Mastering Strategic Movement at Palm

Topics

Why do some companies succeed in defeating stronger rivals while others fail? All ambitious businesses must face that question sooner or later. Whether you’re a startup taking on industry giants or a giant moving into markets dominated by powerful incumbents, the basic problem remains the same: How do you compete with opponents who have size, strength and history on their side?

The answer lies in a simple but powerful precept: Successful challengers use what we call judo strategy to prevent opponents from bringing their full strength into play.1 Judo strategists avoid head-to-head struggles and other trials of strength that they are likely to lose. Instead, by relying on speed, agility and creative thinking, they develop strategies that make it difficult for stronger rivals to compete.

Palm Computing (now Palm Inc.) provides a powerful illustration of judo strategy at work. Founded in 1992 by Jeff Hawkins, Palm dominated the hand-held computing market less than a year after shipping its first electronic organizer in early 1996. Even more remarkably, despite competition from the most powerful software company in the world, Palm went from strength to strength. Microsoft Corp. marshaled masses of money, manpower and marketing muscle behind its own hand-held operating system. But year after year, Palm remained far ahead. And when it went public in March 2000, first-day trading valued the company at $53 billion.

More recently, Palm has shown signs of weakness. Nonetheless, it bested Microsoft for five years. Why did it succeed where so many others had failed? In large part, because of management’s intuitive use of judo-strategy principles and techniques.

What Is Judo Strategy?

Judo strategy is an approach to competition that emphasizes skill rather than size or strength. It has two sources: the Japanese martial art of judo, which teaches a competitor to use opponents’ own strength against them, and judo economics, an early effort to show how a small company can use a similar strategy to gain a foothold in a market dominated by a large incumbent.2

Building on those foundations, we argue that companies can win against larger or stronger competitors by mastering three core principles: movement, balance and leverage. In judo, those principles work closely together. As one expert wrote, “Through movement the opponent is led into an unbalanced position. Then he is thrown either by some form of leverage or by stopping or sweeping away some part of his body or limbs.”3 Analogously, each principle provides a different piece of the strategy puzzle in business competition. Through movement, managers can seize the lead and make the most of their initial advantage. By maintaining balance, they can successfully engage with opponents and respond to rivals’ attacks. And finally, by exploiting leverage, they can transform their competitors’ strengths into strategic liabilities.

Judo strategy is most effective when the three principles are used in combination. But at different stages of competition, a single principle may play a particularly important role. In the early days, for example, before the contours of the competitive landscape have been fully defined, movement typically takes center stage. Mastering movement is a critical first step for any company challenging dominant players in an industry. Consequently, we will focus on the principle of movement and on the techniques Palm’s original leaders adopted to put the principle of movement to work.

Movement in Judo Strategy

Judo strategy, like judo, begins with movement. In judo, movement serves both offensive and defensive goals. Competitors use their quickness and agility to move into a position of relative strength while evading attack. Judo masters also use movement to take an opponent “out of his game,” as one Olympic medalist explained, or prevent him from employing his strongest techniques.4 Then, once he’s gained an edge, a skilled judoka follows through quickly, moving seamlessly from attack to attack. In a sport in which advantage can shift in a second, faltering on the follow-through can be a fatal mistake.

The same tactics can help companies seize and keep the lead away from powerful opponents, as Palm’s success vis-à-vis Microsoft shows. In their six years at the company’s helm, Hawkins and CEO Donna Dubinsky displayed a firm intuitive grasp of three key movement-related techniques. They skillfully implemented the puppy-dog ploy, steadily building market momentum while cultivating an unthreatening image in order to avoid provoking the competition.5 They also moved quickly to define the competitive space, challenging Microsoft to compete using new and unfamiliar rules. And finally, they followed through fast, capitalizing on their initial advantage with a well-executed plan of continuous attack. As a result, by mid-1998, when Dubinsky and Hawkins left to start a new venture, Palm held close to 80% of the hand-held computing market, far outstripping products based on Microsoft’s hand-held system, Windows CE.

The Puppy-Dog Ploy

In any kind of competition, your first goal is to stay in the game. So when facing stronger rivals, avoid head-to-head battles that you’re too weak to win. Keep a low profile and try to look inoffensive — like a puppy dog — until you’re strong enough to fight.

That advice goes against the grain for many ambitious executives. In a crowded marketplace, it’s often said, you have to shout to be heard. You have to be aggressive to win customers and build value, and often that means attacking giants head-on. There’s a kernel of truth in that argument. In order to make a dent in the market, you do have to attract attention and win credibility among customers, partners and sometimes the media as well. That is particularly true in business-to-business markets and in sectors in which network effects are strong. But in most cases, the goal can be accomplished without initiating or inviting a full frontal attack.

The success of Palm Computing’s low-key approach to the market makes the lesson clear. Palm introduced its first hand-held organizer, the Pilot, with characteristic deftness in January 1996. Senior executives at U.S. Robotics (USR), which acquired Palm in 1995, had pushed for the debut to take place at the massive Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. But in keeping with the spirit of the puppy-dog ploy, the Palm team chose Demo, an exclusive industry conclave. Even as part of USR, Dubinsky believed, Palm lacked the resources to attack the mass market head-on. “We felt that the Pilot would get lost in Las Vegas. Our only chance of success would be if the early adopters liked it,” she explains.6

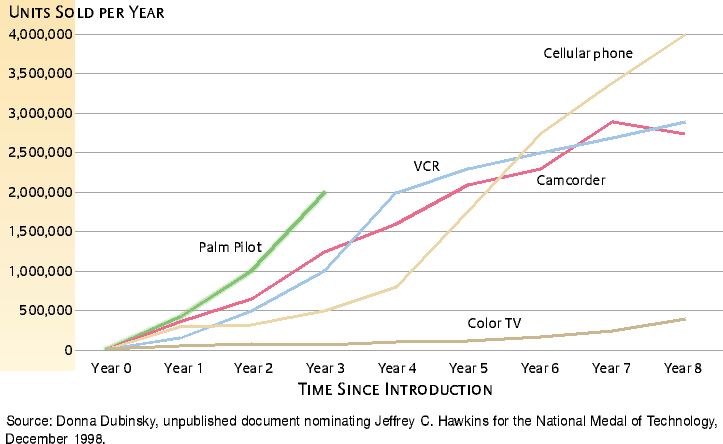

And like it they did. Although sales of the Pilot were flat at around 10,000 units per month for the first five months, those first 50,000 users turned out to be worth their weight in gold. Earning more than $100,000 a year on average, they were self-rated computer experts, nearly all between the ages of 35 and 45, and 95% male. “We called them the rich male nerds,” Dubinsky says affectionately. “Those 50,000 guys became our sales force. They went out and told all their colleagues and their neighbors and their friends. They bought it for their friends and their colleagues for Christmas, and that was how the Pilot started taking off.” (See “The Pilot Becomes One of the Fastest-Growing Consumer Devices in History.”)

At that point, many executives would have been tempted to make the most of their momentum by pumping up the hype. Netscape, for example, drew attention by posing as a giant-killer early in the game. Co-founder Jim Clark took the stage at an industry event in spring 1995 to label Microsoft the “Death Star” and to depict Netscape as the rebel alliance that would liberate the galaxy. Meanwhile, Marc Andreessen, then a brash 24-year-old, was busy telling interviewers that the rise of the Web would make Microsoft Windows obsolete: “… nothing more than a mundane collection of not entirely debugged device drivers,” as he was quoted to have said.7 Netscape’s aggressive positioning helped the startup in the battle for publicity, and for a while its fortunes soared. But winning the battle ultimately helped Netscape lose the war. By going out of their way to taunt Microsoft, Clark and Andreessen helped push the Internet to the top of Bill Gates’ list of priorities and secured Netscape’s position as Enemy No. 1.

Palm took the opposite approach. (See “Movement at Palm: The Puppy-Dog Ploy.”) Rather than play up the Pilot’s full potential, Dubinsky and Hawkins deliberately positioned themselves on the periphery of the personal computer world. “We didn’t call [the Pilot] a computer; we didn’t call it a PDA [personal digital assistant],” Dubinsky recalls. “We said, ‘This is just a little organizer that happens to connect to your PC.’ ” At one level, the message was aimed at consumers, whose expectations had been raised and dashed by other hand-held machines. “There was so much overpromising and under-delivering, we had to swing to the other extreme,” Dubinsky believes. But Palm’s competitors were an equally critical audience. By positioning the Pilot as a “companion to the PC, not a substitute,” as Hawkins said, Palm hoped to stay out of Microsoft’s sights.

Fortunately, when Palm began to take off, the hand-held market was a sideline for computing’s heavy hitters. In the glare of the Internet, Palm’s niche was easy to overlook, and nowhere was this more true than at Microsoft, which was focusing its fire on Netscape by 1996. “We were just joyous when we realized that the Internet was happening,” Dubinsky recalls. “We said, ‘Oh, that’s going to distract [Bill] Gates for a long time.’ We always felt that the hand-held guys at Microsoft were the B players. It never got strategic attention. It was never anywhere near as critical on Gates’ list. The Internet came to really dominate the new direction of the company and justifiably so.”

But Palm didn’t take Microsoft’s benign neglect for granted. Dubinsky and Hawkins remained cautious when it came to positioning the Pilot, staying away from the areas where Microsoft was most sensitive to attack. Netscape had struck for the jugular by positioning Navigator as an alternative software platform with the potential to supersede Windows, the foundation of Microsoft’s strength. Palm, by contrast, defined its product not as a platform, but as a piece of hardware — a device — even though company executives realized from the beginning that it was both. “We always said, ‘Look, if Microsoft had a decent platform we would consider it. We are first and foremost a device company,’ ” Dubinsky says. “Of course, they didn’t have a decent platform, so it was sort of a moot point.”

Palm’s moves were not bold or glamorous, but they worked. According to Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, Palm still hadn’t grabbed his attention as an important competitor two years after the Pilot’s debut. “They must have been on my radar screen by early ’98,” he mused in an interview, “but not at the top of my radar screen.” That was due in part to the distractions of the Internet. But it also reflected Palm’s success in portraying the hand-held market as an unthreatening niche, as Ballmer’s reasoning revealed. “Let’s say the market quadruples,” he observed. “Roughly we’re talking about $400 million in potential operating profits for all players. Palm’s still going to have some share, and then I have to split the rest with my OEMs [original equipment manufacturers]. At the end of the day, the total profit pool in this business doesn’t excite most of our OEMs or Microsoft.”

By contrast, if Palm had positioned the Pilot as a PC alternative and the Palm operating system as a direct threat to Windows, Ballmer clearly would have found a great deal more to get excited about. And Palm, of course, would have had a great deal more to fear.

Define the Competitive Space

By playing the puppy dog, Dubinsky and Hawkins bought some time. But they realized that their respite was likely to be brief. Nobody gets to be a category leader without developing a keen sense for hidden threats. Sooner or later, it was clear, Microsoft would move aggressively into hand-held computing. And once that happened, Palm would face a dangerous opponent hundreds of times its size. (See “Movement at Palm: Define the Competitive Space.”)

Given the mismatch in resources between the two companies, Palm’s best chance lay in preemptively defining the competitive space. By choosing the rules, parameters and boundaries of competition, Palm could gain a critical edge by taking Microsoft “out of its game.” Most champions rise to the top by learning to do a few key things better than anybody else. Trying to compete with powerful players at what they do best is a quick route to defeat. But all champions have areas of weakness, often precisely because of investing heavily in core strengths. Challengers can take advantage of those weak points to define a game that they can win.

Palm successfully implemented that technique by changing the criteria by which hand-held computing products were judged. Early on, everyone believed that success in the PDA and personal-organizer category required packing more and more features and applications into a tiny device. “I can’t tell you the number of meetings where people said, ‘You can’t do a product unless it’s got embedded wireless communications; no one is going to want it. You can’t do a product without a spreadsheet. You can’t do a product that doesn’t have a PC card slot,’ ” Dubinsky recalls.

But Palm chose a different path. “We looked at this list of things [that people in the industry] told us we had to have, and we said, ‘Most of the products available today have all those things, and they’re failing,’ ” Hawkins recounts. So the Pilot, in many ways, was designed as the un-PDA. Palm’s first device did not do all that much. But it did a few important things —notably, organizing a calendar and address book — simply, quickly and very well. The Pilot was, in Dubinsky’s words, “extremely high-performance from a user perspective.” There was no boot-up delay and no hourglass or wait cursor of any sort. Moreover, the Pilot adhered to the telecommunications-industry standard of “five nines,” working 99.999% of the time, whereas PC programs often crashed several times a day.

In redefining the category’s goals, Palm did more than build a better product. Hawkins and Dubinsky laid the groundwork for a style of competition that strongly favored Palm. If Palm had set out to create the digital equivalent of a Swiss army knife, crammed with specialized tools, its chances of winning would have been slim. Competing on the basis of features lists was a large company’s game. But simplicity, usability and elegance were standards that challenged Microsoft’s competencies. That gave Palm a fighting chance.

Rob Haitani, one of Palm’s senior product designers, captured the company’s strategy in a tongue-in-cheek presentation titled “The Zen of Palm.” The presentation posed a series of riddles, starting with “How can a gorilla learn to fly?” The reply: “Only by abandoning the essence of the gorilla.” Microsoft was the gorilla. By embracing simplicity, Palm would force the software giant to abandon its favorite tactic (adding more features) in order to compete. Odds were that Microsoft would be unable to perform such an unnatural act. “Microsoft won’t crush us,” “The Zen of Palm” maintained, as long as Palm remained faithful to its own approach.

That was particularly true, Palm executives believed, because Microsoft’s traditional business model was ill-suited to the new competitive space Palm had defined. The software giant typically licensed its software to a wide variety of partners, which embedded it in different hardware designs. Or as Dubinsky puts it, Microsoft would “do this sort of reference design and throw it over the fence to their partners” — hardware manufacturers such as Compaq, Dell and IBM.

By contrast, Palm tightly integrated software and hardware design under the same roof. A single vision shaped the Pilot, ensuring that its hardware (the buttons, stylus and screen) and its software (the operating system and applications) formed a cohesive whole. In a game in which elegance had become one of the yardsticks of success, the approach significantly improved Palm’s chances of scoring a win.

Follow Through Fast

By defining the competitive space and using the puppy-dog ploy, Palm built a healthy lead. By the end of 1996, the company had raced to first place in the fragmented hand-held-computing category, with 51% of the market. By then, however, Microsoft was on the move. After two failed efforts in five years, Microsoft returned to the hand-held market in November 1996 with its third pocket-sized operating system, Windows CE.

Early CE devices were no match for Palm’s when it came to usability, size and speed. But given Microsoft’s track record, Dubinsky and Hawkins knew that the devices would eventually improve. And once Microsoft had a comparable product, it would be able to bring its traditional strengths to bear: the marketing muscle of a multibillion-dollar company and the coalition of big-name manufacturers (including Compaq, Hewlett-Packard and NEC) on its side. In order to avoid being crushed by that juggernaut, Palm had to maintain and, if possible, increase its lead over its rival. That involved two tasks: constantly moving the product forward and simultaneously building a massive installed base.

In order to stay ahead of Microsoft, Palm turned itself into a moving target, bringing new product generations to market at least once a year. (See “Movement at Palm: Follow Through Fast.”) The PalmPilot, a more rugged version of the original model, with backlighting and new applications, followed the Pilot by 11 months. Palm engineers then started working on the Palm III, V and VII, which ran on parallel tracks. (See “Speeding to Market.”) The management challenges were great, but the decision to run three projects concurrently grew out of the conviction that such a strategy would allow Palm to leapfrog the competition.

Whereas the Palm III was an evolutionary follow-on product, the Palm V and VII reflected much more ambitious efforts to rethink the product and continuously redefine the competitive space. “The Palm V was all about style, and style was not one of Microsoft’s fortes,” Hawkins observes. “And with the Palm VII, we created a truly integrated, wireless-connectivity solution, which was again rewriting the rules. No one had done anything like that. I said to myself, ‘Microsoft can’t do this.’ And it’s true. They can’t.”

Three key practices helped Palm move to market at a world-class pace. The first was the design philosophy that drove the entire process. Palm’s engineers avoided rocket science and lengthy wish lists that could delay a launch by months or even years. “We didn’t try to do cutting edge,” observes Mike Gallucci, Palm’s head of manufacturing logistics. “What we did was simplicity in its most elegant form.” As a result, the company avoided the technology-related delays that slow down many ambitious startups.

Palm’s feet-on-the-ground approach also was reflected in its reliance on concurrent engineering. Traditional product development unfolds sequentially. As Gallucci explains, “Engineering goes off and designs the product and then hands it over to manufacturing, and then manufacturing tries to go figure out how to manufacture it and finds a lot of problems.” By contrast, Palm focused on implementation upfront. “From the minute Jeff woke up in the middle of the night in his pajamas and said, ‘Eureka! I’ve got the next brilliant idea for a product!’ we formed cross-functional teams that included manufacturing. And we were in there from day one giving input and being part of that design team to make sure that the product was manufacturable,” he recalls.

Finally, Palm turned to outside partners to handle many noncore tasks rather than spend scarce time and resources developing noncore capabilities in-house. “We didn’t have many people — maybe 25, maybe 28,” Dubinsky says of the early days. So the company outsourced a lot, including electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, industrial design and manufacturing. Although Hawkins’ vision guided the development of all the Pilot’s components, Palm engineers developed only the software (the operating system and the main applications — a calendar, address book, to-do list and memo pad) on their own.

As Palm’s engineering teams streamlined the development process for speed, the company’s marketers focused on reaching critical mass by starting with low prices ($300 as opposed to $500 for a typical Windows CE device) and lowering them every year. Palm executives often found themselves defending that strategy to higher-level managers at USR and 3Com, which acquired USR in 1997. As marketing head Ed Colligan recalls, “Eric Benhamou [3Com CEO] kept saying, ‘Why are you lowering prices? You own this market.’ And we just kept saying, ‘Because we can and we should and we want to be aggressive and we’ve got to keep going to market. We’re going to keep pushing this so that there’s no room for people to enter.’ ”

Getting early market share was critical because, despite the company’s early positioning as a device, Palm was creating a platform. And as Dubinsky noted, “The idea in the beginning of a platform business is to get as much market share and installed base as possible and to draw as many developers as possible. And then the network effects kick in. Over time, we can have a product line that supports higher-margin products, and we’ll be protected against the competition.”

The idea was that by building market share, Palm would encourage developers to create applications that increased the value of its products. The proliferation of applications would then drive further adoption, which would attract even more developers, until Palm had locked in a virtually unassailable installed base — and turned a handy little organizer into a field of dreams. Palm could help that process along by reaching out to developers. But it couldn’t launch an all-out charm offensive without jeopardizing the puppy-dog ploy. So instead, the company quietly released a software-development kit, together with the Pilot, in early 1996. In addition, to make it easier for developers to create new software for the Pilot, Hawkins took the unusual step of publishing the source code for Palm’s basic applications two years before the open-source movement really took off. But the biggest inducement the company could offer other programmers was a proven market for their wares. It was only after Palm had reached one million users that the company began to court developers aggressively, holding its first developers conference in October 1997.

That strategy gave Palm a critical weapon in the battle with Microsoft to win developers’ hearts and minds. Microsoft could offer other software companies resources that Palm could never match. “They’d offer funding for the initial development,” Colligan explains. “They held all the development kitchens. They always put on a big dog-and-pony show, and we did our little nothing thing.” What’s more, Microsoft’s fearsome reputation carried a lot of weight. Colligan recalls that when Windows CE was released “people did have to say, ‘Hmm, is Microsoft just going to kill Palm?’ And for a small point in time, a lot of people started going to the Microsoft product.” But Palm was able to win back many of the defectors with a simple argument: Palm had more buyers in its camp. By the end of 1997, Palm held two-thirds of the market, whereas products based on Windows CE trailed far behind.

Throughout this period, Palm had a wealth of opportunities to extend its brand. “We had people knocking at our door to license this bit or that bit for this thing or the other thing, whether it was for set-top boxes or desktop big-screen phones,” Dubinsky recalls. “We were constantly struggling with the tension between trying to take advantage of this opportunity we had created, which seemed limitless and very broad, and trying to retain a small, focused organization that could deliver.”

In a few cases, Palm decided to go for the opportunity. In September 1997, Dubinsky negotiated a partnership with IBM to sell the Pilot, relabeled the IBM WorkPad. IBM also agreed to handle marketing and sales for the Pilot in Japan. One month later, Palm and Symbol Technologies announced an alliance to deliver Palm-based products for vertical markets in areas such as retail, parcel delivery and manufacturing. And in February 1998, Qualcomm signed up to incorporate the Palm operating system into cellular phones.

In most cases, however, Palm turned its suitors down. Even as sales skyrocketed, Dubinsky and Hawkins needed to focus their resources on a single goal: building and selling the best hand-held device in the world. If the company overextended itself, it might falter and create an opening for the competition. As a result, Dubinsky explains, “We declined most of our licensing opportunities because we felt that the fit was not great and therefore the amount of work to force our product into what they had in mind would be a big diversion, a lot of effort for what was not our core business. … It’s very hard to say no, but those, I think, were decisions that we were very good at making.”

Beyond Movement

As the story of Palm Computing shows, movement can be a powerful tool for companies facing formidable competition. By mastering movement, Donna Dubinsky and Jeff Hawkins built Palm into the leading player in hand-held computing and quickly forged ahead of the largest software company in the world. By quietly courting early adopters and positioning alongside competitors — while maintaining its product focus and designing internal processes for speed — Palm built extraordinary share of mind and market without provoking a fatal attack.

Our account would be incomplete, however, without an important caveat: As Palm found, movement techniques often come with an expiration date built in. Defining the competitive space creates a window of opportunity, but eventually most competitors will learn to play the new game. Similarly, even the most skillful judo strategists will find it a challenge to maintain the puppy-dog ploy over time. As companies become more successful, they almost inevitably attract their competitors’ attention.

For Palm, that turning point came in January 1998, when Microsoft stepped up its attack on the hand-held market by introducing a new version of its operating system, Windows CE 2.0, and a new device, the Palm PC. At the end of their Palm PC briefing for developers, Microsoft executives showed a slide that superimposed Palm’s logo on a target. It was clear that Palm’s days as a puppy dog had run their course. In the future, no amount of clever positioning would avert a full-scale assault.

Consequently, Palm had to go back to the judo strategy toolbox in order to compete effectively over the longer run. For example, Dubinsky and Hawkins turned to balance and a technique we call “avoid tit for tat” to respond to the introduction of the Palm PC. The Palm PC posed a much greater threat than earlier products based on Windows CE. Unlike its predecessors, which weighed in at close to two pounds, it was virtually indistinguishable from Palm’s hand-helds in size and design, and it was priced at roughly the level of the Palm III, which debuted around the same time. In addition, the Palm PC boasted a host of new features, including a voice memo recorder, an LED light that flashed on to remind the user of appointments, and a larger screen.

Palm faced considerable pressure to match Microsoft’s latest moves. “The press was coming out and saying, ‘CE products have more features than Palm; they’re going to squash Palm,’ and people believed it, even inside the company,” Hawkins recalls. But Hawkins and Dubinsky were convinced that getting dragged into a tit-for-tat battle could be a fatal mistake. (See “Balance at Palm: Avoid Tit for Tat.”) Palm had succeeded by defining the rules and setting the pace for the industry. If the company succumbed to the temptation to copy Microsoft, it would be thrown on the defensive and lose its edge. As “The Zen of Palm” warned, “Frankly, my bigger worry is that we try to play their game. It’s tempting for eagles to look at gorillas and think, ‘Hey, those guys have arms. We should get arms. And opposable thumbs! Think of what we could do with those.’ Next thing you know, your eagles become fat, slow and ugly.”

Rather than run that risk, Hawkins and Dubinsky made a conscious decision to avoid a battle on features. Many within the organization found the approach hard to swallow, but Hawkins and Dubinsky stuck to their position, refusing, for example, to copy the voice recorder in Windows CE. In the first place, Dubinsky says, the product was terrible. “Your voice sounded like you were talking into a [helium] balloon,” she laughs. Market research also showed that most consumers had little interest in such a feature. But perhaps more important, restraint was the core of Palm’s approach to competition. “We never allowed ourselves to get on the defensive,” Mike Gallucci recalls. “Our attitude was: We have the lead; we know what we’re doing. Don’t feel like you have to react.”

Beyond Palm Computing

By mastering movement and adding balance to their repertoire at a critical stage, Donna Dubinsky and Jeff Hawkins guided Palm to a commanding position in hand-held computing. In early 2001, nearly five years after the Pilot’s debut, devices based on the Palm operating system accounted for 87% of the retail market, whereas Pocket PCs, the third generation of Windows CE hand-helds, had about 10%.8 But by then, Dubinsky and Hawkins were no longer around to share in Palm’s triumphs. Instead, they were heading up a new venture, Handspring, which had quickly emerged as the greatest short-term threat to Palm.

Hawkins and Dubinsky founded Handspring in the fall of 1998, after failing to convince 3Com executives to spin out the Palm division.9 The company’s first product was the Visor, a hand-held device based on the Palm operating system, which debuted in September 1999. The Visor was fully compatible with the existing base of Palm applications, but it also featured an important innovation: an expansion slot that allowed the Visor to become anything from a digital camera to an MP3 player to a cellular phone.10 In its first week in retail distribution, the aggressively priced Visor became the channel’s best-selling hand-held device. Less than a year later, Handspring accounted for more than 40% of Palm-based retail sales — becoming the only company to date to take meaningful share away from Palm.

Handspring’s achievement is not just testimony to its founders’ strategic ability. It also illustrates one of the ironies of judo strategy. With success comes vulnerability: the better your performance, the greater your danger of coming under attack. By investing over time in specific skills and strengths, you create opportunities that perceptive rivals can exploit. In other words, you risk becoming the target of another and possibly better judo strategist.

It is too early to say whether Palm will overcome the challenges that its success has helped create. In addition to Handspring, the new Palm team faces renewed competition from Microsoft, which remains determined to win the battle for hand-held computing. “We can’t afford not to. We can’t afford to give up a potential choke point on our core platform,” as Steve Ballmer explains.

Palm may find itself at a disadvantage as the focus of competition shifts from consumers to the corporate market, where Microsoft is solidly entrenched. And the company’s recent stumbles have not helped its cause. The pace of innovation at Palm has clearly slowed, while execution problems have begun to emerge. In early 2001, for example, the mistimed introduction of Palm’s newest models — the m500 and m505 — significantly dampened demand for older products. Combined with a large inventory buildup, this development forced the company to slash prices, cutting heavily into the bottom line. Nonetheless, for all its troubles, Palm remains the company to beat — thanks in large part to its early reliance on judo strategy.

By mastering the principles of judo strategy, like Palm, and learning to implement them through specific techniques, any company can compete more effectively with stronger opponents. Managers in a wide range of industries can benefit from Palm’s example by adopting the judo metaphor as a guide to action. Old Economy and New Economy players alike, businesses both large and small, can reap considerable rewards from the approach — as we found after studying companies as varied as Juniper Networks, Intuit, Frontier Airlines and Charles Schwab Corp.

Judo strategy is not a rigid formula to be followed step by step. Depending on the nature of their competition, companies will combine and implement the principles in different ways. Yet, however they approach judo strategy, the first steps toward beating a bigger, stronger player are using the puppy-dog ploy to stay out of their competitors’ sights, defining the competitive space to establish their game, and following through fast to build a big lead before competitors learn how to respond.

References

1. The article is adapted from the authors’ book, “Judo Strategy: Turning Your Competitors’ Strength to Your Advantage” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001).

2. Judith R. Gelman and Steven C. Salop, “Judo Economics: Capacity Limitations and Coupon Competition,” Rand Journal of Economics 14 (fall 1983): 315–325.

3. Charles Yerkow, “Modern Judo: The Complete Ju-Jutsu Library” (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Military Service Publishing Co., 1942), 44.

4.Jimmy Pedro, telephone interview, June 28, 1999.

5. We have borrowed this term from Drew Fudenberg and Jean Tirole, “The Fat-Cat Effect, the Puppy-Dog Ploy and the Lean and Hungry Look,” American Economic Review 74 (May 1984): 361–366.

6. All quotations from Palm and Microsoft executives are taken from interviews the authors conducted in July 1999, January 2000, July 2000 and August 2000.

7. Bob Metcalfe, “Without Case of Vapors, Netscape’s Tools Will Give Blackbird Reason To Squawk,” InfoWorld, Sept. 18, 1995, 111.

8. Ian Fried, “Palm, Handspring Lose Ground to Microsoft,” CNET News.com, Feb. 20, 2001, http://news.cnet.com/news/0-1006-200-4880476.html.

9. 3Com later reversed that decision, spinning Palm off in March 2000; three months later Handspring went public.

10. Handspring’s product strategy was based on a technique we term “push when pulled.” See Yoffie, “Judo Strategy,” 59–64, 115–116.