Building an Effective Global Business Team

Every global company’s competitive advantage depends on its ability to coordinate critical resources and information that are spread across different geographical locations. Today there are myriad organizational mechanisms that global corporations can use to integrate dispersed operations. But the most effective tool is the global business team: a cross-border team of individuals of different nationalities, working in different cultures, businesses and functions, who come together to coordinate some aspect of the multinational operation on a global basis.

It is virtually impossible for a multinational corporation to exploit economies of global scale and scope, maximize the transfer of knowledge or cultivate a global mind-set without understanding and mastering the management of global business teams. That, however, is easier said than done. In our study of 70 such teams, we discovered that only 18% considered their performance “highly successful” and the remaining 82% fell short of their intended goals. In fact, fully one-third of the teams in our sample rated their performance as largely unsuccessful.1 How can companies reverse the weak performance of faltering global business teams? First, they must understand the obstacles to success that global business teams confront. Then they can take concrete steps to avoid those pitfalls and build effective and efficient teams.

Why Global Business Teams Fail

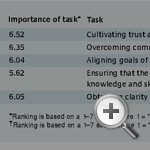

Domestic teams and global teams are plagued by many of the same problems — misalignment of individual team members’ goals, a dearth of the necessary knowledge and skills, and lack of clarity regarding team objectives, to name a few. But global business teams face additional challenges resulting from differences in geography, language and culture. Teams can fail when they are unable to cultivate trust among their members or when they cannot break down often-formidable communication barriers. The results of our survey of 58 senior executives from five U.S. and four European multinational organizations confirm that important, unique challenges confront global business teams — challenges that tend to exacerbate the more common problems all teams face. (See “The Challenge of Managing Global Business Teams.”)

The Challenge of Managing Global Business Teams

References

1. To date, no empirical study has presented data on the effectiveness of global business teams. A broad treatment of the international dimensions of organizational behavior, however, suggests that, although cross-cultural teams are necessary, the challenge of managing diversity often renders them ineffective. See Nancy Adler, “International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior” (Boston: Kent Publishing, 1986), 99–118.

2. D.J. McAllister, “Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust as the Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations,” Academy of Management Journal 38 (1995): 24–59.

3. R.M. Kramer and T.R. Tyler, eds., “Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research” (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1996).

4. H. Hofstede, “Motivation, Leadership and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad?” Organizational Dynamics 9 (summer 1980): 42–63. According to Hofstede, cultures can differ across four dimensions: power distance, the extent to which power is centralized; individualism/collectivism, the extent to which people view themselves as individuals as opposed to belonging to a larger entity; uncertainty avoidance, the difficulty people have in coping with uncertainty and ambiguity; and masculinity/feminism, the extent to which people value materialism as opposed to concern for others.

5. A. Tversky and D. Kahneman, “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice,” Science 211 (January 1981): 453–458.

6. K.G. Smith, K.A. Smith, J.D. Olian, D.P. O’Bannon and J.A. Scully, “Top Management Team Demography and Process: The Role of Social Integration and Communication,” Administrative Science Quarterly 17 (1994): 36–68.

7. K.M. Eisenhardt, J.L. Kahwajy and L.J. Bourgeois, “How Management Teams Can Have a Good Fight,” Harvard Business Review 17 (July–August 1997): 77–85.

8. Ibid.

9. M.N. Chaniu and H.J. Shapiro, “Dialectical and Devils’ Advocate Problem Solving,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management (May 1984): 159–168.

10. D.B. Stoppard, A. Donnellon and R.I. Nolan, “Verifone,” HBS case no. 9-398-030 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Corp., 1993).

11. John Pepper, chairman of the board, Procter & Gamble: remarks to an MBA class at the Tuck School, Dartmouth College, May 1995.

12. Ibid.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Readers interested in learning more about teams in general and global business teams in particular should note: D. Ancona and D. Caldwell’s 1992 article, “Demography and Design: Predictors of New Product Team Performance,” in Organization Science; K. Bantel and S. Jackson’s 1989 “Top Management and Innovations in Banking” in Strategic Management Journal; J.R. Hackman and associates’ 1990 book “Groups That Work and Groups That Don’t,” from Jossey-Bass; D. Hambrick, T. Cho and M.-J. Chen’s “The Influence of Top Management Team Heterogeneity on Firms’ Competitive Moves” from a 1996 Administrative Science Quarterly; L.H. Pelled, “Demographic Diversity, Conflict and Work Group Outcomes: An Intervening Process Theory,” in a 1996 Organization Science; S. Finkelstein and D. Hambrick’s 1996 Jossey-Bass book, “Strategic Leadership”; J.R. Katzenbach and D.K. Smith’s 1993 article in Harvard Business Review, “The Discipline of Teams”; and P.C. Earley and E. Mosakowski’s “Creating Hybrid Team Cultures: An Empirical Test of Transnational Team Functioning,” published last year in Academy of Management Journal.