerging and revitalized competitors, Dell found that its long-vaunted supply chain was no longer right for all aspects of its business.

In 2008, for example, when Dell entered the retail channel, the company tried to use the same supply chain as its online configure-to-order business. But competition in conventional retail can be more price-sensitive than it is online, and the supply chain Dell designed for online was not optimized for lowest cost. By contrast, what was valued most online — the customer experience associated with the ability to configure the product to exactly what the customer wants — was not needed in the store as most retail orders are large and focused on fewer configurations.

Adding to the challenge, the company faced corporate and public sector clients who were increasingly looking for a complete solution for their IT needs, and in many cases, a solution designed specifically for their organization. This again entails a supply chain strategy quite different from the one employed for online customers.

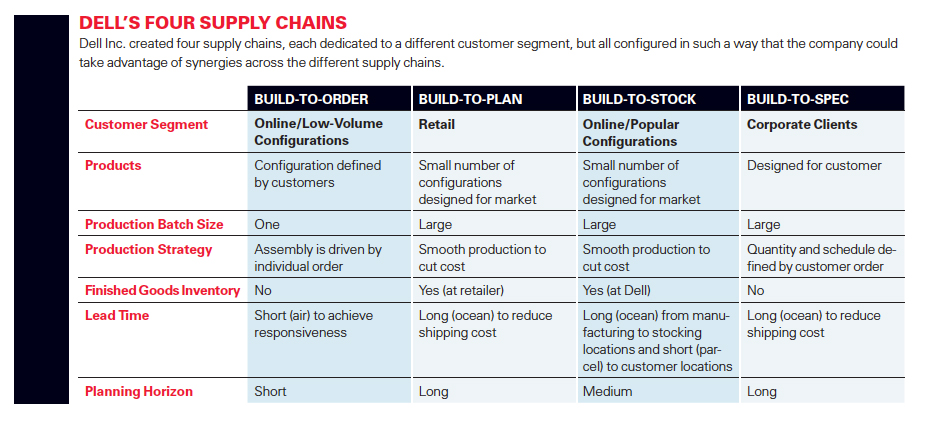

Clearly, Dell needed to transform its supply chain to serve new customers in new channels with new types of products. The question was: how to do that effectively? Dell decided to create multiple supply chains, each dedicated to a different segment of the PC industry, but configured in such a way that the company could take advantage of synergies to reduce complexity and benefit from economies of scale.

We understood that any framework for supply chain segmentation must take into account demand uncertainty, cost drivers, relationships with customers, the customer value proposition and technology clock-speed — the speed by which technology and product change in a particular industry.

Earlier research by one of the authors, described in the book Operations Rules by David Simchi-Levi, suggested that a good first step is to focus on demand uncertainty and customer relationships. These dimensions determine the various customer segments, each of which requires a different supply chain strategy.

For example, the supply chain strategy that Dell should employ when demand uncertainty is high and the relationship with the customer is loose must be different from the strategy that it should apply when demand uncertainty is low and the relationship is tight. By reflecting on these two dimensions, we realized Dell needed to roll out all four of the most basic kinds of supply chains, which we’ll call Build-to-Order, Build-to-Plan, Build-to-Stock and Build-to-Spec. (See “Dell’s Four Supply Chains.”)

When the relationship between a company and its customers is loose and demand uncertainty is high, the supply chain needs to be managed based on realized demand, or a pull strategy. This is exactly the strategy that Dell employs in its traditional business. Online, Dell offers millions of possible configurations, and as a result, forecast accuracy by configuration is poor and volume by configuration is low. As Dell offers to satisfy consumers’ individual needs, the focus is on higher margins, and thus the cost of a lost sale is high. Here Dell employs a Build-to-Order strategy, where component inventory is managed based on forecast while actual customer requirements determine the final configurations.

When Dell entered the retail business in early 2008, it realized this was a different type of business. The number of configurations sold is low, with few customization options, so forecast accuracy and volume by configuration are much higher than for online sales. Finally, because competition in retail is more price-sensitive, the cost of a lost sale is lower than in the online channel.

The retail segment, therefore, is associated with low demand uncertainty and a loose customer relationship, making a traditional push-based strategy better because managing the supply chain based on long-term forecast lowers cost through economies of scale (high volume) and forecast accuracy (low demand uncertainty). In this Build-to-Plan strategy, procurement, production and shipment decisions are all based on forecast.

Interestingly, Dell identified another customer segment with low demand uncertainty and loose customer relationships: popular products sold online. By nature, the volume and forecast accuracy are high for these products, and as a result, call for a push-based strategy, or what Dell refers to as a Build-to-Stock strategy. In this supply chain, popular product configurations are prepositioned in the network, based on long-term forecasts, to provide a very aggressive response time, such as next-day shipment. In this hybrid push-pull strategy, procurement, production and shipping to stocking points are all based on forecast, while shipment to customer locations is based on realized demand.

Finally, we found another segment where demand uncertainty is low and the relationship with customers is tight: enterprise clients. In this case, the design and product variety are customized for individual corporations. The menu of options offered to corporate clients has a longer product lifecycle, with more overlap across generations of technology. This enables corporate clients to order the same configuration over a long period of time and lower their total cost of ownership. Because the relationship between Dell and its corporate clients is tight, forecast accuracy and volume are high. This is quite different from the characteristics of individual consumers. Thus, for corporate clients, Dell applies a strategy referred to as Build-to-Spec. Dell commits to a short response time and high menu configurations and does not keep finished goods inventory. Products are assembled to order using components ordered well ahead of time, based on forecast.

Synergies Across Supply Chain Segments

An important challenge in supply chain segmentation is using synergies across different supply chains to reduce complexity and exploit economies of scale. In general, there are five possible areas that can yield synergies: procurement, product design, manufacturing, planning and order fulfillment.

Synergies in procurement imply leveraging volume across the various segments to reduce purchasing costs. Strategies for product design synergies emphasize using standard components across all the supply chains and reducing product portfolio. Manufacturing synergies demand the consolidation of as much manufacturing infrastructure as possible. As a result, there is a need for a single process to allocate manufacturing capacity to the different segments. This is sales and operations planning (S&OP) — one process applied across all supply chain segments to align demand, supply and inventory and to allocate production capacity to the various supply chains based on actual and forecast demand.

Dell takes advantage of synergies in order fulfillment for the North American supply chain by using one infrastructure for all four supply chains. For example, the company has U.S. fulfillment nodes in cities such as Los Angeles and Chicago — and employs some of them in more than one supply chain. In the online business, where speed is critical, items are air shipped from manufacturing in Asia to four locations in the U.S.: Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles and New York, and from there by parcel to customer locations. Retail is different. Because cost is the focus of the Build-to-Plan supply chain strategy, products are shipped by ocean to Los Angeles and Chicago, and from there, by truck to the retailers. Then, in the Build-to-Stock strategy applied to popular products sold online, items are shipped by ocean to North America and then trucked to two key locations, Los Angeles and Nashville, for shipping to individual consumers. The result is a simple logistics network that still meets the needs of a complex business.

As simple as it sounds, executing this design was not easy. The first step was creating an organization to manage the entire transformation. This organization focused on every aspect of Dell’s business, from product design through manufacturing and transportation all the way to customer care, warranty and technical support.

Very quickly the team made a critical decision: to shift more manufacturing activities from internal operations to the supply base, thus utilizing the manufacturing capabilities of its partners across its global manufacturing network. This was a huge change in cost structure, from fixed cost to variable cost, resulting in a significant savings to the bottom line.

Next, the team undertook a comprehensive transformation of the legacy IT infrastructure that supported Dell’s configure-to-order strategy, in which lot sizes do not exist. With the implementation of customer segmentation, some segments, for example retail, require the technology to support large lot sizes and imply the existence of finished goods inventory, something Dell had never considered before. As a result, the company needed to rethink its IT infrastructure so it could support multiple channels.

The final phase was the customer segmentation. Dell mined billions of customer transactions to segment different customer types based on their customer value propositions. This allowed the company to simplify its product lines and market the most popular configurations. This simplification reduced costs and improved responsiveness through improved forecast accuracy. It also enabled the company to identify popular products which are good candidates to be produced in advance, prepositioned in the network and offered online to consumers, thus enabling Dell to respond quickly to consumer demand.

The second step in this phase involved implementing the four different manufacturing and operations strategies. Each is associated with a different segment: Build-to-Order is the strategy Dell still employs for the low-volume configurations in the online business. Build-to-Plan is a strategy the company is now using for the retail channel. Build-to-Stock is used for the popular products sold online. Finally, Build-to-Spec is applied for corporate clients.

Since this project started three years ago, the transformation in Dell’s business has been substantial. Product availability has improved 37%, and order-to-delivery times are 33% shorter. Dell now offers significantly fewer configurations, and as a result, forecast accuracy has improved dramatically, by a factor of three. The effective matching of transportation mode with supply chain segment led to a staggering 30% reduction in freight cost for notebooks and slashed manufacturing cost by 30%.

Dell’s situation is not unique. Indeed, many global companies underperform because of a mismatch between business needs and supply chain configuration. But not for long. Customer-driven supply chain segmentation is increasingly necessary to compete in today’s global economy. In coming years, more and more companies will need to create flexible supply chain strategies to deliver competitive value propositions.

Comments (6)

Do You Really Need Multiple Distribution Channels?

Leanne Huang

Geetsikha Pathak

Geetsikha Pathak

Nidal Dwaikat

Jens Claassen