The Business of Sustainability

Preface and Executive Summary

Sustainability is garnering ever-greater public attention and debate. The subject ranks high on the legislative agendas of most governments; media coverage of the topic has proliferated; and sustainability issues are of increasing concern to humankind.

However, the business implications of sustainability merit greater scrutiny. Will sustainability change the competitive landscape and reshape the opportunities and threats that companies face? If so, how? How worried are executives and other stakeholders about the impact of sustainability efforts on the corporate bottom line? What, if anything, are companies doing now to capitalize on sustainability driven changes? And what strategies are they pursuing to position themselves competitively for the future?

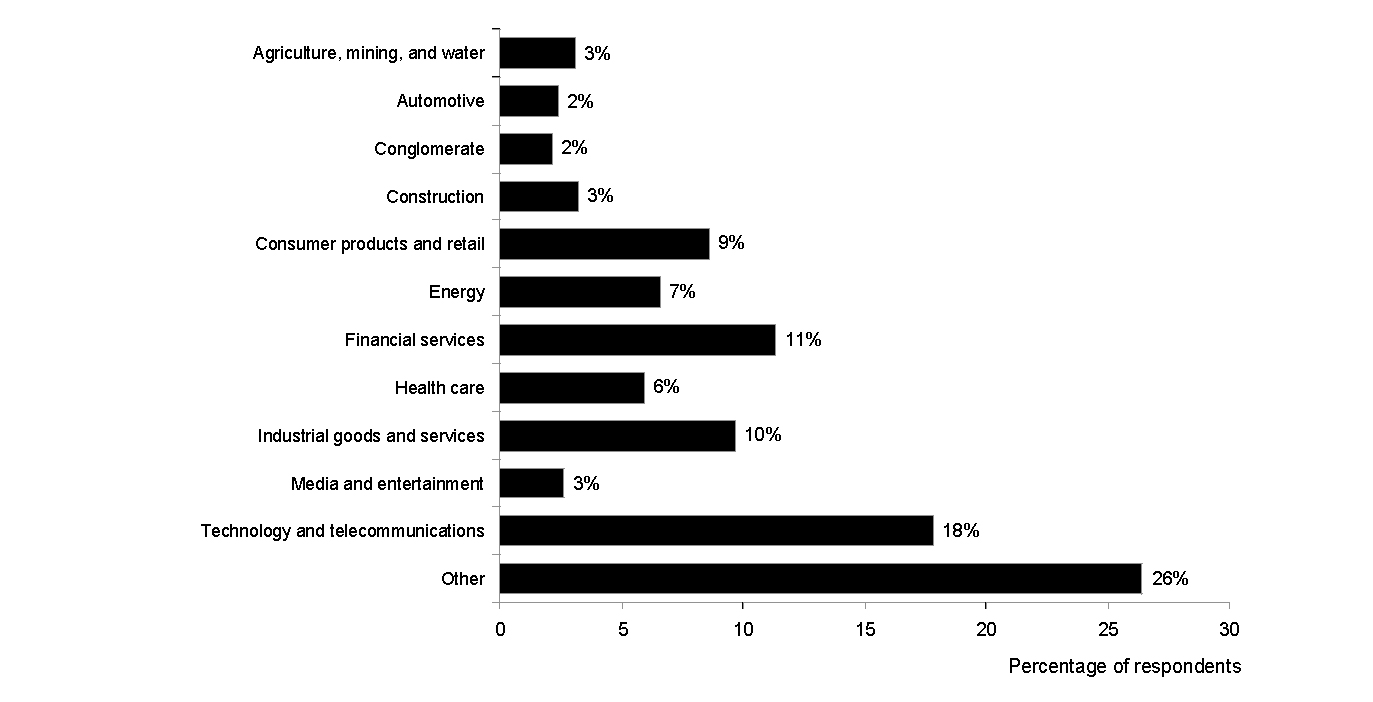

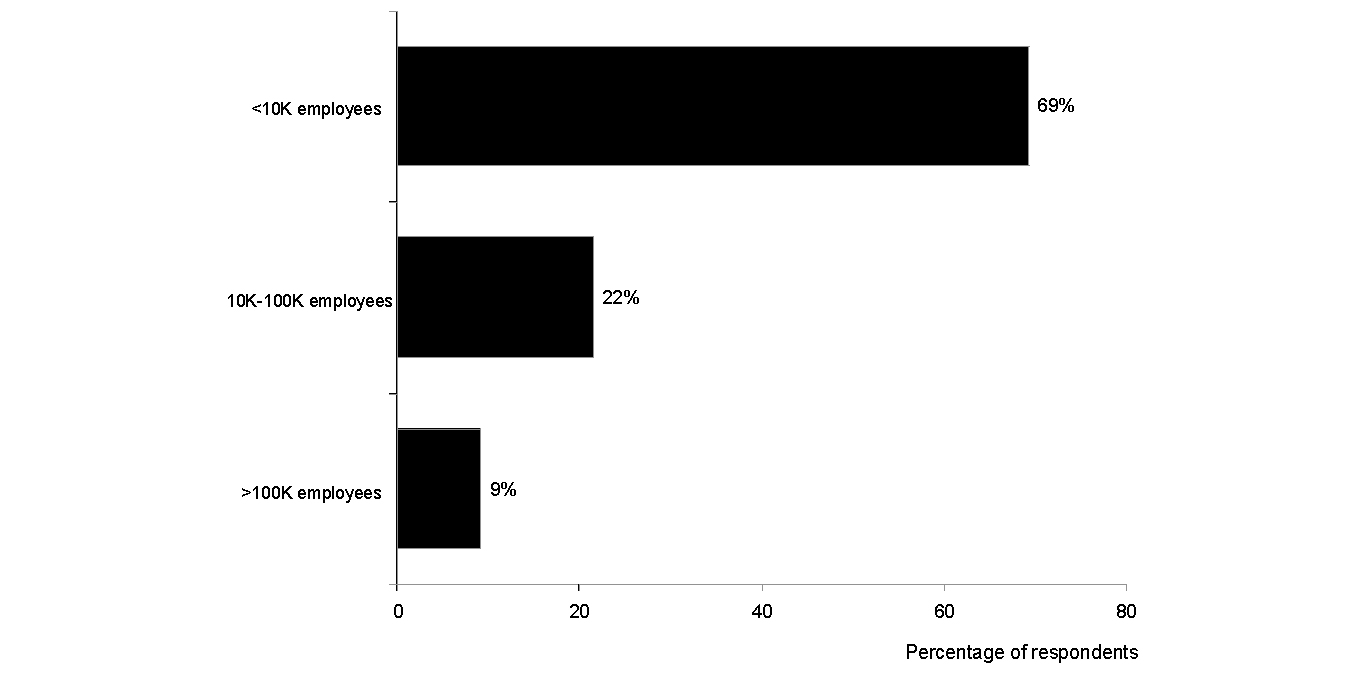

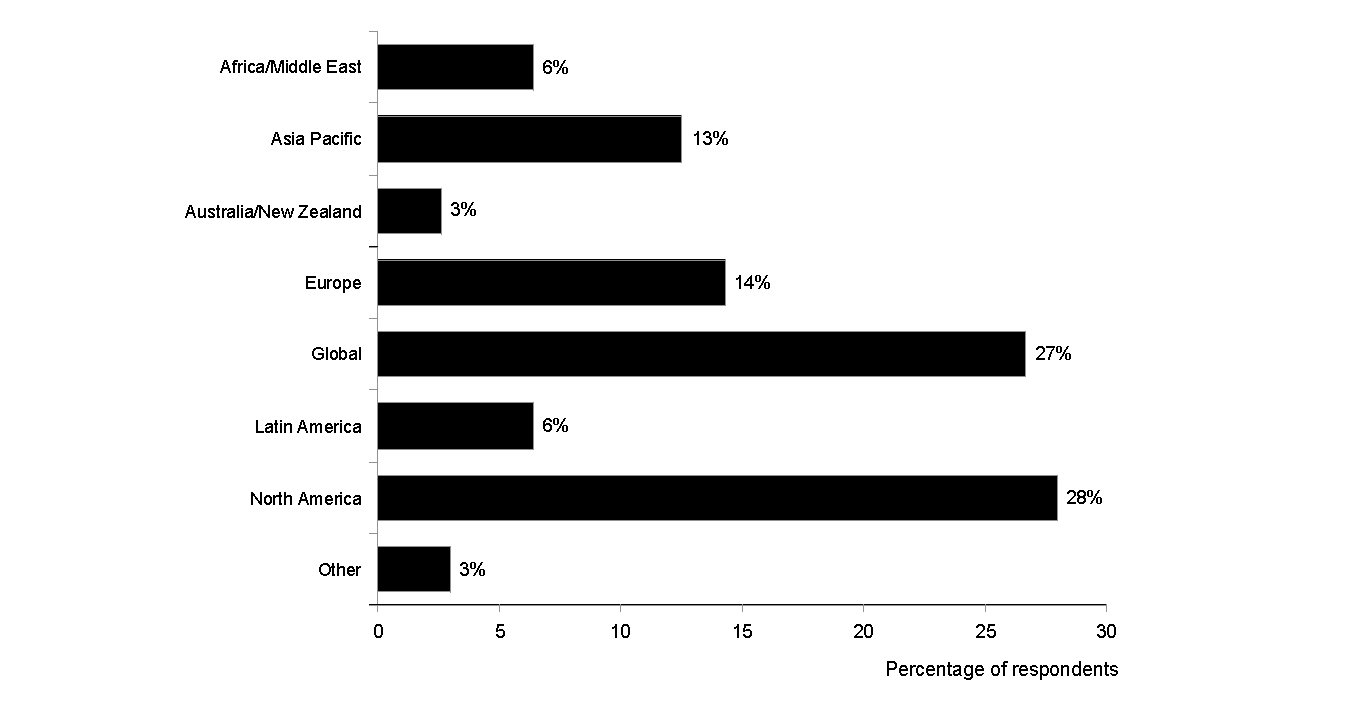

To begin answering those questions, the MIT Sloan Management Review and knowledge partner The Boston Consulting Group, with sponsorship support from business analytics provider SAS, are collaborating on a project called the Sustainability Initiative. As part of that effort, we recently launched a global survey of more than 1,500 corporate executives and managers about their perspectives on the intersection of sustainability and business strategy. (We plan to make this an annual survey.) Prior to the survey, to form hypotheses and shape its questions, we conducted more than 50 in-depth interviews with a broad mix of global thought leaders. Our interviewees included executives whose companies are at the cutting edge of sustainability (including General Electric, Unilever, Nike, Royal Dutch Shell, and BP) and experts from a range of disciplines such as energy science, civil engineering, and management. The insights of these two groups yielded a fascinating glimpse of sustainability’s current position on the corporate agenda — and where the topic may be headed in the future.

This report presents high-level findings from those surveys and interviews and offers interpretation and analysis of the results, along with a diagnostic tool. We hope that it provides executives food for thought as they consider how they can take their sustainability efforts to the next level.

For more about this work in sustainability, including exclusive in-depth interviews and additional feature articles, please see the online exploration at MIT Sloan Management Review’s Sustainability Initiative website.

Executive Summary

There is a strong consensus that sustainability is having — and will continue to have — a material impact on how companies think and act.

- More than 92 percent of survey respondents said that their company was addressing sustainability in some way.

- There was also a strong consensus that the underlying drivers of sustainability are highly complex, interrelated, and secular, and that the corporate sector will play a key role in solving the long-term global issues related to sustainability.

Sustainability is surviving the downturn.

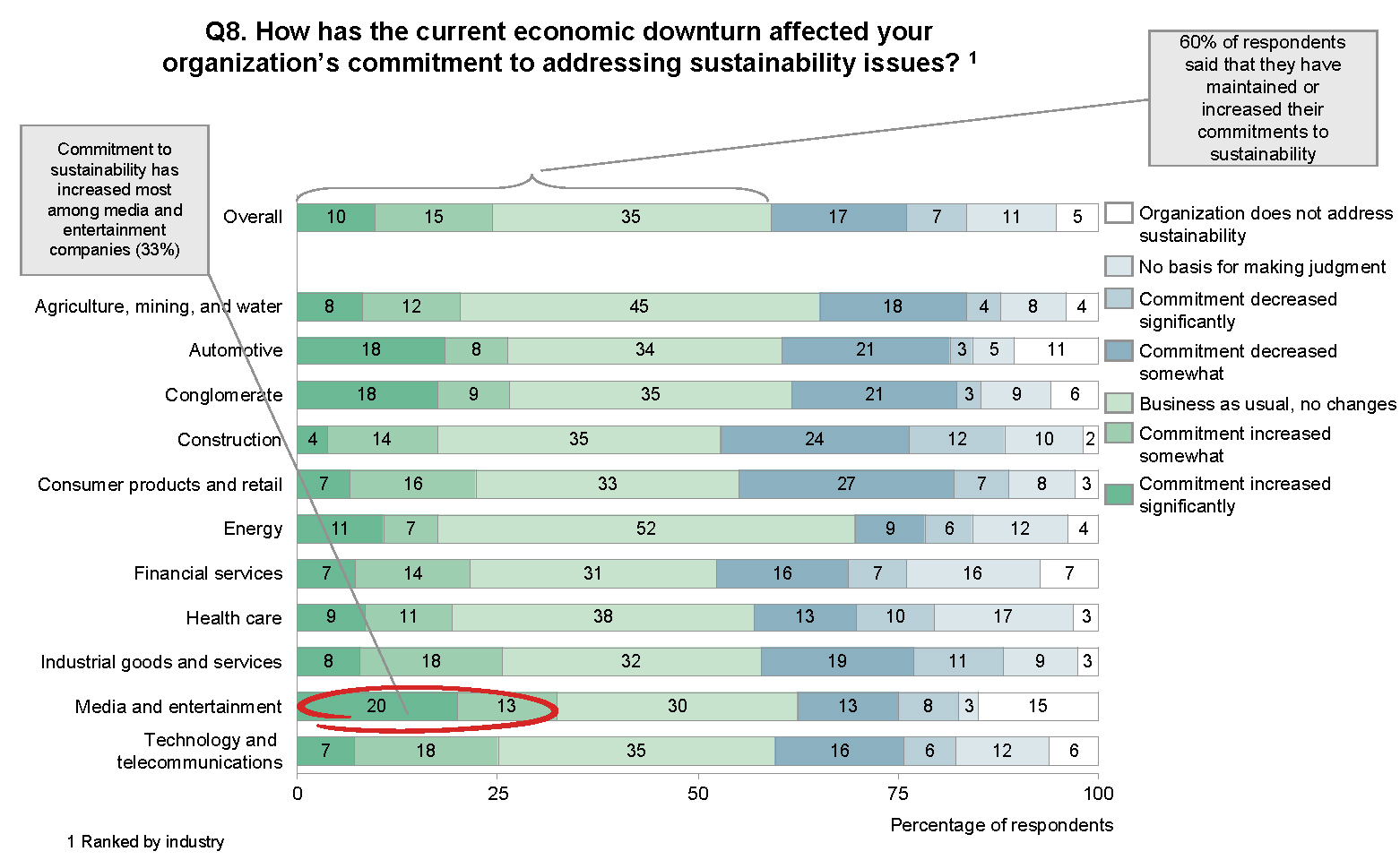

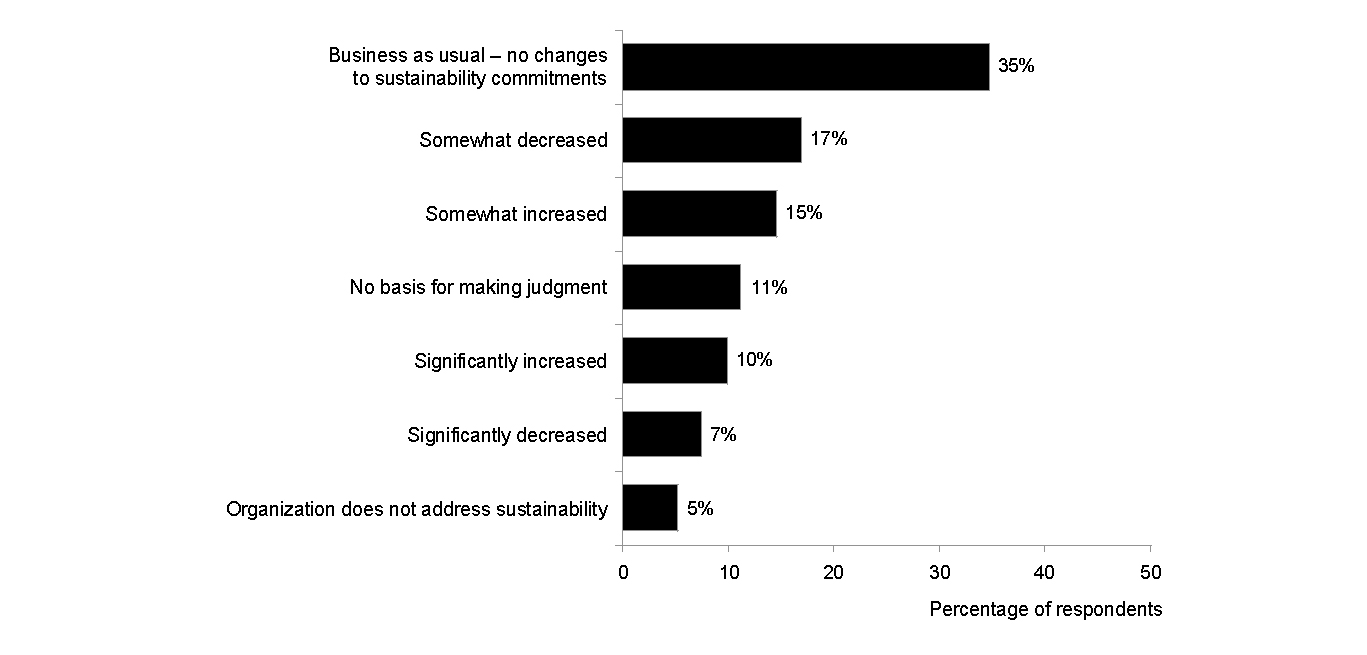

- Fewer than 25 percent of survey respondents said that their company had decreased its commitment to sustainability during the downturn.

- Respondents in some segments, such as the automotive industry and the media and entertainment industry, have reported an increased company commitment to sustainability, on average.

Although almost all the executives in the survey thought that sustainability would have an impact on their business and were trying to address this topic, the majority also said that their companies were not acting decisively to exploit the opportunities fully and mitigate the risks that sustainability presents.

- The majority of sustainability actions undertaken to date appear to be limited to those necessary to meet regulatory requirements.

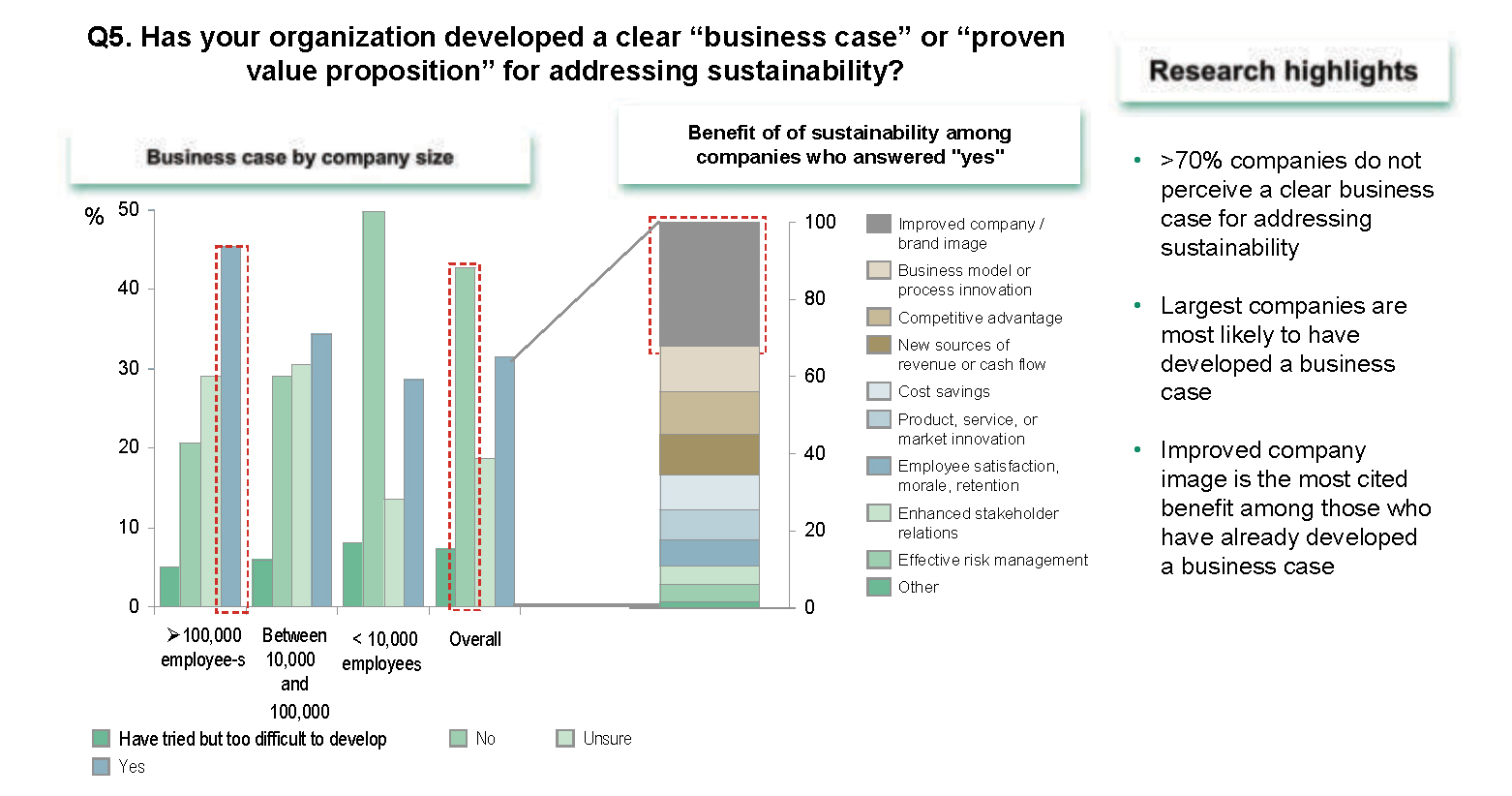

- More than 70 percent of survey respondents said that their company has not developed a clear business case for sustainability.

A small number of companies, however, are acting aggressively on sustainability — and reaping substantial rewards.

- Once companies begin to act aggressively, they tend to unearth more opportunity, not less, than they expected to find, including tangible bottom-line impacts and new sources of competitive advantage.

- The early movers’ approaches have several key characteristics in common, offering some helpful ideas on how to proceed.

Thought leaders and executives with experience in sustainability interpreted sustainability concerns (and their management implications) far more broadly than did executives lacking such experience. This understanding can open sometimes surprising opportunities for capturing advantage.

- While sustainability’s so-called novice practitioners thought of the topic mostly in environmental and regulatory terms, with any benefits stemming chiefly from brand or image enhancement, practitioners with more knowledge about sustainability expanded the definition for sustainability well outside the “green” silo. They tended to consider the economic, social, and even personal impacts of sustainability-related changes in the business landscape. Simply put, they saw sustainability as an integral part of value creation.

- Self-identified experts in sustainability believed more strongly in the importance of engaging with suppliers across the value chain. Sixty-two percent of these respondents considered it necessary to hold suppliers to specific sustainability criteria; only 25 percent of novices felt the same. There was a high correlation between the depth of a business leader’s experience with sustainability and the drivers and benefits that he or she perceives. For example, 68 percent of business leaders with sustainability expertise indicated the financial logic for their organization’s investments in sustainability initiatives was either “advantage — material financial returns” or “attractive — incremental financial returns.” This suggests that the more people know about sustainability, the more thoughtfully they evaluate it and the more opportunity they see in it — and the more they think it matters to how companies manage themselves and compete.

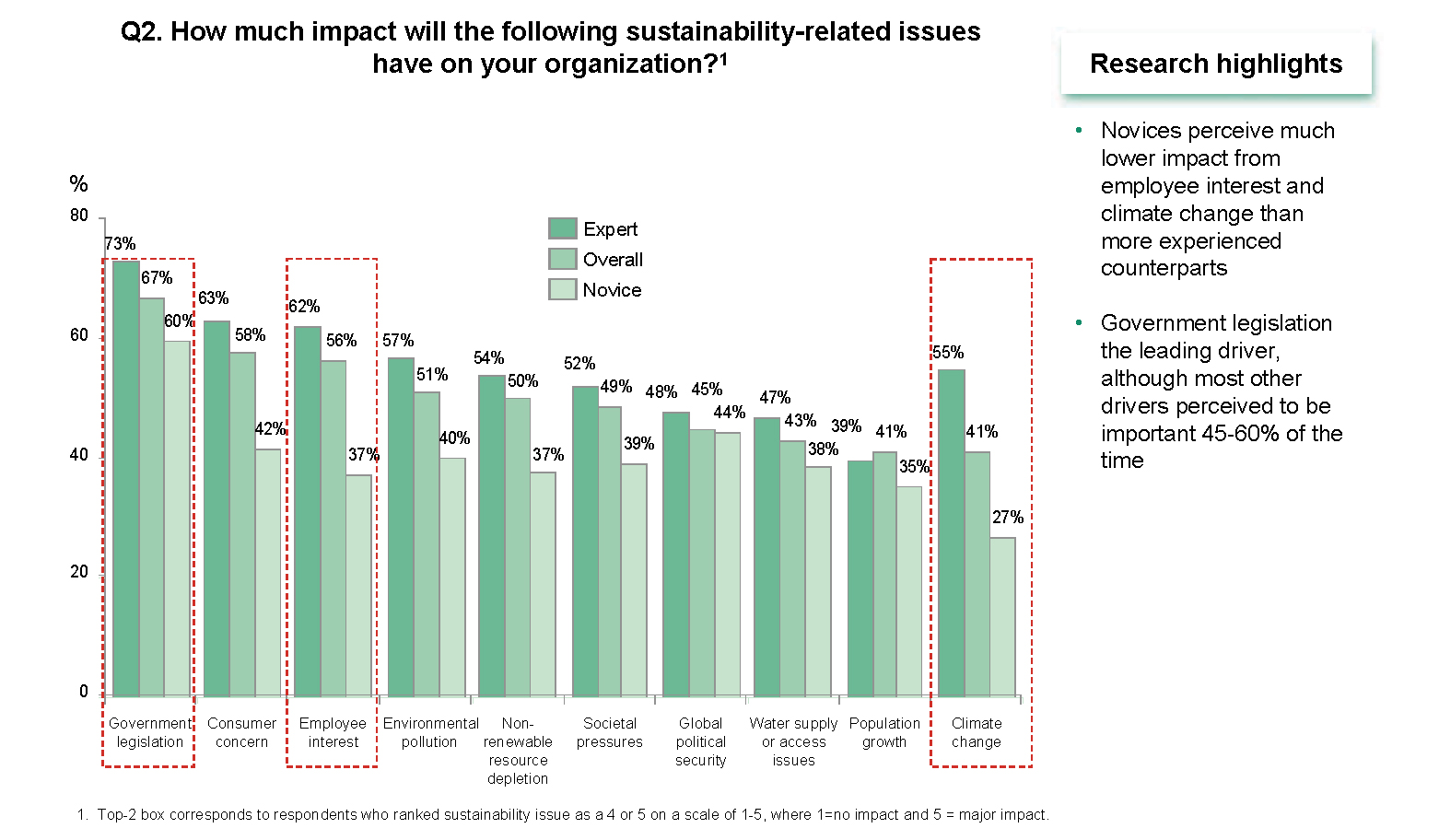

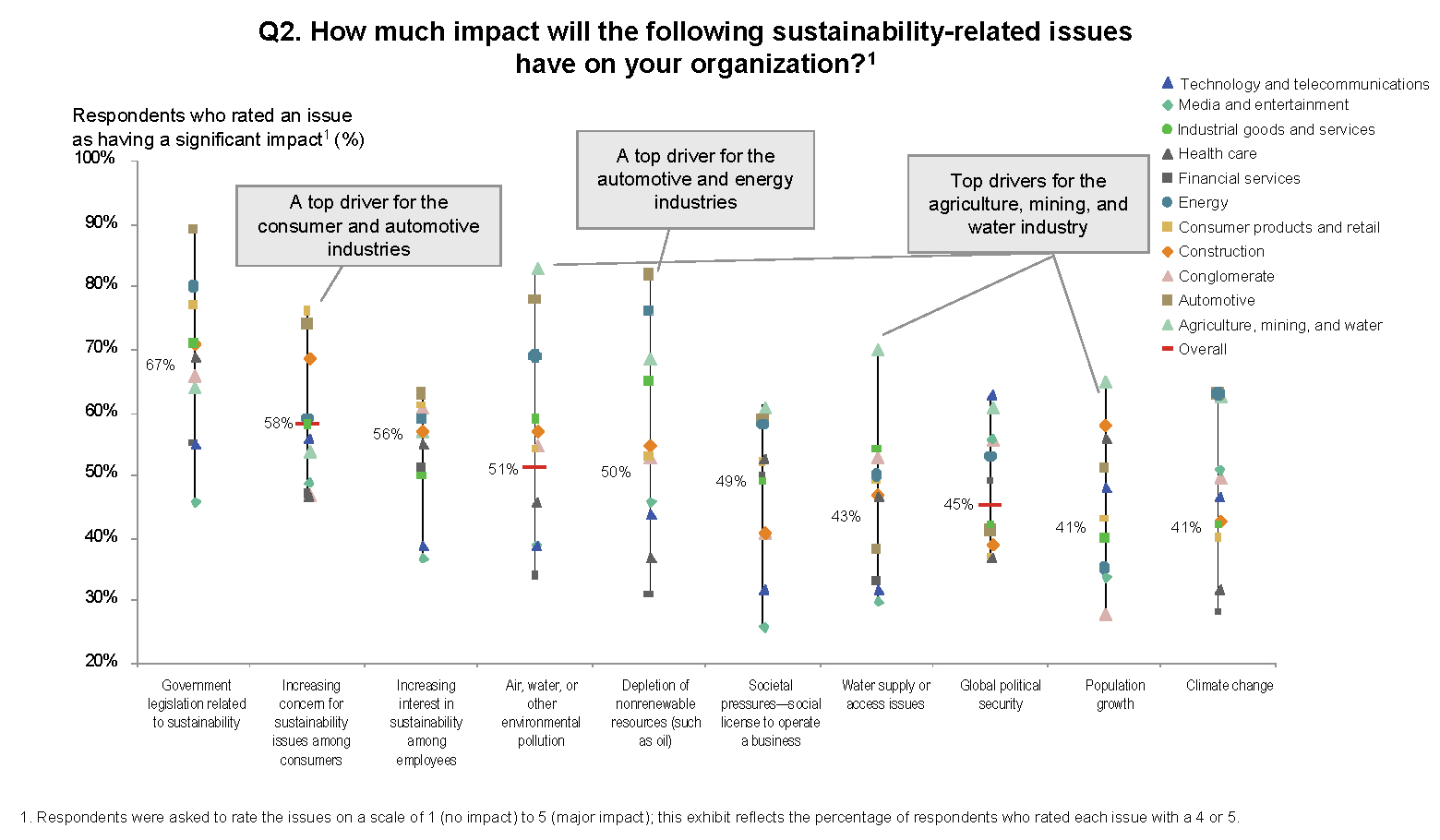

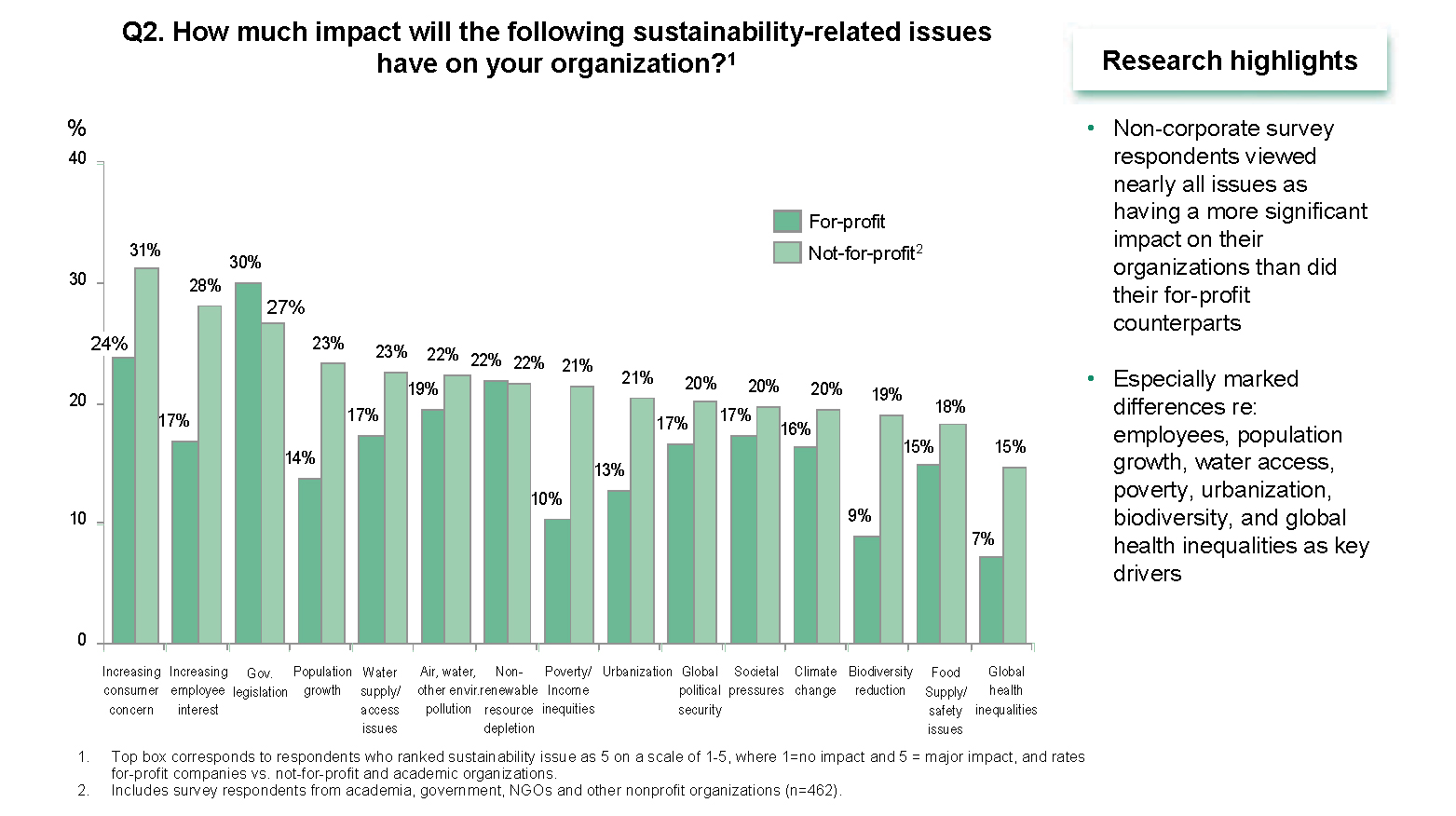

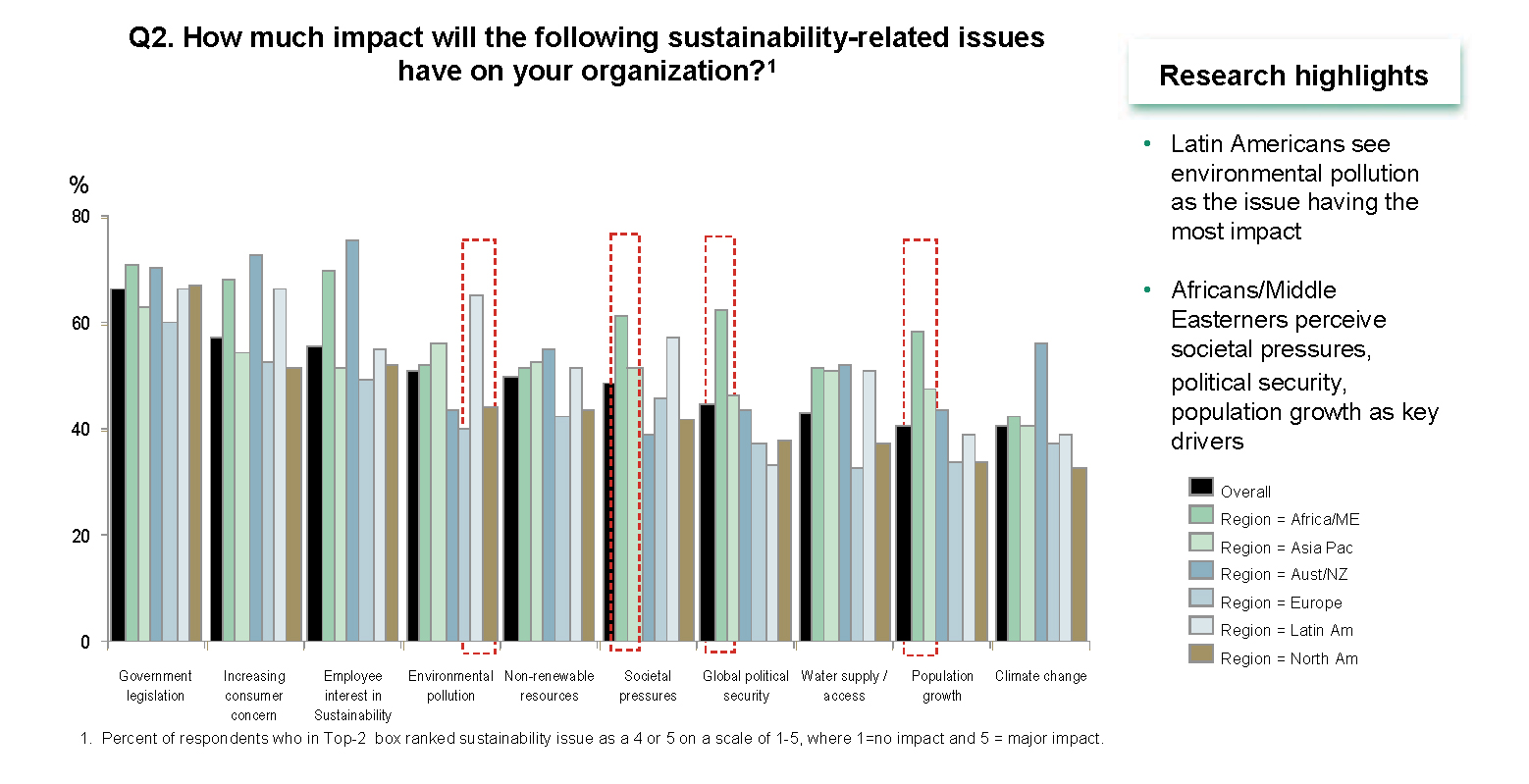

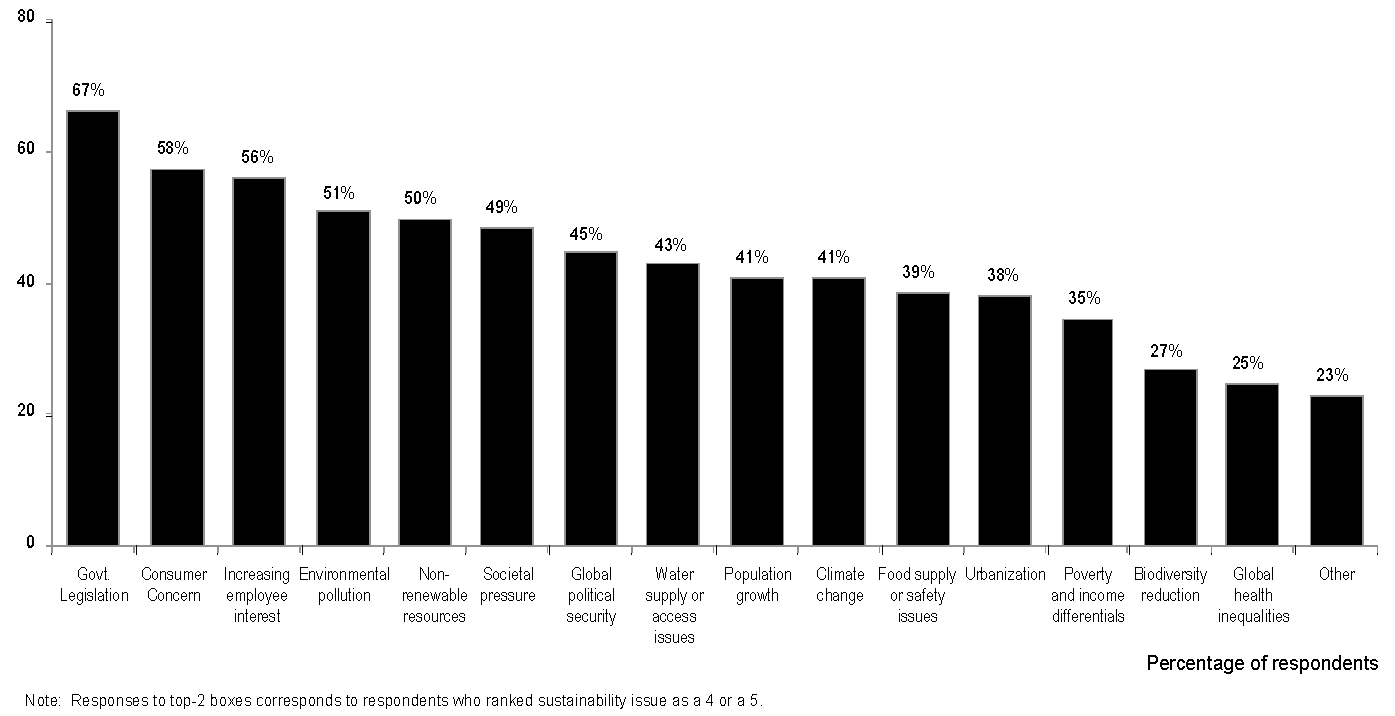

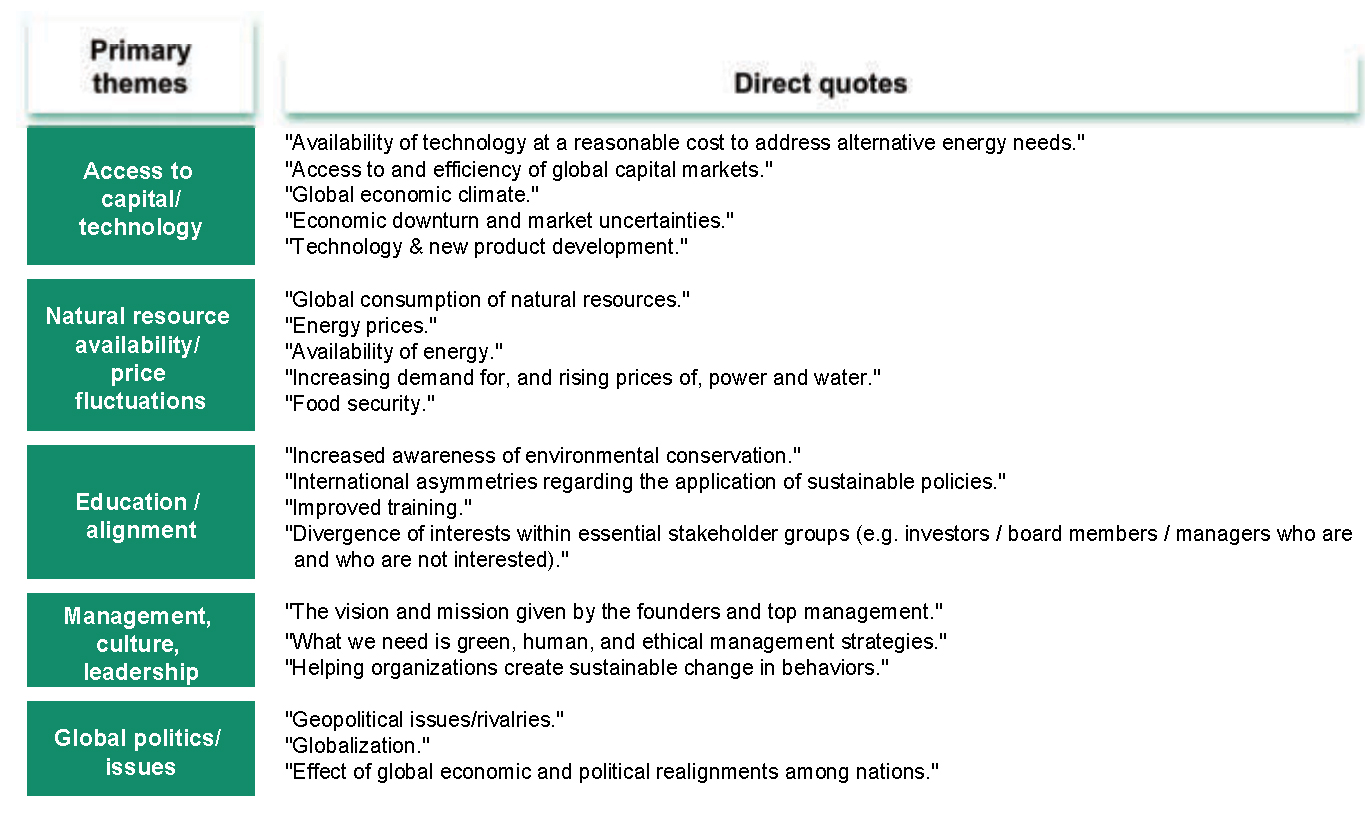

According to survey respondents, the biggest drivers of corporate sustainability investments — that is, the forces that are having the greatest impact on companies — are government legislation, consumer concerns, and employee interest in sustainability.

- Government legislation was cited as the principal driver by nearly all the industries we analyzed — with the exceptions of agriculture, mining, and water companies, which cited environmental pollution as the issue having the greatest impact on their companies, and companies in both the media and entertainment industry and the technology and telecommunications industry, which identified global political security as having the greatest impact.

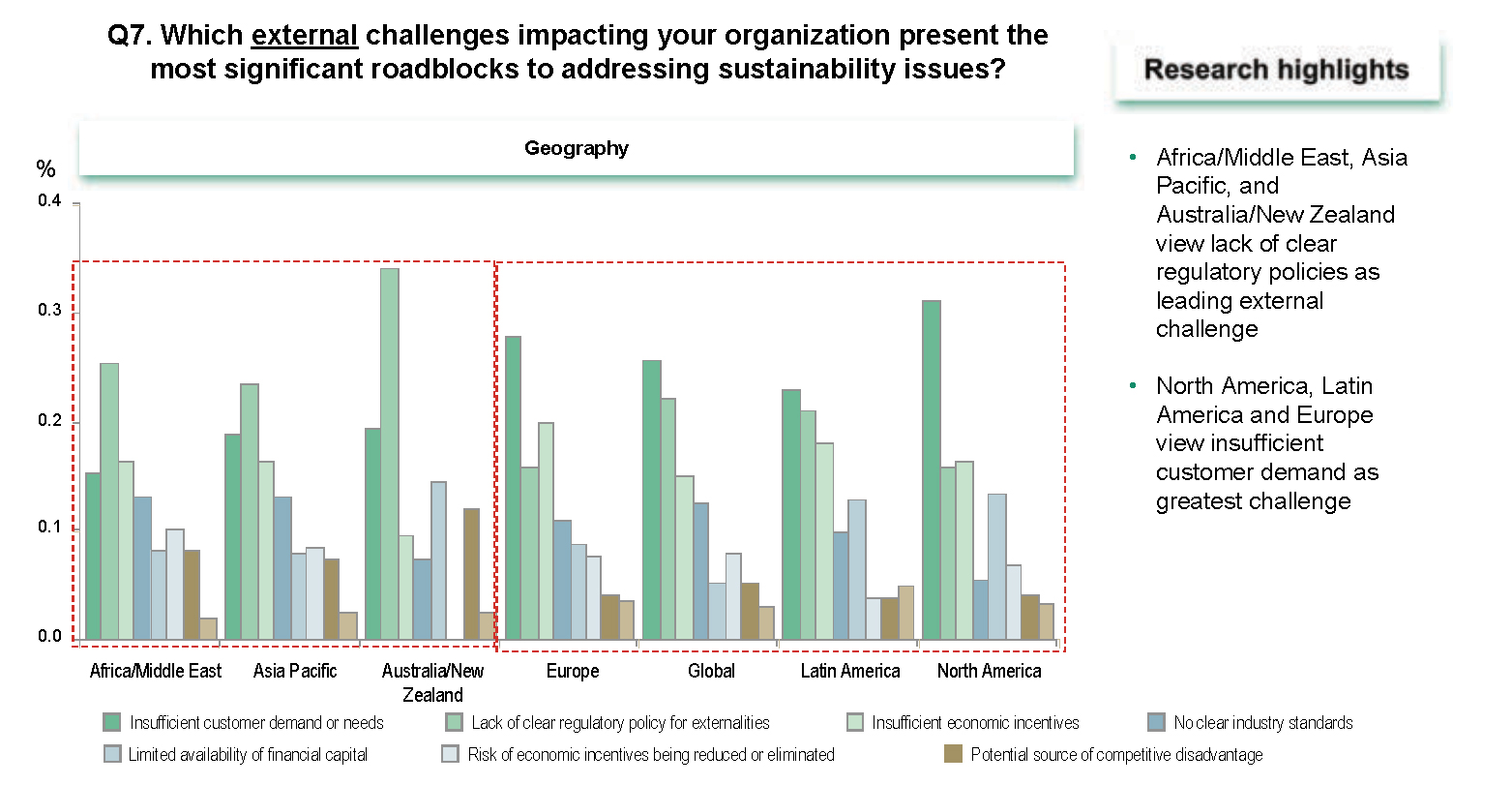

- Consumer concerns were viewed as a relatively more critical force in sustainability among companies based outside of the United States and Europe.

Sustainability will become increasingly important to business strategy and management over time, and the risks of failing to act decisively are growing.

- Our research indicates that companies need to develop a better understanding of the implications of sustainability for their business — and that the companies already doing so are being rewarded.

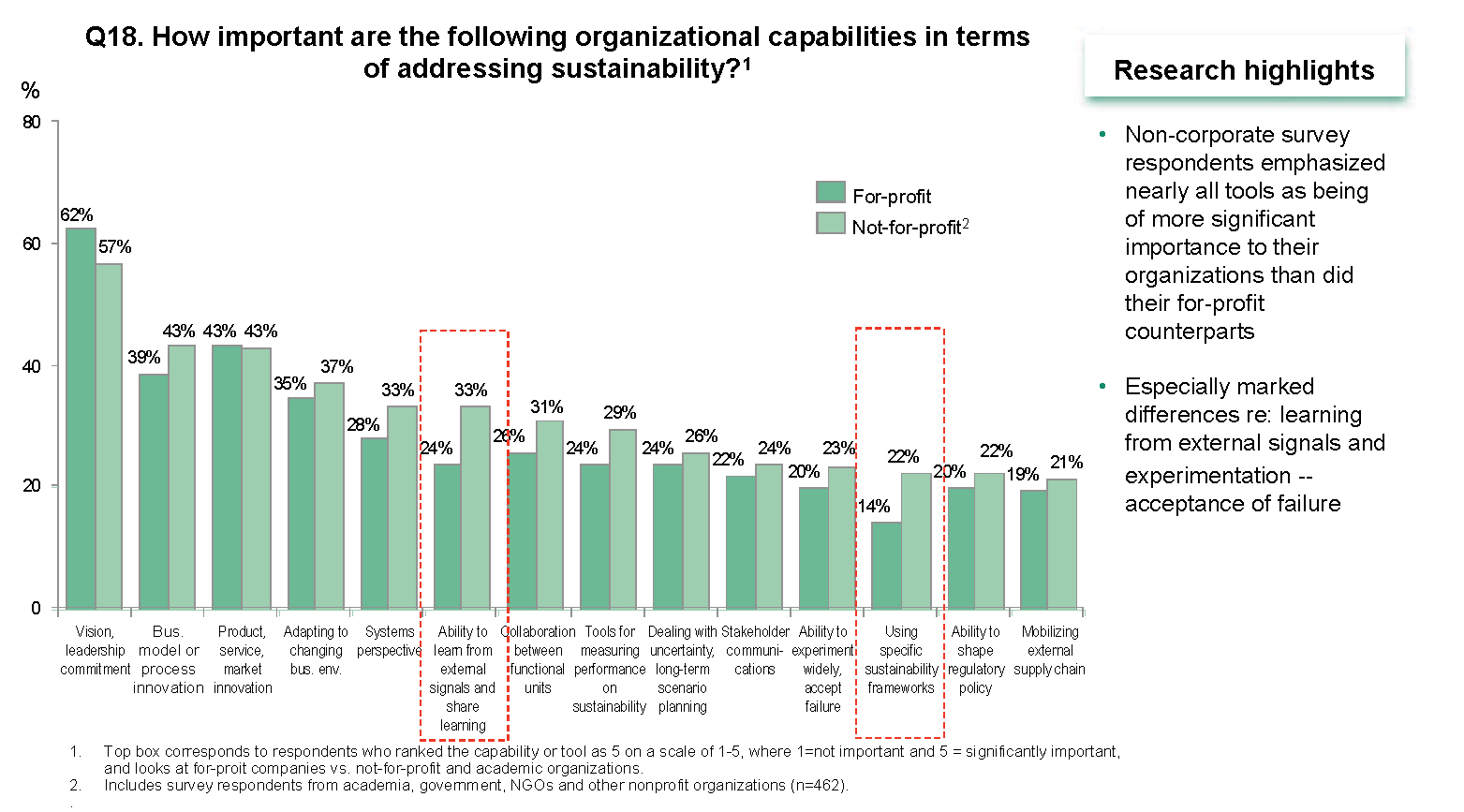

- Companies will need to develop new capabilities and characteristics, including the ability to operate on a systemwide basis and collaborate across internal and external boundaries; a culture that rewards and encourages long-term thinking; capabilities in the areas of activity measurement, process redesign, and financial modeling and reporting; and skills in engaging and communicating with external stakeholders.

Survey and Interview Findings

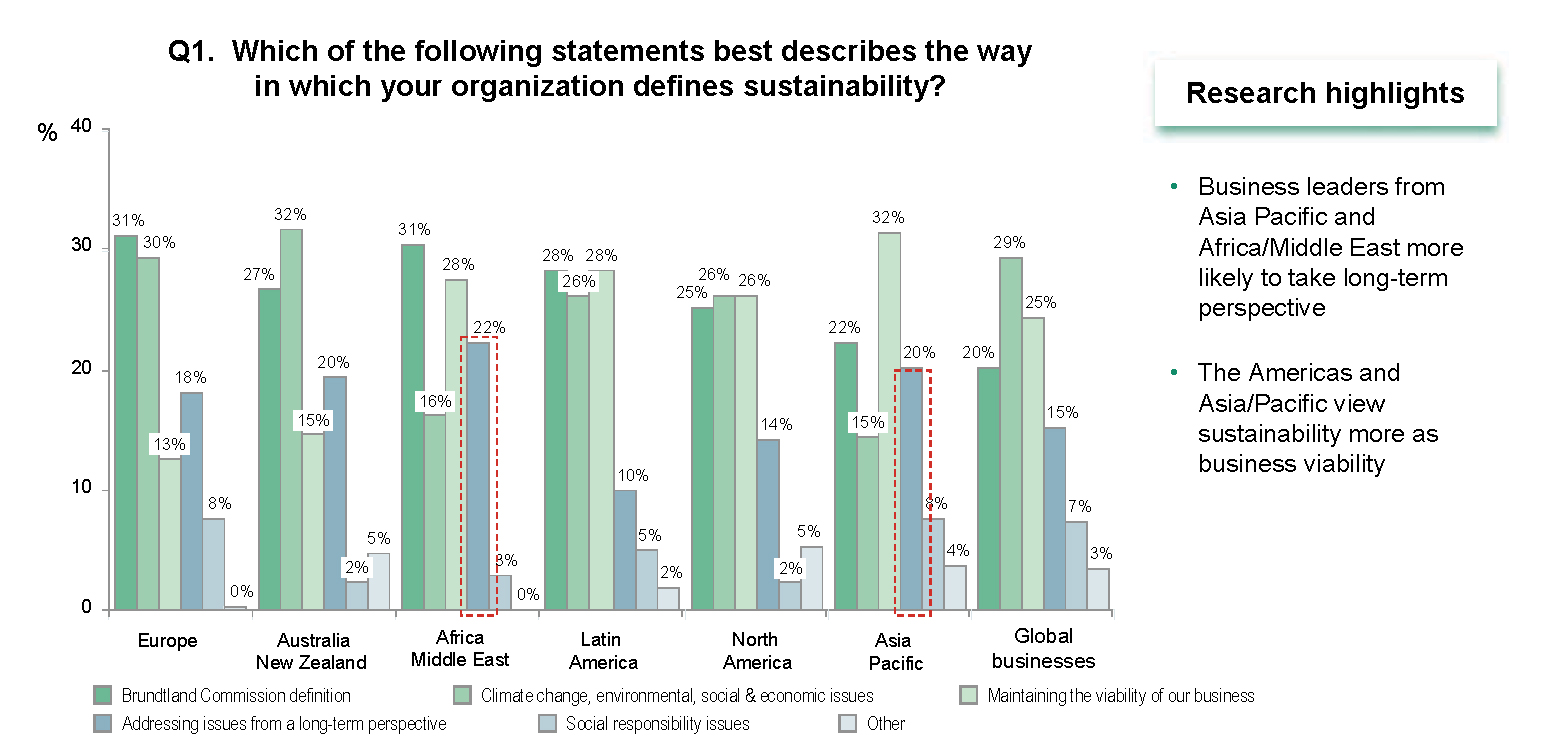

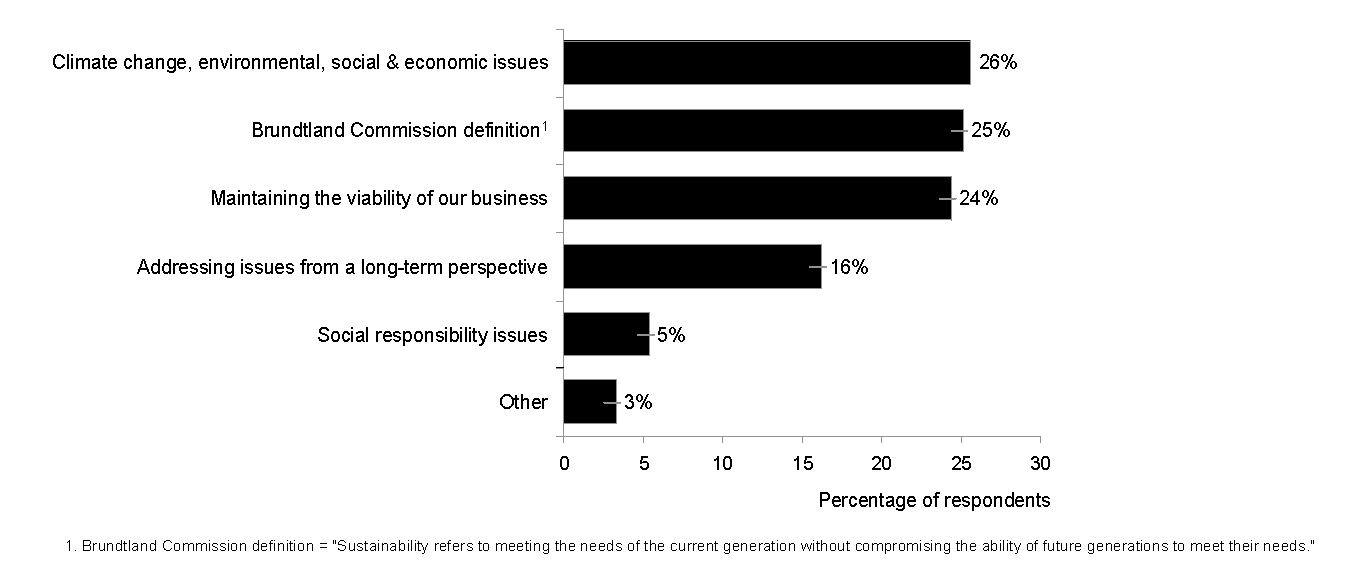

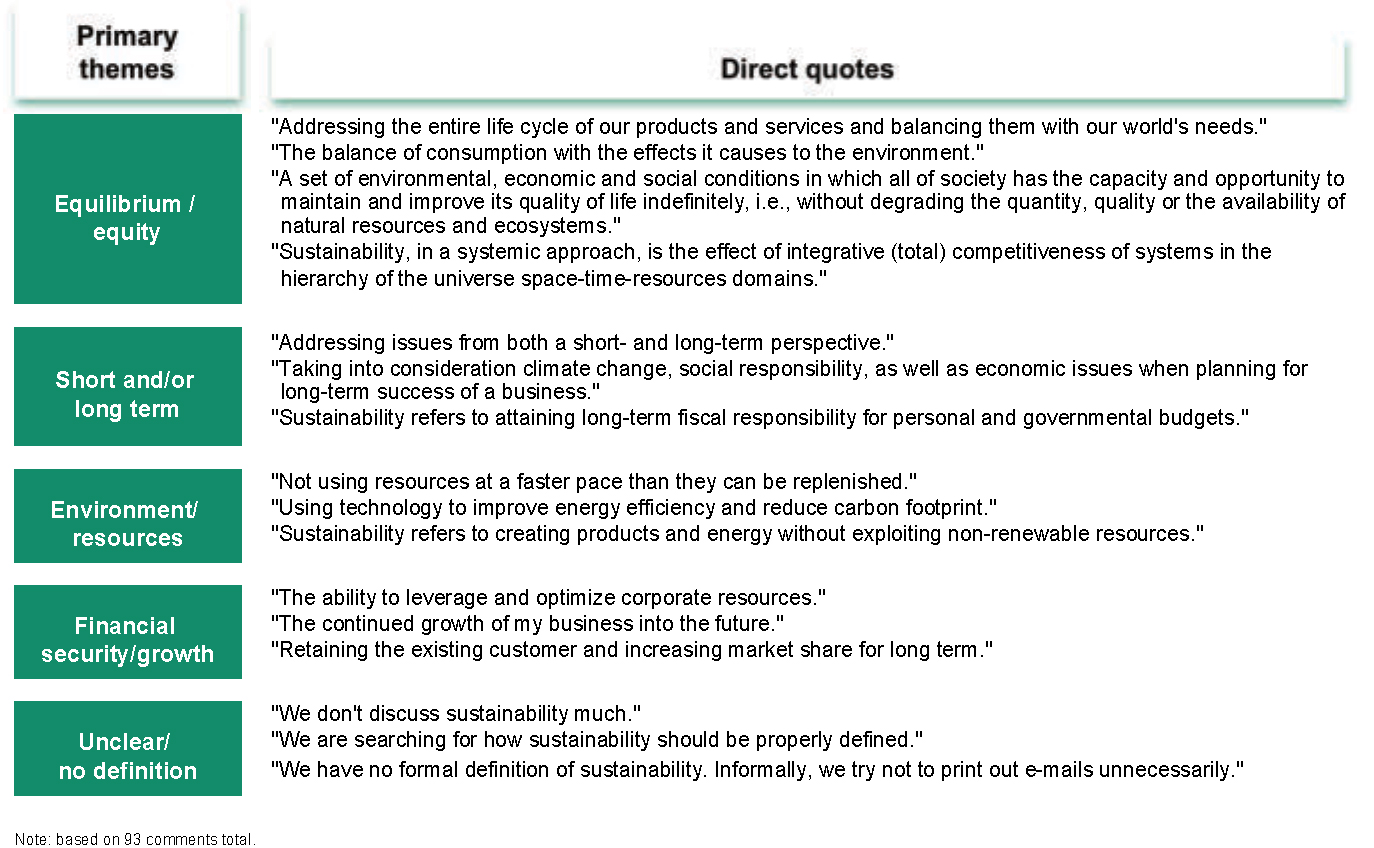

First and foremost, our survey revealed that there is no single established definition for sustainability. Companies define it in myriad ways — some focusing solely on environmental impact, others incorporating the numerous economic, societal, and personal implications. Yet while companies may differ in how they define sustainability, our research indicates that they are virtually united in the view that sustainability, however defined, is and will be a major force to be reckoned with — and one that will have a determining impact on the way their businesses think, act, manage, and compete.1

“I think that the world has reached a tipping point now. We’re beyond the debates over whether [addressing sustainability] is something that needs to be done or not — it’s now mostly about how do we do it. And from an ecomagination perspective, it’s not about altruism, it’s about creating value.”Steve Fludder, vice president, ecomagination, GE

The Consensus: Sustainability Matters

Indeed, the overwhelming majority of the corporate respondents in the broader survey group — as well as nearly all the corporate executives interviewed in the smaller thought leader group — told us that sustainability-related issues were having or will soon have a material impact on their business. For example, 92 percent of the survey respondents told us that their company was already addressing sustainability in some way. Furthermore, there was a strong consensus that the underlying drivers of sustainability are highly complex, interrelated, and secular, and that the corporate sector will play a key role in solving the long-term global issues related to sustainability.

Sustainability Is Not a “Topic du Jour”

A good indication that sustainability is here to stay is the fact that fewer than one-fourth of the survey respondents told us that their companies have pulled back on their commitment to sustainability during the downturn. (See Exhibit 1.) Respondents in some segments, such as the automotive industry or the media and entertainment industry, have reported an increased company commitment to sustainability, relative to the average.

“In the last year or two, everything has changed. People are starting to suspect that these are really strategic issues that will shape the future of our businesses. The specifics are different depending on industry and context, but we’re in the beginning of a historic wake-up.”

Peter Senge, faculty member MIT Sloan School of Management, and founding chair, Society for Organizational Learning

A number of corporate executives in the thought leader group also shared their belief that the downturn has accelerated a shift toward a greater corporate focus on sustainability — particularly toward sustainability related actions that have an immediate impact on the bottom line. At the same time, several respondents in the broader survey group lamented having to meet higher-than-normal criteria for sustainability investments. They told us that it was increasingly difficult to maintain investments in the current financial environment because of limited access to capital.

Opinions Diverge on Some Aspects of Sustainability

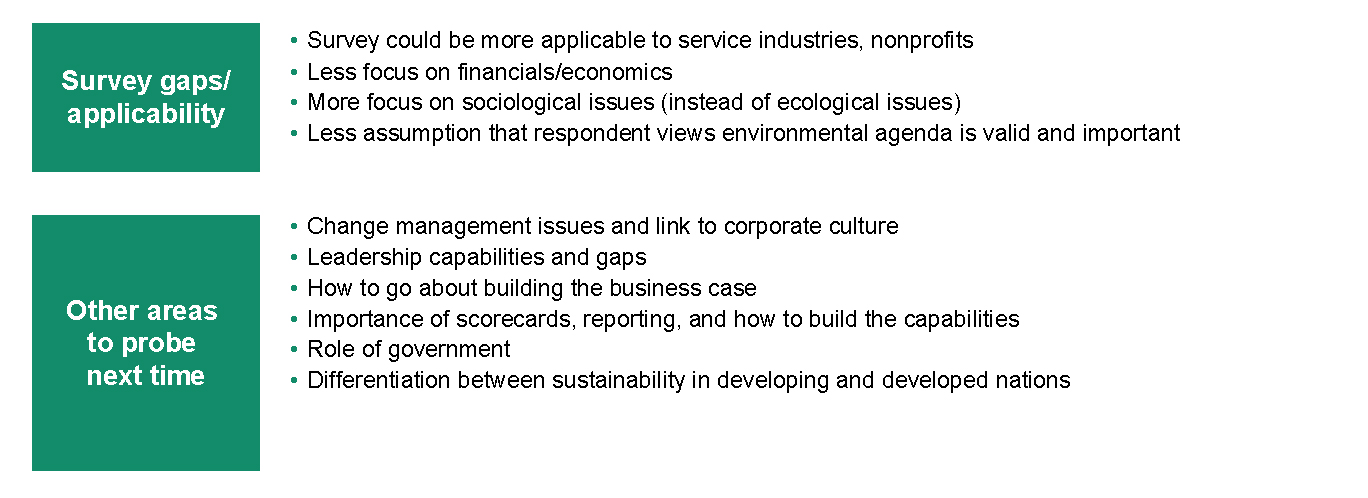

Although the points above reflect a strong convergence of views on the overarching question of sustainability’s impact on business, significant divergence in opinion arose regarding particular aspects of sustainability. We highlight some of the most noteworthy differences below.

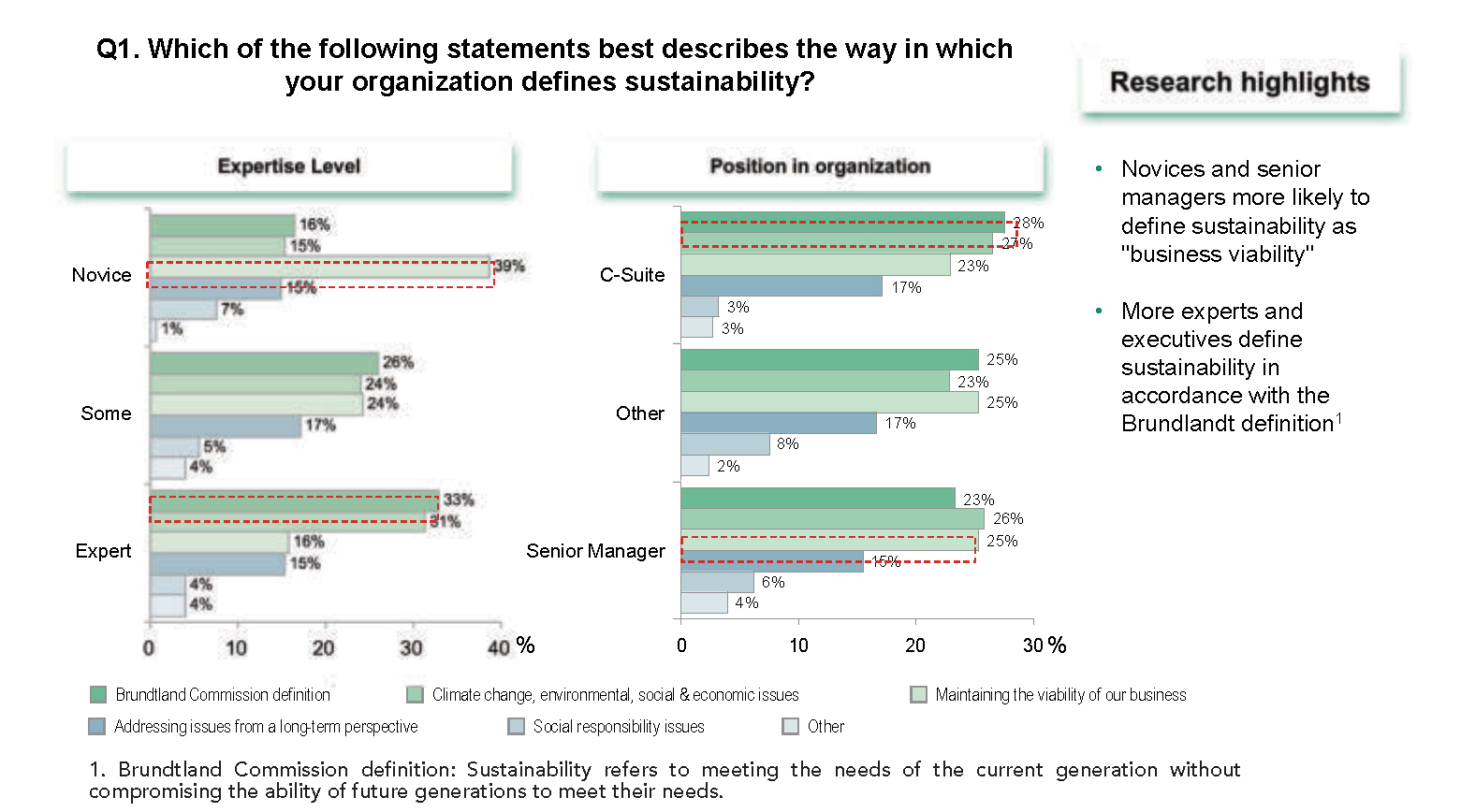

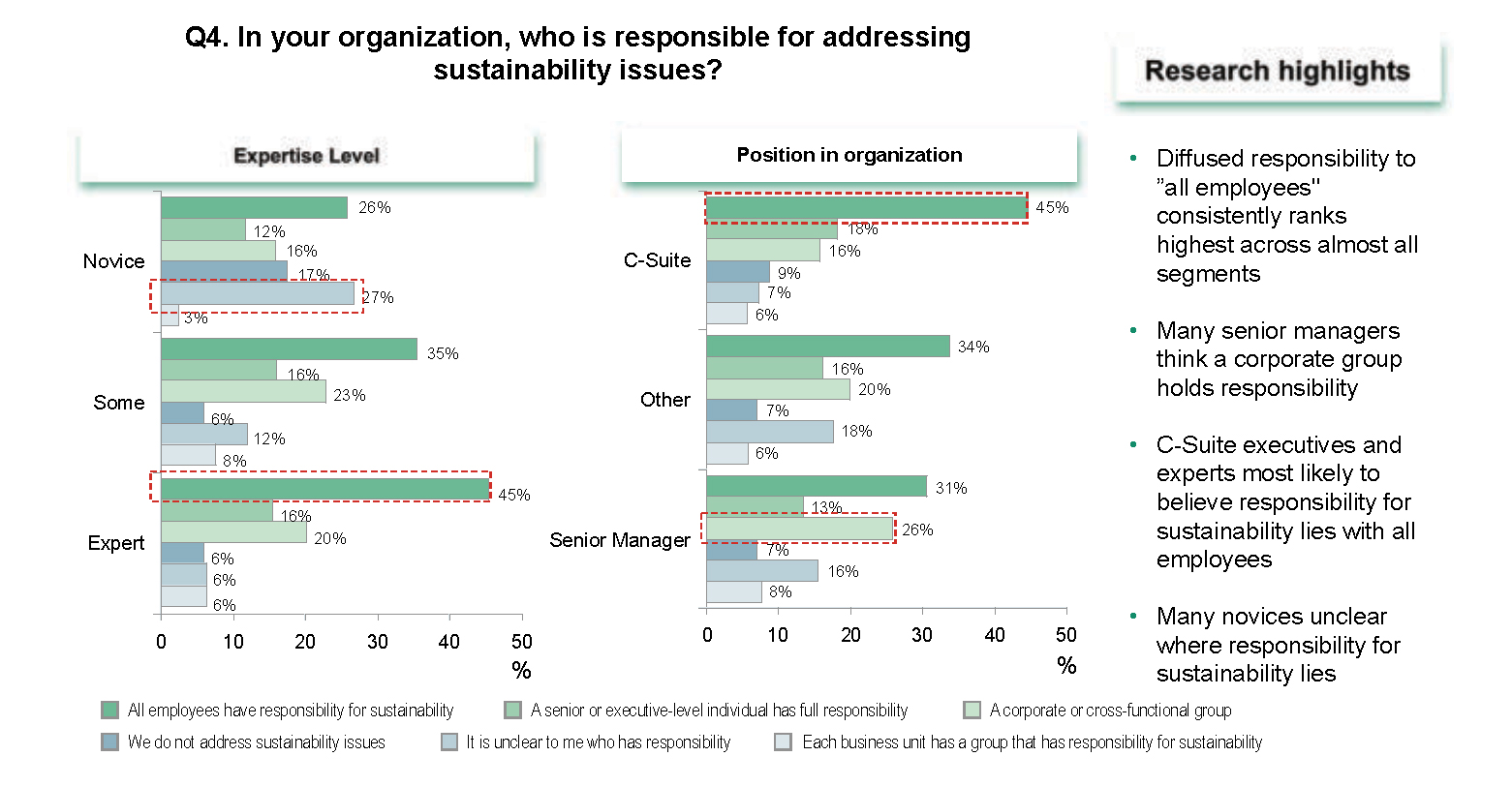

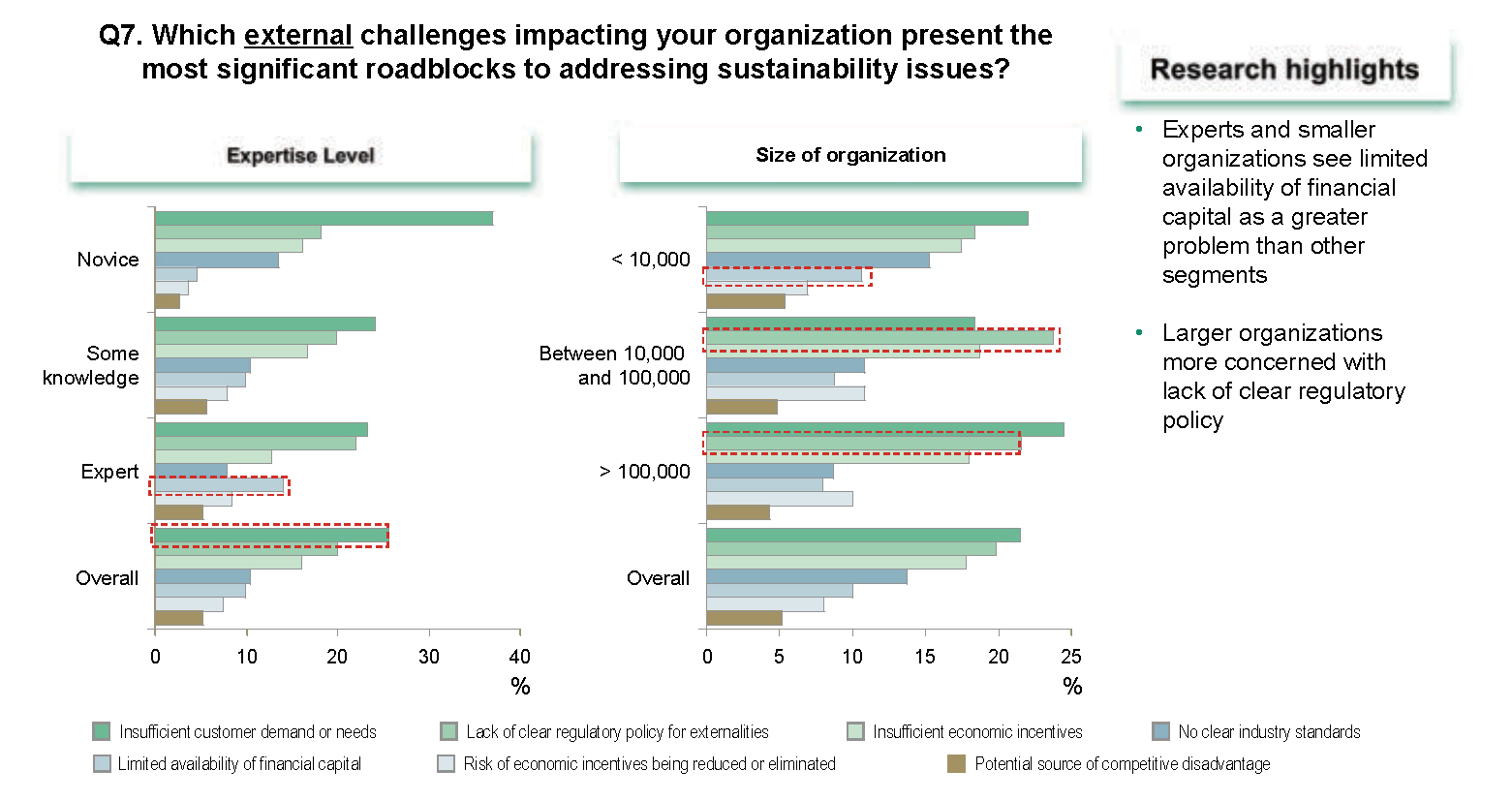

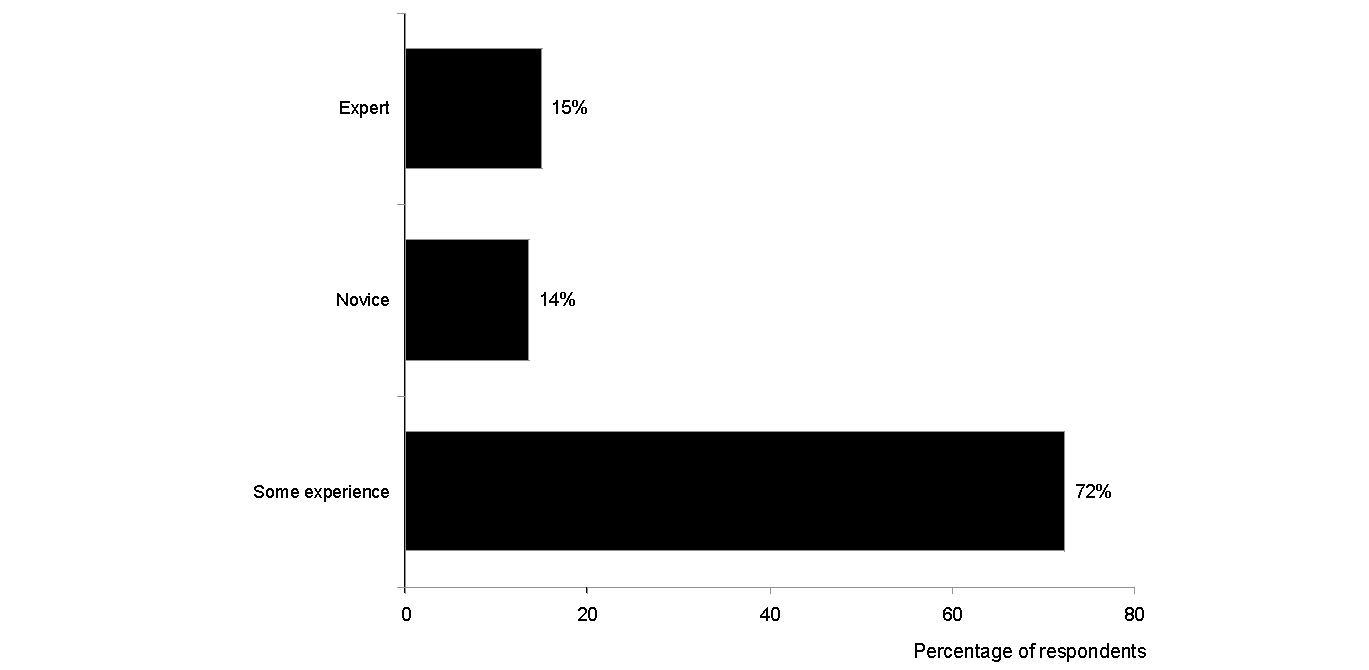

Self-identified sustainability experts viewed the topic differently than those who considered themselves novices in the area. We asked corporate respondents in the broader survey group to rate their experience with sustainability by classifying themselves as either a sustainability expert, an individual with some experience, or a novice. In a number of cases, the perspectives held by these three groups were at odds.

“The issue we have this year is how do you continue to make progress without the capital that you’ve had in the past?”

William O’Rourke, vice president of sustainability and environment, health, and safety, Alcoa

- Experts defined sustainability more comprehensively than novices did. While a significant proportion (40 percent) of novices defined sustainability simply as “maintaining business viability,” nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of experts used one of two widely accepted definitions: the so-called Brundtland Commission definition or the Triple Bottom Line definition, both of which incorporate economic, environmental, and social considerations.2

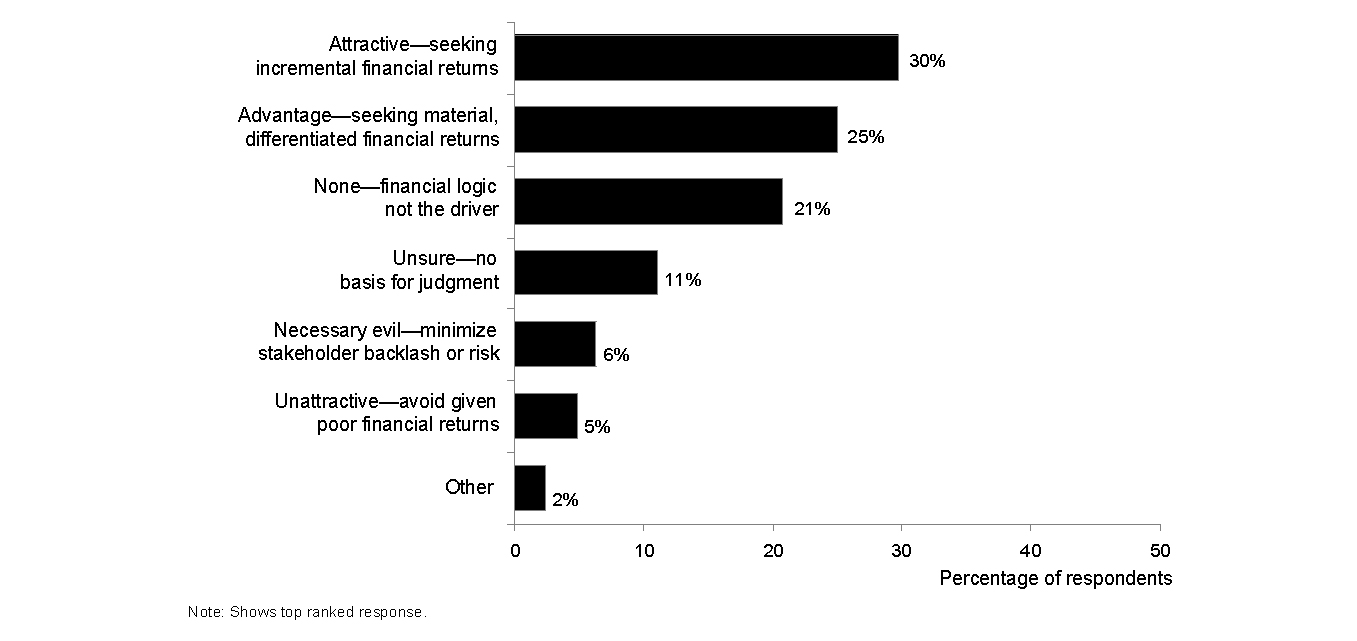

- Whereas 50 percent of the experts we surveyed said that their company had a compelling business case for sustainability, only 10 percent of the novices we surveyed did. Further, when asked about the logic underlying their organization’s investments (or lack thereof) in sustainability initiatives, 68 percent of experts cited improved financial returns compared with only 32 percent of novices.

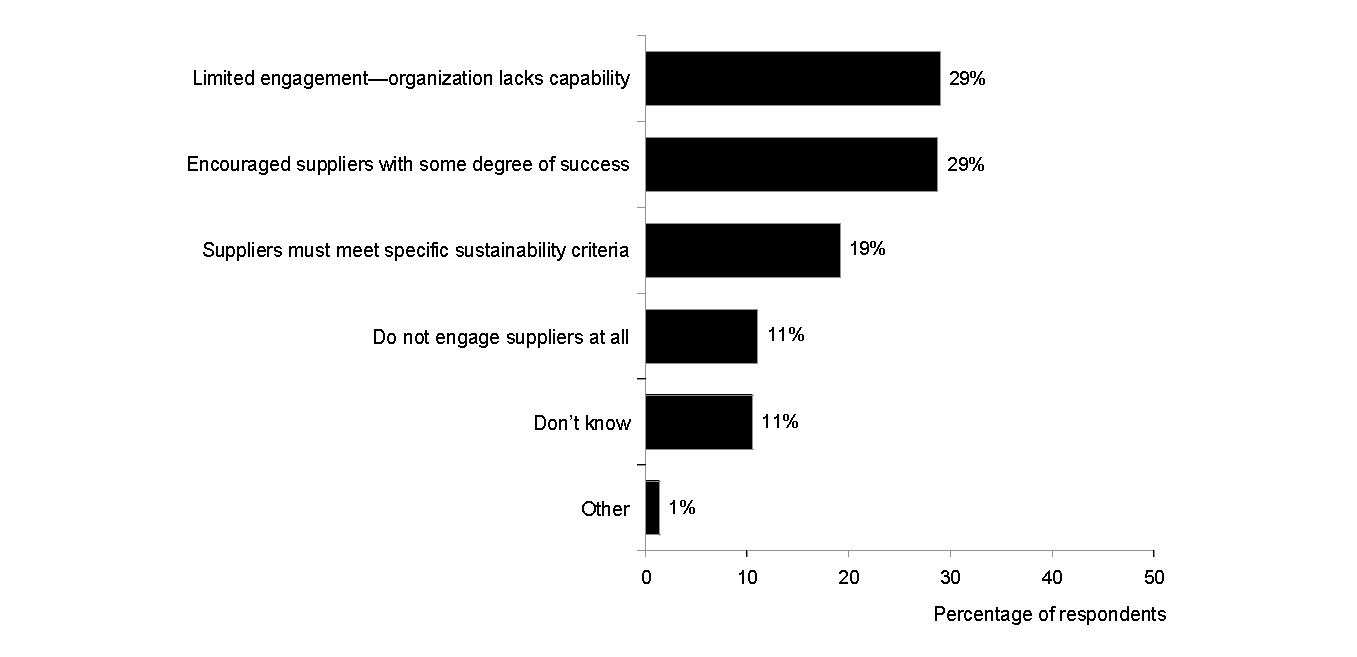

- Experts believed more strongly in the importance of engaging suppliers across the value chain. Sixty-two percent of the experts surveyed considered it necessary to hold suppliers to specific sustainability criteria; only 25 percent of surveyed novices felt the same.

It is noteworthy that surveyed experts’ views on the points above were largely consistent with those of the corporate executives in the thought leader group, with experience being the common denominator between the groups. Simply put, we conclude that the more people know about sustainability, the more thoughtfully they evaluate it and the more opportunity they see in it — and the more they think it matters to how companies position themselves and operate.

“All the benefits of sustainability are only possible if you tackle the issues on the supply chain. If not, it’s greenwashing.”

Dierk Peters, former international marketing manager, Unilever

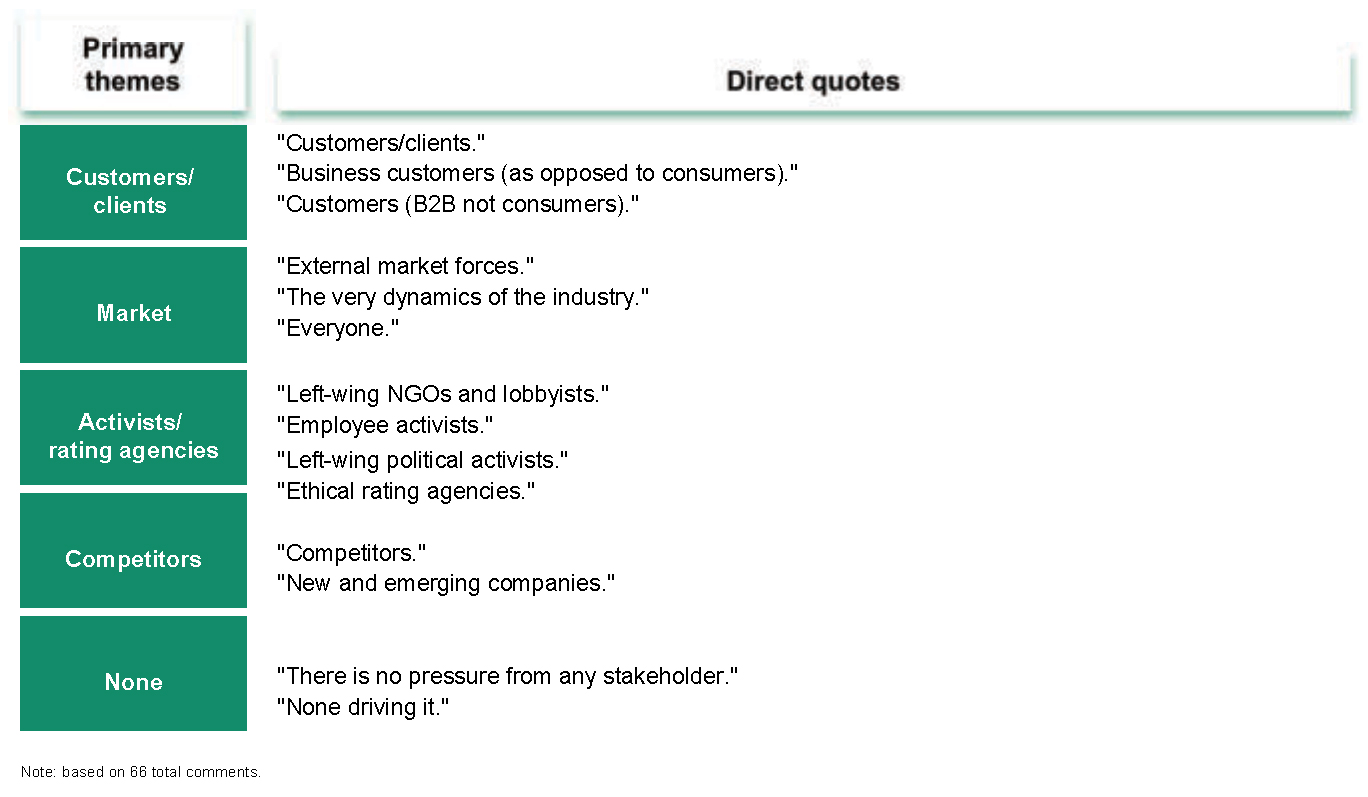

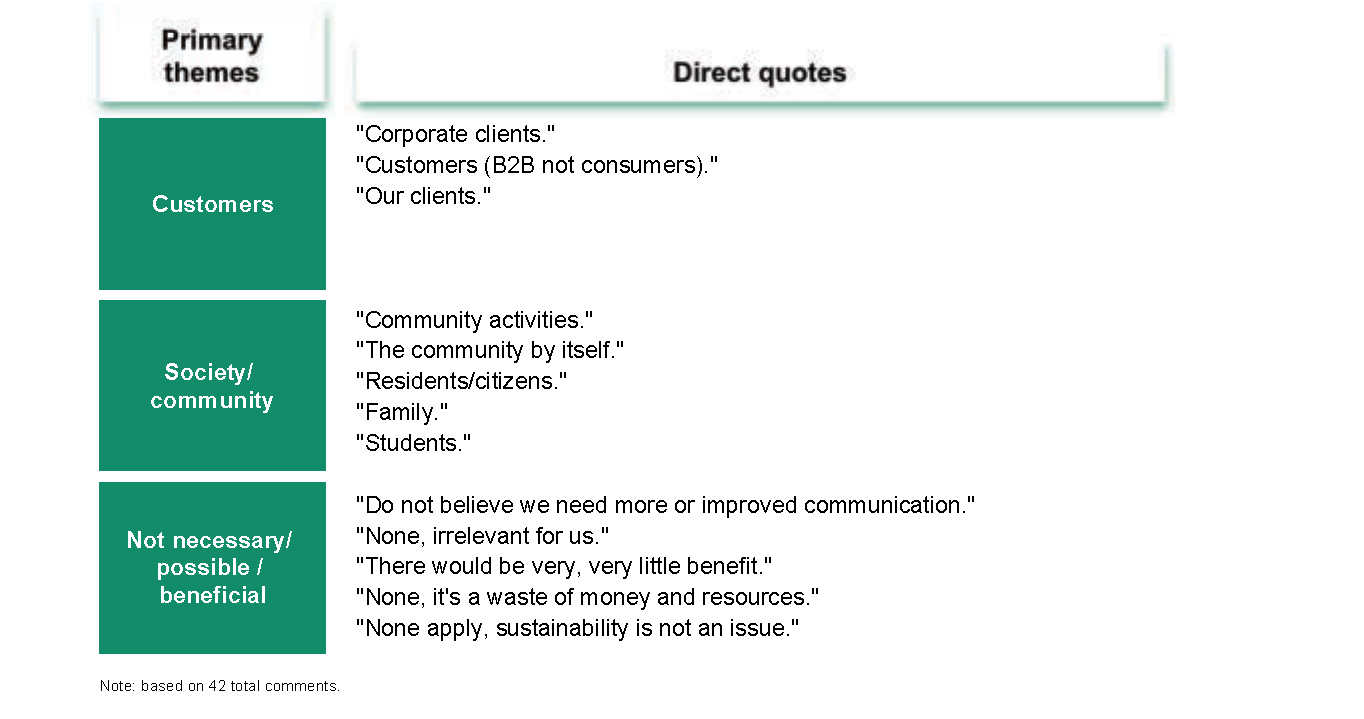

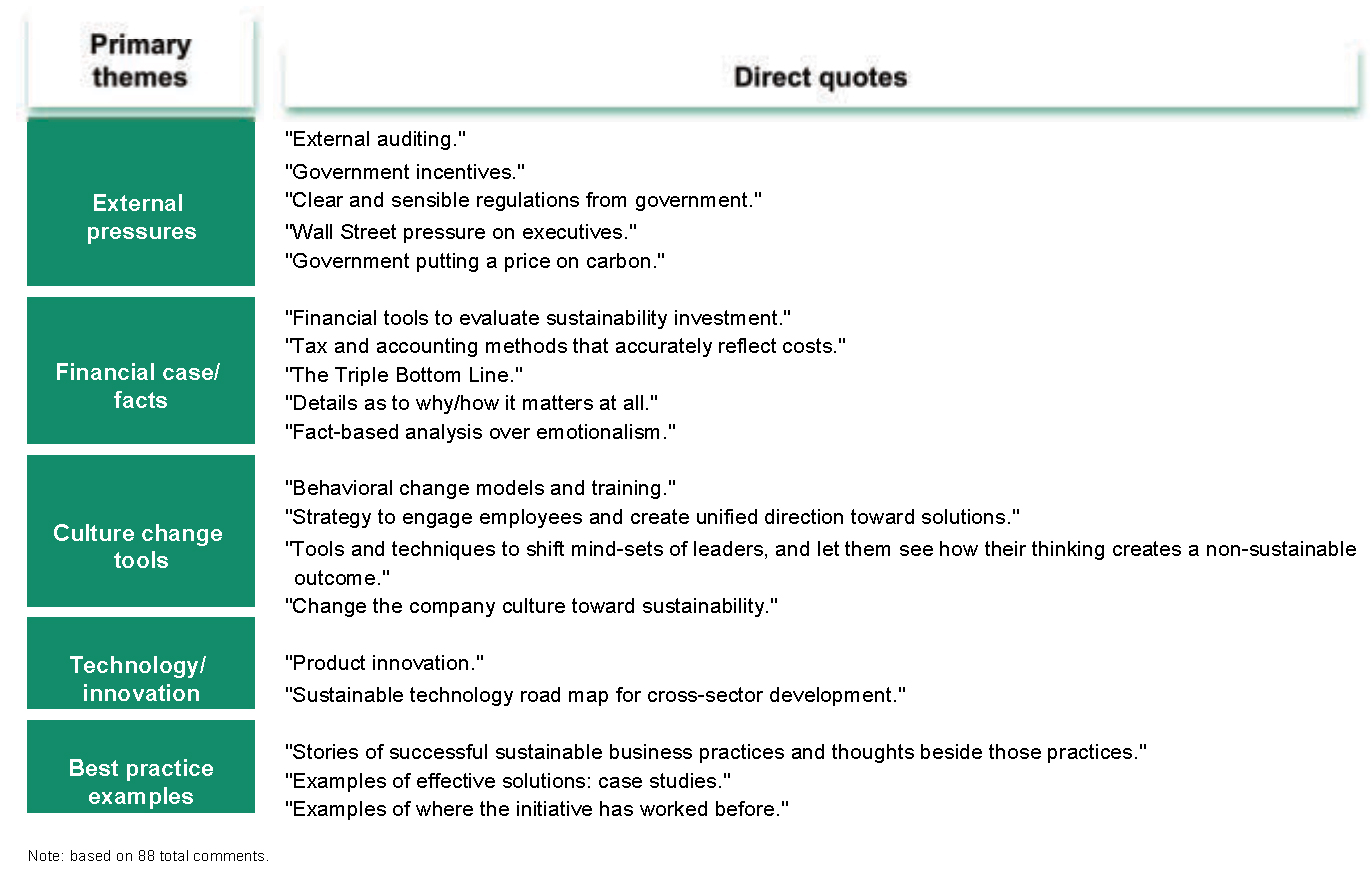

As an overall group, the corporate respondents in the broader survey group held different opinions from those of the thought leaders we interviewed. Perhaps because of their comparatively greater experience with sustainability, the thought leaders’ views on several aspects of sustainability diverged from those of the survey respondents — particularly with regard to the topic’s drivers and benefits. The major points of contention included the following:

“The essence of environmental strategy is to make it an issue for your competitor — not for your own company — … because you’ve already made sustainability an integral part of your business.”

Amory Lovins, chairman and chief scientist, Rocky Mountain Institute

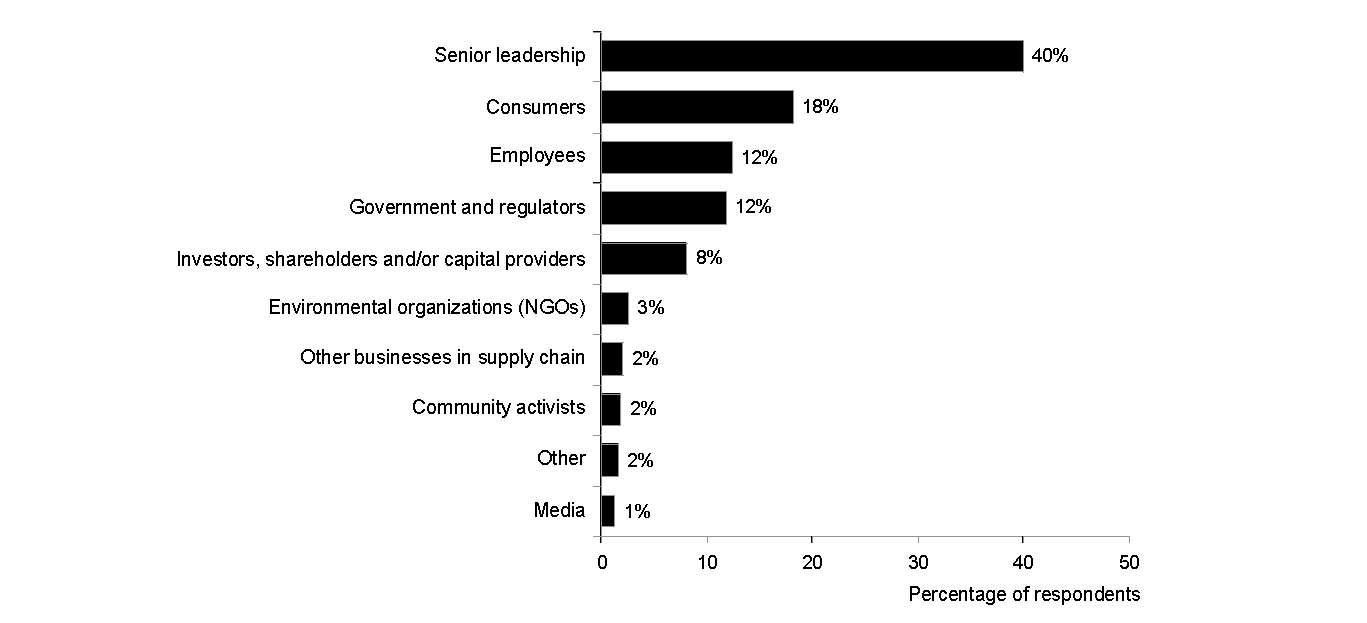

- Government Legislation. Overall, corporate respondents in the broader survey group deemed government legislation the sustainability-related issue with the greatest impact on their business. (See Exhibit 2.) Sixty-seven percent said that this issue had a significant impact on how their organization was approaching sustainability.3 By contrast, the thought leader group placed far less emphasis on government legislation as a driving force in sustainability. Further, many of the thought leaders we interviewed cited instances in which companies had played a role in shaping the regulatory framework rather than simply reacting to it. (For more about one company that actively shapes the regulatory environment and partners with government and other stakeholders, see the Mini-Case, “A Better Place: Charging Ahead in Favorable Regulatory Climates.”)

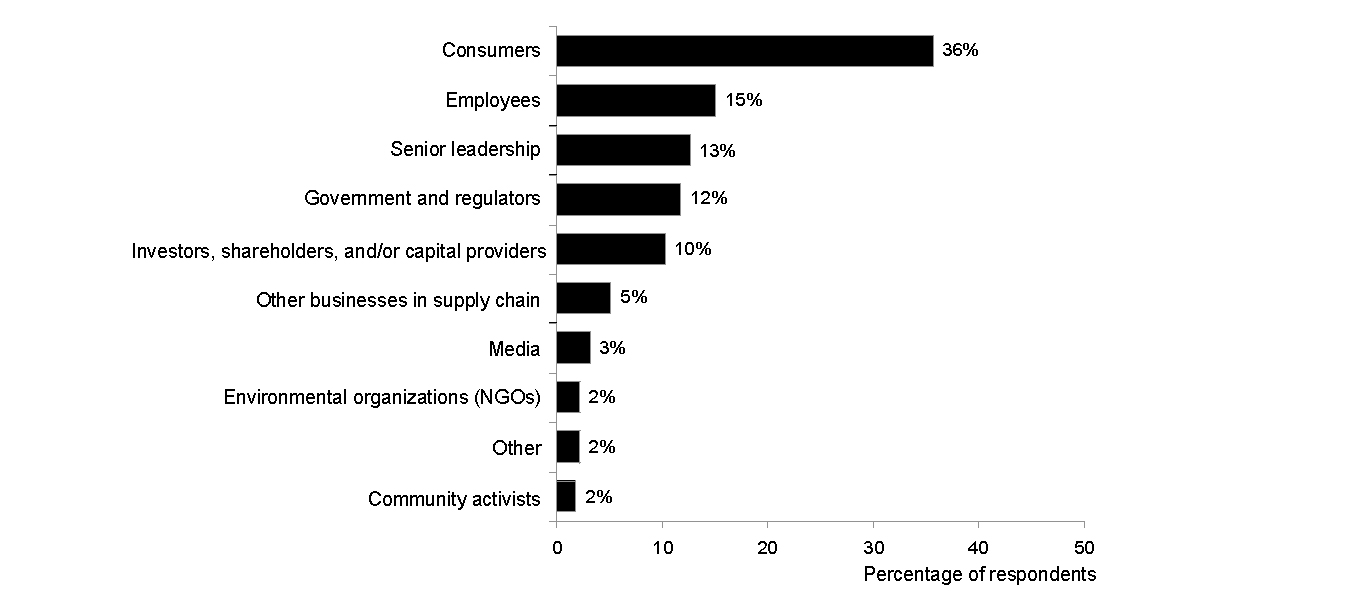

- Consumer Concerns. Fifty-eight percent of respondents in the broader survey group cited consumer concerns as having a significant impact on their companies.4 By contrast, although interviewees in the thought leader group acknowledged that consumer awareness is a reality that businesses must confront, they cited other drivers — such as climate change and other ecological forces — as more pressing.

- Employee Interest. Rounding out the top three drivers was employee interest in sustainability; 56 percent of respondents in the broader survey group selected it as an issue having a significant impact on their company.5 Yet among the thought leader group, employee interest was deemed a far less significant issue. This group, however, consistently cited enhanced recruitment, retention, and engagement — and other employee-related issues — as major benefits of addressing sustainability.

A Better Place: Charging Ahead in Favorable Regulatory Climates

Backstory: Better Place saw a future in electric cars and a demand for ways to recharge them. But how soon will electric charging stations make sense?

Challenge: What’s the fastest way to bring the electric “filling station” — a technology of the future — to market?

Key moves: Shai Agassi founded Better Place in 2007, on a straightforward rationale: Oil is finite, petroleum prices would inevitably rise, and global warming had created the impetus to reduce carbon emissions. Electric cars will be part of the emissions-reduction answer, as long as they have refilling stations.

Still, there was a big gap between that knowledge and the kind of favorable policies needed to create a critical mass of electric cars, at least in most markets.

So Better Place decided to analyze which geographies had already made political and cultural strides toward favoring electric vehicles — in essence, “outsourcing” its work on regulatory policy change to communities where it was already under way.

Among Better Place’s criteria for identifying hospitable locations for operation were that the public had to be receptive to electric cars, therefore creating an underlying market, and the government had to be creating a political climate to bring electric transportation to life. At the top of the list of nations was Israel, which wants all new cars to be electric by 2020. Urban centers in the nation are also less than 150 kilometers apart (about 90 miles) and 90 percent of car owners drive less than 70 kilometers per day, perfect for a short-haul electric vehicle. Add on gasoline taxes and a burgeoning wind industry and Israel appeared the perfect habitat to nurture electric vehicles — and thus electric refilling stations.

Coming in a close second was Denmark, which has a strong green consumer movement and has committed to cutting carbon emissions by 21 percent by 2012. Better Place also partnered with the city of Cogenhagen for the rapid deployment of electric recharging stations. In addition to these two leading-edge countries, the company is working in Australia, the United States (Los Angeles), and Japan to roll out the recharging stations.

Impact: By identifying favorable locations, Better Place is accruing a competitive advantage in removing a major barrier to the widespread adoption of electric cars. It has also positioned itself to be the first to reap the benefits when battery pack recharging facilities and infrastructure are more universally accepted by having proof-of-concept in hand in leading-edge nations.

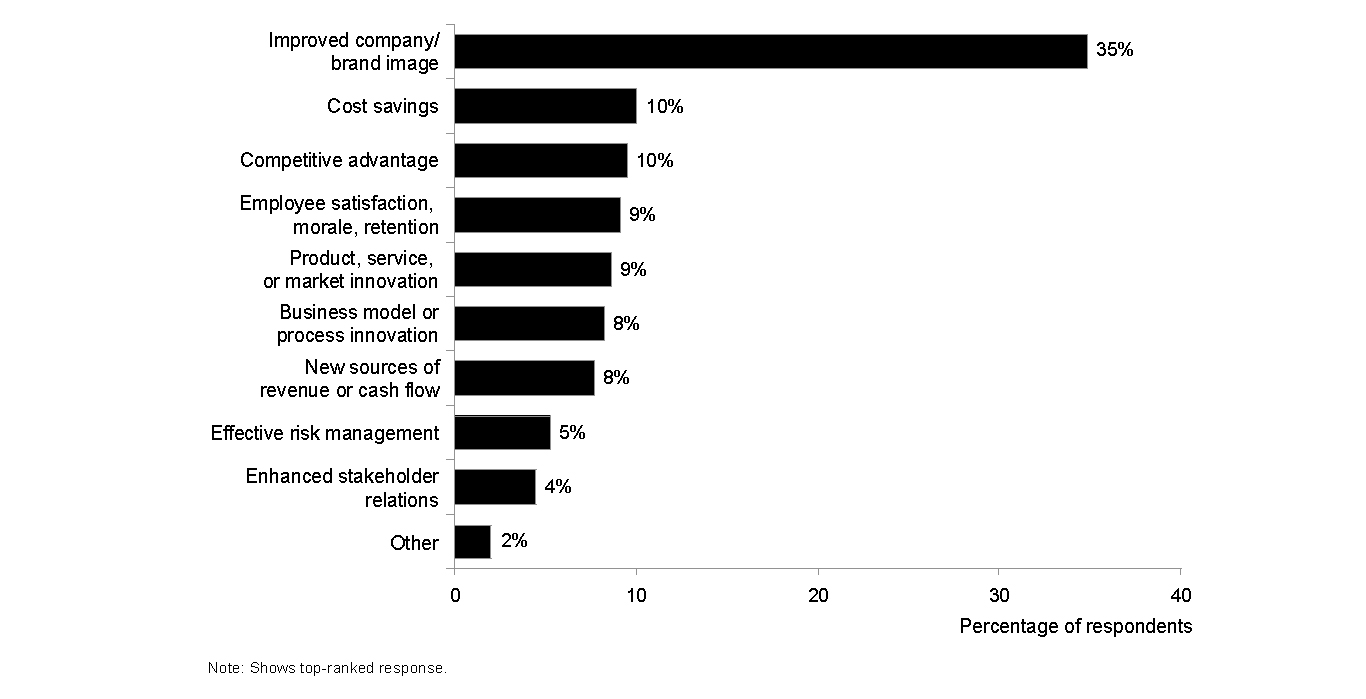

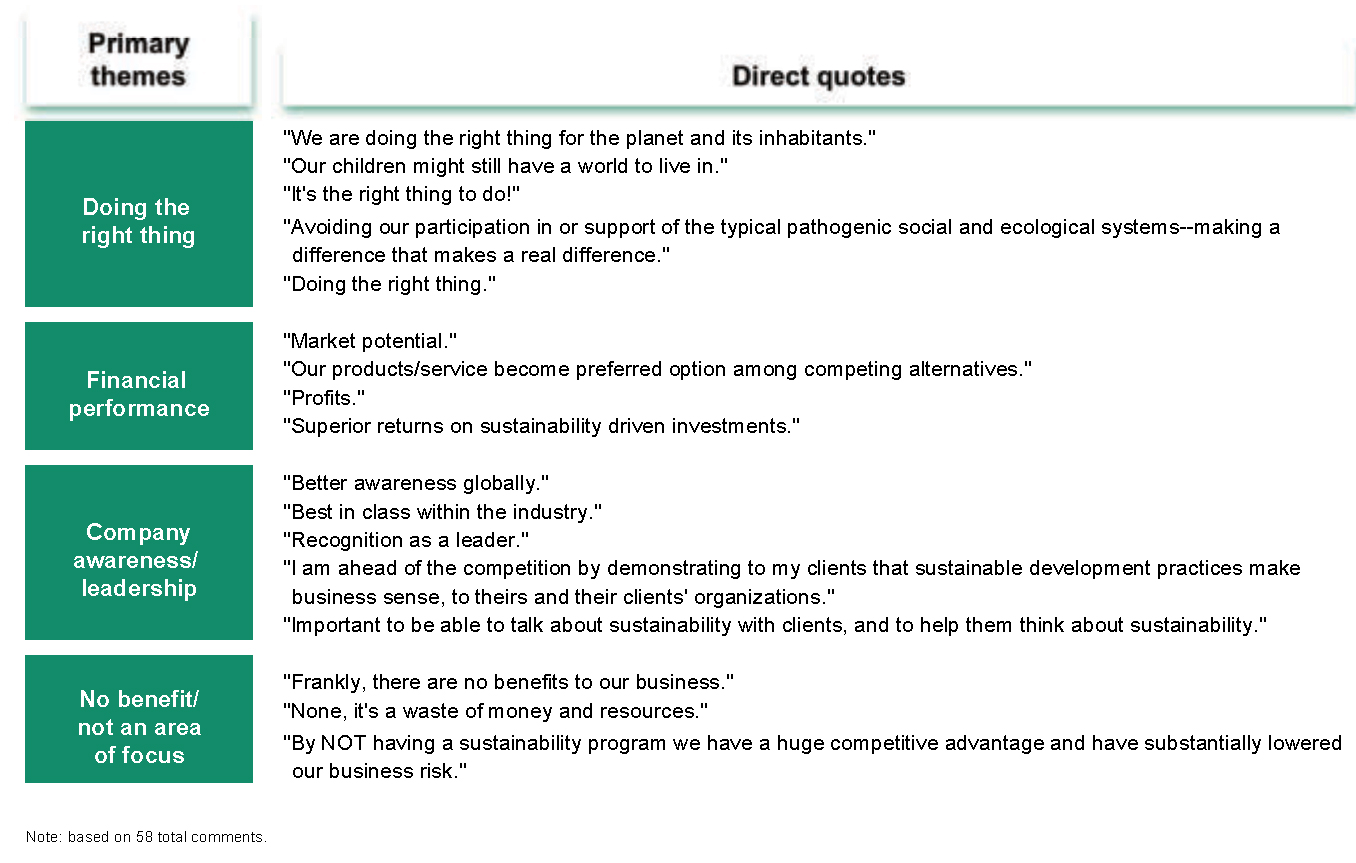

By a wide margin, respondents in the broader survey group identified the impact on a company’s image and brand as the principal benefit of addressing sustainability. (See Exhibit 3.) But interviewees in the thought leader group rarely cited this factor (or when they did, they described it as a second-order benefit), emphasizing instead a broad continuum of rewards that were grounded more in value creation — particularly sustainability’s potential to deliver new sources of competitive advantage. Several thought leaders offered other provocative ideas about the potential benefits of addressing sustainability. For example, some thought leaders suggested that leadership in sustainability might be viewed as a proxy for management quality.

The majority of the respondents in the broader survey group did not share the views espoused by a small core of skeptics. Most survey respondents were convinced that sustainability is currently relevant to their companies. But depending on the questions asked, approximately 5 to 10 percent of the survey respondents expressed doubts.6 Those doubts were centered largely on the following three basic arguments:

- Sustainability issues are not real or material. “All groups talk about the issue, but solely from a politically correct viewpoint,” said an executive at a medium-size multinational company. “Behind the sustainability ‘chatter,’ no one is willing to take any action or invest any time in the matter.”

- Business does not have a role, in general, in addressing sustainability issues. The chairman of a Latin American consumer retail company told us, “My only objective is [a high] return on equity, and I hope that the CEOs who manage the companies in which I invest my savings reason just as I do.”

- Sustainability poses no material opportunities (or threats) to the company. A related argument we heard was that even if sustainability poses opportunities or threats, they are minor, particularly when compared with those related to other investments companies could make. An executive at a European financial services company explained simply, “Sustainability has no impact on our business.”

These views may reflect legitimate doubts; they may also reflect a misunderstanding or misinterpretation of sustainability. For example, we have observed several companies that express many of the arguments listed above — but that are redesigning their products and business processes to have a lighter environmental footprint because it “makes good business sense.”

Some Companies Are Acting Decisively and Winning

“People (in our company) are thrilled when they feel like they can be part of the solution.”

Chris Page director of climate and energy strategy, Yahoo

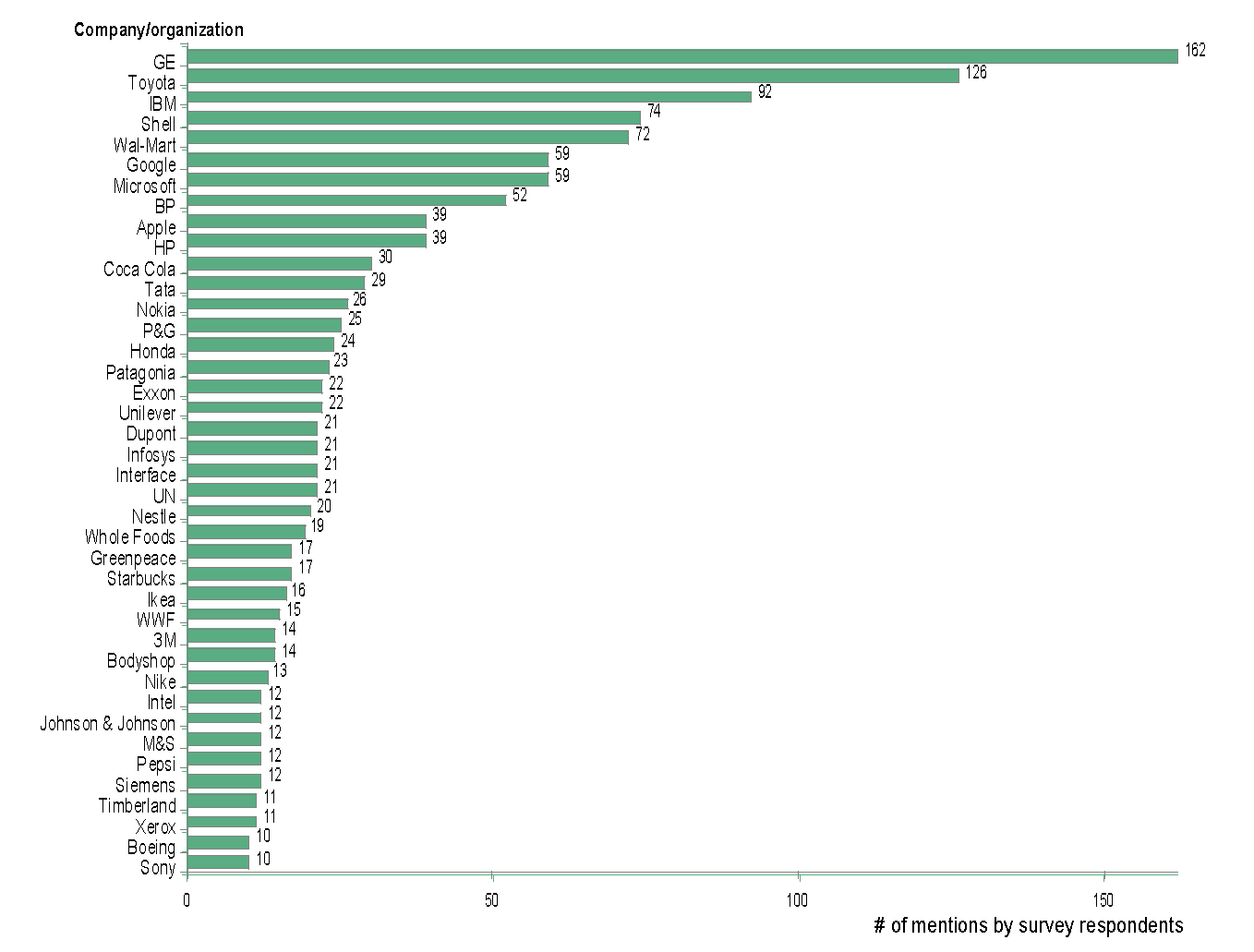

While the vast majority of companies have yet to commit aggressively to sustainability, our survey and interviews confirmed that there are noteworthy exceptions. The group of so-called first-class companies in sustainability, as identified by survey respondents, is populated by the usual suspects often highlighted in business articles, reports, books, and sustainability indexes. The top five cited most often by survey respondents were GE, Toyota, IBM, Shell, and Wal-Mart.7 But some lesser-known names also surfaced, such as Rio Tinto, Better Place, and IWC (International Watch Company). In aggregate, these companies are demonstrating that a sustainability strategy can yield real results. (For more about Nike — one of the companies that our survey respondents cited most often as a first-class company — and the steps that it has taken in sustainability, see the Mini-Case “Nike: From Labor-Practice Compliance to Design Offensive.”)

Nike: From Labor-Practice Compliance to Design Offensive

Backstory: Stung by a campaign against its labor practices in the 1990s, Nike embarked on a long process ultimately to reinvent its operations and meet broad sustainability metrics by 2020.

Challenges: Can you move beyond “compliance” and capitalize on sustainability by integrating it into the fabric of a company — from design and manufacturing to the supply chain?

Key moves: Nike began taking a deep look at its operations in the early 1990s, after it faced a firestorm of criticism over labor practices at its Asian suppliers. The early efforts were siphoned onto a team focused on compliance and social responsibility.

A turning point came when the team began to ask about the long-term implications of its product design and manufacturing decisions. Where did the product materials come from? Were they toxic? What happened at the end of a product’s life? Looking into manufacturing, they found it took three shoes’ worth of material to produce just two — one shoe, in effect, ended up as waste at a cost of $700 million a year. As a result, the goal for zero waste got the attention of senior managers. It became one of several long-term goals to reach by 2020 — along with zero toxic materials, closed loop systems and sustainable growth and profitability. Nike also created an in-house index to measure product design against these goals.

Then it began reinventing the design process. If the athletic shoe was streamlined to cut waste and material by reducing the number of components, the production efficiencies could offset the cost of more sustainable materials.

Impact: Nike began implementing zero waste and streamlined production around its Considered line of athletic footwear and apparel. That leading-edge line now comprises 15 percent of its products. The company aims to convert all athletic shoes to Considered standards by 2011, all clothing by 2015, and all equipment like balls, gloves, and backpacks by 2020. Under the new design and production methods, these products reduce waste by up to 67 percent, cut energy use by 37 percent, and slash solvent use by 80 percent compared with other Nike products.

“I think the first reward is around the ability to attract and motivate the very best people. It is extraordinary how attractive BP’s alternative energy business is for people coming into the company. And where — certainly up until very, very recently — many good graduates would not consider a career in the oil industry, they will consider a career in an alternative energy business, even if it is inside an oil company.”

Vivienne Cox, former executive vice president, BP, and former chief executive officer, BP Alternative Energy

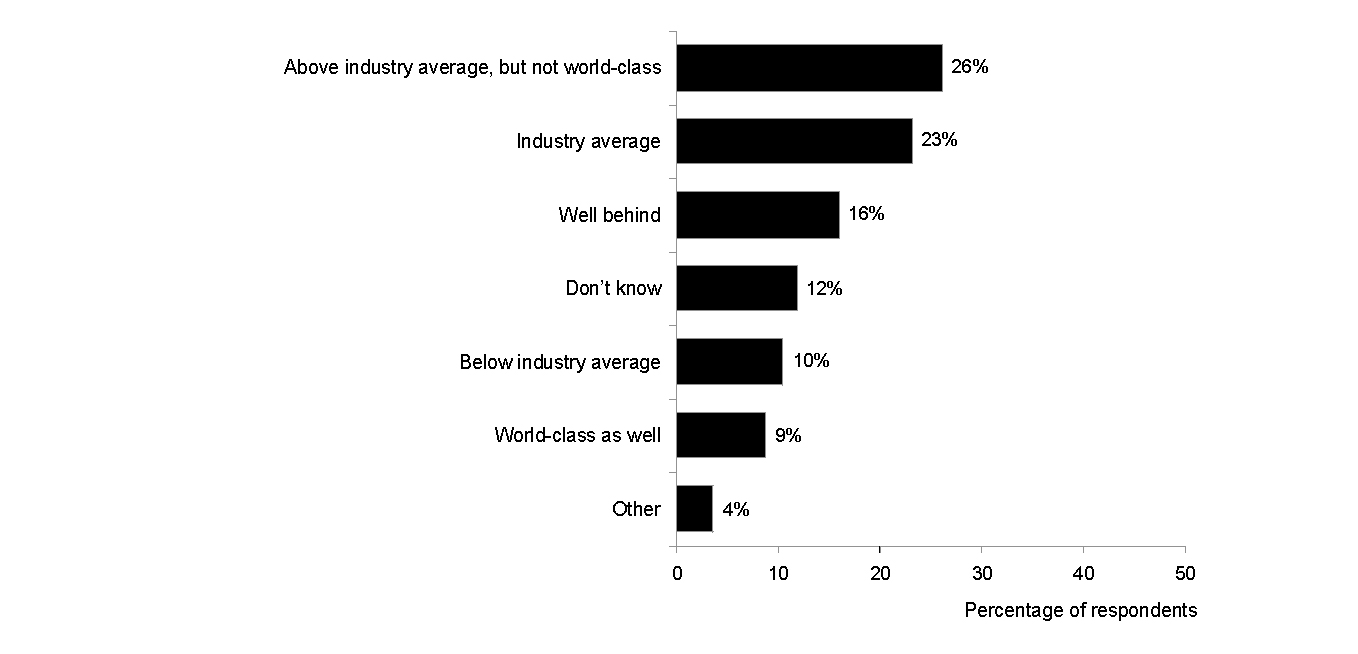

Most Companies Either Are Not Acting or Are Falling Short on Execution

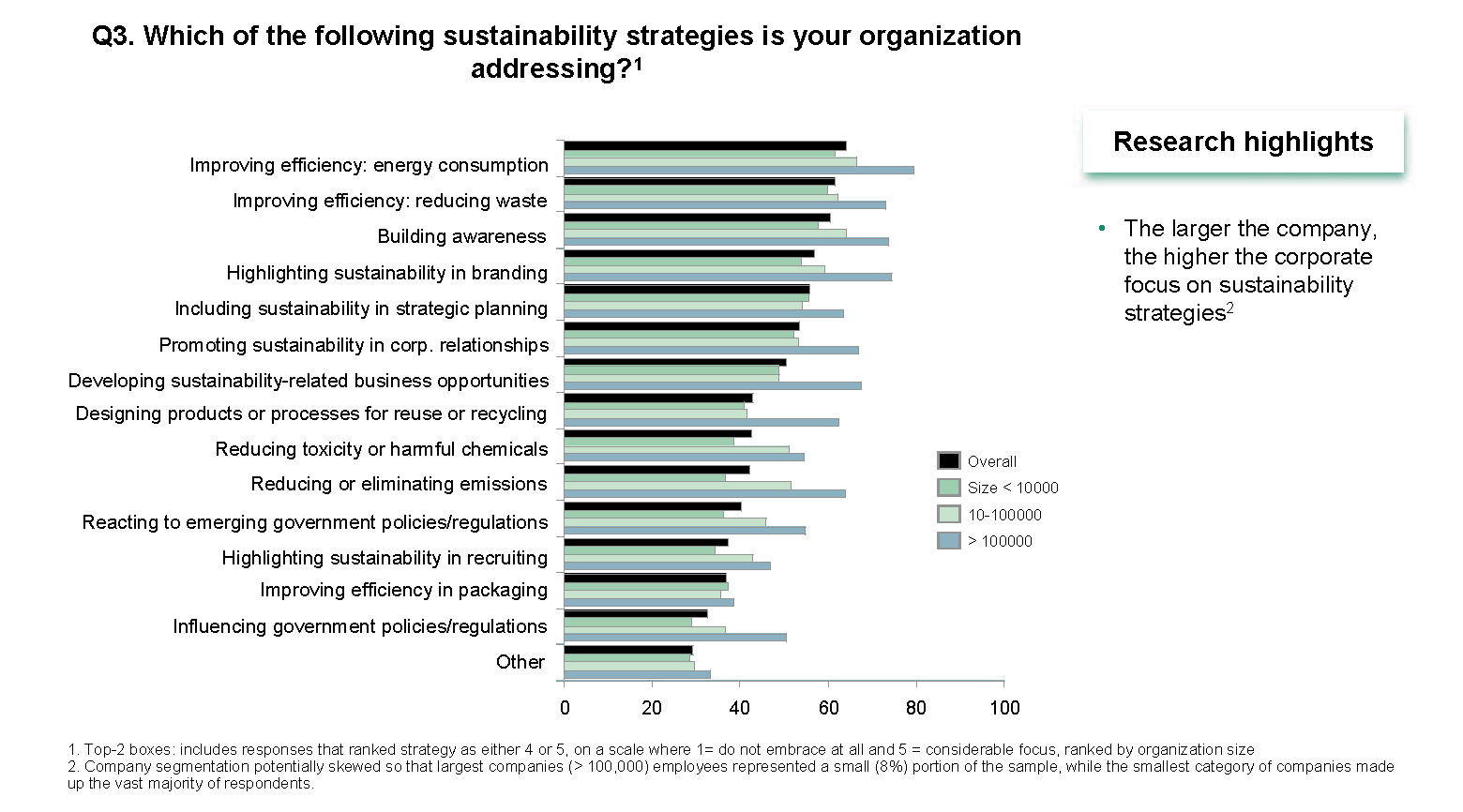

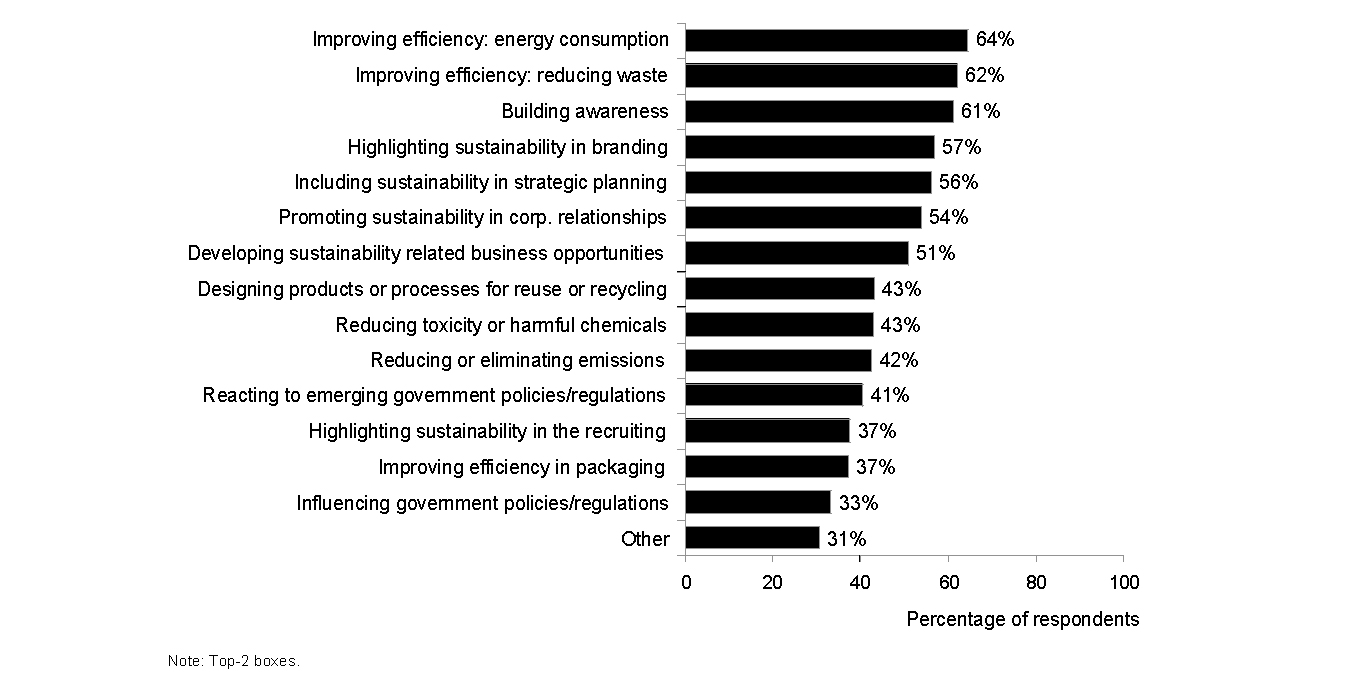

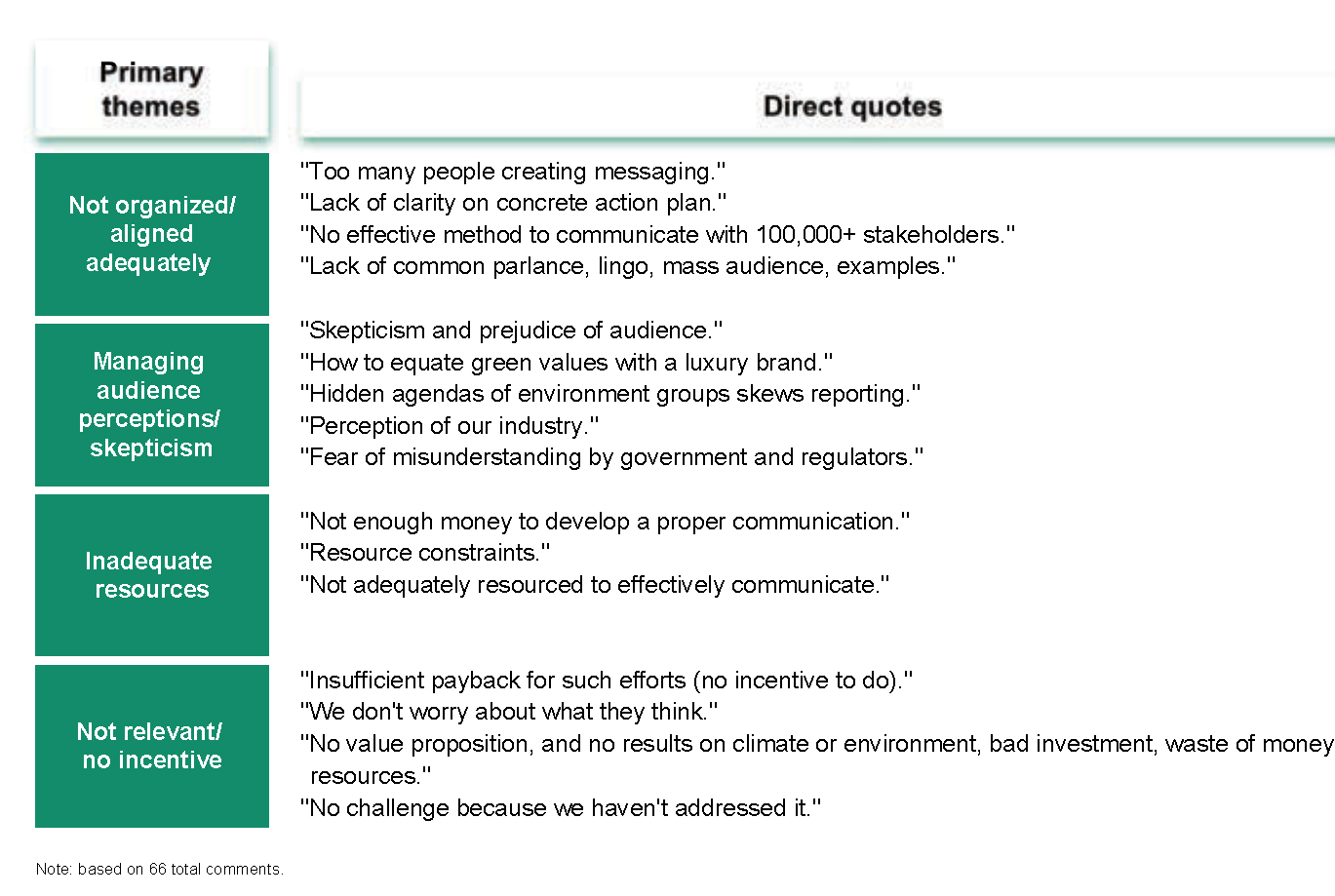

Our survey and interviews demonstrated that there is a large degree of consensus regarding the potential business impact of sustainability. Our research further confirmed that there are stirrings of activity throughout the business realm. But we found a material gap between intent and action at most of the companies we examined. On the one hand, more than 60 percent of the respondents in the broader survey group said that their company was building awareness of its sustainability agenda. On the other hand, most of these companies appeared to lack an overall plan for attacking sustainability and delivering results. Many of their actions seemed defensive and tactical in nature, consisting of a variety of disconnected initiatives focused on products, facilities, employees, and the greater community. While these efforts might be impressive on some levels, they largely represented only incremental changes to the business.

Clearly, companies can do more to connect their stated intent in sustainability with business impact — and they can do it in a way that maintains explicit links to the bottom line over both the short and long term. But why aren’t they, given that they believe sustainability will materially affect their business?

Why Decisive — and Effective — Corporate Action Is Lacking

The thought leader group and the survey respondents alike viewed sustainability as a unique business issue, both strategically and economically. They embraced the following principles:

The best way to get people to take sustainability seriously is to frame it as it really is: not only a challenge that will affect every aspect of management but, for first movers, a source of enormous competitive advantage.

Richard Locke, deputy dean and professor of entrepreneurship, MIT Sloan School of Management

- Sustainability has the potential to affect all aspects of a company’s operations, from development and manufacturing to sales and support functions.

- Sustainability also has the potential to affect every value-creation lever over both the short and longer term. Rarely has a business issue been viewed as having such a broad scope of impact.

- There is mounting pressure from stakeholders — employees, customers, consumers, supply chain partners, competitors, investors, lenders, insurers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), media, the government, and society overall — to act.

- The solutions to the challenges of sustainability are interdisciplinary, making effective collaboration with stakeholders particularly critical.

- Decisions regarding sustainability have to be made against a backdrop of high uncertainty. Myriad factors muddy the waters because of their unknown timing and magnitude of impact. Such factors include government legislation, demands by customers and employees, and geopolitical events.

These principles make sustainability a uniquely challenging issue for business leaders to manage and address effectively.

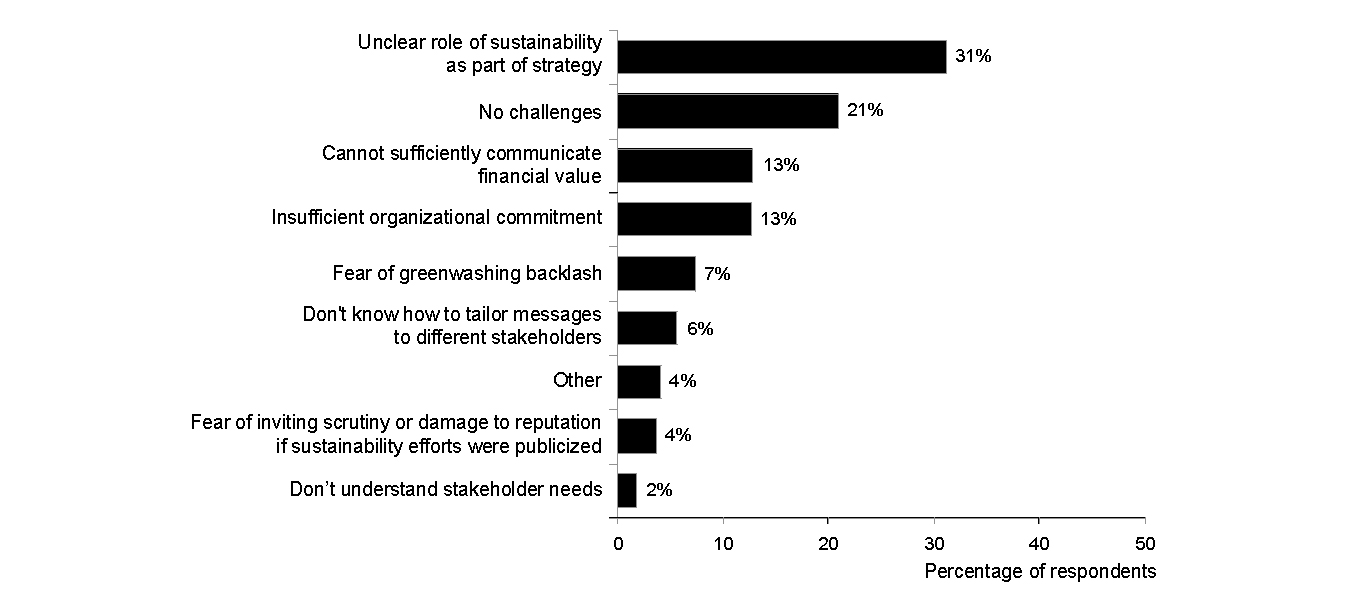

Three Major Barriers Impede Decisive Corporate Action

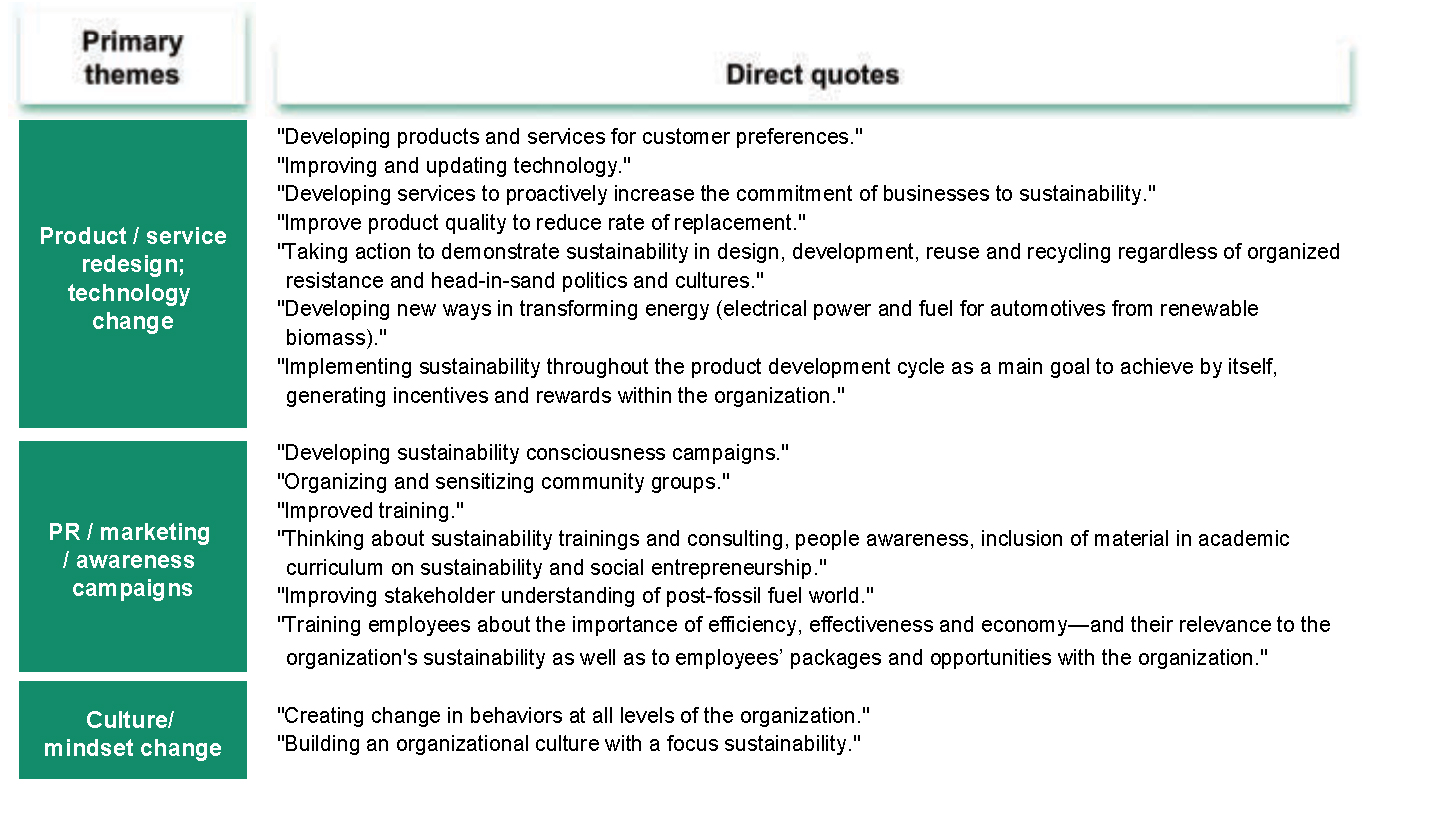

There are many reasons why companies are struggling to tackle sustainability more decisively. But our research points to three root causes. First, companies often lack the right information upon which to base decisions. Second, companies struggle to define the business case for value creation. Third, when companies do act, their execution is often flawed.

“[Pursuing sustainability] opens up a broader set of options. For example, there are places where the fact that we have a solar business — or are involved in carbon capture and storage — changes the conversations even around the oil and gas business. And therefore, sustainability efforts are opening up a different dialogue than the one that would occur if we were just a traditional oil and gas company.”

Vivienne Cox, former executive vice president, BP, and former chief executive officer, BP Alternative Energy

Some companies don’t understand what sustainability is — and what it means to the enterprise. Our survey revealed that many business leaders lack a complete understanding of what sustainability really means to their company, largely because of some key underlying information gaps.

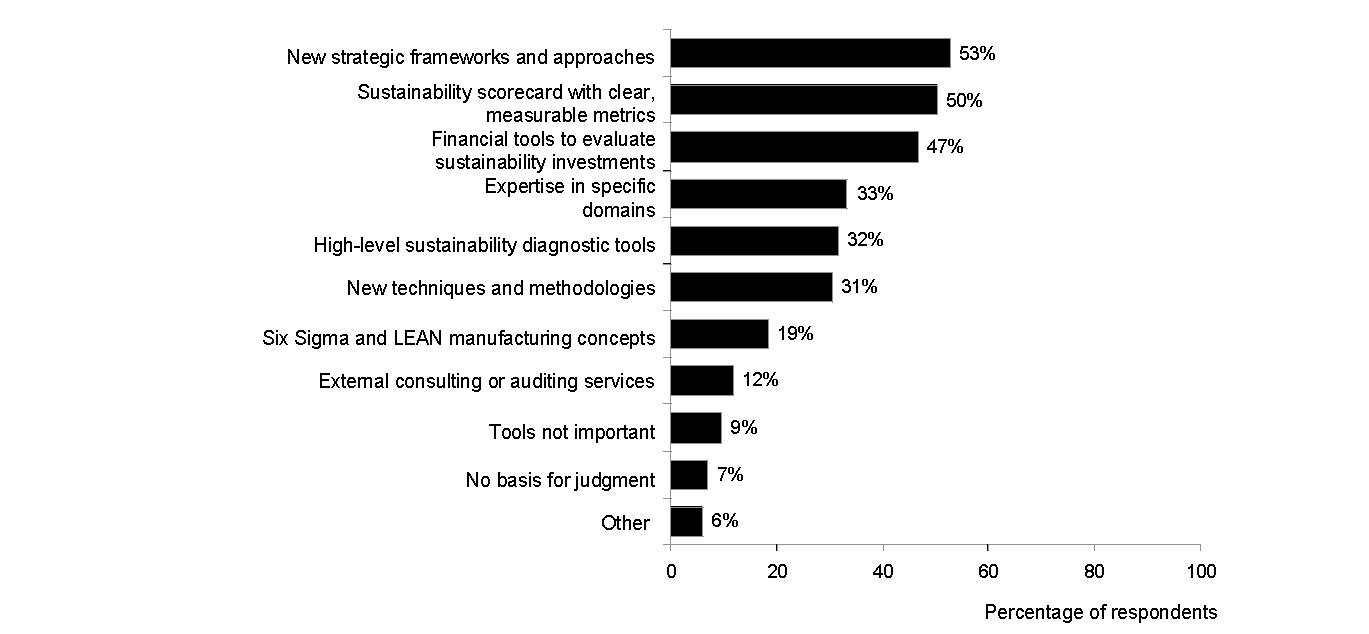

- Managers lack a common fact base about the full suite of drivers and issues that are relevant to their company and industry. More than half of the respondents in the broader survey group stated a need for better frameworks for understanding sustainability.

- As mentioned earlier, companies do not share a common definition or language for discussing sustainability — some define it very narrowly, some more broadly, others lack any corporate definition.

- The goal or “prize” of concerted action is often defined too loosely and not collectively understood within the organization. And there’s often no understanding of how to measure progress once actions are undertaken.

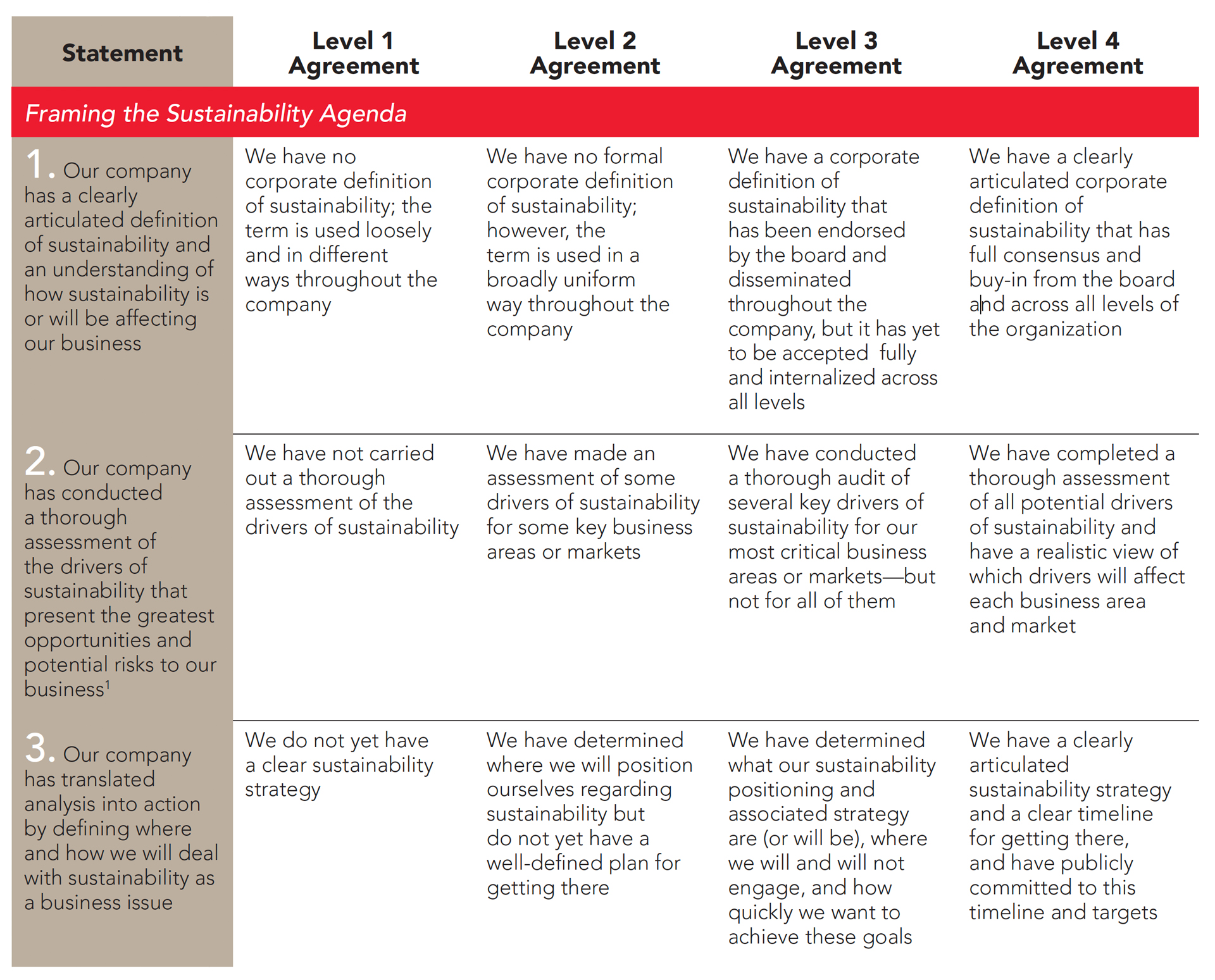

All of these issues point to a critical need for a thorough and structured gathering and sharing of basic facts about sustainability as a first step toward helping managers to be more decisive in the choices they face. To aid managers in this difficult task, we have developed a simple framework for understanding the drivers and impacts of sustainability efforts and for helping to add clarity to the boardroom discussion on the appropriate actions for each company. (See Exhibit 4 for one view on framing sustainability for business.)

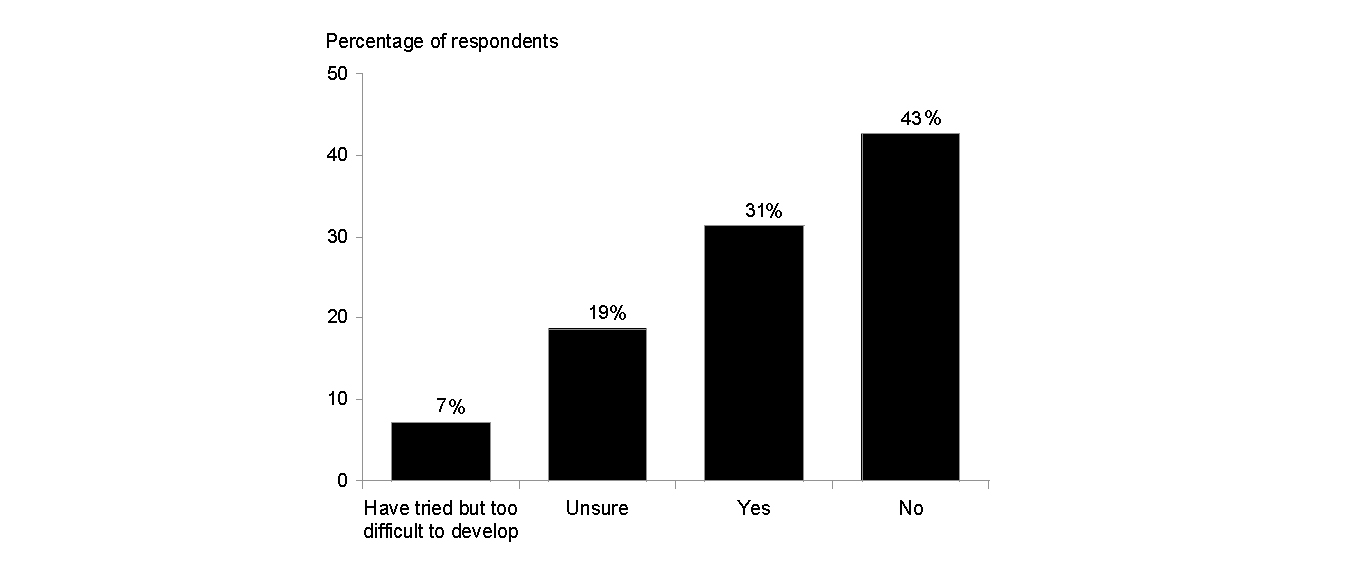

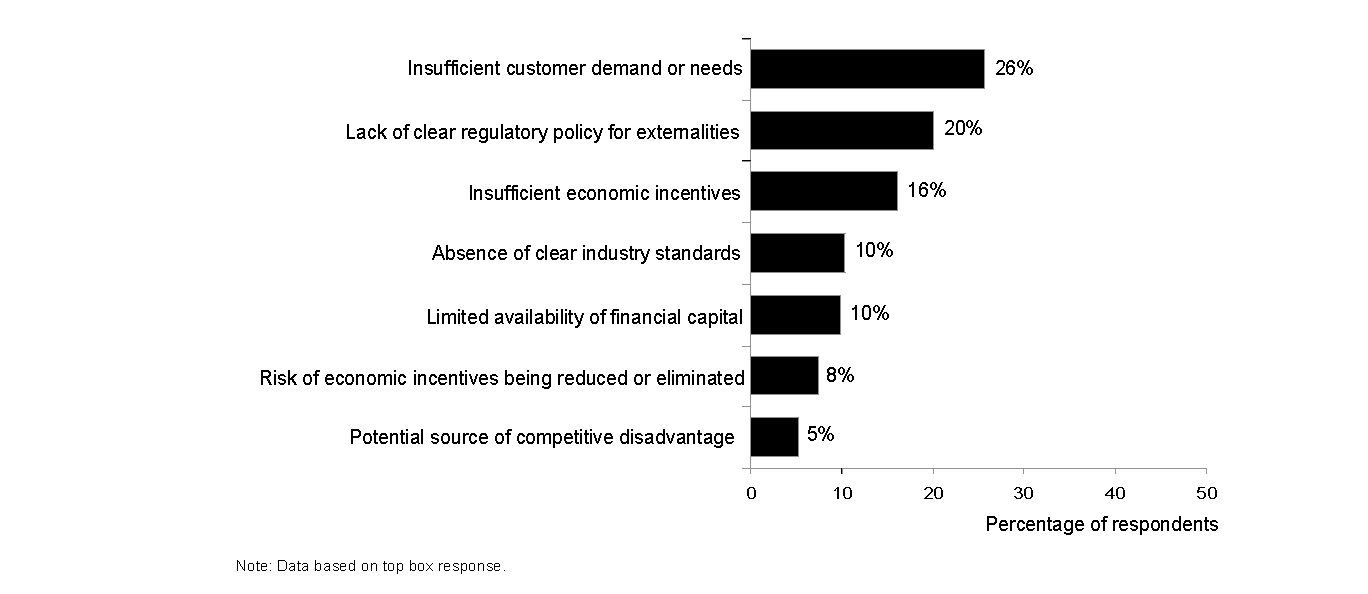

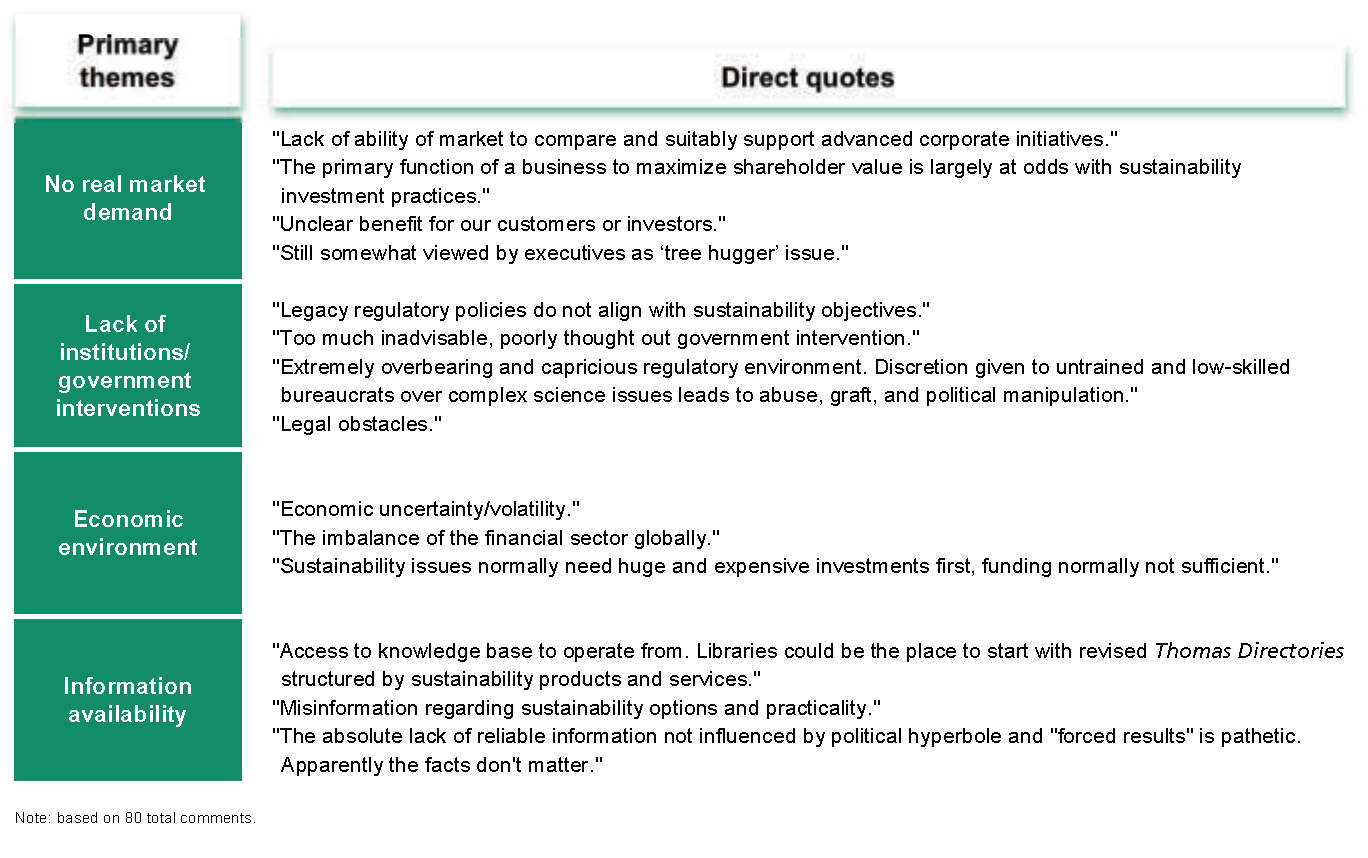

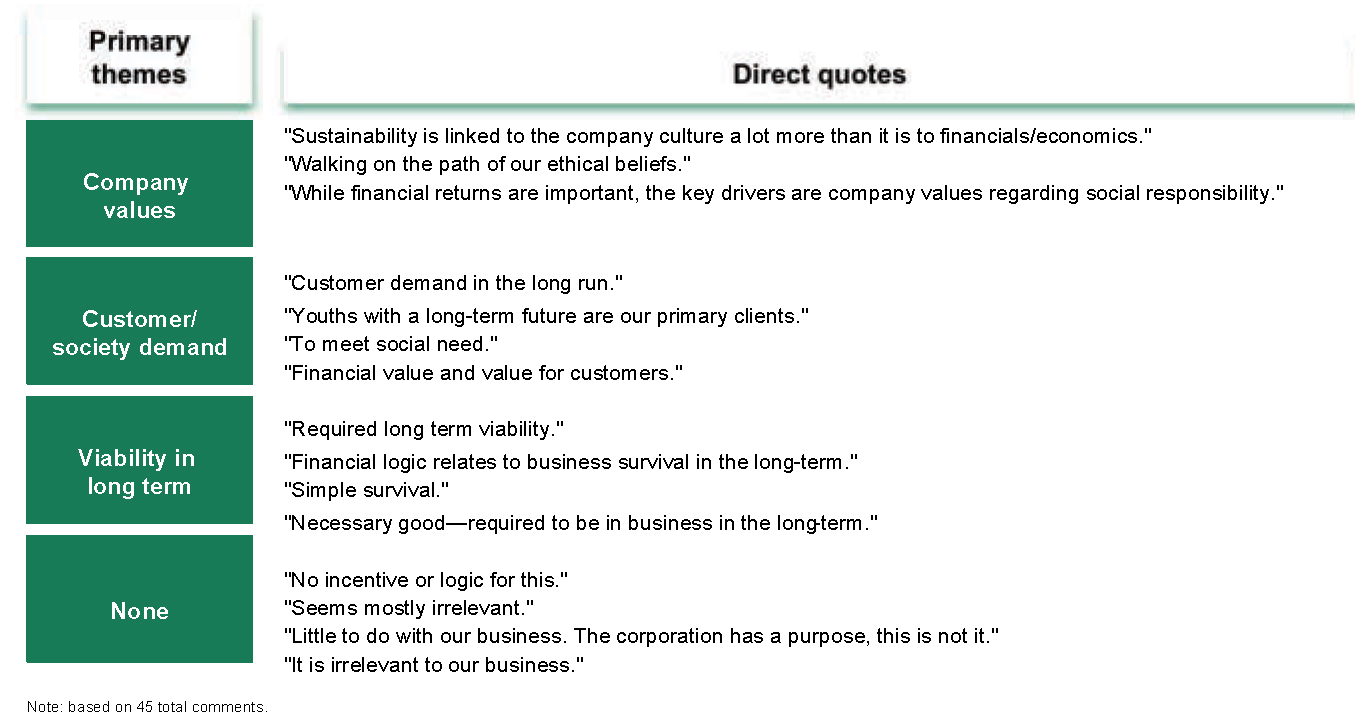

Some companies have difficulty modeling the business case — or even finding a compelling case — for sustainability. Most survey respondents who considered themselves experts in sustainability, as well as most of the interviewees in the thought leader group, said that their company had found a compelling business case — one that reflected multiple tangible and intangible costs and benefits — for sustainability. (See Exhibit 5 for a summary of sustainability’s potential impact when viewed through the lens of shareholder value creation.)

“Green can save you a lot of money — not two or three years from now, but now.”

Catherine Roche, partner and managing director, The Boston Consulting Group

The majority of survey respondents overall, however, disagreed: almost 70 percent said that their company did not have a strong business case for sustainability. Of these respondents, 22 percent claimed that the lack of a business case presented their company with its primary barrier to pursuing sustainability initiatives.

Why do companies struggle in their efforts to develop the business case for sustainability? Our survey uncovered three main challenges that trip up companies. The first challenge is forecasting and planning beyond the one-to-five-year time horizon typical of most investment frameworks. It is easy to assert that sustainability is about taking a long-term view. But in practice, calculating the costs and benefits of sustainability investments over time frames that sometimes span generations can be difficult with traditional economic approaches. This is further exacerbated by the short-term performance expectations of investors and analysts. The framework mentioned above can provide a company’s board, shareholders, employees, and investors with a starting point for assessing the potential of short- and long-term moves in sustainability to create value.

“Sustainability must be an integral part of strategy — not an add-on.”

Ramón Baeza, senior partner and managing director and topic leader in the sustainable development sector, The Boston Consulting Group

The second challenge is gauging the systemwide effects of sustainability investments. Companies find it difficult enough to identify, measure, and control all of the tangible facets of their business systems. So they often do not even attempt to model intangibles or externalities such as the environmental and societal costs and benefits of their current business activities and potential moves in sustainability. This hinders their ability to get a true sense of the value of investments in sustainability.

The third major challenge is planning amid high uncertainty. Factors contributing to uncertainty include potential changes in regulation and customer preferences. Strategic planning, as traditionally practiced, is deductive — companies draw on a series of standard gauges to predict where the market is heading and then design and execute strategies on the basis of those calculations. But sustainability drivers are anything but predictable, potentially requiring companies to adopt entirely new concepts and frameworks.

“We have specific metrics because in a culture of execution, which is what GE is all about, the only way that ecomagination could survive is if we put some hard metrics around it.”

Steve Fludder, vice president, ecomagination, GE

In general, the thought leader group and also the survey respondents with experience in sustainability believe that clarifying the business case for sustainability may be the single most effective way to accelerate decisive corporate action, since it gets to the heart of how companies decide where they will — and will not — allocate their resources and efforts.

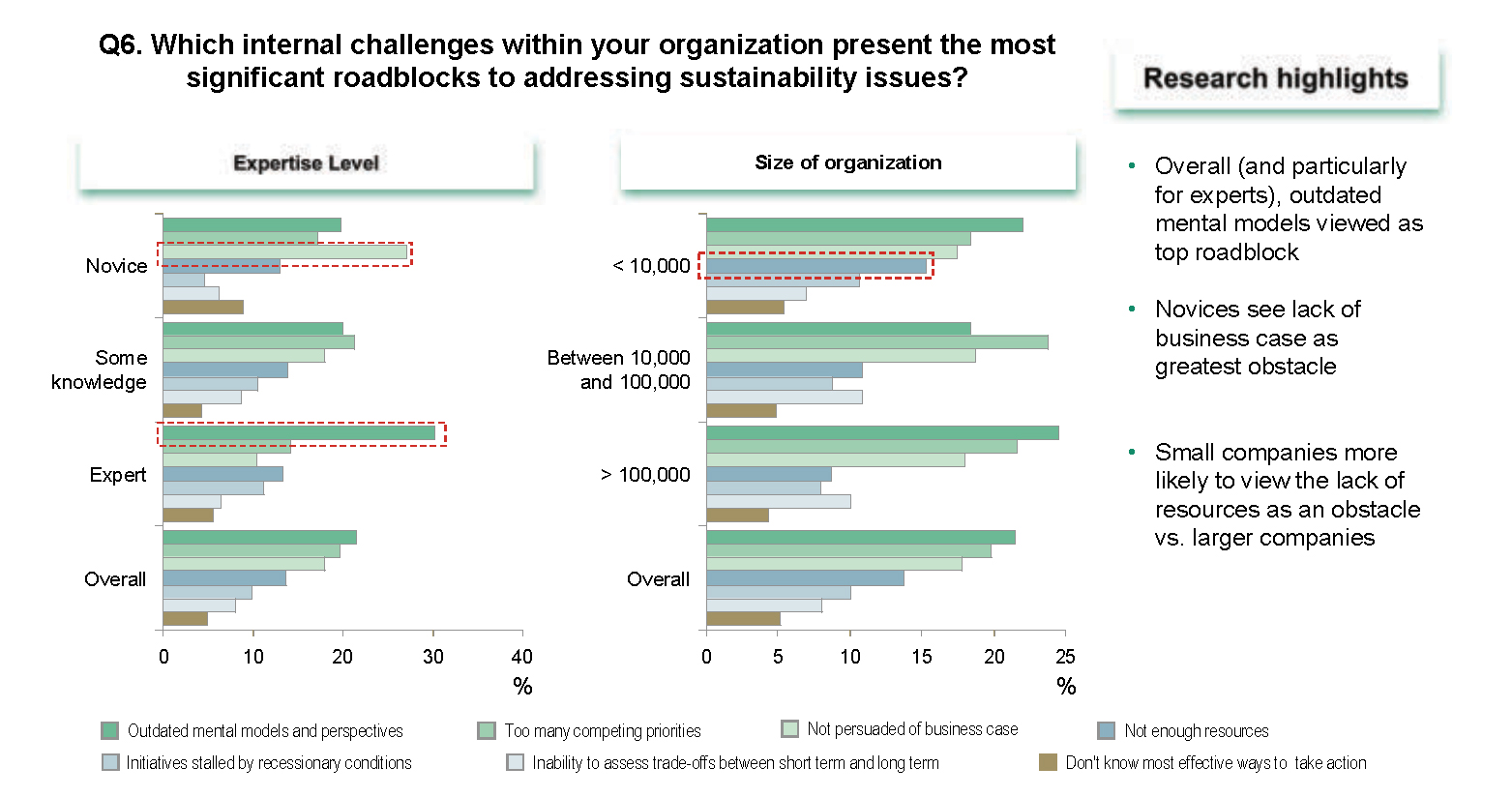

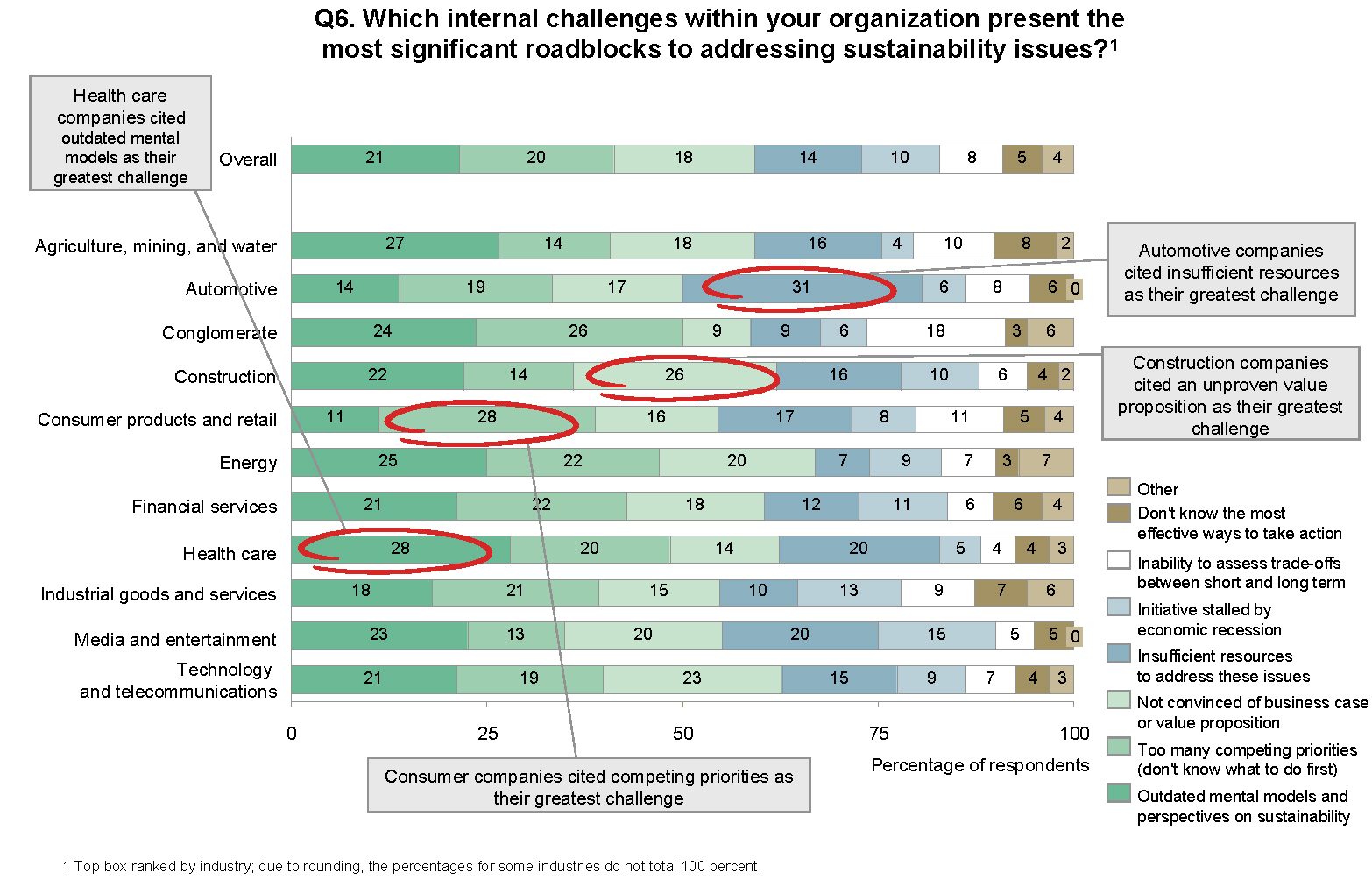

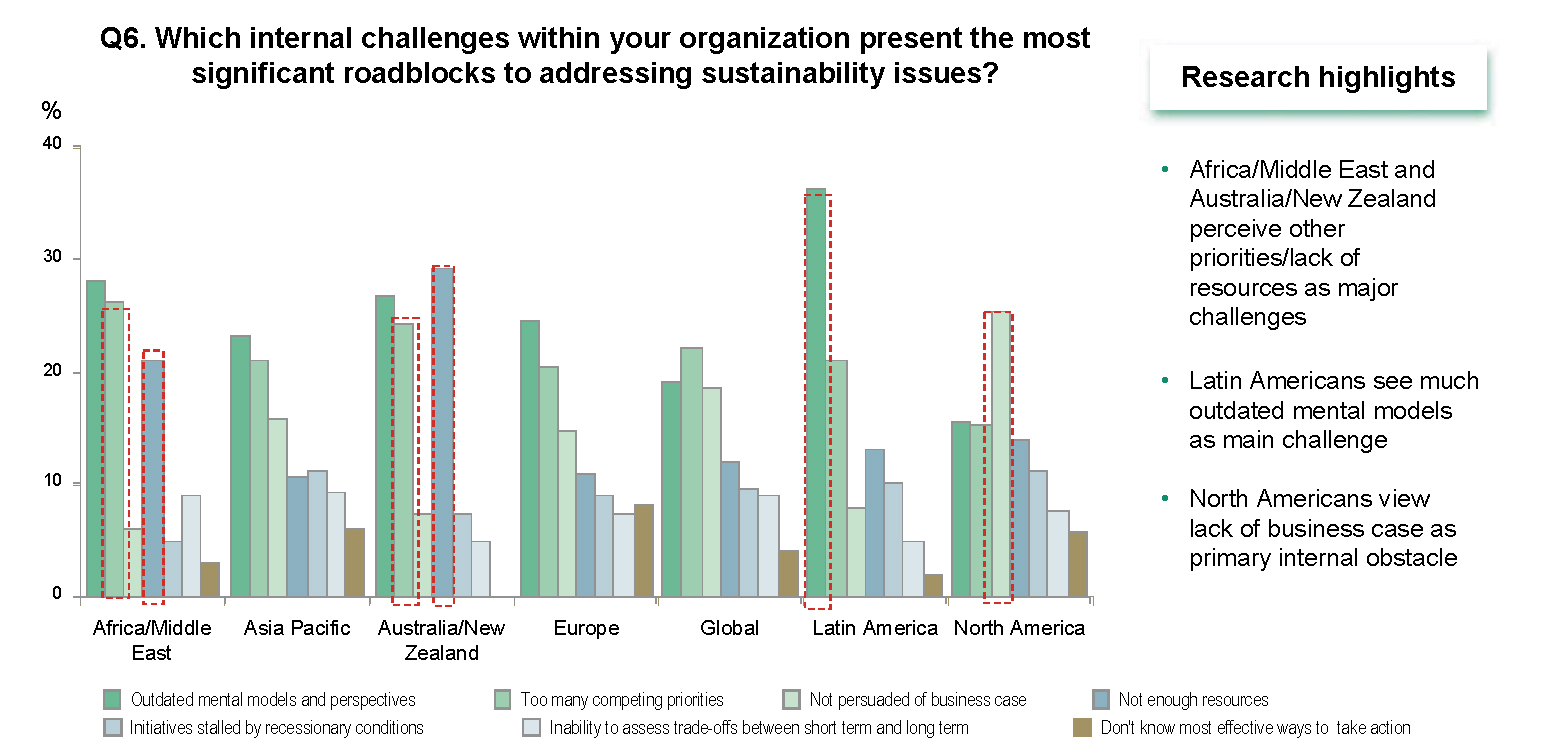

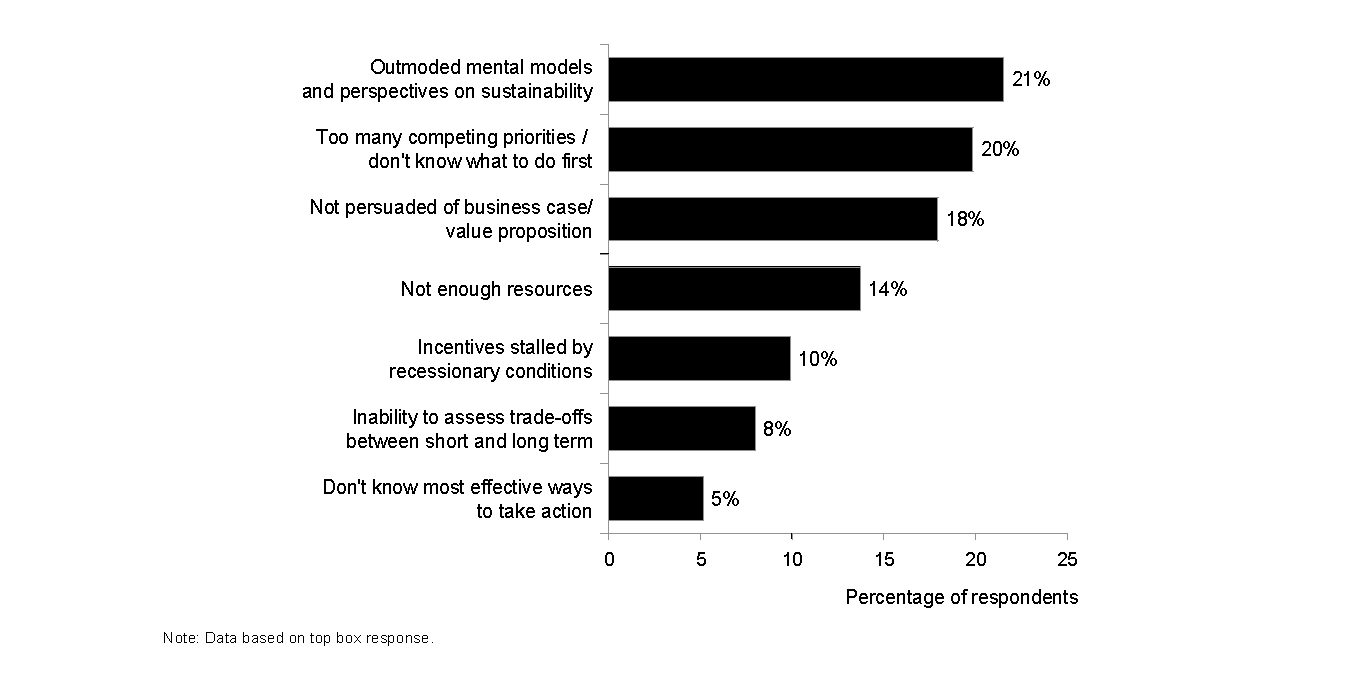

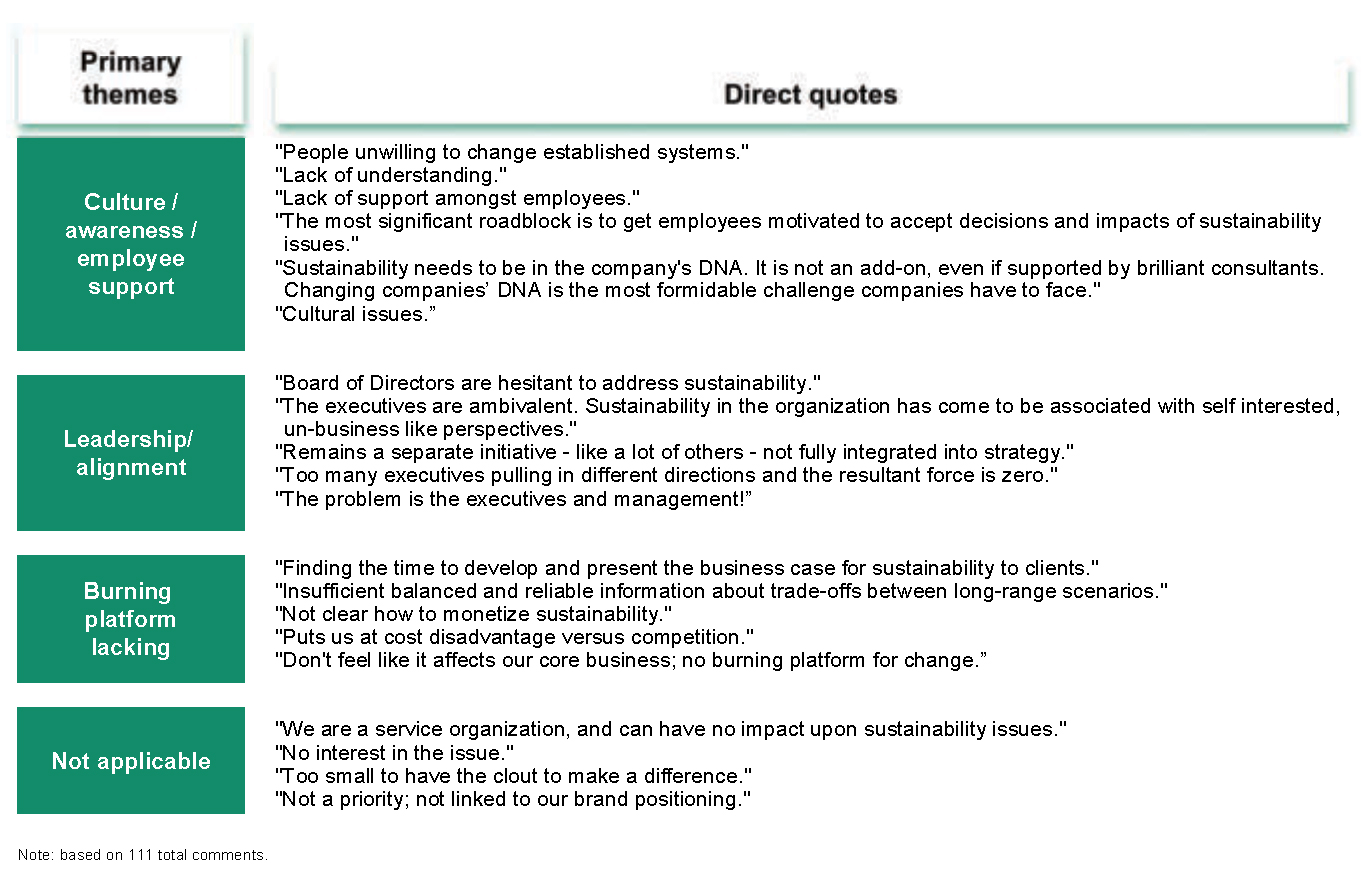

Execution is often flawed. Even if companies surmount the first two hurdles, they often stumble over the third hurdle: execution. While it is still early days in terms of judging the effectiveness of execution in sustainability, our interviews and survey highlighted three main challenges in executing sustainability initiatives. The first is overcoming skepticism in organizations. Indeed, corporate respondents in the broader survey group cited outdated mental models and perspectives as the top internal roadblock to addressing sustainability issues. (See Exhibit 6.) Examples of entrenched mind-sets that respondents cited include views that sustainability is solely “an additional cost” or “a green utopia.”

We need to educate people about systems thinking and help them understand how all of these activities are interdependent and affect each other.”Jeffrey Hollender, chief inspired protagonist and cofounder, Seventh Generation

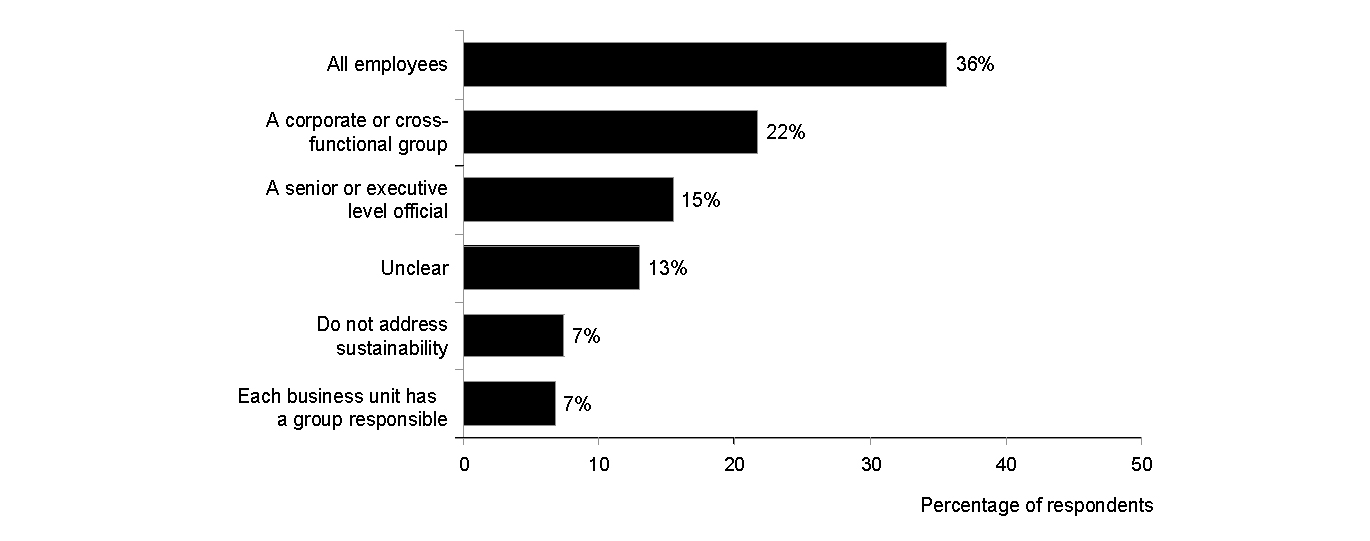

The second challenge in execution is figuring out how to institutionalize the sustainability agenda throughout the corporation. Survey respondents and the thought leader group alike were adamant that top-down vision, commitment, and leadership were critical for success — and that the absence of a top-down commitment was one of the greatest impediments to successful execution. Further, companies were often uncertain about where responsibility for achieving sustainability strategies should or did reside.

“Anticipating what’s coming, such as new greenhouse-gas regulations, is vital. Key energy technologies need to move through the 4Ds: discover, develop, demonstrate, and deploy.”

Graeme Sweeney, executive vice president of future fuels and CO2, Royal Dutch Shell

The third major challenge cited is measuring, tracking, and reporting sustainability efforts. These tasks are especially difficult in light of the fact that consumers and other stakeholders are increasingly demanding complete transparency on sustainability. Companies are often expected to share such information as their carbon footprint and the specifics of their manufacturing practices.

Several of these barriers, it should be noted, will accompany any major change effort in corporate strategy and operations. But they are intensified in the case of sustainability, given the topic’s unique economic and strategic challenges and companies’ limited experience with it.

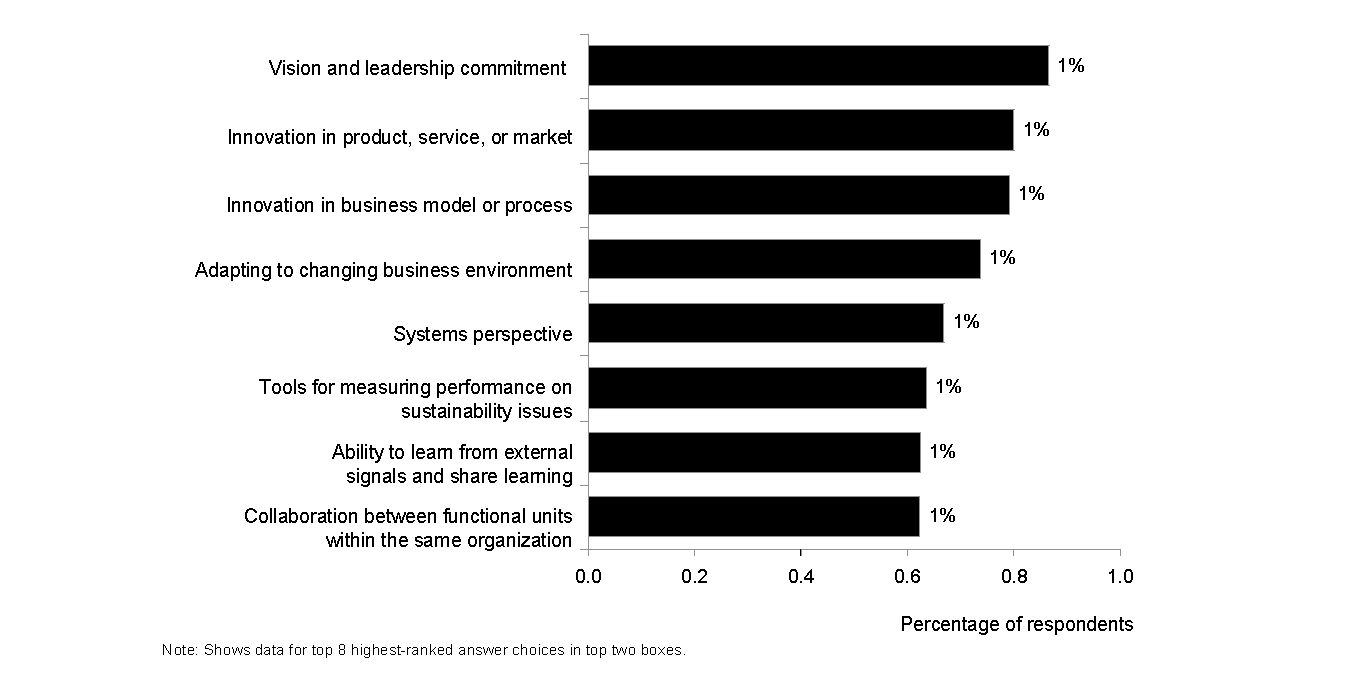

Necessary Capabilities Are in Short Supply

Interestingly, most of the respondents in the broader survey group expressed relatively limited concern about their companies having distinct gaps in technical or operational capabilities needed to address sustainability. We believe, however, that those executives might have underestimated the challenge. According to interviewees in the thought leader group, companies will need to develop and master a multitude of new capabilities and tools — and take a number of actions — if they are to execute their sustainability strategies successfully. We highlight a few of the critical capabilities below:

“Masdar’s typical engagement model is to partner with more experienced organizations. Torresol Energy, London Array, or our Masdar Clean Tech Fund with Credit Suisse are typical examples of such partnerships. Our investment strategy is centered on ‘People, Planet, Profit.’ Besides the obvious commercial benefits that we expect to achieve, we also consider the social and environmental impact of new investments.”

Ziad Tassabehji, director of utilities and asset management, Masdar

- Adopting a broad, systems-thinking approach to their business. Actions could range from deploying frameworks that allow for the modeling of systemwide effects of sustainability initiatives over the long term to forming more-effective partnerships and alliances and working in more concerted ways with stakeholders, regulators, and other influencers.

- Adding scenario-planning capabilities that allow the company effectively to build resilience to unpredictable future environments and external shocks, such as sharp swings in commodity prices.

- Developing tracking, measuring, and reporting capabilities, particularly as the bar for transparency continues to rise.

- Retooling R&D, product development, and sales and marketing to reimagine how products are designed, made, used, and recycled.

- Enhancing capabilities in innovating organizational models and management practices. This includes reorienting incentive and reward systems to promote long-term strategic and tactical thinking and multidisciplinary collaboration. It also includes knowing how and when to partner to achieve maximum advantage.

In the near future, these capabilities and tools may represent table stakes for managers and organizations. Already, many best-in-class companies possess these skills.

Looking Ahead: Seizing Opportunities and Mitigating Risks

As they confront the barriers to pursuing and achieving sustainability, many — if not most — business managers are struggling to understand where their companies are, where they need to go, and how to get there. The examples of leading companies offer a blueprint for how to proceed.

The Sustainability Audit

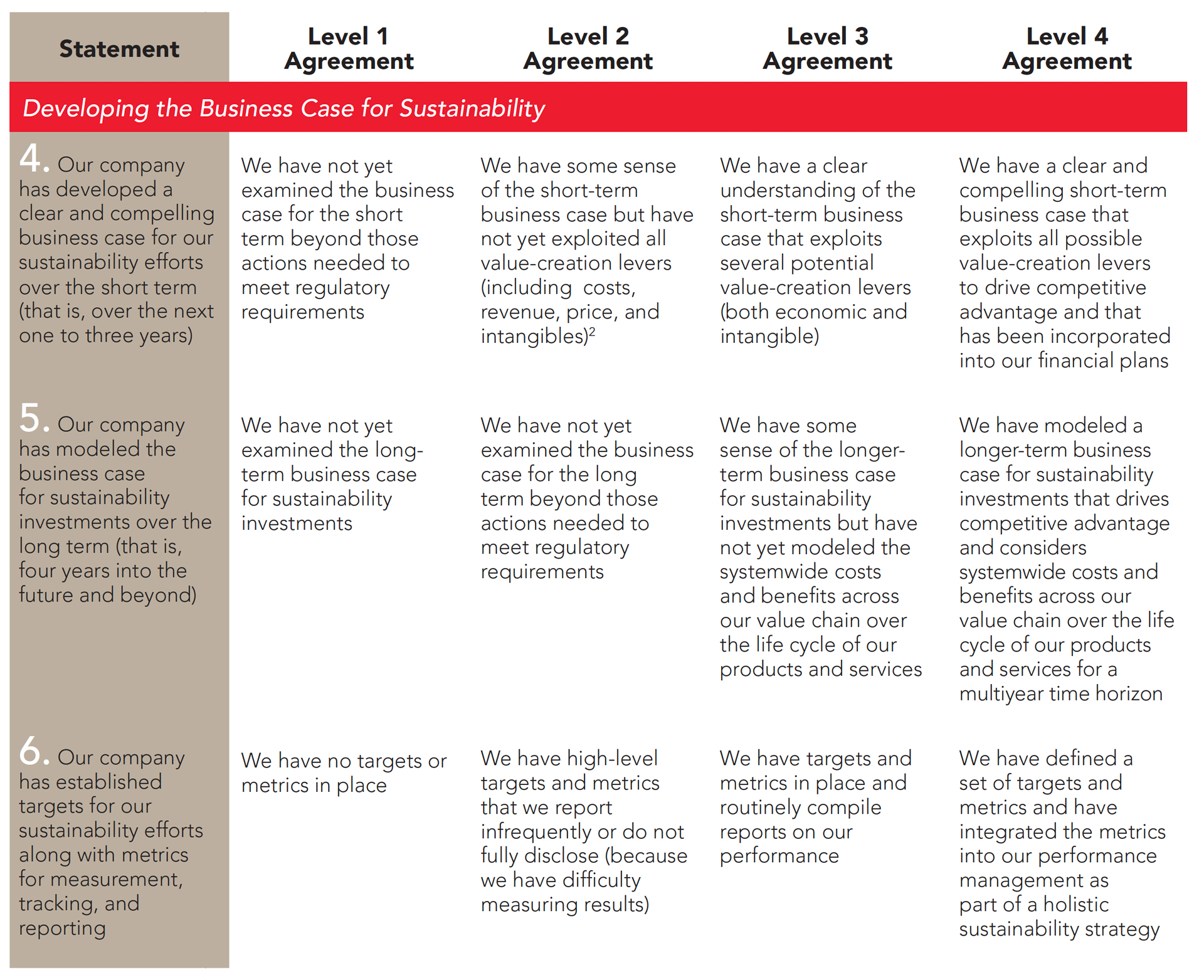

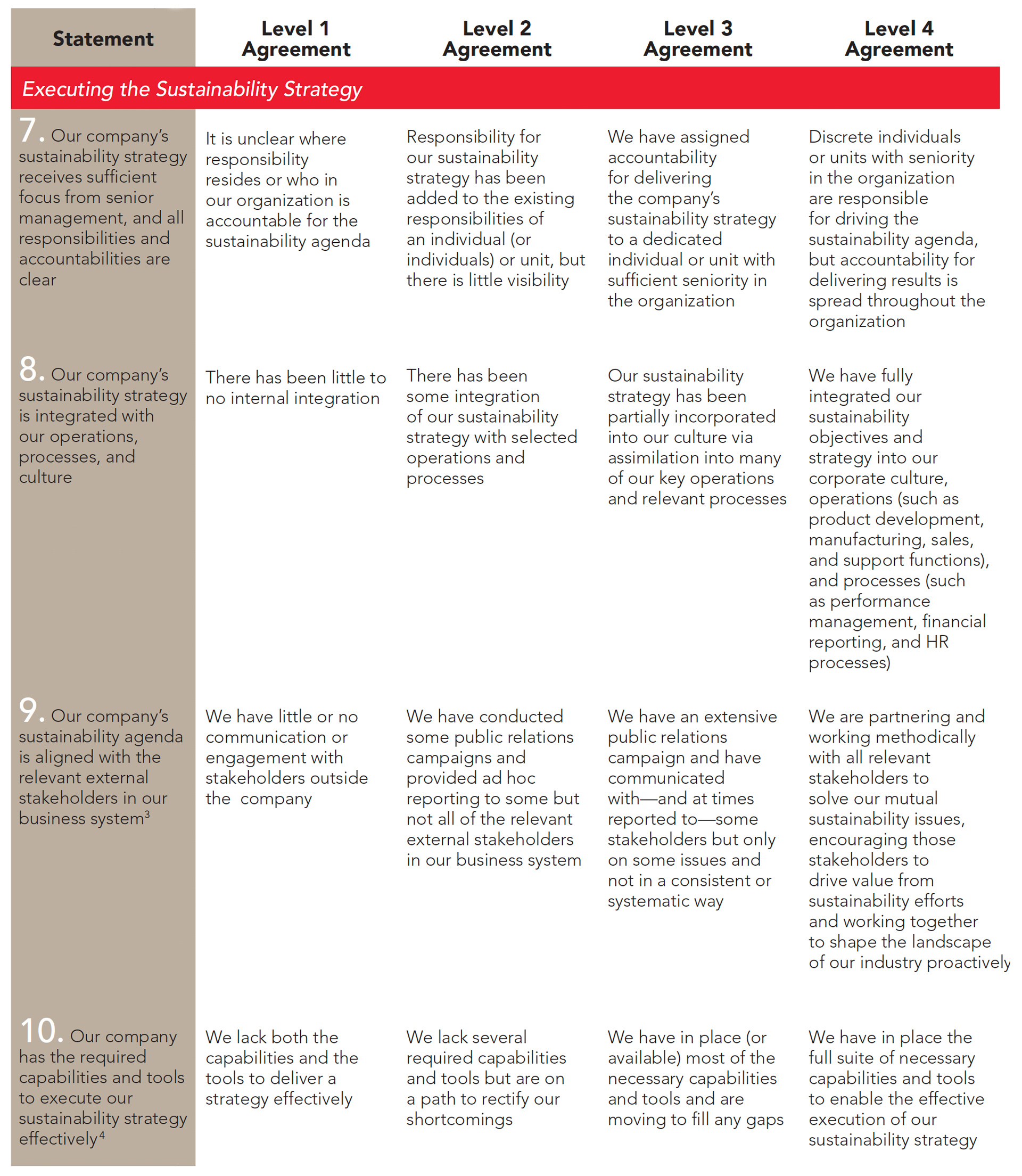

Companies that seek to enhance their profile in sustainability could begin by undertaking a critical self-assessment. This Sustainability Audit identifies 10 statements that we believe represent the most important dimensions of sustainability from a managerial perspective. These statements were developed by drawing on the lessons of organizations that boast first-class capabilities in sustainability. Those company executives who candidly evaluate their level of agreement with each statement in this audit will gain an understanding of where their organization stands and which areas it needs to focus on.

Footnotes

- Drivers include government legislation, pressure from consumers and customers, employee interest, pressure from society, the impact of ecological factors (for example, climate change, pollution, and the supply of resources such as food and water), and sociological factors (such as population growth, urbanization, and inequities in health and labor).

- Intangible impacts include enhanced brand awareness and equity (which leads to customer loyalty and the ability to command a price premium), improved employee recruitment, retention and engagement, and lower risk premiums (which improve calculations and enable easier access to capital and insurance).

- Stakeholders include consumers, business-to-business customers, competitors, regulators, nongovernmental organizations, society overall, financiers, lenders, and capital-market analysts.

- Capabilities and tools include but are not limited to frameworks for developing the business case; measurement, tracking, and reporting tools; scenario-planning capabilities; technologies for product design and manufacturing; supply chain technologies; capabilities in partnering with stakeholders; and regulatory expertise.

Lessons from First-Class Companies

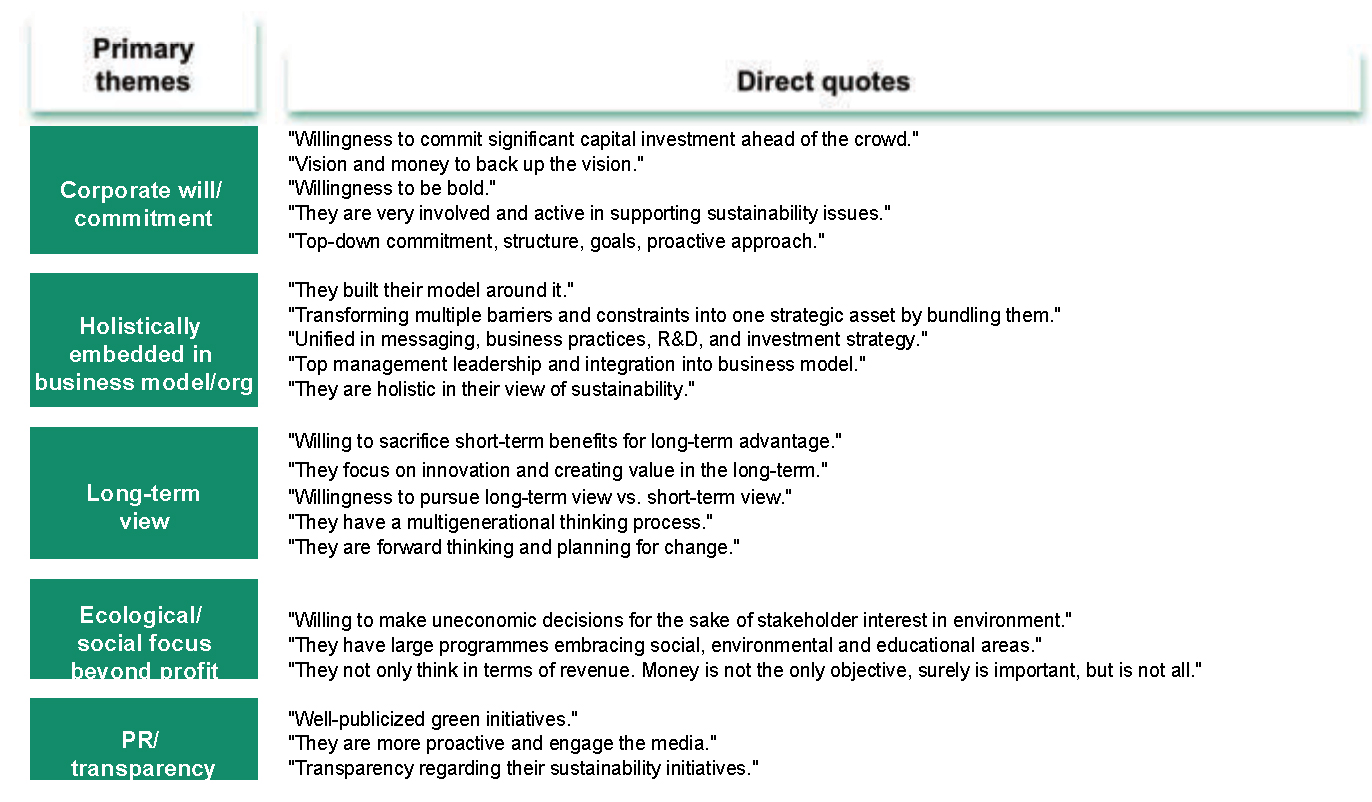

There is much that can be learned about how to overcome the managerial obstacles to sustainability by examining the companies that are leading the way and — even more important — creating value while doing so. We asked corporate executives in the broader survey group which companies they consider to have first-class capabilities in sustainability and why. We also gathered deep perspectives on these — and other — leading companies’ practices and key success factors through in-depth interviews with executives. (In The Sustainability Audit, we synthesize the lessons from leading companies into a tool that companies can use to assess their own progress.)

Rio Tinto: Mining the Social Dimensions of Its Vast Operations

Backstory: Given its business of mining over 5 million tons of rock a day, Rio Tinto has a big footprint. The mines are expensive, take decades to develop fully, and are not portable if something goes wrong. To reduce the political and economic risk and thus ensure steady returns, Rio Tinto has sought to win the backing of local communities, governments, and the society in which it operates.

Challenge: How does a company obtain a “social license” to operate, and nurture the local labor force that it needs?

Key moves: About a decade ago, Rio Tinto came up with the concept of working within communities on outreach and social and economic development. At the time, the company was developing a mine in Madagascar that was a source of contention with NGOs, which were worried about threats to biodiversity and the local community. Ninety percent of the island had already been cleared by farming, grazing, and charcoal production; the mine was situated on one of the island’s last pristine regions. The challenge was to create an operation “respectful to the environment, respectful of our employees, that is seen to be sustainable,” said CEO Tom Albanese.

A plan was developed to protect the environment and create economic opportunities in the communities surrounding the project, setting up standards and goals for the company to meet. These in turn aligned with broader company policies on environmental stewardship, social well-being, governance, and economic prosperity.

Putting this strategy to work, Rio Tinto created a long list of measures including:

- Policies to protect biodiversity and water quality around mine locations

- Employment for aboriginal peoples living near its mines

- Training programs to shift employees from manual labor into skilled positions

- Plans for the day mining would be done, seeking to prevent “ghost towns”

- Goals for greenhouse-gas emissions and energy use

Impact: Through these coordinated initiatives, Rio Tinto has obtained what it calls a “social license to operate.” The company felt an urgency, because it recognized a global brand risk if it operated without such a license. Rio Tinto also helped form the International Council on Mining & Metals, which encourages sustainable practices across the mining sector.

General Electric: An Opportunistic Push into Sustainable Business

Backstory: General Electric Co. decided sustainability was a business opportunity rather than a cost and pushed into the field in 2005 with its ecomagination initiative. But the products and services weren’t only for its customers—they first transformed GE.

Challenge: How do you create a new business in sustainability and move into the major leagues?

Key moves: General Electric began looking at sustainability as part of a demographic trend, realizing that scarcity would increase with population growth. Energy and water use, waste, carbon emissions—all would decline among the most efficient and sustainable companies. GE saw a profitable business opportunity in helping companies along this sustainable path. So it set up its ecomagination unit to offer environmental solutions.

GE also gambled that carbon would eventually be a cost, following the implementation of previous regulatory regimes such as limiting acid rain. Although the precise way carbon would be regulated was unknown, as it still is, the company had little doubt that regulation would come to pass. Rather than wait, GE joined a climate coalition with nongovernmental organizations to press for a cap-and-trade system to build certainty into the future.

Within the company, GE began engaging employees to see where energy savings could be found. That might be turning off the lights when a factory was idle, or even installing a switch so that lights could be turned off. Ecoimagination sold solutions within GE, whether the project involved installing LED lights on a factory floor, recycling water at a nuclear facility, or offering combined heat and power generation units at a plant in Australia. This wasn’t just lip service. Within GE, managers began to be measured on how much energy savings they had achieved.

Impact: The company so far has saved $100 million from these measures and cut its greenhouse-gas intensity—a measure of emissions against output—by 41 percent, according to the company’s sustainability report. The work inside GE became a proof of concept to external customers grappling with similar issues. Ecomagination targeted C-level executives to build this business, since most problems cut across divisions (improving energy effi ciency, for example). It was not about selling a product, but an approach, a mind-set, to improve business in a new carbon-constrained world. So far GE has invested $4 billion in this effort, much of it in research and development. But it reaped sales of $17 billion in 2008, up 21 percent from a year earlier and is striving for $25 billion in sales in 2010.

WAL-MART: Repurposing the Supply Chain

Backstory: Wal-Mart, the largest retailer in the world with over 7,800 stores, has been working steadily to improve sustainability. From installing green roofs to rolling out a more efficient trucking fleet, the company has moved forward internally, but now it is bringing its suppliers along.

Challenge: How do you green the supply chain?

Key moves: Wal-Mart has been pushing sustainability since adopting the strategy in 2005, establishing goals of being 100 percent fueled by renewable energy, producing zero waste, and selling products that will sustain the environment.

So how does that happen? In one famous example, it began working with Unilever plc in 2005 to sell concentrated laundry detergent in a 32-ounce container (equivalent to 100 ounces under a previous formulation). Consumers got a more powerful detergent in a smaller package. Three years after rollout, the container saved 80 million pounds of plastic resin, 430 million gallons of water, and 125 million pounds of cardboard, according to a company fact sheet.

More importantly, it became an industry standard, prompting other packaged goods companies to switch to concentrated detergent as well. Wal-Mart’s zero waste initiative is also moving forward. The company, which is aiming to eliminate all landfill waste by 2025, was able to reduce waste by 57 percent between 2008 and 2009. It did so by improving inventory management, increasing donations, and ramping up recycling (including 25 billion pounds of cardboard).

Now it is striving to push these criteria down into the supply chain, on a three-stage path. First, it wants to get suppliers to rate their products on sustainability criteria. Second, it wants to gather data on product life cycles; third, it is creating a sustainability index that will increase transparency for the consumer.

The first initiative, rolled out earlier this year, involves a questionnaire sent to more than 100,000 suppliers. It polls them on four categories: their energy and greenhouse-gas emissions, waste and quality initiatives, “responsibly sourced” materials, and ethical production. Products are also being measured through their life cycle. Collaborating with academics, retailers, NGOs, suppliers, and the government in a consortium, Wal-Mart’s goal is to build a global database of product information. As environmental consultant Joel Makower wrote on his blog, http://makower.typepad.com,“the consortium’s mandate is to focus on how to evaluate products, which Wal-Mart hopes will become the basis for standards, ratings, or other product-level evaluations that it would use in its stores.”

That data will be used to develop an index for consumers to evaluate products, though it’s still unclear how that information will be measured and presented. Nor is there a timeline for rolling such an index out.

Impact: Wal-Mart wants its sustainability index to be open to all, becoming a standard to measure and communicate the green credentials of a product and thus becoming “a tool for sustainable consumption.” In the process, the exercise of measurement itself may reap rewards in more efficient production, less waste, and lower emissions—all of which are also cost-savings measures.

While the particulars of each of these companies’ respective sustainability campaigns are unique, all first-class approaches have several key characteristics in common.

First-class companies understand and articulate sustainability’s impact on their organization. Leaders in sustainability gather the full set of facts and incorporate this knowledge into how they frame and define sustainability strategically and economically. They also adopt a systemwide view in understanding the relevant issues and needs of all their stakeholders. For example, they push suppliers to be better stewards of sustainability — often even selecting them on that basis. And they form partnerships and alliances with critical influencer groups (such as regulators, NGOs, experts, communities, and other companies) so that they can learn about and jointly develop innovative solutions. Mining firm Rio Tinto, for example, leads an industrywide initiative in sustainable development and has ties to the International Council on Mining and Metals. (See the Mini-Case, “Rio Tinto: Mining the Social Dimensions of Its Vast Operations.”)

They create a robust business case for sustainability. In developing the financial case for sustainability, first-class companies speak the language of business: value creation. They assess their sustainability strategies as they would any investment, systematically evaluating each value-creation lever — including the intangibles, which are more difficult to model.

These companies also make effective trade-offs between short-term expectations and longer-term impact, bringing the same long-term mind-set to sustainability investment decisions as they do to other routine long-term bets. They take into account in all external factors and system effects when analyzing the business case for sustainability, assessing the full set of costs and benefits.

Grounded in the facts and a solid business case, they publicly commit to ambitious goals that they measure and report — and they demonstrate that sustainability investments produce real business results.

“You cannot implement these kinds of programs bottom-up — it’s impossible. It’s always top-down, always. Because it’s such a cultural change, you cannot do it organically.”

Georges Kern, CEO, IWC

They holistically integrate their sustainability strategy throughout the business. First-class companies believe that sustainability is a source of value creation rather than merely a legal imperative. They therefore work to integrate it deeply into their culture and embed it holistically into their strategy and all relevant aspects of their operations, while supporting it through strong, top-down commitment from the executive leadership team.

In sum, the companies that are winning with their sustainability approaches are embracing aggressive strategies, adapting their organizations, and creating new sources of advantage to deliver measurable business results.

Peering over the Horizon

Sustainability will have an increasingly large impact on the business landscape going forward. Companies that recognize this fact and position themselves at the forefront stand to reap sizable competitive advantages. Consider the following emerging realities:

“The time to take risks is when you’re successful, not when you’re sliding down the slope.”

Tim Mohin, principal consultant, Environmental and Occupational Risk Management; former senior manager for supplier responsibility, Apple; former director of sustainable development, Intel

- Prices for food, water, energy, and other resources are growing increasingly volatile. Companies that have optimized their sustainability profile and practices will be less exposed to these swings — and more resilient.

- Stakeholders — including consumers, customers, shareholders, and the government — are paying more attention to sustainability and putting pressure on companies to act.

- Governments’ agendas increasingly advocate for sustainability. Companies that are proactively pursuing this goal will be less vulnerable to sudden regulatory changes. They will also be better positioned to have a voice in shaping policy — rather than simply reacting to it.

- Capital markets are paying more attention to sustainability and using it as a gauge to evaluate companies and make investment decisions.

- First movers are likely to gain a commanding lead, and it may become increasingly difficult for competitors to catch up.

The experiences of executives already wrestling with sustainability-driven business issues suggest that companies need not make large, immediate investments in new programs. The findings reveal instead that what is essential is that companies start to think more broadly and proactively about sustainability’s potential impact on their business and industry — and begin to plan and act.