The Art of Piloting New Initiatives

Multinational companies often test new or improved processes by rolling out a limited pilot in one or several markets. New research identifies how to maximize the chances of success for these high-stakes dress rehearsals.

Topics

At KONE Corp., the Finland-based elevator and escalator company, the United States is frequently used for piloting sales processes, but Finland is used for operations projects.

Image courtesy of KONE Corp.

Multinational companies are under more pressure than ever to maintain their competitive edge. One way they try to meet the challenge is by implementing global headquarter-driven strategic initiatives designed to leverage their global scale with new or improved processes. Such strategic initiatives as harmonizing sales processes, launching a new global service for customers, building a shared service processing center or introducing standardized operations processes can create economies of scale and scope in operations. Successful initiatives may also make it possible to compare process performance across locations, uncovering new opportunities.

To try to improve the chance of success for such initiatives,1 companies often conduct a field test of the global initiative in a restricted part of the business, such as a single country market or a small group of country markets. If this pilot succeeds in demonstrating the value of the new practice, top management will roll out the initiative regionally or globally to realize its full economic and strategic value.

Senior executives sometimes regard learning as the primary goal of piloting a global initiative. They assume that if anything does go seriously wrong, the stakeholders will be forgiving because the pilot is just an experiment. Our research, however, has found that the stakes are actually much higher. (See “About the Research.”) During the pilot, the country market managers next in line to implement the strategic initiative form their own attitudes about it. Their assessment of the pilot often determines the extent to which it will be eventually adopted within the organization. In this way, a pilot is much more like a dress rehearsal than an experiment. If the performance fails to impress the country managers, they are likely to adopt the initiative in a perfunctory way, without genuinely integrating the processes within the organization.2 Or if the pilot’s performance is truly terrible, managers from across the organization may band together and refuse to even start their implementation.

The Leading Question

What improves the odds of success when piloting a global strategic initiative?

Findings

- If the pilot performance fails to impress managers in other countries, they are likely to adopt the initiative in a perfunctory way.

- Successful pilot locations share three qualities: credibility, replicability and feasibility.

- Delegate decisions beyond your expertise, but retain oversight of them.

Fortunately, we have found in our research and our 20 years’ experience as corporate strategy and implementation researchers that it is possible to improve a pilot’s chances of success and therefore contribute to the value strategic initiatives add. If the venues of pilot projects are carefully chosen and executed, the managers in the locations following the pilot not only will be more willing to adopt the innovation but will actively push to be next in line for implementation.

Piloting in Multinational Companies

A pilot can be described as an evolving experiment with an attitude. Most pilots start with a theoretical prototype for a new working practice, but as soon as implementation gets underway, the original concept inevitably starts to be adapted to suit the realities of the pilot location, the convenience of the people who will use it and the need to integrate with other processes.

Typically, each pilot project is implemented by a cross-functional global team from corporate headquarters composed of functional experts, who formulate the new processes, and IT professionals, who embed these new organizational routines into IT systems. The global team, in consultation with several country subsidiaries, first designs the theoretical template or prototype for implementing the project. Then the team recommends a suitable pilot location where it can work with a local team to implement this theoretical template. As the team learns more, the template design typically morphs toward something more feasible to implement that can be replicated in additional locations. This means that the scope of a pilot may well evolve over time. It is only when the pilot shows that the practice is feasible, with the first signs that it is beneficial, that the global team rolls the working template out to the rest of the company.3

The most significant reason for employing a pilot as the first step in any initiative is to reduce the high levels of uncertainty associated with introducing any innovation4 and to protect the organization from the risk of expensive failure. Internal uncertainty comes from a lack of knowledge about whether the initiative is technically possible and whether the organization is ready to accept change. External uncertainty comes from not knowing how the market and customers will respond to the new practice. Conducting a pilot allows the global team to test whether the theoretical template makes sense and to check that the solution is stable. Knowledge gained during the pilot irons out any process wrinkles and ensures that employees within the subsidiaries come to grips with the new ways of working and master any system changes.5 Finally, the pilot is expected to “prove” the local business case for the initiative, which instills confidence that the global business case is achievable.

Our research shows that the way a pilot is selected and implemented can make or break a global initiative. Well-selected and well-conducted pilots create a strong commitment to change in the managers from the country subsidiaries next in line for implementation.6 Managers’ belief in the initiative translates into a willingness to sell the change within their own organizations and leads to full implementation of the initiative, including the committed use of the new business processes. However, if managers in the rollout countries are not convinced by the pilot, they may execute half-heartedly or even openly refuse to implement the initiative.

Successful pilots share three qualities:

Credibility. The pilot location must have the characteristics, skills and business coverage to legitimize the strategic initiative.

Replicability. The global team must create a template in the pilot that is rapidly transferable across locations and an effective transfer methodology.

Feasibility. The pilot must meet the expectations of multiple stakeholders in the organization.

In this article, we show how managers achieve a balance between these three factors during pilot selection and implementation.

Location, Location, Location

Massimo Beccarini, head of business solutions in the global development team of KONE Corp., the Finland-based elevator and escalator company, has learned from experience that stakeholders pay a great deal of attention to where an initiative is piloted. Over the last five years under the guidance of KONE CEO Matti Alahuhta,7 the global development team has been charged with deploying teams from corporate headquarters and business units to implement more than 50 business transformation initiatives. All of these employed pilots, and the majority have succeeded, a much higher than normal percentage. How did he do it? Beccarini attributes a large part of this success to selecting a credible pilot location.

Managers at KONE and other companies that are good at piloting look for a number of qualities in a pilot candidate, particularly the extent to which the pilot location has strong skills, expertise and experience in the functional dimensions that are important for the strategic initiative. This clearly signals to the organization that the global template created in the pilot has the potential to become best practice companywide and could build competence within their own subsidiary. We found that, in any given multinational, there are definitely “horses for courses” in pilot selection. For instance, at KONE, the United States is frequently used for piloting sales processes, but Finland is used for operations projects. At Tetra Pak International SA, a multinational food processing and packaging company based in Lausanne, Switzerland, finance projects are piloted in Europe, but Brazil or Mexico are used for operations projects. When rollout managers see the expert location being used for the pilot, they can say, “I’m confident in this initiative because I’m sure these people know what they are doing.”

When country markets have high unit sales, revenues, market share, profit or growth rates, this also provides a halo effect, and pilots are viewed more favorably.8 For instance, at KONE, France and Italy are seen as high-volume markets, while the Netherlands demonstrates high market share and rapid growth. All get the thumbs up as valid pilot locations. Part of the reason for this strong halo effect is that it is usually too early to judge the economic results of an initiative during the piloting phase, so managers partially base their perceptions of the initiative on the subsidiary’s overall reputation.

Pilot onlookers are sensitive to the degree to which the pilot location is similar to their own subsidiary. This phenomenon is similar to the principle of social proof, which suggests that in uncertain situations people tend to look at those most like themselves to determine what behavior to adopt.9 Many of the rollout managers we talked to took pains to explain how their country subsidiary was similar to or different from the pilot location. If the pilot was successfully conducted in a location broadly similar to their own, they were more positive about the initiative. For instance, a rollout manager in the United Kingdom for a Tetra Pak project to standardize purchasing processes declared that he had few reservations about the initiative because he had heard the pilot was going well in Italy, which had a similar arrangement to that in the United Kingdom, with the factory and market company colocated. This makes it important not to select a pilot that is atypical on key dimensions such as organizational structure, roles and responsibilities or systems. Intuitively, rollout managers can sense whether the template developed in the pilot is replicable in their own environment. One way to increase the perception of similarity to the pilot is to use multiple pilots. (See “Improving the Odds With Multiple Pilots.”)

If the pilot covers fewer business units, customer types or less complex products and services, then the working template may be viewed as too small and not credible by more complex operations. For instance, in one of the initiatives we investigated, Denmark was selected to pilot a new customer service but could only pilot with one major customer who used the service infrequently and for only one type of product. As a result, the pilot was widely disregarded by rollout managers, who complained bitterly that it did not actually demonstrate that the initiative could work in other locations. KONE’s Beccarini stresses that a pilot has to be meaningful in the context of the degree of business coverage of the rollout countries to avoid attracting this kind of criticism.

Two other elements also greatly improve chances of success. It may sound obvious, but the local management team in the pilot location should be 100% behind the initiative. Tepid support can doom a pilot. In one Asian pilot, an expatriate finance director volunteered the country market as the pilot, but without the buy-in of the rest of the local management team. As a result, the local employees actively resisted changing their ways of working, and the global team had an uphill battle to create enough commitment for others next in line to be willing to implement. This situation overstretched the global team, which was also struggling to fix the technical problems in the pilot.

Odds of success improve as well if the local organization has sufficient resources to implement the pilot. Beccarini estimates that the piloting phase takes twice as long as a typical rollout and consumes two to three times the staff and management time. Local managers must budget for that commitment. Last but not least, there should be a constructive working relationship between the global team and the local pilot team. Conducting a project under conditions of high uncertainty means that effective communication and coordination are essential to speedily resolve pilot issues. Often this chemistry develops through previous piloting experiences or during the construction of the theoretical template before the exact pilot location is chosen. Its absence may mean trouble.

But there is no perfect location. In selecting pilot locations, trade-offs must be made.

Credibility versus Feasibility From the above, one might think that global teams would always select large, high-profile countries with extensive business coverage as pilot locations. After all, if the initiative works there, it will work anywhere. But this is also highly risky, because a pilot in a high-profile country can lead to a high-profile failure. Size goes hand in hand with complexity, which can also jeopardize feasibility.10 Some companies are aware of this and plan accordingly. For instance, when Nestlé implemented its Global Business Excellence Program with the goal of creating a common set of “best practice” business processes to be used throughout the company, managers selected three pilot countries, one from each of the three main geographic regions. The managers selected countries that were large enough in terms of revenue to be credible but not so large that failure would compromise the financial results of the region.

Credibility versus Replicability High-profile country subsidiaries can sometimes act as “prima donnas,” insisting on many changes to the template. This may maximize the value of the initiative locally but destroy its replicability. Roger Delsen, a KONE change manager working in the Netherlands, described how a sales tool piloted in France had become so localized that the Dutch team had to hand it back to the global team and ask for it to be repiloted. In many companies we heard the refrain, “Don’t pilot in country X if you want to have a short and simple pilot. They will drag the project on forever until they get exactly what they want.”

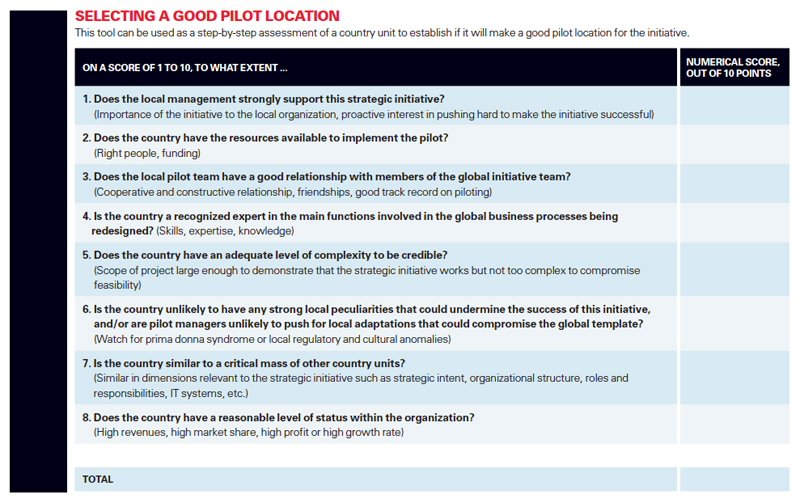

Replicability can also be compromised if the pilot location is strongly locally idiosyncratic. For instance, in one business transaction processing initiative, Thailand was selected, but during the pilot the global team discovered that it needed to make major adaptations to the theoretical template for local issues concerning tax, legal and special customer transactions. As a result, the template was both harder to implement for the duration of the pilot and more difficult to reproduce in the rollout. We have summarized these findings on pilot location selection into a tool that encourages global project leaders and teams to carefully assess whether a particular country location will make an effective pilot. (See “Selecting a Good Pilot Location.”)

Of course, picking the location of the pilot is only half the game. In the next section, we will discuss how credibility, replicability and feasibility play a role in creating a commitment to change during the implementation.

Setting the Objectives

Setting clear expectations at the start of a pilot enables the stakeholders to judge its feasibility and replicability. However, deciding how to set the expectations is not easy. While the goal of the overall initiative may be to increase sales, reduce costs or increase the efficiency of the assets, it is usually impossible to demonstrate the local business case for the initiative by the end of a few short months’ pilot. In addition, often the efficiencies of a strategic initiative only become visible after it has been implemented in multiple locations.

It also can be difficult to select meaningful key performance indicators and to set targets on these indicators because the global team is still learning about them during the pilot. For instance, one company implementing an initiative to create a regional shared service center started with a suite of key performance indicators that measured invoicing efficiency. However, during the pilot the company realized that it had missed a key indicator for measuring invoicing accuracy. The change was made, but not before managers realized that changing performance indicator definitions within the IT systems meant that the company would not be able to compare indicators before and after the pilot. The result was disagreement and confusion among senior management about whether or not the pilot had been successful and whether it could be replicated elsewhere.

Nevertheless, we found that the best project leaders did manage to set clear enough pilot objectives so that senior management could judge the feasibility and replicability of the initiative at the end of the pilot. As Beccarani told us, “If you don’t provide clear rules on what the expectations of this pilot should be and on what the deliverables are, you risk not being able to draw a clear conclusion or that the pilot will continue indefinitely.” Frequently, these objectives can be simple, such as focusing on the engagement levels of the employees adopting the new processes within the pilot. For instance, Alain Piguet, a KONE project leader working on a customer resource management initiative, measured the level of adoption of the new system by sales force personnel and their satisfaction levels. But rather than setting over-demanding targets, he simply demonstrated that these measures were steadily increasing over time.

Another good practice before starting a pilot is to make sure that the stakeholders agree on how the performance criteria will be measured. For instance, in an initiative to introduce a global design handling system, senior managers were divided over whether the pilot should be measured in terms of global cost reduction or increased customer satisfaction. Approval for the rollout was given based purely on the increased efficiency of the new operational processes, but the rollout managers in the other countries only grudgingly adopted the initiative because it did not meet their customer acceptance standards. After a year, the initiative had to be repiloted in a new location.

Finally, if there are no meaningful pilot performance indicators, senior managers frequently judge feasibility on whether the global team completed the pilot project plan on time and on budget. We found the use of these criteria to be highly problematic for the replicability of the pilot. Measuring success in this way tempts teams that are under time pressure to cut corners by not fully completing the global template. Problems in the pilot are then rolled out to other country markets, leading to a snowballing of issues that all need to be fixed simultaneously — a surefire way to stop an initiative in its tracks. Beccarini freely admits that senior managers at KONE have to become more critical in judging that the templates and implementation methodologies are complete and well-packaged before they decide to adopt the initiative and proceed with further implementation. Both KONE and Tetra Pak used a stage-gate approach to managing global business transformation initiatives similar to product development stage-gate processes.11 Tetra Pak used six stages — initiate, analyze, design, plan, develop and implement. Piloting is part of the development stage, after which senior management reviews the pilot results and makes a decision about the initiative before implementing the template across multiple locations. Stopping an initiative, however, occurs infrequently. If there are stubborn, hard-to fix problems, Tetra Pak repilots before rollout continues or shrinks the scope of the initiative.

Outrunning the Bear

Given that novel initiatives contain a high degree of uncertainty, global teams need to be prepared for the unexpected and commit sufficient resources in the pilot. This would not be so bad if project leaders could easily push back the pilot completion date, but the typical pilot runs for a predefined duration with a more or less defined budget. Learning and adapting to that improved understanding must happen right away. We like to describe this process as “outrunning the bear.” During any pilot, the size of the “bear” is dictated by the extent of unpleasant project surprises, scope changes, technical problems and change management issues. The global team and local pilot team together have to figure out how to learn fast enough to outrun the bear for the duration of the pilot. Fast learning requires strong local commitment to the pilot and the right learning culture.

It is important to select a pilot organization in which people in the ranks are not afraid to speak out and provide honest and open feedback. Pilots require people who are naturally curious and an environment that provides psychological safety so that team members do not feel that they will be punished for failure.12 Fast organizational decision-making processes are also critical, so that learning rapidly leads to changes in the pilot and the template can pass through multiple iterations. Coordinated learning in the global and local pilot teams needs to be front-loaded during the early phases of the pilot and explicitly scheduled into regular meetings.

Tetra Pak International, a multinational food processing and packaging company, used six stages for managing global business transformation initiatives: initiate, analyze, design, plan, develop and implement.

Image courtesy of Tetra Pak.

Given that it is never clear at the start of a pilot how large the bear might be, it makes sense for project leaders to plan for the worst and hope for the best. One of the most experienced project leaders that we talked to at Tetra Pak emphasized that during a global standardization initiative, he was careful to allow a wide margin in terms of pilot duration and budget. In the end, through good planning and some luck, the bear might stay relatively small but, as he said, it was much better to come in under time and under budget with a completed and replicable global template than to do the opposite.

Some global teams are so busy putting out technical fires that they forget to assist the local management team with change management. But making sure that employees who are changing their ways of working support the initiative is critical to persuading managers in the rollout that the initiative is worth adopting. For instance, when Nestlé launched its Global Business Excellence Program, a global implementation of its business excellence initiatives and standardization of working practices supported by SAP, the global team developed an extensive template solution with training that allowed knowledge gained in past implementations to be captured for future rollouts. This ensured the replicability of the tested template and provided a methodology for implementation. The methodology consisted of seven phases, with work packages around themes that allow for effective implementation and support before, during and after implementation. These methodologies that create commitment are also an essential part of the rollout of the global template.

The Importance of Communication

In any initiative, performance feedback from the pilot spreads rapidly through informal networks with a strikingly high degree of accuracy. We found that potential rollout managers actively seek out news from friends and colleagues in the pilots and that this often creates an initiative “buzz.”13 What lessons should global managers draw from this information?

Covering up bad news is always counterproductive. In one initiative where the pilot was not going according to plan, the global team tried to reassure people by communicating that everything was on track. One of the pilot managers working in the local team said he felt that the global team was trying not to make the initiative sound difficult because they didn’t want everybody to get discouraged, but it didn’t work. “Everybody wanted to know how it was going; the informal networks were hopping,” he recalled. “Now, people can read between the lines too. When you talk to your colleagues and can’t get straight answers, people find out what’s really happening. You know nobody is fooled by the global press.”

If some aspects of the pilot are not going well, it is better to be transparent, admit them and explain how you will fix them rather than pretend that they don’t exist. According to Beccarini, global team leaders at KONE learned this lesson the hard way at the start of the globalization process, and all project leaders are now keenly aware of the need to be transparent. In extreme cases, if the pilot is going disastrously it may be much wiser to simply stop, redesign the theoretical template and then repilot in a new location rather than struggle on with a poorly designed pilot that is generating widespread bad press. Steering members need to be sensitive to when the negative buzz around an initiative has reached such a level that they need to intervene.

Good news helps speed adoption. A positive buzz through informal networks supports the success flywheel and builds execution momentum. Here the global team needs to provide platforms for the pilot managers to talk about their positive experiences. At KONE, Simon Green, the project leader of an initiative to launch a global company Web presence, used an e-business conference to showcase pilots in the United States, France and Finland. Listening to the pilot managers gave rollout managers the confidence that they could implement the initiative successfully and also provided them with a list of implementation dos and don’ts. When global teams can showcase positive results from pilots, commitment becomes contagious.

In general, communication about the project must be open from the start. Before beginning the pilot, realistic objectives must be set. Once implementation is underway, fast learning and honest communication are essential parts of the process. Finally, global steering members governing the introduction of new global practices through the various stages of implementation need to listen to both positive and negative feedback from the pilot — and be honest enough to assess whether the global template and associated implementation methodology are truly ready for rollout.

References

1. A McKinsey Global Survey estimated that only 38% of transformations are completely successful at improving organizational performance. See “Organizing for Successful Change Management: A McKinsey Global Survey,” McKinsey Quarterly (July 2006).

2. See T. Kostova and K. Roth, “Adoption of an Organizational Practice by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects,” Academy of Management Journal 45, no. 1 (February 2002): 215-233.

3. While S.G. Winter and G. Szulanski focus on replication of existing practices, piloting addresses the creation of working templates for new practices that are then replicated. See S.G. Winter and G. Szulanski, “Replication as Strategy,” Organization Science 12, no. 6 (November/December 2001): 730-743.

4. A. De Meyer, C.H. Loch and M.T. Pich, “Managing Project Uncertainty: From Variation to Chaos,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 2 (winter 2002): 60-67. 5. J. Cantwell and R. Mudambi, “MNE Competence-Creating Subsidiary Mandates,” Strategic Management Journal 26, no. 12 (December 2005): 1109-1128.

6. For measurements of commitment to change, see L. Herscovitch and J.P. Meyer, “Commitment to Organizational Change: Extension of a Three-Component Model,” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, no. 3 (June 2002): 474-487.

7. See R. Milne, “Lift Maker’s Ascent to the Next Level,” Financial Times, Sept. 27, 2009.

8. See P. Rosenzweig, “The Halo Effect … and the Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers” (New York: Free Press, 2007).

9. See R.B. Cialdini, “Influence: Science and Practice,” 4th ed. (Needham Heights, Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon, 2001).

10. An exception to this is if the new ways of working have to be encapsulated in a system where it is impossible to extend the functionality of the system at a later date, in which case the pilot has to be selected for maximum complexity.

11. R.G. Cooper, “Stage-Gate Systems: A New Tool for Managing New Products,” Business Horizons 33, no. 3 (1990): 44-54.

12. See A. Edmondson, “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 2 (June 1999): 350-383.

13. See X. Gilbert, B. Büchel and R. Davidson, “Smarter Execution: Seven Steps for Getting Results” (London: Financial Times/Prentice Hall, 2008).