Should Multinationals Invest in Africa?

For most multinational corporations (MNCs), Africa is the forgotten continent. Characterized by the media mostly in terms of political turmoil, malnutrition, and AIDS, Africa seems inconsequential as a potential market or as a low-cost manufacturing source. Yet several MNCs enjoy good, sustained profitability from their African operations. In addition, substantial political and economic changes now underway in many African countries prompt a closer look at the business opportunities in this emerging continent of forty-nine very diverse nations.

Our purpose here is to highlight these changes and to provide practical advice on business strategy, marketing, and organization to companies doing or considering doing business in Africa. We focus on sub-Saharan Africa and therefore exclude the Arab countries of North Africa that are more often identified with the Middle East. We studied a variety of firms, representing leading consumer, industrial, and service companies that are marketing and, in some cases, manufacturing in Africa.

Small but Growing Involvement

The commercial importance of Africa to multinationals is limited but increasing:

- Exports to Africa from the United States are small but expanding rapidly. In 1991, exports rose 18 percent to $4.8 billion with 60 percent going to Nigeria and South Africa, which account for 28 percent of the continent’s population. This growth rate was two and a half times that of total U.S. exports. Between 1988 and 1991, exports to the region rose 70 percent.1

- Of the United States’ $11.7 billion imports from Africa, almost all were oil and other commodities. Africa accounts for only 2 percent of U.S. trade, but, put in perspective, it still exceeds that with the former communist countries of Eastern and Central Europe. Europe’s trade with Africa is almost double that of the United States, given the traditional ties with its former colonies.

- Most North American and European multinationals generate less than 1 percent of their revenues and income from African operations. However, there are important exceptions, such as the Coca-Cola Company, whose African operations account for 5 percent of revenues.

- In 1992, multinationals invested $2.1 billion in Africa. While this amounted to only 5.8 percent of the total direct foreign investment in developing countries, the growth rate of foreign investment during the 1981–1992 period in Africa exceeded that in all other regions.2

- Demographically, the African continent represents the fastest expanding marketplace. Its 600 million people are growing at an average annual rate of 3 percent, compared to 0.5 percent in developed countries.3 Its resultant age structure means that about 40 percent of the population is under eighteen years of age. Thus, for demographically-driven or youth-oriented products, these are the most active growth markets. For Pioneer Hi-Bred International, the world leader in hybrid corn, Africa was its largest market outside of the Americas and Europe, producing profits of $6 million on sales of $28 million.

The Economic Constraint

Despite these positive aspects, Africa’s poverty continues to constrain its economic attractiveness. Average annual per capita income in 1990 was only $340, about the same as South Asia but far behind East Asia’s and the Pacific countries’ $600 and Latin America’s and the Caribbean countries’ $2,180. The 1980s were a lost decade for most African (and Latin American) countries; while much of the developed world and the Far East enjoyed an economic boom, real per capita income in Africa fell 40 percent. The rate of population growth continues to outpace gross domestic product (GDP). Kenya’s population will double in the next eighteen years, but Kenyan food production in 1991 was 38 percent less per capita than it was forty years earlier.

Some additional statistics vividly demonstrate the poverty of the continent and how it has fallen further behind. The combined GDP of all the countries of sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) is less than the GDP of Belgium. In 1965, when Ghana became independent, its GDP per capita was similar to South Korea’s; today, it is less than 15 percent of South Korea’s. The sub-Saharan nations greatly increased their foreign debt during the 1980s, so that it is now larger than their GNP. They need about one-fifth of their export earnings to service this debt; this is a significant drain, but less than the 25 percent that Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East need to service their debts.4 Sub-Saharan Africa is heavily dependent on foreign aid, which accounts for 10 percent of its GNP and absorbs 35 percent of all the aid to developing countries. The region’s share of world trade is less than half what it was a decade ago, partly due to declining world prices of commodities, which constitute 91 percent of their exports.

The African countries that have achieved sustained economic growth are largely those blessed with commodities whose world market prices have remained strong. Oil-rich Gabon, for example, has a higher per capita income than South Africa. Botswana’s diamond-based economy grew the fastest in the world during the period from 1980 to 1987. Few African countries have significantly developed their manufacturing sectors; for example, in the ten member states of the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), only 12 percent of GDP is in manufacturing.5 The food processing and textile industries dominate the manufacturing sector throughout sub-Saharan Africa. In many African countries, agricultural output has improved, but a sustained tendency for rural dwellers to flock to the cities has resulted in high joblessness and marginal living conditions. A vigorous informal economy of microenterprises generally exists as these populations struggle for their economic survival.

Historical patterns of foreign direct investment (FDI) have not helped these trends. Half the FDI in African countries — compared to only 20 percent in non-African developing countries — continues to focus on mining and agriculture, reinforcing the commodity base of African economies. Only a quarter of the FDI targets the manufacturing sector, with more emphasis until recently on inefficient import substitution than on production for export. Of the remaining FDI in services, construction accounts for far more than financial services, which are sorely underdeveloped in many African countries.6 This pattern of FDI has limited the ability of African countries to capitalize on the generalized system of preferences (GSP) that reduces tariffs mainly on industrial rather than commodity exports from developing to developed countries. In 1990, only half of all developing country exports were covered, and the forty least developed countries in the world received 1 percent of the preferential tariff benefits, while Mexico alone accounted for 25 percent.7 Only 9 percent of the sub-Saharan nations’ exports are manufactures. The developed world seems determined to retain protectionist tariffs and subsidies that limit imports of agricultural commodities and low-cost textiles, although the European Common Market does give preferential access to exports from its former colonies.8

A weak manufacturing base, combined with national rivalries, national currencies, and poor distribution networks, results in a low level of intra-African trade. While some countries serve as important entrepôts (such as Botswana between South Africa and the rest of black Africa), they are exceptions. In 1990, only 5 percent of the foreign trade of the ten SADCC countries was with each other, as was only 4 percent of the foreign trade of the sixteen members of the Economic Community of West African States.

Yet, as indicated by the statistics presented in Tables 1 and 2 comparing ten of the principal countries in sub-Saharan Africa, there are substantial differences in their economic profiles and their potential for growth and industrial development. Recognizing and probing these differences is essential to identifying opportunities in this rapidly changing continent.

Signs of Hope

Africa is undergoing significant political and economic transformation. Following the initiation in 1986 of the United Nations recovery program for Africa, many African countries have seriously adopted political and economic reforms. In 1988, only a few nations had truly pluralistic democratic systems. By the end of 1992, fifteen more countries held multiparty elections. For example, in Zambia’s first open election in seventeen years, Frederick Chiluba’s movement for multiparty democracy defeated the incumbent, Kenneth Kaunda, who had been the nation’s leader since independence. A peaceful transition of power occurred.

Of course, this move to democracy does not necessarily guarantee greater stability, especially since political parties tend to represent particular ethnic groups, thereby fueling long-standing social animosities. The turbulence and often violent clashes occurring during the political campaigns in Kenya, Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Angola reveal this instability. Increasingly, donor nations and agencies are linking foreign aid to sustained economic reform and movement toward democratization. This does not necessarily mean an immediate switch to a multiparty system but it has reduced corruption, improved human rights, encouraged more financial accountability, and fostered freer judiciaries and media.9 All of these factors will create a healthier environment for foreign investment.

Thirty African countries are pursuing serious economic reform programs, twenty-three of them under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (see Table 3).10 These programs typically involve government spending cuts, increased taxes, reduced government subsidies to industry and agriculture, and higher interest rates to curb inflation. The African nations have achieved much lower annual inflation rates (29 percent) than Latin America (179 percent) or Eastern Europe (796 percent). Countries with IMF-approved structural adjustment programs, such as Ghana and Nigeria, registered real growth of 4.2 percent in the past three years compared to 2.6 percent in the three years preceding the adoption of these programs. Governments are privatizing many of the government-owned enterprises, thereby creating interesting acquisition opportunities for foreign investors. The governments are liberalizing their economies and these freer markets remove many of the costly and constraining regulations that restricted business development and fostered corruption.

The collapse of communism in Europe has accelerated the pace of reform. African countries are no longer able to play off East against West. Aid from Moscow has all but dried up. As a result, Western governments and agencies are imposing tighter conditions on their economic aid and are significantly decreasing the military component of the aid they give. In a time of economic recession in the industrialized nations, there is little political sympathy for foreign aid, particularly to Africa, which many see as a bottomless pit. As an example, the U.S. House of Representatives recently rejected a $25 billion foreign aid authorization bill. African governments are competing against each other and against the former communist countries of the East bloc for a limited supply of aid and will have to show sustained commitment to reforms if they want their aid to continue.11

South Africa’s progress, albeit slow, toward democracy and the end of apartheid is enhancing its role as an agent of investment and technology transfer in the region. Recent indications of cooperation between South Africa and its neighbors include the establishment of South African trade missions in six of ten SADCC countries; South African officials’ visits to Nigeria and other African countries; coventures involving Eksom, South Africa’s electric utility, and the governments of Zambia and Zimbabwe in developing a regional power grid for southern Africa; and the South African Development Bank’s involvement in rebuilding the port of Maputo in Mozambique.12 The lifting of trade sanctions on South Africa in July 1991 and the renewed availability of U.S. Eximbank credits in February 1992 should help to stimulate economic development throughout southern Africa. Many African business-people throughout the sub-Sahara see South Africa, whose $90 billion GDP is 36 percent of sub-Sahara’s combined GDP, as the future engine to revitalize the continent’s economy through new flows of investment, technology, and trade.13

MNC Investment and Entry Strategies

As part of the drive toward economic reform in many African countries, governments are relaxing majority local ownership and permit requirements for foreign investment, differential treatment of foreign and local companies, and restrictions on both the currency in which company capital can be held and on the repatriation of earnings. For example, Morocco has recently enjoyed strong growth in foreign investment following passage of a law permitting majority foreign ownership.

Many of the MNCs that have shown sustained interest in doing business in Africa have been mining and agricultural companies attracted by the continent’s rich natural resources. Africa has 86 percent of the world’s platinum reserves; the figures for cobalt, manganese and copper are 74 percent, 50 percent, and 30 percent, respectively. Chevron and other petroleum MNCs have also had long-standing interests in oil exploration and production in Angola and West Africa. Historically, these companies have focused on extracting the raw commodity and exporting it, but recently, some are investing in downstream processing to add value at the production site.

Most MNCs do business in Africa simply by exporting goods made elsewhere and selling through local agents or distributors. Demand is particularly strong for equipment in the mining, construction, food processing, textile, medical, materials handling, telecommunications, and computer industries. Governments or third-party agencies sponsoring development projects, such as the African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, and the World Bank, typically request tenders. The larger countries with higher per capita incomes represent the best targets for consumer product marketers.

Larger MNCs with a long-standing record of doing business in Africa and making relatively simple products are more likely to set up subsidiaries with manufacturing plants in the larger country markets and may also license production to third parties in some smaller countries. Johnson & Johnson, for example, makes consumer products in eight plants in Africa and has manufacturing licensees in two others. Many European multinationals have operated in Africa since colonial times. For example, since 1953, Unilever has produced basic consumer goods in Kenya. Some MNCs ship obsolete, lower-speed production lines from their Western plants to Africa when they set up local manufacturing. MNCs in extractive industries, including mining and agriculture, often coventure to spread risk and try to use local capital to finance their operations. The British company Booker McConnell has expanded its sugar and poultry output in Kenya through local subcontractors without taking ownership of additional land.

Choosing where to locate manufacturing operations requires that management compare countries on multiple criteria. Beyond the obvious issues of market size, economic regulations, political stability, and sustained commitment to reforms, other criteria include:

- Predictability and costs of distribution to move raw materials to and finished product from the production site. Longer lead times and higher inventory holding costs are necessary when distribution is problematic.

- Consistent availability of basic services such as water and electricity. Few other African countries have the hydroelectric capacity of Zaire and Equatorial Guinea, although administrative problems or political disorder can disrupt service. The generally weak telecommunication infrastructure is also critical. For example, it is so deficient in Zaire that people have resorted to using walkie-talkies rather than the unreliable telephone system. Other countries, such as nearby Kenya, have much better service.

- Currency stability and convertibility. Foreign exchange remains a scarce resource for most sub-Saharan countries, so it is controlled by the government. In West Africa, the CFA franc, accepted as legal tender in six countries and easily convertible with the French franc, facilitates foreign exchange transactions. However, being tied to the franc can cause the local currency to become overvalued, creating problems for exporters.

- Variation in labor costs and skills. For example, labor rates in Côte d’Ivoire are thirty times those in Nigeria and five times those in Ghana. Obligatory social benefits and worker productivity rates can also vary significantly.

- Investment incentives. When, in 1986, a new minerals code caused gold production in Ghana to double, the biggest contributor was Ashanti Goldfelds, 45 percent owned by Lonrho, the British conglomerate.14

- Track record. Fifty U.S. MNCs have established operations in Côte d’Ivoire, whereas in neighboring Senegal, the Dakar Industrial Free Trade Zone, established in 1974, has attracted little MNC interest.

By choice or in response to government regulation, many MNCs are involved in joint ventures with local businesses or governments, especially in the larger markets where they have manufacturing operations. H.J. Heinz saw its joint venture with the Zimbabwean government as enabling it to better understand the rules and regulations governing that society. Companies doing business in sectors of the economy such as financial services that are subject to government regulation have to be especially flexible in structuring their business entities in African countries. AIG insurance, for example, has three quite different arrangements in its principal African markets:

- In Nigeria, AIG owns 40 percent of its operation. Three Nigerian states own eleven percent, and 3,000 Nigerians own forty-nine percent as a result of the company listing on the stock exchange.

- In Kenya, AIG owns 67 percent, while a local bank owns the remaining third.

- In Uganda, AIG owns 51 percent, while the government owns 49 percent.

A government parastatal owned 45 percent of Unilever’s Kenyan subsidiary, East African Industries. It is now divesting itself of the shares as part of the government’s privatization process.

Joint ventures in which governments have a stake are considered less subject to adverse legislation. However, Citibank has tried to avoid them. Of twelve subsidiaries in Africa, only one (in Nigeria) is not wholly owned, even though the host government is often Citibank’s major customer for short-term financing services.

The availability of private, nongovernment, joint venture partners or licensees is improving. Typical is the Fakhry Group in Côte d’Ivoire, a private family-owned holding company that now owns a construction firm, a freight-forwarding business, a supermarket chain, and factories making T-shirts and blue jeans.15 The jeans company, Challenger, was launched when Fakhry licensed the Wrangler name in 14 West African countries and acquired Wrangler’s plant with its well-trained labor after the U.S. owner decided to shift from direct production to licensing. Challenger manufacturing capability allows it to change its product line quickly, responding to the latest European fashions. This has earned it a niche as a quick-delivery, low-cost supplier to European distributors. Additionally, it has positioned itself in the West African market as a supplier of high-status jeans priced below the market leader, Levi Strauss.

Fakhry’s successful involvement in manufacturing is not yet typical. Many local entrepreneurs are attracted by the lower risk and quicker profits offered by trading and distribution compared to manufacturing. Partly as a result, for example, the Nigerian government is investing in demonstration manufacturing projects using local raw materials; once viable, local investors will buy the plants as sole owners or majority partners in joint ventures.

Marketing and Organization

A minority of MNCs have a long-standing tradition of marketing in Africa. Colgate-Palmolive Co., for example, has had a presence since 1929. In 1992, it employed some 3,000 people, had its own operations in twenty-two African countries including plants in ten, sold its products in a further twenty countries, and generated $300 million in annual sales. As a result of experience, a persistent presence through good times and bad, strong financial controls, and good government relations, Colgate’s African operations are consistently profitable.

How do companies like Colgate that are successfully marketing in Africa respond to the challenges and opportunities of the region? The following sections attempt to answer that question.

Product Policy

Since the African continent in total represents a small market opportunity, most MNCs offer a selection of basic, versatile products, without local adaptation, from among the product lines they sell in the developed world. Johnson & Johnson, for example, has found that its multipurpose petroleum jelly for moisturizing dry skin is an especially strong seller.

Other companies find that their mix of business is different and that adaptation is necessary. Half of AIG’s business in the developed world comes from personal insurance sales, but in Africa, only 15 percent of its sales are from this source. Personal life insurance policies tend to be short-term endowment policies used as savings vehicles and are marketable only in countries with moderate inflation. Reader’s Digest adapts 20 percent of its editorial material for its African regional edition published in South Africa and substitutes African photography, where appropriate, to accompany the other 80 percent. Other companies manufacture in African plants products that are especially designed to meet African consumer preferences. Colgate-Palmolive, for example, makes and markets Protex antibacterial soap — in the shape of a ball rather than a bar — and Axion detergent paste only in Africa.

Industrial marketers that do little or no manufacturing in Africa do not usually adapt their products. User skill levels are such, however, that the best equipment to sell is that which is highly durable and reliable in harsh environments and, at the same time, easy to operate and easy to repair if necessary. Selling equipment with bells and whistles of marginal importance to the basic functionality of the product may do more harm than good. One Kenyan printing company chose to buy mechanical rather than electronic printing equipment because there was no local repair capability for the more sophisticated electronic equipment. IBM, which sells its products in twenty-nine African countries, does not adapt its hardware, but does adapt its software. IBM’s “Guide to Software for Developing Countries” documents special programs on customs and excise control in multiple languages. IBM also operates Data Service Centers where African small businesspeople can run their own software on IBM hardware at relatively low cost. For its larger customers, especially other MNCs, IBM’s major challenge in Africa is to deliver a level of service through small national offices that is equivalent to that expected and delivered in the developed world.

Because buyers are concerned about breakdowns and after-sales service, there is a widespread inclination to pay price premiums for well-known brands of industrial goods sold with value-added technical service and support in preference to low-price generic knock-offs from China or Hungary, for example. This is especially so in the case of industrial equipment purchased for projects financed by international aid and development organizations. Consumers in African countries, especially younger, urban residents, also tend to be aware of and loyal to well-known Western brands, even in the case of packaged goods that would be regarded as low involvement and subject to high private-label penetration in the developed world. Some brand names have become so well-known that they are used as generic terms for the category; Colgate, for example, is the generic term for toothpaste for many African consumers. When Unilever introduced its competing Close-Up brand toothpaste, consumers referred to it as the “Red Colgate.” As a result of long-standing selling efforts, brands from companies based in each country’s former colonial power retain dominance; for example, French brands of cigarettes are dominant in West Africa while British brands are strongest in East and South Africa. Branded products will not automatically succeed when transferred from one African country to another due to important differences in consumer preferences. One leading brand of solid cooking fats in Kenya did not sell well in Nigeria because of Nigerians’ preference for liquid cooking oil. A leading detergent softener in Zimbabwe flopped in Kenya because the consumers preferred a different viscosity and perfume.

Some consumer goods companies offer similar pack sizes to those used in the West. Coca-Cola Company uses only twelve-ounce glass bottles, all of which are returnable; recyclable bottles reduce Coke’s dependence on glass bottle imports or the raw materials to manufacture them locally. In the case of packaged goods companies offering multiple pack sizes, relative demand for each is driven by disposable income rather than household size. Only the well-off minority enjoys the convenience of larger sizes; they are typically available only through urban supermarkets. The smallest pack sizes are usually the best sellers, and in many countries, street hawkers break bulk further by selling, for example, individual tablets of medications or single cigarettes on street corners or through roadside stands.

Marketers must remember that the product turnover rate, especially in rural outlets, is slow. Without adding cost, packaging must be robust enough to protect products from heat and other poor storage conditions for long periods before they are sold to consumers. There have been packaging shifts, particularly from tin to plastic, in response to cost differentials and consumer preferences.

Storage conditions also influence the mix of products that companies can sell successfully. Coca-Cola Company’s Fanta brand orange drink outsells Coca-Cola in some poorer African countries where refrigeration is less available because the orange flavor is both more familiar and more appealing when warm than a warm Coca-Cola. There are further consequences of the lack of refrigerated storage. Diet Coke is not marketed outside the tourist areas, not only because calorie consciousness is irrelevant to African consumers but also because the aspartame in the drink breaks down in sustained heat. Margarine has a longer shelf life than butter, and sterilized milk packaged in Tetra-Pak containers has a multimonth shelf life.

Distribution Policy

Most western goods are not manufactured in the African country in which they are sold but are imported from European plants or, in the case of some simple consumer goods and textile products, from other African countries. Typically, an MNC will appoint an exclusive distributor in each market or enter into one or more distribution agreements, covering a subregion of several small country markets. Whom to appoint as distributor is critical. It is important to check references and consult noncompeting MNCs, local banks, and the local U.S. embassy. Efficient customs clearance and forwarding capabilities are essential. Any agreement must include a clearcut performance-based exit clause, along with the requirement that all shipments be paid for on an irrevocable letter-of-credit basis.16 Patient research is essential since the first distributors to appear (especially those proactively offering their services) are often of questionable ethics and effectiveness in either securing necessary import permits or developing and sustaining customer relationships.

Rarely can an African distributor supply the same service as the MNC would expect its clients to receive in the United States or Europe. Hence, several MNCs, such as IBM and Nalco, have their own missionary salespeople and service technicians working in association with local distributors whose functions are often confined to the distribution of products. The unpredictability of obtaining import licenses and delays in shipments reaching their final destinations from ports of entry often impair the delivery of customer orders. However, better road and rail links offering more choice and, hence, lower costs are promised in southern Africa now that peace is returning to Mozambique and Angola. Customers accustomed to long delays have learned to place early orders. Several Japanese auto companies maintain container ships full of cars and light trucks year-round in international waters off the East African coast; this permits a dealer’s order in any one country to be filled quickly and reduces the manufacturer’s financial risk of having valuable inventory in countries of uncertain stability.

The main distribution challenge for consumer goods marketers is to ensure product availability in the fragmented and undercapitalized distribution systems that characterize African countries. Among the objectives in Coca-Cola Company’s “Three A” African strategy of availability, affordability, and acceptability, the principal challenge is the first. Coca-Cola believes that it could sell much more than it currently does if it could increase bottler capacity and distribution penetration. Coca-Cola also finds expanded availability impeded by a periodic lack of capital that can prevent new bottling plants from being built.

To achieve expanded distribution and greater push by its retailers, Unilever in Kenya uses the following four approaches:

- Distributors must pay a monthly minimum for the right to distribute Unilever products.

- Each distributor has to purchase a minimum quantity of Unilever goods each month to retain distributor status.

- Unilever has the right to impose non-ordered goods, to which it retains title, on its distributors (with the objective of, for example, increasing push for a new product).

- Unilever’s salespeople sometimes employ an “uplifting” program whereby they buy merchandise en bloc from distributors and resell it themselves to local retailers.

MNCs use several additional techniques to achieve distribution in rural areas, where 71 percent of the population resides. Colgate-Palmolive and Johnson & Johnson both use van rancheros to carry their products to rural areas; a loudspeaker on the van announces its arrival to the locals. Coca-Cola subsidizes ice chests and small refrigerators in rural stores so customers can buy cold Coke.

MNCs have to be increasingly sensitive to the role of ethnic groups in the distribution channels. For example, in West Africa, immigrant Lebanese and Greek traders have become increasingly important, and in East Africa, distributors of Asian descent often dominate. One tobacco company achieved good distribution in Senegal by working through a team of Mauritanian distributors on sixty-day cash terms. When a border dispute forced all the Mauritanians living in Senegal to flee, the company was able to reestablish its distribution through daily cash sales at the factory gate to Senegalese small businesses.

Pricing Policy

Selling in Africa requires adjustments to most companies’ pricing structures. First, MNCs marketing locally manufactured goods may find that the benefit of lower labor costs is offset by higher costs for other raw material inputs, especially if they have to secure them from a government-controlled monopoly or, alternatively, import them. This often means that extra inventories are needed in case they cannot obtain import licenses. Second, distributors and business customers purchase in smaller volumes than in the West, so a quantity discount structure offering price breaks at lower volume levels must be developed. Third, business customers often have cash flow problems that render financing and delayed payment programs especially important. Cargill and other multinational agricultural companies provide farmers with financing but require them to have a bank account through which monthly loan payments are remitted automatically to the lender. Fourth, MNCs marketing less sophisticated products are likely to encounter an unexpected mix of competitors that often includes third-world multinationals for whom Africa represents a more important export market than for developed country MNCs17, foreign government agencies seeking to dump excess capacity at rock-bottom prices, plus local entrepreneurs with low overheads as well as counterfeiters of branded products operating in the informal barter economy. On the other hand, in many African countries, Citibank faces little competition even on the basic loans and letters of credit and, based on years of experience in selecting which risks to accept, makes good profits on six percent spreads between average loan and deposit rates.

Despite a deteriorating transportation infrastructure in Africa, gray marketing (transshipment of goods purchased in a low-priced market to a high-priced one) and smuggling are prevalent, particularly in the case of low bulk-to-value products such as cigarettes, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Economic volatility, high tariff barriers, and rapid currency swings make gray marketing both feasible and attractive to Lebanese and Asian expatriate traders. The small West African country of Togo, for example, has long been a point from which distributors smuggle goods into Nigeria.

Government price controls are less common and less broadly applied today than a decade ago; they are more likely to appear in French- than in English-speaking African countries. There are fewer controls on consumer goods (except on the best-known, highly visible brands) than on strategically important industrial goods and services such as computers, bank lending, and insurance rates. Where price controls are present, most MNCs try to negotiate price increases to ensure that they can maintain contribution margins in case price controls are imposed or inflation grows more rapidly than expected. If the company is marketing basic goods, the government resists authorizing price increases due to their political sensitivity. Fixed prices in the face of rising production costs often puts an MNC in a negative margin situation, which is what Unilever’s East African Industries encountered in 1992 in Kenya.

Government regulations sometimes require artificial inflation rather than deflation of MNC prices. In Nigeria, Kenya, and Zimbabwe, AIG must place about 20 percent of its business with a government-owned reinsurer that exacts excessive margins. Local insurers, however, are allowed to use cheaper, offshore reinsurers for all their business so the government regulation is, in effect, both a tax on AIG and a mechanism to protect local business.

Communications Policy

The communications mix that MNCs use in African countries is a function of three principal factors: the household penetration of various advertising media; the relative importance of trial versus repeat purchases; and the availability of and ability to execute different sales promotion techniques.

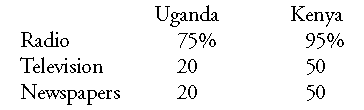

Media penetration varies widely from country to country, as a function of the stage of economic development, literacy rates, urbanization, and level of government control. The spectrum of differences in the region is large: GDP per capita from $80 in Mozambique to $2,530 in South Africa; adult illiteracy from 20 percent in Madagascar to 82 percent in Burkina Faso; urbanization from 6 percent in Burundi to 60 percent in South Africa.18 These are the household penetration levels for three media in the adjacent countries of Uganda and Kenya:

Some MNCs such as Coca-Cola use television advertising on a limited basis not only because of the modest household penetration but also because a high percentage of sets are black and white and, therefore, not very powerful in conveying image-building advertising. In some countries, newspaper advertising is underdeveloped except as a vehicle for employment openings and government notices. Consumer goods MNCs find that radio is the most popular medium. Even though they may have to produce commercials in multiple languages, they can develop locally tailored ads cheaply to incorporate the basic brand benefit message that most marketers need to communicate, thus achieving the highest household reach of any medium. Another important advertising medium is the loudspeakers on the van rancheros that distribute products to rural areas and small towns.

Advertising managers must, as always, consider carefully the cultural values, traditions, and aspirations of the target group. Coca-Cola advertising, for example, often shows the beverage being consumed not on a free-standing basis but rather in conjunction with meals shared by large groups of family members. Standard Chartered Bank, faced with the challenge of persuading blacks to use its automatic teller machines in Zimbabwe, developed a campaign based not on the functional benefits of the technology but on the social status implicit in being able to use it. Another campaign, this time by a bank in Côte d’Ivoire, claimed effectively: “We offer customers the wisdom of the old world combined with the technology of the new.” MNCs operating in Africa may find this kind of balanced approach particularly appropriate in their advertising appeals.

Many types of sales promotion are not practicable in Africa. Some companies have tried couponing, but redemption through retailers is hard to implement and misredemptions are high. However, they do use trial-oriented sampling programs through stores and radio contests. Colgate-Palmolive distributes samples of toothpaste and toothbrushes to students and provides programs that teach them how to brush their teeth. Colgate also organizes movie trucks that visit rural towns and show open-air movies in exchange for a toothpaste carton or a soap bar wrapper. Coca-Cola is investing in sponsorships of sports teams in several larger African countries.

Business-to-business marketers use little advertising, even less in French- than English-speaking Africa. However, merchandising brochures are important and should be of high quality, especially in the more developed African countries. Business marketers typically find that personal selling coupled with demonstrations and/or trials are especially effective. Video presentations and participation in commercial fairs, sponsored by national governments or U.S. embassies, are also helpful.

Organization

MNCs incorporate their African operations into their organization structures in varying ways. A common option is to have a vice president in charge of Africa and the Middle East who reports to the head of the European division. The vice president is usually not located in the region but rather at the MNC’s European headquarters or in a European city such as Geneva or Rome with particularly good flight connections to the region and where the principal international aid organizations serving the region are also headquartered. An exception is Johnson & Johnson’s VP in charge of Africa and the Middle East. Though now reporting to the head of Europe rather than Asia as he used to, he is located not at European headquarters but at world headquarters in the United States. From there, with the aid of fax communications, he can oversee twelve country managers in Africa, tap into the expertise of the world headquarters staff, and raise his region’s visibility at corporate headquarters. Typical of many MNC vice presidents in charge of Africa, he has held the position for more than a decade and has therefore developed a specialist’s knowledge of the region.

MNCs with a more substantial presence in Africa tend to divide the continent into subregions, often based on language and cultural tradition. For example:

- Colgate-Palmolive’s Paris office handles the predominantly French-speaking countries of North and West Africa, while country operations from Rwanda to South Africa are run out of Johannesburg. Other companies that retain operations in South Africa, such as Nalco and Cargill, also run sub-Saharan Africa from there, since South Africa is invariably the principal market in their portfolios.

- IBM’s Southern Europe, Middle East, and Africa (SEMA) division based in Rome oversees IBM branch offices in eastern and southern Africa; these offices handle only service, while autonomous local distributors handle sales. In West Africa, IBM’s four branch offices, responsible for sales as well as service, report to Paris, which also oversees sales in other former French colonies and departments such as French Polynesia.19

- Coca-Cola runs its African operations from England. Four managers of larger country markets (Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Zimbabwe — in three of which Coca-Cola manufactures concentrate) each oversee subregions of the continent as well. Sales volumes in many African countries are insufficient to warrant appointment of a country manager, while in other countries, political volatility makes such assignments unattractive to expatriates. In these cases, the subregion managers oversee local distributors.

- AIG divides its African business between property and casualty insurance, which a president for Africa and the Middle East based in New York headquarters oversees, and life insurance, which a Lebanese based in Cyprus is in charge of.

In Africa, most MNCs appoint young British, French, or American managers with an international perspective, an entrepreneurial spirit, a strong finance background, and general management potential as country managers. They usually compensate them on the basis of sales, profitability, and, unusually important, collection of receivables. Except for the largest markets, MNC country managers in Africa are typically in their first general management positions and are responsible for a modest sales volume; a typical Colgate-Palmolive country manager in charge of Kenya, for example, would be responsible for a unit generating about $20 million in annual sales.

Frequent turnover of those occupying country manager positions is inadvisable because success in Africa depends greatly on personal relationships with buyers. One country manager stated: “Local customers will often think, ‘A multinational is so big, why should I pay my bills? They can afford it.’ As a country manager, you have to instill in your customers that they owe you as an individual rather than the company.”

For decades, some companies, such as IBM and Citibank, have made a sustained effort to train and develop black managers and have evaluated their senior white managers in the region partly on their effectiveness in doing so. The MNCs are able to attract high-quality locals because of the perceived prestige of working for such companies. For example, African executives head East African Industries and Barclay’s Bank in Kenya. In Citibank’s case, several have become country managers in their own or other African countries. Others have moved on to senior positions in the international bank, particularly in the credit area, because of the tight financial control habits that they had to develop to succeed in Africa. Still others have entered government service in their home countries and become cabinet members or senior central bank officials, giving Citibank excellent access to top-level public policy-makers. The training also has played a critical role at lower levels. After Mozambique’s independence, the Portuguese multinational, Grupo Entreposto, launched a massive national program to train auto mechanics and technicians to staff its car dealerships as well as assume managerial positions.

Some MNCs, however, have cited difficulties in human resource development of blacks, particularly in South Africa. Ethnic rivalries within a country can impede the effectiveness of managers of one group in supervising or doing business with members of other ethnic groups. MNCs are uniquely positioned to serve as socially neutral institutions in which different groups can be integrated together in a common purpose, thereby enhancing social unity.

Corporate Responsibility

Whether and how to retain a marketing presence in South Africa are important dilemmas, but by no means the only ones confronting MNCs doing business in Africa. Following the U.S. imposition of economic sanctions in 1986, many U.S. MNCs divested their holdings in South Africa, but in such a way that they could still service existing customers and make new products available to the market. AIG, for example, divested its South African company in 1987 but continues to provide reinsurance to the autonomous local company; AIG now acts, therefore, in the role of wholesaler rather than retailer. Likewise, IBM sold its South African subsidiary to Information Services Management (ISM), a trust created for the benefit of former South African employees of IBM of all races. ISM is the sole marketer of IBM products in South Africa.20

High-profile companies like IBM that sell a large percentage of their total volume to government agencies have to be especially sensitive to being seen as good corporate citizens. IBM therefore supports many government- and development agency-sponsored projects throughout Africa, particularly those that help to develop small businesses and local entrepreneurship. Between 1985 and 1992, for example, IBM contributed $21 million to its South African Projects Fund, which supports economic development, legal reform, and education programs to benefit black South Africans. Coca-Cola Company provides similar support; good government and community relations are essential to secure import licenses for concentrate and to reduce the likelihood of price controls. Coca-Cola works hard to demonstrate to government officials how a multiplier effect means that every dollar allocated to an import license for cola concentrate creates five to six dollars in the local economy. Unilever and Colgate-Palmolive, meanwhile, work hard to develop local sources of chemicals and packaging materials of consistent quality. And the MNCs play an important role in developing human resources through their company training programs.

MNC managers frequently encounter ethical dilemmas or social issues that are not uncommon in the developed world. For example:

- Cash crops such as Del Monte pineapples grown in the rich coastal lands of Kenya generate valuable foreign exchange earnings for the country. However, the result is that less land is available for subsistence agriculture to support those Kenyans living in the region, now among the poorest in Kenya.

- Ciba-Geigy launched an antimalarial drug in Nigeria called Fevex. The company had to weigh the life-saving consequences of broad over-the-counter distribution against the possibility that children might die from accidental overdose.

- A large seed producer was asked by the government to launch a family planning program among its employees to help lower the country’s exceptionally high birth rate, with the added benefit of reducing worker absence and turnover due to pregnancies.

- The Mozambican government asked the Portuguese multinational Entreposto to train small farmers in new production technologies because the government’s capabilities and resources for agricultural extension were inadequate.

Conclusion

The size of Africa’s economic pie is relatively small. The strategic question for multinationals as they look at their global portfolio is not whether they should be in Africa, but rather when, where, and how. The opportunities for MNCs to increase trade with Africa and to exploit low-cost manufacturing as well as marketing opportunities are improving. There are proven first-mover advantages. And a multitude of MNCs are already present. Export, licensing, and even production opportunities exist for medium-size firms too.

The attractiveness of Africa depends significantly on whether the economic reforms and democratization now underway are sustained and on whether political reform in South Africa will allow it to assume a catalytic role in the continent’s economy. Firms must recognize that Africa’s lower level of economic development creates not only a series of distinctive operating problems and challenges, but also significant needs and opportunities. Products, services, and management techniques that have matured elsewhere can find new life in these young and untapped markets. But one should not dabble in Africa. Rewards will come to those who make a serious, long-term commitment. For MNCs, Africa represents, in many respects, the last frontier, to be ignored only at their own competitive peril.

References

1. G.M. Feldman, “Sub-Saharan Africa: Economic Reforms Are at a Critical Crossroads in 1992,” Business America, 6 April 1992, pp. 37–41.

2. International Monetary Fund data base.

3. World Bank, World Development Report 1992 (Washington, D.C., 1992), p. 269.

4. Ibid. p. 265.

5. B. Weimer, “The Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC): Past and Future,” Africa Insight 21 (1991): 78–88.

6. J. Cantwell, “Foreign Multinationals and Industrial Development in Africa” (Reading, England: University of Reading Dept. of Economics, Discussion Paper No. 131, August 1989).

7. F. Williams, “Developing Countries Look for Better Deal on Trade,” Financial Times, 21 May 1992, p. 6.

8. R.J. Barnet, “But What About Africa?,” Harper’s Magazine, May 1990, pp. 43–51; and

M. Prowse, “Poor Nations Accuse the Rich of Breaking Their Own Rules,” Financial Times, 30 April 1992, p. 6.

9.“Controversy Over African Aid Simmers,” Africa News, 7 October 1991, p. 3.

10. “Democracy in Africa: Lighter Continent,” The Economist, 22 February 1992, pp. 17–20.

11. “USA/Africa: Policy? What Policy?” Africa Confidential, 11 January 1991, pp. 1–4.

12. A. Rusinga, “The Drive To Upgrade Transport,” Africa South, June 1991, pp. 25–33.

13. World Development Report 1992, p. 223.

14. K. Gooding, “Ghana Points the Way Along Africa’s Golden Road,” Financial Times, 28 July 1992.

15. J.E. Austin and M. Grossman, “African Enterprises: The Search for Success” (Boston: Harvard Business School, Research Project Working Document, 1992).

16. Deep devaluations in local currencies invariably limit a distributor’s ability to continue to obtain letters of credit through no fault of its own.

17. Indian foreign direct investments in Nigeria, for example, are greater than in any other country.

18. World Development Report 1992, pp. 278–279.

19. In the same vein, many MNCs place the country manager of Portugal in charge of sales in the former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique.

20. B. Bremner, “Doing the Right Thing in South Africa?” Business Week, 27 April 1992, pp. 60–64.