How Would-Be Category Kings Become Commoners

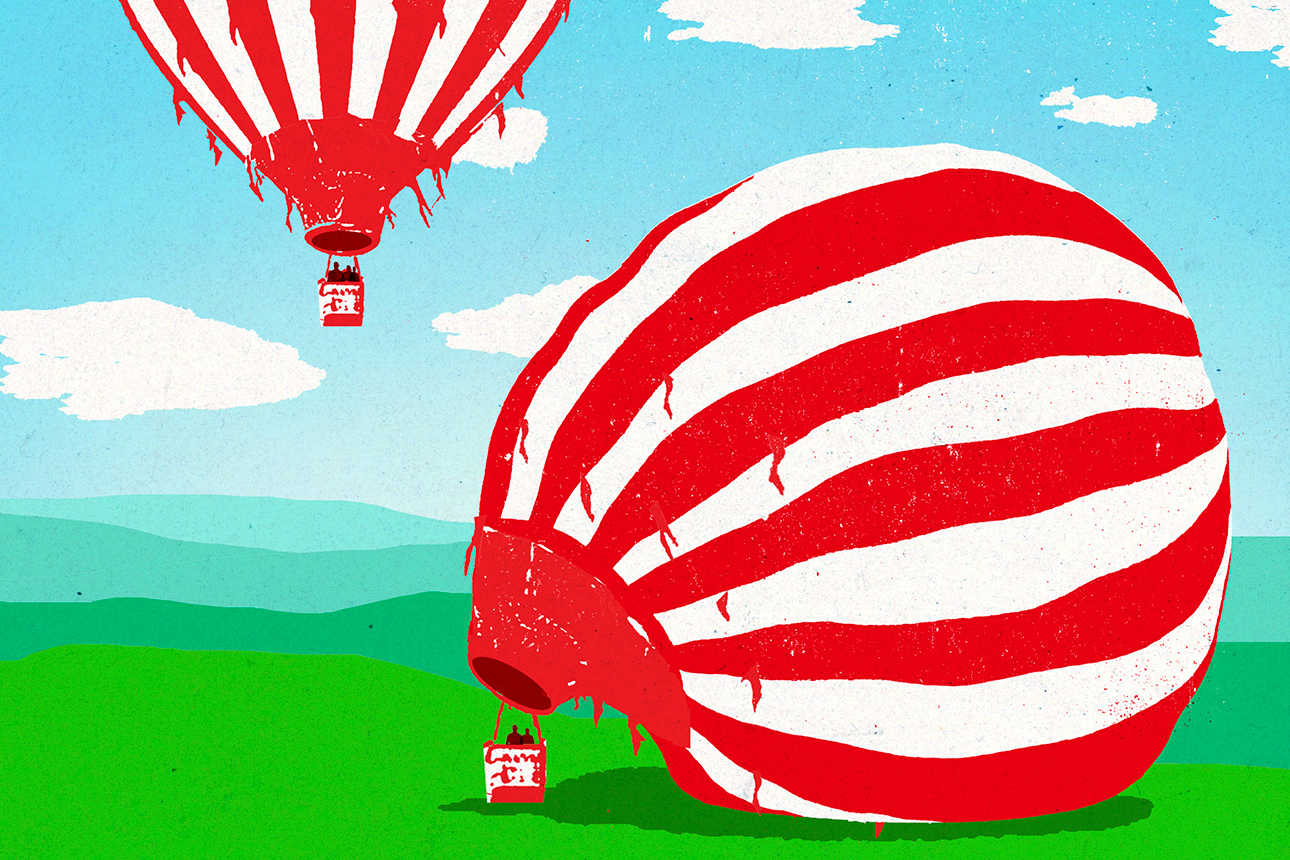

Innovative companies may succeed in pioneering new markets, but often fail to dominate the categories they create.

Image courtesy of Richard Mia/theispot.com

Starting any business is hard, but creating a new category of business with a completely new model is a high-wire act. Companies have to convince investors, customers, the media, analysts, and others that something the world has long managed without is now a necessity and legitimately constitutes a new business category. While educating and selling the market on this new category, there’s also a business to build and a whole new business model to formulate. Pulling this off is like delivering a nonstop TED Talk while inventing the light bulb and building General Electric all at the same time.

Many people feel it’s a challenge worth taking. Category creation is the holy grail in business. Companies that succeed at creating entirely new markets, industries, or product categories — like Airbnb, DocuSign, and Salesforce — generate wealth beyond their founders’ wildest dreams. The spoils are so great that the winners are often referred to as category kings. Over time, their brand name becomes virtually synonymous with their category, effectively barring new entrants.

Once a king emerges, would-be competitors become also-rans, or commoners. These businesses find it increasingly hard to maintain support: Media and analyst attention dries up, leading to less investment and fewer customers. Ultimately, they are sold for parts or shut down altogether, like Napster or AltaVista.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Getting this high-wire act right is critical. Competition in new categories is more intense than ever. The cost of starting a digital company has shrunk by 90% in the two decades since the dot-com crash, thanks to the emergence of open-source software, cheap cloud computing, and social media platforms that offer low-cost advertising and free publicity.1 Low startup costs mean more startups, more categories, and more competitors vying for consumers’ limited attention. For example, shortly after Beyond Meat emerged, Impossible Foods, Hungry Planet, and a half-dozen other startups were offering plant-based meat and dairy products — all seeking to become king of the category.

Information overload makes it hard to get people’s attention. And while social media offers a cheap way to reach consumers, it’s increasingly difficult to keep their interest. Some pioneers of new categories assume that they should spend much of their time hyping products at trade shows and meeting with journalists and analysts. Many spend significant sums each year on marketing. Even those who are selling products with self-evident technical and economic benefits still spend enormous energy trying to convince audiences that they need this new thing and should choose their company to provide it.

It’s typically during this aggressive marketing-and-category-creation stage that we see companies lose their way. We have come to think of this phenomenon as the Commoner’s Curse: A prominent high-flying company succeeds at building a lucrative new category only to end up handing the keys to the kingdom to someone else. To understand how would-be kings wind up as commoners, we have spent several years studying companies pioneering new categories; interviewing hundreds of entrepreneurs, corporate innovation chiefs, market analysts, and journalists; and poring over years’ worth of press releases and media stories.2 We discovered that many executives undermine their own ventures’ standing during the category-creation phase by misinterpreting data and misfiring on strategies deemed fundamental to creating new categories.

Some self-destruct by ruthlessly and indiscriminately attacking incumbents. Others, in an effort to win legitimacy, funding, and early media and customer support, focus too much on promotions and too little on product development. Still others, in an effort to gain traction, adopt trendy labels that later limit their ability to articulate their unique value proposition and ultimately lose control of their strategy.

Over the years, we’ve seen very promising companies end up on the sidelines of categories they helped create — all because of three common and easily avoidable mistakes.

Mistake No. 1: Sloppy Attacks on the Establishment

In their fervor to identify themselves in opposition to the status quo, category creators sometimes aggressively discredit opponents early on. It’s an approach that can easily backfire, especially if they strike the wrong tone or attack those opponents indiscriminately. For instance, on the day Microsoft launched its competing team-chat product in 2016, Slack ran a full-page ad in The New York Times welcoming Microsoft to the category and offering “friendly” advice on how to build a good communications app.3 The stunt generated plenty of press, as intended, but much of it was unwelcome. Normally supportive media outlets characterized Slack’s ad as petty, disingenuous, and self-congratulatory, and some even accused the company of making misleading product claims. Reporters pointed out that Microsoft, which was integrating its app with its productivity tools, had a huge advantage, and they questioned whether companies should still pay extra for Slack. Soon thereafter, Facebook and Google entered the category. Although it’s premature to label Slack a commoner, the war of words launched four years ago served mainly to alienate members of the press and likely aroused sleeping giants.

There’s nothing wrong with going on the attack. Pointing out industry shortcomings is often necessary to challenge the status quo, as Salesforce has demonstrated over the years by calling rivals IBM, Oracle, and SAP dinosaurs. The trouble arises when companies attack in a sloppy and scattershot way. Two fintechs we studied in a nascent social-investing category illustrate the point. Early on, both devoted huge amounts of money and managerial time to public outreach. The goal was to sell the public on a new kind of social-investment platform. To capture attention, these leaders disparaged the entire investment industry as esoteric and old guard — saying it forced clients to pay pricey experts when they could instead rely on knowledgeable nonprofessionals for investing advice.

The news media bought into the appealing underdog tale, and the social-investing category took off.

But the targets of these scattershot attacks — money managers, financial advisers, brokerages, investment gurus, hedge funds, and even the financial press — eventually struck back. Some took umbrage at the wholesale labeling of industry investment professionals as crooks. Bloomberg, perhaps unsurprisingly, dismissed one such site as an “upstart” and let analysts take potshots. “I think the website is well intentioned in concept but is full of misstatements, bogus statements, and statements that investors beat the market if they tag along with smart people,” wrote one analyst, adding that fraudsters could use the site and that it could undermine reputable advisers. He also complained that the website “makes financial advisers out to look like crooks trying to take advantage of the innocent public.”4

Soon, other market observers were questioning the entire conceit. How wise was it, really, to share precious stock tips with the masses? The financial press, which had been largely supportive early on, turned negative, savaging both brands. Meanwhile, lower-profile competitors swooped in to scoop up the spoils — much to the irritation of the category’s other contributors.

“We were irked that all of the PR we’d generated gave free shout-outs to the others,” a vice president at one of the two category pioneers told us in an interview. “We earned that press; why are they getting to free-ride?”

Some critics of the two high-profile companies, mindful of the category’s potential, invested in the less aggressive and less visible social-investing startups. In the end, several companies that had helped build the new category were sold (losing investors’ money) and those waiting in the wings stepped in.

Our research shows that a subtler, more deliberate approach often works best. The successful fintechs we studied postponed their attacks, letting peer-competitors strike first and suffer the backlash. Successful kings also forge oppositional identities and challenge the status quo, but attacks are typically less petulant and more measured. Some, for example, go after inanimate targets that can’t strike back, such as waste and outdated ways of doing things. For instance, Kevin Plank of Under Armour, a maker of innovative sportswear, proclaimed cotton to be the enemy; Keith Krach at DocuSign, the electronic-signature category king, took aim at paper waste. By evading threats to the nascent brands, over time these companies enjoy greater audience support and are more likely to emerge as category kings.

Mistake No. 2: Promoting the Category Without Refining the Job

Another mistake that category commoners typically make is to spend too much time and money promoting the new category while failing to come to grips with the “jobs” that consumers would actually “hire” their products or services to do.5 Entrepreneurs in new categories need to raise money, legitimize the market, and attract customers. But some get carried away with extolling the virtues of their product. In category creation, drumming up early publicity can quickly become a full-time occupation. It’s easy to see how this happens. It’s seductive and fun to be in the limelight, chatting with reporters and speaking on panels. But product development — and customers — can take a back seat when founders become conference fixtures and media darlings. Our research shows that many promising entrepreneurs make this mistake. As a result, their goals get subverted.

Color Labs is a prime example of a company that put promotion before product. Bill Nguyen, who had previously sold a company to Apple, and his experienced cofounders raised $41 million without testing their idea with the public or even launching an app. They did so by hyping the product. Nguyen boasted to journalists that the social photo-sharing app would be a “Facebook killer.”6 The idea was that people would go to a cafe, museum, or park, take a photo, and post it on Color. Others nearby would do the same, and thus strangers could connect. But when the app launched in 2011, it was buggy and the site was eerily quiet. Negative reviews in Apple’s App Store called Color confusing and pointless. Eventually, the business shut down. Commentators later pointed out that Color Labs tanked not just because it failed to provide a satisfactory solution to a job to be done, but because the job it identified didn’t actually need to be done.7 People weren’t dying to find ways to connect with strangers in the moment.

Digg is another cautionary tale. In 2004, Digg launched as a link aggregator website. According to cofounder Kevin Rose, Digg would displace newspapers with a new kind of digital front page. Users would vote on stories, determining which articles others would see. It was an interesting concept — letting users, not editors, decide on story placement — and one that persists today, including in Facebook’s news feeds. Investors and journalists loved Rose and his disruptive tale. In 2006, BusinessWeek put the twentysomething on its cover, treating him as a wunderkind. Soon, though, generating traffic and buzz took priority over building community. A shortcoming of this strategy became apparent in 2010, with the rushed release of a new version designed to chase mainstream consumers instead of satisfying Digg’s loyal user base.8 Visits soon dropped by more than half, 40% of the staff had to be laid off, and Rose resigned.9 The media may have loved Rose, but customers didn’t want to hire his latest product version, and many of them moved to Reddit, a smaller competitor that had incorporated many of Digg’s original features. Ultimately, Rose succeeded at creating a new category that other companies would lead.

In contrast, WhatsApp avoided early category promotion altogether. Instead of hyping the market, cofounder Jan Koum quietly launched a product just one month after starting the business. Lack of visibility proved fortunate, since early versions kept crashing. As the app gained traction, Koum and cofounder Brian Acton continued to avoid the spotlight, steering clear of the press (and even investors) and working from an unmarked building in Mountain View, California. In a media profile in April 2014, Koum said they were more interested in building stuff than in talking about it and added that word-of-mouth endorsements from users were far more valuable than the media’s imprimatur.10 This profile, and others like it, appeared only after Facebook had acquired the company for $19 billion. By then it had created a new mobile-messaging category and become one of the world’s most popular phone apps.

This is not to say that promotions and marketing don’t matter. Without them, categories wouldn’t exist. The key, we’ve learned, is to view communication more broadly. Salesforce founder Marc Benioff, known for always having time for reporters, says it was communication with customers (not the media) that shaped his company from the beginning. From its earliest days, customers and prospects were invited to take a look at what the company was working on, test out products, and offer feedback. The feedback was used to better align products with the jobs that customers were trying to get done. Keeping the lines of communication open with customers and putting the job first continues to drive Salesforce’s growth today.11

Mistake No. 3: Embracing Trendy but Flawed Market Labels

Interested observers, such as media and analysts, are prone to inventing labels to describe new market categories. “Fantasy investing” and “social investing” were popular labels we encountered while researching a new category of fintechs. Routinely, such labels are shorthand analogies to high-profile brands: A company might be called “the Facebook of investing” or “Uber for lawyers.”

Far too often, though, pioneers — to legitimize their new category and to gain traction with audiences — embrace these trendy labels even when they’re not entirely accurate.

Thousands of entrepreneurs have used the “Uber for ____” label in pitch decks, including the Uber for makeup, laundry, private jets, ice cream, and medical marijuana.12 Occasionally, these descriptions accurately capture startups in emerging categories; usually, they don’t.

Some entrepreneurs even adopt these glib analogies in external communication. The trouble arises when it’s obvious that the label doesn’t accurately describe the business — or, worse, when it once did, but the original strategy isn’t working anymore and the business must pivot to a different (and probably less sexy) model to compete. Alas, now the company is trapped: Audiences remain firmly committed to the company identity sold to them by the founders — one that no longer applies. Meanwhile, competitors that resisted trendy labels are freer to switch to more promising models.

SoundCloud, an early music-sharing platform, embraced the externally imposed label “a YouTube for audio.” Initially, when the company was hosting underground and amateur artists who published their work, this formulation was helpful. But later, when it moved mainstream by targeting high-profile artists and adding a monthly subscription service, customers attracted by the original rebel image fled. Plagued by that problem and others, such as rights issues, mismanagement, and heavy losses, in 2017 the company laid off 40% of its workforce and shuttered offices in San Francisco and London.13

The fundamental risk of embracing glib labels early on, particularly in new categories, is that the strategy, the offering, or both usually need revising. Indeed, SoundCloud has since returned to its roots of attracting original content creators, such as indie artists and podcasters, with new software tools for uploading, sharing, and promoting content. But the company’s bumpy ride illustrates how embracing labels too soon can make it difficult to experiment and pivot. Leaders often cling to labels that have captivated audiences — or worse, they alter their own product-market strategies based on those labels long after it’s clear that they conflict with what the company should be doing.

Other commoner companies make the mistake of embracing a label that becomes passé and stigmatizes an entire category whose component companies become standard-bearers for dated ideas. Being a “daily deal” company suited Groupon (and the startups that emerged in its wake) until that business fad faded and vouchers became yesterday’s news. As revenues have declined, the company has worked to move away from its discount-coupon voucher business and has struggled to achieve results approaching those of its giddier days.14

Our research suggests a more productive way forward. Companies that reject observer-imposed labels (and the lure of easy comprehensibility) may sacrifice early media coverage but will ultimately maintain more control of their images, company narratives, and strategies. Then again, Ethan Brown, the founder of Beyond Meat, has managed to get plenty of attention while rejecting observers’ labels. He routinely challenges those who lump his business into the “fake meat” category: A car isn’t a fake horse-drawn carriage, he asserts, nor is Beyond Meat’s product an alternate chicken. Cars took horses out of the equation, he points out.15 Brown’s goal is to become mainstream by supplanting meat with plant-based protein, which, like meat, is made of amino acids, lipids, trace minerals, vitamins, and water.

By sticking with their own labels and stories, innovators resist abdicating strategy to outsiders. Thanks to the efforts of Brown and others, the press now routinely refers to Beyond Meat’s category as “vegan meat brands” and to traditional meat products as “animal-based meat.” Indeed, Brown has fought successfully to sell his product to mainstream consumers, at fast-food chains, and alongside beef and chicken in grocery stores instead of in more specialized, less popular vegan sections.

Category kings aren’t necessarily the first to market, the boldest, or even the most innovative companies. But those we’ve studied typically navigate the category-creation process in a distinctive way. They’re content to let others attack the establishment, including industry incumbents, early on and to devote their own time and resources into carefully defining the category. They attack, too, but in their own good time, often selecting targets that can’t strike back. They sacrifice early press while they fine-tune their solutions — products that customers will actually hire to do a job. And they reject trendy category labels that could lock them into undesirable models later. Ultimately, these companies, by taking a more systematic and measured approach, enjoy greater visibility and more favorable audience support than their peers. Then, when the early darlings become cautionary tales, the true kings step in to seize the throne.

References

1. R. McDonald, A. Burke, E. Franking, et al., “Floodgate: On the Hunt for Thunder Lizards,” Harvard Business School case no. 617-044 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2017).

2. R. McDonald, “Category Kings or Commoners? Market-Shaping and Its Consequences in Nascent Categories,” working paper 16-095, Harvard Business School, Boston, January 2020.

3. The Slack ad is reminiscent of Apple’s 1981 ad in The Wall Street Journal welcoming IBM to the personal computer market.

4. “Website to Rank Financial Advisers on Investment Results,” Bloomberg, Oct. 8, 2007, www.investmentnews.com.

5. Clayton Christensen first articulated this simple but game-changing insight in 2005, when he explained that although business leaders knew more about their customers than ever before — thanks to big data and sophisticated analysis tools — they were misunderstanding why people make purchases. They assumed that people buy things because they fit a particular demographic or psychographic profile when in reality people “hire” products to help them make progress in the circumstances in which they find themselves. See C.M. Christensen, T. Hall, K. Dillon, et al., “Know Your Customers’ ‘Jobs to Be Done,’” Harvard Business Review 94, no. 9 (September 2016): 54-62.

6. D. Sacks, “Bill Nguyen: The Boy in the Bubble,” Fast Company, Oct. 19, 2011, www.fastcompany.com.

7. E. Lee, “Why Did Color Labs Fail?” Collapsed, Aug. 15, 2017, https://collapsed.co.

8. D. Thier, “Digg Founder Kevin Rose Takes to Reddit, Talks Regrets,” Forbes, Aug. 2, 2012, www.forbes.com.

9. RaphaelM, “5 Things You Need to Know About the Rise and Fall of Digg.com,” Harvard Business School Digital Initiative, Nov. 18, 2016, https://digital.hbs.edu.

10. D. Rowan, “The Inside Story of Jan Koum and How Facebook Bought WhatsApp,” Wired, May 1, 2018, www.wired.co.uk.

11. C. Gallo, “Storytelling Tips from Salesforce’s Marc Benioff,” Bloomberg, Nov. 3, 2009, www.bloomberg.com.

12. A. Webb, “The ‘Uber for X’ Fad Will Pass Because Only Uber Is Uber,” Wired, Dec. 9, 2016, www.wired.com.

13. R. Mac, “The Inside Story of SoundCloud’s Collapse,” BuzzFeed News, July 28, 2017, www.buzzfeednews.com.

14. L. Sanchez, “Groupon’s Evolving Business Strategy,” The Motley Fool, March 19, 2019, www.fool.com.

15. L. Darmiento, “Ethan Brown Went Vegan but Missed Fast Food. So He Started a Revolution,” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 10, 2020, www.latimes.com; and S. Brownstone, “Can Silicon Valley Make Fake Meat and Eggs That Don’t Suck?” Mother Jones, Dec. 2, 2013, www.motherjones.com.