The Art of Making Smart Big Moves

For many companies, incremental growth is not sufficient. The changing business landscape is forcing corporate leaders to learn how to reposition their businesses more fundamentally.

Companies make big moves when they change direction with a large commitment of resources. These moves typically involve a different set of products or services, a new customer base or new ways of operating. Nokia Corp.’s shift in the early 1990s from forestry, TVs and tires to mobile phones is an example of a big move. Such strategic shifts are risky — companies that attempt them often fail to meet their stated objectives. Yet they are essential for value creation in the long run. Although companies may have long periods of incremental growth, the constantly changing business environment periodically forces corporate leaders to reposition their businesses in fundamental ways.

Our interest in studying big moves — specifically, why some companies succeed in making smart big moves while others fail — was triggered by longitudinal case studies conducted by us as well as by other researchers.1 These case studies included some big moves that were industry firsts and others that were in response to industry or macroeconomic shifts or to company-specific problems. The case studies suggested a number of hypotheses, which we first tested in the executive classroom and then more systematically on 24 multinational companies. (See “About the Research.”)

In some respects, our findings were predictable. Companies that launched successful big moves used sound strategic thinking: They exploited and in some instances enhanced their distinctiveness relative to their competitors, and they built on an existing repertoire of managerial and business experience. However, our most interesting discovery had to do with what we refer to as “complementarity.” The more successful companies followed a consistent learning logic both internally and externally with respect to innovation, efficiency and customer intimacy, and the most successful companies made big moves that were complementary over time. As a rule, complementarity plays out in three ways: (1) It builds on a dominant, successful business model; (2) it relies on periodic shifts in the balance between innovation, efficiency and customer intimacy when the business model is not working; and (3) it promotes a sequenced development of capabilities when the balance shifts. Together, these elements make up a learning logic that supports companies as they make important strategic shifts.

If the Business Model Is Successful, Stay With It

The first thing executives need to recognize is that the safest big moves build on business models that are already working.2 Radically changing the value proposition is riskier than acquiring new customers. So if the business model ain’t broke, don’t fix it—roll it out. It is better to go for a larger share of market among existing customers or to extend the portfolio of valuable customers with new customers, new geographies or digestible acquisitions.

This is what food and household giant Unilever did with its Lipton Foods brand when it applied its successful hot tea business model to the ready-to-drink tea market in the late 1990s. Lipton’s tea division was twice as big as its closest competitor, R. Twining and Company, Ltd., and was still gaining market share with its existing customers as they migrated from loose tea to tea bags. But as far as Lipton was concerned, the market was not just the tea business but the global, branded beverage industry. In an effort to sell against giants such as the Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc., it went after new customers in new markets (for example, pitching iced tea as an alternative for coffee drinkers).

This strategy is similar to Nokia’s when that company brought its innovative phones to new markets in Europe and Asia during the 1990s. Its success was built on rolling out the basic business model that CEO Jorma Ollila defined in 1992: telecom-oriented, global, focused and value-adding. Not only did Nokia expand into new markets, it also kept adding to its product line, wooing customers in different segments and encouraging users to upgrade their phones whenever there were new features. Nokia stayed at the forefront of incremental innovation, shortening product cycles and launching new models just as margins on existing models dropped. By 1998, Nokia was selling three out of every 10 mobile phones and had overtaken Motorola Inc. as the world’s largest mobile phone maker.

As Nokia moved to expand its set of valuable customers, Tele-fonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson tried to make its operations more efficient, struggling with its engineering-oriented business model. Ericsson changed CEOs twice in the course of 10 years, initiated a massive restructuring program and faced increasing negative cash flow thanks to bulging inventory and an inability to refresh its products. While Nokia was successful at reinforcing what it had done, Ericsson didn’t realize when it was time to change the model.

Be Prepared to Shift the Balance

The second thing executives need to understand about successful big moves is that these moves require management to realign the balance between innovation, efficiency and customer intimacy capabilities. While each of these forces needs to be at work at all times, it is difficult to pursue them with equal intensity. Companies need to shift the focus of their resources depending on their current business and financial needs. For example, innovation typically calls for a looser organization with room for experimentation, entrepreneurship and flexible resources. Efficiency depends on greater coordination, leveraging activities in the business system and removing slack from the organization. And customer intimacy requires a culture of listening and networking with resources directed at building relationships with customers.

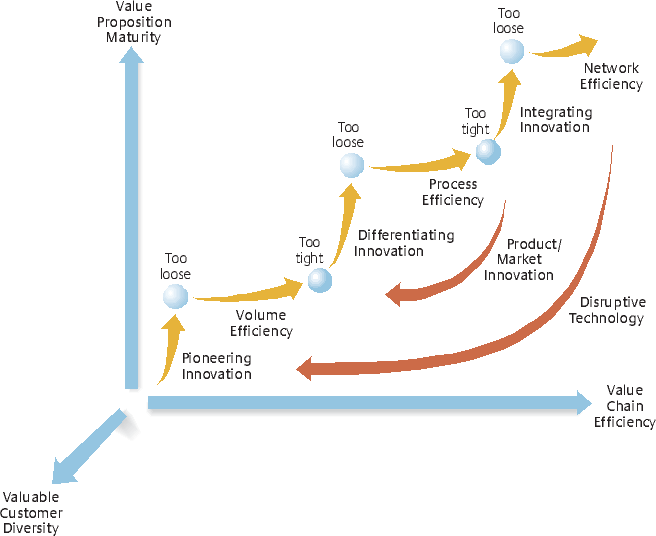

A typical cycle might involve loosening the organization to stimulate top-line growth through innovation, followed by the need to tighten the organization to improve margins, followed by the need to get closer to customers again to find out what kinds of innovation they want in future products or solutions. (See “The Shifting Balance of Capabilities.”)

This process can be illustrated by examining Nokia’s big strategic moves over the last 15 years. During this time, there were two periods when management emphasized efficiency; each was followed by a period when management emphasized innovation. In the early 1990s, cost cutting by CEO Simo Vuorilehto provided the financial resources that enabled the company to introduce its mobile phones. However, this pioneering phase soon ran into problems: Increasing costs from inadequate logistics, quality control and budgeting triggered a shift away from innovation toward efficiency. The subsequent drive for process efficiency in turn provided the operating basis for a new growth period during the late 1990s based on increased attention to customers and differentiating innovation.

In the car industry, both the BMW Group and Daimler-Benz AG attempted to grow at different times by broadening their product offerings through acquiring the Rover Group and Chrysler Corp., respectively. But both companies ran into integration problems, forcing them to redirect their emphasis toward efficiency. (BMW sold most Rover brands in 2000, retaining the MINI; Daimler-Benz managed to turn around Chrysler and is now DaimlerChrysler.) Once efficiency was back on track, the companies again shifted their emphasis, this time to innovation in the form of new model development.

Sequence the Development of Capabilities

The third thing executives need to keep in mind about big moves is that the capabilities needed to balance innovation, efficiency and customer intimacy will change as their value proposition matures. (See “The Capabilities Sequence.”) Competitors that miss or skip stages in the learning logic often run into difficulties. When power and automation technology provider ABB Asea Brown Boveri Ltd., headquartered in Zurich, Switzerland, tried to move from differentiating innovation to solutions innovation without going through process efficiency, for example, the company couldn’t deliver and incurred large cost overruns. The process efficiency step would have involved standardizing its 700-plus computer systems to build the efficiency necessary to offer global solutions to its clients.

In a sequence of smart big moves in the 1990s, Nokia relied on pioneering innovation to enter the mobile phone market, on process efficiency to lower costs and on differentiating innovation to attract new retail customers; it subsequently began integrating innovation to develop customized solutions for its corporate clients. By the end of the decade, Nokia’s brand recognition was among the best in the world. From 1995 to 2000, its market value had increased 28 times to $210 billion.

Like Nokia, Ericsson’s trajectory went through the pioneering innovation and process efficiency stages with its second-generation GSM (global system for mobile communications) phones. However, its trajectory soon diverged from Nokia’s. While Nokia created variety in its value proposition with differentiation, Ericsson attempted to extend its market position based on volume efficiency, which limited its available resources for innovation. Its rigid structure and engineering-dominated culture also made it difficult to create a more entrepreneurial organization and to meet the demand for more variety; its sales people did not know how to acquire new market segments. In addition, it was unable to increase efficiency with process improvement, partly because the corporate structure was organized around strong country and functional heads. Without further gains in efficiency, it could not continue to compete based on lower costs.

In 2001, Ericsson announced the largest loss in Swedish corporate history; its market capitalization had dropped from $131 billion at the height of the dot-com boom to $11 billion at the end of 2002, and its share of the mobile phone market fell from 20 % to less than 5 %. Ericsson needed to adopt a new business model in response to emerging technologies but, given its organizational rigidity, it was unable to respond. The only silver lining was that its nemesis, Nokia, was struggling with its own problems.

Nobody Has a Monopoly on Smart Big Moves

A company’s learning logic can be interrupted at any moment by external events — for example, the emergence of a new product market segment, a new disruptive technology or another event originating outside the industry. When this happens, the key success factors change. Incumbents rarely respond successfully because they can’t adapt quickly enough.

Between 2000 and 2002, in the wake of the collapse of the telecom bubble, Nokia’s market value dropped by two-thirds to $76 billion. In response to the convergence of telecoms, computing and consumer electronics, Nokia management elected to redirect the strategic emphasis from differentiation to pioneering. First, they reorganized product and market development in the mobile phone division into eight customer-facing units; then they divided the entire company into four divisions: mobile phones, telecom equipment, business applications and multimedia devices. Unfortunately, the focus on internal reorganization did not lead to pioneering innovation. Instead, it had a negative effect on the rate of new-model introduction.

This partly explains the reversal of fortune that both Nokia and Ericsson experienced from 2002 to 2004: Nokia’s market capitalization declined while Ericsson’s increased. By 2002, Nokia and Ericsson were not just competing with each other; they were also vying with other players such as QUALCOMM Inc. and Samsung Group for control over the next generation of mobile hardware and software platforms. While Nokia was reorganizing to cope with the wave of disruptive technology, competitors were coming to market with innovations like clamshell phones and color screens. In the process, Nokia lost market share. Reorganizing to deal with a breakpoint in the learning logic, it lost focus on existing markets.

As Nokia struggled, Ericsson, in a desperate move to save its mobile phone division, initiated a smart big move — perhaps its best move since the early 1990s. It set up a joint venture with Sony Corp., a company that understood media technology and pioneering innovation as well as any company in the market. With survival on the line, the atmosphere inside the joint venture was very much that of a start-up. Within the first year, Sony Ericsson Mobile Communications AB introduced the T68i mobile phone with color screen, aimed at the top end of the market. The new phone was a hit with consumers, and it was followed by other popular models, including the P800 and P900, which combined phone, e-mail, photo and digital organizer features. As a start-up, Sony Ericsson was able to compete more flexibly than Ericsson had before. Between 2002 and 2004, Ericsson’s market value increased by almost $40 billion, supported both by mobile phones and a large pick-up in telecom infrastructure spending. For its part, Nokia’s market value fell by $5 billion, to $71 billion.

A similar pattern can be observed between Hewlett-Packard Co. and IBM Corp. While IBM was surging ahead with its global information services, HP battled to integrate its acquisition of Compaq in an effort to be both low cost and high tech. It looked as though IBM would be the industry winner, with a gap of almost $100 billion between the two companies. But in 2002, IBM made a successful bid for Pricewater-houseCoopers Consulting and started moving into business-process transformation services. Facing established competitors, it had difficulty positioning itself and integrating the consultants it had acquired. By early 2005, IBM shares had lost almost one-quarter of their peak 2002 value.

Think Smart Before You Think Big

Beyond complementarity, smart big moves are distinctive relative to competition and do not involve jumps into the unknown. But making bold, distinctive moves is easier said than done. It requires ambition and a can-do attitude. Unfortunately, the emotions that drive ambition frequently overpower practical realities: We see what we want to see. To eliminate such blinders, managers need to be brutally honest when examining the business case. This is what BMW’s management did when it decided to sell most of the Rover brands, keeping only the MINI subsidiary, which it repositioned as a sedan with the feel of a sports car.

By contrast, neither IBM’s move into business-process transformation services nor Nokia’s reorganization were distinctive. IBM had difficulty differentiating itself from established competitors, and Nokia’s reorganization turned people inward, causing them to lose focus on the market. Similarly, Ericsson’s repeated attempts to downsize in the late 1990s did little to make its offerings more distinctive; instead, the cuts simply caused more downsizing.

Companies need to invest time in developing new capabilities. Smart big moves shouldn’t be leaps into the unknown but extensions of the company’s existing portfolio or managerial repertoire. Few people would be naïve enough launch a major new product in multiple markets without trying it first in focus groups and test markets. Yet managers make other types of big moves—for example, large-scale reorganizations and huge mergers and acquisitions—without carefully exploring whether they will work. Such “naked” big moves call for deep transformations, involving not only new behaviors but also the ability to reshape the internal and external conditions to support them.

When IBM made the big commitment to global information services, it did so with the experience of an already existing computer services division. When it moved into e-business, it capitalized on an existing frontline initiative. When Nokia moved into mobile phones, it jumped from an existing base: It had real experience in the area it was betting on, and its mobile telecom business was already showing promise in Scandinavia. By contrast, the spin-off of the Ericsson and Sony mobile phone businesses into Sony Ericsson was a leap into the unknown. Although Sony Ericsson has had early successes, the jury is still out on its long-term results.

Smart big moves leverage the company’s previous experience, either in earlier periods, pilot projects or small business units. People should understand the business model, organizational requirements and leadership that are needed. The subtleties of the new capabilities required should be familiar to at least some managers. Those initiating big moves should also be clear on their personal motivations. Once the necessary ingredients are in place, managers should not hesitate to shift resources and decision-making power to the standard bearers of the new direction.

References

1. For example, case studies on ABB (2003) by P. Strebel and N. Govinder; HSBC and Oticon (2005), by P. Strebel and B. Rogers; and Medtronic (2002) and Best Buy (2004) by B. Chakravarthy in “Leading for Growth: Managing Dilemmas” (forthcoming with P. Lorange), all published by IMD, Lausanne, Switzerland.

2. C. Zook, “Beyond the Core: Expand Your Market Without Abandoning Your Roots” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004), 256; and J. Collins “Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t” (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 320.

3. This exhibit originated in work about outpacing strategies done with X. Gilbert and work on breakpoints by P. Strebel. It was also influenced by work on new competitive strategies by A. Boynton and B. Victor. See X. Gilbert and P. Strebel, “Strategies to Outpace the Competition,” Journal of Business Strategy 8 (summer 1988): 28–36; P. Strebel, “Breakpoints: How Managers Exploit Radical Business Change” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1992), chap. 1 and 11; P. Strebel, “Trajectory Management: Leading a Business Over Time” (New York: Wiley, 2003), chap. 4; and B. Victor and A. Boynton, “Invented Here: Maximizing Your Organization’s Internal Growth and Profitability” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998), 255.