Responding to Crises With Speed and Agility

When faced with a crisis, companies should dial up two interdependent drivers — speed and agility — to seize opportunities.

Topics

Etsy is a U.S.-based e-commerce company best known for connecting individual crafters and artisans directly with consumers. But when CEO Josh Silverman heard in early April that face masks would be a key component of the general public’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic, he mobilized sellers — fast. Within days of the release of public health guidelines, Etsy had more than 20,000 sellers with masks ready for purchase. As Silverman put it, “It’s as if we woke up and it was suddenly Cyber Monday, but everyone in the world wanted only one product, and it was a product that basically didn’t exist two weeks before.”

This example highlights two interdependent drivers that have permeated the global business environment during the pandemic: speed and agility. Etsy’s booming sales also highlight what’s possible when businesses exploit both qualities simultaneously. While many retailers are struggling, Etsy’s revenue for the second quarter of 2020 is expected to increase by 80%. Academic research and experience show that Etsy’s experience is not unique; organizational speed and agility strongly influence company performance.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

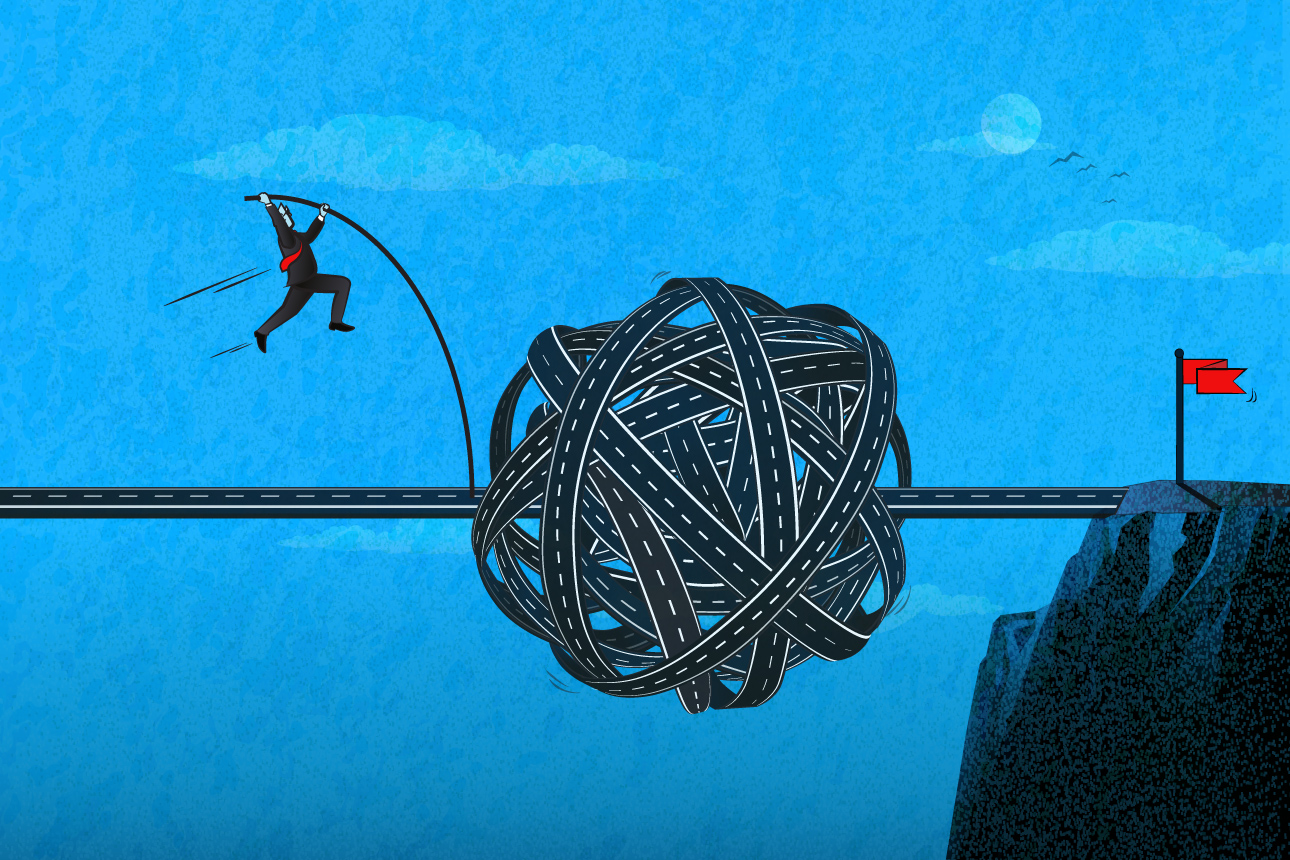

It seems obvious that when faced with a crisis, companies should simply dial up more speed and agility to seize an opportunity. But not all companies do. Speed is not simply an attribute of an organizational activity tied to clock time. Rather, speed is a complex, performance-enhancing organizational capability that requires a holistic approach to its development and execution. Speed alone enables companies to operate quickly only in already established product domains. During a crisis, companies must also demonstrate agility, a capability that allows the organization to pivot to adjacent or entirely new product domains.

Organizational Speed Is a Capability

Organizational speed depends on three interconnected capabilities: recognition speed (how quickly external stimuli are recognized as an opportunity/threat), decision speed (how quickly decisions for action are made), and execution speed (how quickly resources, people, and/or processes are mobilized to support the action).

Consider Peloton, which sells computer-linked fitness equipment and subscriptions to digital workout classes. As gyms closed under COVID-19, demand for in-home exercise equipment increased sharply. Peloton’s tech-enabled products and online streaming platform made it ideally suited to handle the increased demand for in-home workouts. But the company couldn’t increase production of its exercise bikes quickly enough to meet surging demand. Many dissatisfied customers canceled their orders when they learned of delivery delays of six to 10 weeks.

What went wrong? A series of questions and answers could help diagnose where Peloton lacked the speed to meet an unexpected opportunity.

- Recognition speed: Did Peloton recognize COVID-19 as an opportunity quickly enough? No. CEO John Foley acknowledged that he underestimated the seriousness, speed, and potential of the coronavirus’s threat.

- Decision speed: Were decisions related to production increases slowed, and how — by analysis paralysis, politics, or deeply rooted biases? The answer is that Peloton may have choked due to excessive internal demands. Peloton entered the fourth quarter of 2019 facing both existing production back orders and the launch of its initial public offering. It was not until November 2019 that the company purchased two manufacturing businesses in Asia to expand its production capacity. It appears that Peloton simply may not have had enough time to integrate its expanded production capabilities to meet demand by the time the coronavirus crisis emerged.

- Execution speed: Were supply chain bottlenecks the main reason for distribution constraints? Yes. Peloton was slow to respond to the health concerns of its employees, so distribution and installation services suffered. In fact, Peloton mistakenly assumed that extra pay would keep delivery and installation employees on the job during the pandemic despite increased health risks to workers. Distribution and production problems notwithstanding, COVID-19 brought Peloton’s “high touch” delivery and installation capacity to a screeching halt.

These questions illustrate how critical it is for all aspects of speed to be in sync. When they are, companies are able to speed up multiple organizational activities simultaneously. This is called entrainment, a phenomenon in which two or more independent processes synchronize with each other.1 Entrainment was evident when Johnson Controls worked on the Army Corps of Engineers’ 1,000-bed hospital for COVID-19 patients on Long Island, New York. Johnson Controls was tapped to equip the hospital with a video surveillance system, a nurse call system, fire alarms, and wireless networks. A project that would normally take six months to complete took Johnson Controls just 20 days. Although many different parts of Johnson Controls’ operations were involved in the hospital project — design, production, logistics, and so on — each was accelerated and synchronized, enabling the company to complete the project at record speed.

In the absence of entrainment, when companies are speedy in some activities but slow in others, slippage occurs. The response of many airlines to COVID-19 exhibited slippage. Most airlines were quick to recognize COVID-19 as a severe threat and quickly changed many of their travel policies, such as limiting the number of passengers on flights, conducting preflight temperature checks, and requiring passengers to wear masks. However, most airlines have been inconsistent in implementing those policy changes and slow to issue refunds on canceled flights. Some airlines required refund requests to be processed only over the phone, causing serious delays. Some airlines also recognized that it would be difficult to enforce some safety measures, such as requiring masks, in all cases, which contributed to the industry’s inability to implement such measures quickly and consistently. Here, the call center bottleneck plus irregular policy enforcement disrupted the harmonic relationship between recognition, decision, and execution speed.

Agility During a Crisis

Both Johnson Controls and Peloton sought to respond to COVID-19 within their established product domains. However, some companies responded in profoundly unique and surprising ways, with agile pivots to new product domains entirely. Organizational agility is a bundle of dynamic capabilities: the alertness to the need for change, the ability to decide on a new course of action, and the ability to effectively reconfigure and mobilize the resources necessary for change. When faced with an external stimulus (like COVID-19), an organization must enact all three elements of agility to effectively carry out change.

Two companies exemplify the effective use of agility to respond to a crisis. Isinnova is an Italian startup that uses 3D printing technology to manufacture full-face recreational snorkeling masks. Noting the acute shortage of respiratory ventilators and leveraging the flexibility inherent in its 3D printing capabilities, Isinnova redirected its manufacturing processes and resources to produce ventilator masks instead of snorkeling masks.

Similarly, General Motors began manufacturing respiratory ventilators after it was mandated to do so under the federal Defense Production Act. GM pursued a new course of action by contracting with a third-party coproducer, Ventec Life Systems. It then redirected its extensive supply chain to have parts common to both its autos and ventilators shipped to its Kokomo, Indiana, plant for assembly. GM already had technological capabilities in sophisticated automobile electronics. Switching to ventilators was merely a matter of adjusting its supply chain.

Linking Organizational Speed and Agility

Connecting speed and agility has multiple implications for managers. First, the Etsy and GM examples highlight that in crisis situations, the joint influence of speed and agility is critical for achieving strong company performance. Both speed and agility helped Etsy gain 4 million new customers in April, 32% of whom made a subsequent purchase after buying a mask.

Speed and agility are interdependent. When confronted with a profoundly disruptive stimulus, managers need to be alert to change and quickly recognize the opportunity/threat potential of the stimulus. Effective crisis response also requires the ability to quickly make decisions, perhaps using novel information, and to reconfigure and synchronize organizational tasks to meet the challenge.

Our analysis also reveals that speed and agility are particularly critical for companies in essential industries such as medical supplies, e-commerce, transportation and logistics, health care, and agriculture. COVID-19 forced businesses in these areas to adjust quickly as demand for their vitally needed goods and services rose rapidly. Because Peloton’s products are related to personal health, sales of its tech-laden stationary bikes spiked by 66% during the pandemic.

Finally, managers need to recognize that speed and agility are related to other aspects of the organization, such as organizational structure, company resources, employee compensation, and executive leadership. For example, under the leadership of Mary Barra, GM’s CEO, the company had already begun to cut costs, streamline operations, and sell money-losing operations before COVID-19. A leaner and more efficient GM structure thereby enabled the company to quickly pivot to ventilator production. To respond to COVID-19, Johnson Controls appointed an executive task force to develop and execute plans quickly. To make the appropriate changes, the task force watched for bottlenecks, expedited contracts, and pushed for employee innovation on the fly.

Conclusion

Recent news reports and case studies reveal the acute need for managers to step back, discover, and leverage new ways to think about and implement speed and agility in organizational routines and operations. This involves a sustained commitment to developing higher levels of organizational readiness, flexibility, and resilience supported by the people, processes, and principles that guide and support the organization. Ultimately, to successfully adapt to and achieve strong performance in times of crisis, managers need to effectively integrate speed and agility in all of their operations.

References

1. L. Pérez-Nordtvedt, G. Tyge Payne, J.C. Short, et al., “An Entrainment-Based Model of Temporal Organizational Fit, Misfit, and Performance,” Organization Science 19, no. 5 (October 2008): 785-801.