The Comparative Advantage of X-Teams

The current environment demands a newbrand of team — one that emphasizes outreach to stakeholders and adapts easily to flatter organizational structures, changing information and increasing complexity.

Often teams that seem to be doing everything right — establishing clear roles and responsibilities, building trust among members, defining goals — nevertheless see their projects fail or get axed. We know one such team that had a highly promising product. But because team members failed to get buy-in from division managers, they saw their project starve for lack of resources. Another group worked well as a team but didn’t gather important competitive information; its product was obsolete before launch.

Why do bad things happen to good teams? Our research suggests that they are too inwardly focused and lacking in flexibility. Successful teams emphasize outreach to stakeholders both inside and outside their companies. Their entrepreneurial focus helps them respond more nimbly than traditional teams to the rapidly changing characteristics of work, technology and customer demands.

These new, externally oriented, adaptive teams, which we call X-teams, are seeing positive results across a wide variety of functions and industries. One such team in the oil business has done an exceptional job of disseminating an innovative method of oil exploration throughout the organization. Sales teams have brought in more revenue. Drug-development teams have been more adept at getting external technology into their companies. Product-development teams have been more innovative — and have been more often on time and on budget.

The current environment — with its flatter organizational structures, interdependence of tasks and teams, constantly revised information and increasing complexity — requires a networked approach. X-teams have emerged to meet that need. In some cases, they appear spontaneously. In other cases, forward-looking companies have established specific organizational incentives to support X-teams and their high performance levels.

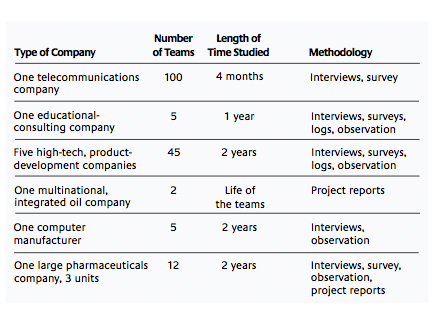

Our studies all support the notion that the rules handed down by best-selling books on high-performing teams need to be revised. (See “About the Research.”) Teams that succeed today don’t merely work well around a conference table or create team spirit. In fact, too much focus inside the team can be fatal. Instead, teams must be able to adapt to the new competitive landscape, as X-teams do. X-teams manage across boundaries — lobbying for resources, connecting to new change initiatives, seeking up-to-date information and linking to other groups inside and outside the company. Research shows that X-teams often outperform their traditional counterparts.1

Five Components That Make X-Teams Successful

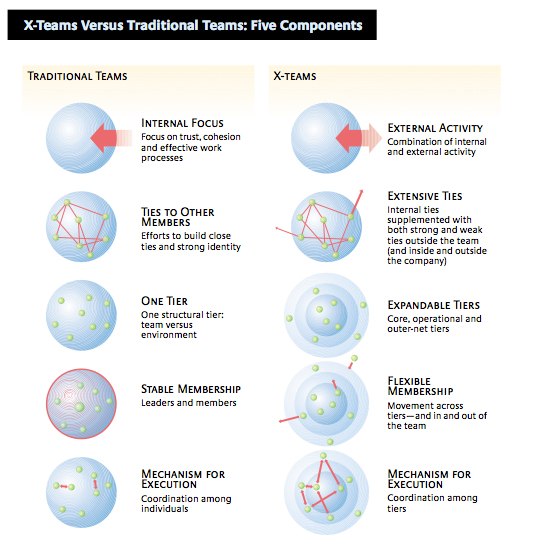

X-teams are set apart from traditional teams by five hallmarks: external activity, extensive ties, expandable structures, flexible membership and internal mechanisms for execution. (See “X-Teams Versus Traditional Teams: Five Components.”)

External Activity The first hallmark of the X-team is members’ external activity.2 Members manage across boundaries, reaching into the political, informational and task-specific structures around them. In some cases, the team leader takes on the outreach; in other cases, it is shared by everyone. High levels of external activity are key, but effectiveness depends on knowing when to use the particular kind called for: ambassadorship, scouting or task coordination.

It doesn’t matter how technically competent a team is if the most relevant competency is the ability to lobby for resources with top management. And even resources mean little without an ability to reach outsiders who have the knowledge and information to help team members apply the resources effectively. Thus at any given time, any X-team member may be conducting one or more of the three external activities.

Ambassadorial activity. Ambassadorial activity is aimed at managing upward — that is, marketing the project and the team to the company power structure, maintaining the team’s reputation, lobbying for resources, and keeping track of allies and competitors. Ambassadorial activity helps the team link its work to key strategic initiatives; and it alerts team members to shifting organizational strategies and political upheaval so that potential threats can be identified and the damage limited.

For example, the leader of what we call the Swallow team wanted to manufacture a new computer using a revolutionary design. The company’s operating committee, however, wanted only a product upgrade. The team leader worked with a key decision maker on the operating committee to portray the benefits of the product to the organization — and eventually got permission for the design. He continued to provide updates on the team’s progress, while keeping tabs on the committee’s key resource-allocation decisions.

Scouting. Scouting activity helps a team gather information located throughout the company and the industry. It involves lateral and downward searches through the organization to understand who has knowledge and expertise. It also means investigating markets, new technologies and competitor activities. Team members in our studies used many different modes of scouting, from the ambitious and expensive (hiring consultants) to the quick and cheap (having a cup of coffee with an old college professor or spending an hour surfing the Internet).

Effective teams monitor how much information they need — for some, extensive scouting early on to get the lay of the land is all that’s needed. For others, scouting continues throughout the life of the team. In particular, teams working with technologies created by outsiders can never relax their scouting activities.

Task coordination. Task-coordinator activity is much more focused than scouting. It’s for managing the lateral connections across functions and the interdependencies with other units. Team members negotiate with other groups, trade their services and get feedback on how well their work meets expectations. Task-coordinator activity involves cajoling and pushing other groups to follow through on commitments so that the team can meet its deadlines and keep work flowing. When the Swallow team needed to check some new components quickly and learned that the testing machine was booked, team members explored swapping times with another team, using the machine at night or using machines elsewhere — whatever it took to keep the work on track.

Extensive Ties In order to engage in such external activity, team members need to have extensive ties with outsiders. Ties that academic researchers call weak ties are good for certain purposes — for example, when teams need to round up handy knowledge and expertise within the company. One team we studied gave a senior position to a new hire straight out of graduate school because of his ties to important experts at prestigious academic institutions. The ties were weak but extensive and contributed immensely to the success of the team’s project.

Strong ties, however, facilitate higher levels of cooperation and the transfer of complex knowledge. Strong ties are most likely to be forged when relationships are critical to both sides and built over long periods of time.3 In the case of Swallow, the team leader’s prior relationship with the operating-committee member helped snare funding for the revolutionary computer design. And the three team members from manufacturing had ties that smoothed the transition from design to production.

Expandable Tiers But how to structure a large, complex team? How to combine the identity and separateness of a team with the dense ties and external interactions needed to accomplish today’s work? Our research shows that X-teams operate through three distinct tiers that create differentiated types of team membership — the core tier, operational tier and outer-net tier — and that members may perform duties within more than one tier.

The core members. The core of the X-team is often, but not always, present at the start of the team. Core members carry the team’s history and identity. While simultaneously coordinating the multiple parts of the team, they create the team strategy and make key decisions. They understand why early decisions were made and can offer a rationale for current decisions and structures. The core is not a management level, however. Core members frequently work beside other members of equal or higher rank, and serve on other X-teams as operational or outer-net members.

The first core member of the Swallow team was the leader; then two senior engineers joined and helped to create the original product design and to choose more members. The core members were committed to the revolutionary computer concept and accepted its risks. They understood how quickly they had to act in order to make an impact on the market. The core members chose more engineers for the team, helped coordinate the work across subgroups, and kept in touch with the company’s operating committee and other groups. They decided when to get feedback from outsiders, and they set up a process to make the critical decisions about how compatible with industry standards to make the design. They organized team social events — and when members had to work long hours to make a deadline, they even brought in beds.

Having multiple people in the core helps keep the team going when one or two core members leave, and it allows a core member who gets involved with operational work to hand off core tasks. Teams that lose all their core members at once take many months to get back on track.

The operational members. The team’s operational members do the ongoing work. Whether that’s designing a computer, creating an academic course or deciding where to drill for oil, the operational members get the job done. They often are tightly connected to one another and to the core (and may include some core members). In the Swallow group, 15 engineers were brought into the operational layer to work on the preliminary design. They made key technical decisions, but each focused on one part of the design and left oversight of the whole to the core.

The outer-net members. Outer-net members often join the team to handle some task that is separable from ongoing work. They may be part-time or part-cycle members, tied barely at all to one another but strongly to the operational or core members. Outer-net members bring specialized expertise, and different individuals may participate in the outer net as the task of the team changes.

For example, when the Swallow team wanted to ensure its initial design made sense to others, it brought in outer-net people from other parts of R&D. For two weeks, the enlarged team met to discuss the design, its potential problems, ideas for changes and solutions for problems that operational members had identified. Then those new members left. Meanwhile, designated members of the core group met weekly with different outer-net members — people from purchasing, diagnostics and marketing — for information sharing, feedback and smoothing the flow of work across groups. Some X-teams’ outer nets also include people from other companies.

The three-tier structure is currently in use at a small, entrepreneurial startup we know — except that the employees there say “pigs,” “chickens” and “cows” to refer to core, operational and outer-net team members. Think about a bacon-and-eggs breakfast. The pig is committed (he’s given his life), the chicken is involved, and the cow provides milk that enhances the meal. The startup’s terms are handy for discussing roles and responsibilities. A person might say, “You don’t need to do that; you’re only a chicken” or “We need this cow to graze here for at least two weeks.”

Flexible Membership X-team membership is fluid.4 People may move in and out of the team during its life or move across layers. In a product-development team similar to Swallow, there was a manufacturing member who shifted from outer-net member to operational member to core member. At first, he was an adviser about components; next he worked on the actual product; then he organized the whole team when it needed to move the product into manufacturing. He became team leader and managed the transition of team members back into engineering as more manufacturing members were brought in.

Mechanisms for Execution An increasing focus on the external context does not mean that the internal team processes are unimportant. In fact, traditional coordination mechanisms such as clear roles and goals may be even more important when team members are communicating externally, membership is changing, and there are different versions of membership. The trick is to avoid getting so internally focused and tied to other team members that external outreach is ignored. X-teams find three different coordination mechanisms especially useful: integrative meetings, transparent decision making and scheduling tools such as shared timelines.

First, through integrative meetings, team members share the external information each has obtained. That helps keep everyone informed and increases the information’s value by making it widely available. The meetings ensure that decisions are based on real-time data from combinations of task-coordinator, scouting and ambassadorial activity.

Second, transparent decision making, which keeps people informed about the reasons behind choices, is good for nudging everyone in the same direction and for maintaining motivation. Even when team members are frustrated that a component they have worked on has been dropped, they appreciate knowing about the change and why it has been made.

Finally, measures such as clearly communicated but flexible deadlines allow members to pace themselves and to coordinate work with others. The just-in-time flexibility allows for deadline shifts and adjustment. If external circumstances change, then work changes and new deadlines are established.

Putting the Pieces Together X-team components form a self-reinforcing system. To engage in high levels of external activity, team members bring to the table outside ties forged in past professional experience. To be responsive to new information and new coordination needs, X-teams have flexible membership and a structure featuring multiple tiers and roles. To handle information and multiple activities, they have coordination mechanisms and a strong core. The five components cannot work in isolation. They complement one another. Although small or new teams may not have all five components, fully developed X-teams usually do.

Supporting X-Teams

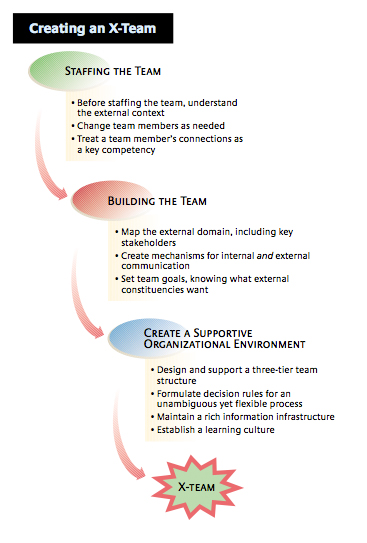

The more dependent a team is on knowledge and resources in its external environment, the more critical is the organizational context. Companies that want high-performing X-teams can create a supportive organizational context — with three-tier structures mandated for teams, explicit decision rules, accessible information and a learning culture. Within a company, it’s generally the organizational unit that sets those parameters, provides resources and lays down rules. (See “Creating an X-Team.”)

A large pharmaceuticals company that we call Pharma Inc. illustrates the importance of such support. One of the authors was asked to investigate a dramatic performance variation among drug-development teams that were working on molecules from external sources. (Such projects are known as in-licensing projects.) A performance assessment showed that the teams of one unit were doing well, the teams of a second unit showed varying results, and the teams of a third unit were doing poorly. To probe the differences, we picked a chronological sequence of three teams at the best-performing site (the Alpha site) and three teams at the worst-performing site (the Omega site) for a careful study.

The story that emerged seemed almost implausibly black-and-white: All the central steps the three Alpha teams took seemed to contribute to positive performance, whereas the opposite was true for the Omega teams. It appeared that despite fluctuating external circumstances, the Omega teams were sticking to a traditional approach that had served them well enough when they worked on internally developed molecules. The Alpha teams, however, were adapting to the changing environment by using an X-team approach, although they didn’t call it that. In the wake of the molecular biology revolution, which has led to increased use of in-licensed molecules, they saw the importance of external activity and extensive ties, and they adapted.

Three-Tier Structure Organizational structure has a profound effect on team behavior. All Alpha-unit teams used a mandated three-tier structure that gave core members oversight of the activities of operational and outer-net team members. Importantly, the roles were not a reflection of organizational hierarchy. Often a core-team member was junior in the organizational structure to an outer-net member.

Having the core team tied to the outer net was particularly helpful when much external technical knowledge was needed quickly. With links already established, a core member could get information from an outer-net member at short notice. The brief time commitment for serving on the outer net gave X-teams access to some of the company’s most sought-after and overbooked functional experts.

The Omega-unit teams, however, used a traditional one-tier structure. In X-team terminology, the Omega teams had only core members. Although that worked well for coordination, it hampered team members’ ability to adapt to changing external demands.

Explicit Decision Rules X-teams favor decision rules that adapt to new circumstances. The Alpha unit’s X-teams, like most product-development teams, used traditional flow charts, but they constantly updated them. Also, they complemented flow charts with decision rules that allowed the charts to become evolving tools rather than constraints. One such rule was that, all things being equal, the search for solid information was more important than speed. It wasn’t that the teams tolerated slackers. In fact, at times speed had to take precedence over information, but it was the team leader’s responsibility to identify when that should occur.

Another rule mandated that whenever important expertise was not available in the time allotted, a team member would be free to bring in additional outer-net members. Such rules allowed for flexibility but spared team members any ambiguity about what to do at important crossroads. Furthermore, the rules gave them the confidence to act on their own and to raise issues needing discussion. For example, it was never wrong for a team member to suggest that a process be stopped because of a lack of important information in that member’s area. Even if the team overruled the request, speaking up on the basis of an explicit decision rule was definitely appropriate.

The Omega unit’s teams, by contrast, used process flow charts quite rigidly and without complementary decision rules. Team members had to stick to the planned process and were allowed little latitude for tweaking the process even when they saw the need. There was no mechanism for making adjustments.

Accessible Information Access to valid, up-to-date information is always critical, but when knowledge is widely dispersed, the information infrastructure becomes even more important. The Alpha unit had processes that supported teams’ need for accessible data. After every project, a report was written detailing important issues and the lessons learned. The store of reports increased over time. In addition, the Alpha unit maintained a “know-who” database, which provided names of experts in various fields and explained the unit’s historical relationship with those experts.

Unfortunately, at Omega, project reports were written only occasionally and contained mainly the results of internal lab tests. And Omega did not have a know-who database at all.

A Learning Culture A useful information infrastructure cannot be established instantly. It has to be nurtured. That’s why Alpha insisted on project reports whether or not the project was considered a success and regardless of time pressures on team members. Alpha also saw to it that past team members conferred with ongoing teams.

Strong recognition from top management at the Alpha unit reinforced the information infrastructure. The relentlessly communicated learning culture not only generated positive performance for any given team, but helped make every team perform better than the previous one.

The Omega unit had no such practices. As a consequence, new teams in that unit generally had to reinvent the wheel.

Is the X-Team for Your Company?

X-teams are particularly valuable in today’s world (many companies already deploy X-teams without calling them that), but they are not for every situation. Their very nature as tools for responding to change makes them hard to manage. The membership of the X-team, the size of the team, the goals and so on keep fluctuating.

In a traditional team, coordination is mostly internal to the team. It involves a clear task and the interaction of a limited number of members. In an X-team, coordination requirements are multiplied severalfold. The X-team’s internal coordination involves more members, more information and more diversity. On top of that are the external-coordination concerns. Executives considering X-teams must be sure the potential benefits are great enough for them to justify the extra challenges.

The IDEO product-development consulting firm thinks they are. IDEO, based in Palo Alto, California, is an example of a company that depends on the innovativeness and agility of its teams. During brainstorming, experts from multiple industries serve as outer-net members soliciting unique information. Team members go forth as “anthropologists” to observe how customers use their products and how the products might be improved. Employees at IDEO also have been busy creating a knowledge-distribution system they call Tool Box, which uses lively demonstrations to communicate learned knowledge and expertise.5

We recommend using an X-team when one or more of three conditions hold true. X-teams are appropriate, first, when organizational structures are flat, spread-out systems with numerous alliances rather than multilevel, centralized hierarchies. Flat organizations force teams to become more entrepreneurial in getting resources and in seeking and maintaining buy-in from stakeholders.6

Second, X-teams are advised when teams are dependent on information that is complex, externally dispersed and rapidly changing. In such cases, it is critical to base decisions on real-time data.7

Third, use X-teams when a team’s task is interwoven with tasks undertaken outside the team. For example, if every new product that a team works on is part of a family of products that others are working on too, teams need to coordinate their activities with what is going on around them.8

Increasingly, modern society is moving in a direction in which all three conditions are routinely true. That’s why we believe that, ready or not, more organizations will have to adopt the X-team as their modus operandi.

References

1. D.L. Gladstein, “Groups in Context: A Model of Tas Group Effectiveness,” Administrative Science Quarterly 29 (December 1984): 499–517; D.G. Ancona and D.F. Caldwell, “Bridging the Boundary: External Activity and Performance in Organizational Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly 37 (December 1992): 634–665; D.G. Ancona and D.F. Caldwell, “Demography and Design: Predictors of New Product Team Performance,” Organization Science 33 (August 1992): 321–341; D.G. Ancona, “Outward Bound: Strategies for Team Survival in an Organization,” Academy of Management Journal 33 (June 1990): 334–365; D.G. Ancona and D.F. Caldwell, “Compose Teams to Assure Successful Boundary Activity,” in “The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior,” ed. E.A. Locke (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), 199–210; D.G. Ancona and K. Kaeufer, “The Outer-Net Team,” working paper, MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2001; and H.M. Bresman, “External Sourcing of Core Technologies and the Architectural Dependency of Teams,” working paper 4215-01, MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, Massachusetts, November 2001.

2. Ancona, “Bridging the Boundary,” 634–665.

3. M.S. Granovetter, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” American Journal of Sociology 78 (May 1973): 360–380; D. Krackhardt, “The Strength of Strong Ties: The Importance of Philos in Organizations,” in “Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form and Action,” eds. N. Nohria and R.G. Eccles (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1992), 216–239; and M.T. Hansen, “The Search-Transfer Problem: The Role of Weak Ties in Sharing Knowledge Across Organization Subunits,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44 (March 1999): 82–111.

4. D.G. Ancona and D.F. Caldwell, “Rethinking Team Composition From the Outside In,” in “Research on Managing Groups and Teams,” ed. D.H. Gruenfeld (Stamford, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1998).

5. R. Sutton and A.B. Hargadon, “Brainstorming Groups in Context: Effectiveness in a Product Design Firm,” Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (December 1996): 685–718.

6. For a recent interpretation of power dynamics in organizations, see G. Yukl, “Use Power Effectively,” in “The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organization Behavior,” ed. E.A. Locke (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), 241–256.

7. Consistent with this logic, John Austin convincingly demonstrated how team members’ knowledge of the location of distributed information has a positive impact on performance. See J.R. Austin, “Knowing What and Whom Other People Know: Linking Transactive Memory with External Connections in Organizational Groups” (Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings, Toronto, August 2000).

8. For an insightful account of how different tasks require different models of team management, see K.M. Eisenhardt and B. Tabrizi, “Accelerating Adaptive Processes: Product Innovation in the Global Computer Industry,” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (March 1995): 84–110.