Automated Decision Making Comes of Age

After decades of anticipation, the promise of automated decision-making systems is finally becoming a reality in a variety of industries.

For decades, futurists have anticipated the day when computers would relieve managers and professionals of the need to make certain types of decisions.1 Computer programs would analyze data and make sound judgments on such matters as how to configure a complex computer, how to diagnose and treat a patient’s illness or how to know when to stir a big vat of soup with little or no human help. But automated decision making has been slow to materialize. Many early artificial intelligence applications were just solutions looking for problems, contributing little to improved organizational performance.2 In medicine, for example, doctors showed little interest in having machines diagnose their patients’ diseases. In the business sector, even when expert systems were directed at real issues, extracting the right kind of specialized knowledge from seasoned decision makers and maintaining it over time proved to be more difficult than anticipated.

Airlines use automated decision-making applications to set pricing based on seat availability and the hour or day of purchase.

Image courtesy of Flickr user kevin dooley.

Even though the need for automated decision systems was recognized, full-blown decision-making systems were seen as impractical for use in business. So, during the 1970s, managers began to address this need by employing intelligence augmentation tools that provided managers and analysts with “decision support.”3 The idea was for the support system to help managers report, analyze and interpret data as opposed to actually making the business decisions. Although some decision support tools offered the potential for sophisticated statistical insight into business problems, they generally required skilled users to direct their use. The tools were usually not integrated with business applications. As a result, managers used them to help make decisions and then, if computers could help, used separate applications to carry out the decisions. For these and other reasons, such tools didn’t catch on — not nearly to the extent that more transactional software applications, such as enterprise resource-planning systems, did.

The reluctance on the part of executives to embrace decision-support tools during the 1970s and 1980s was not surprising. Just as doctors didn’t want to hand off the job of diagnosing their patients, executives were fundamentally wary of the notion that complex management decisions could be reduced to a set of rules or variables. In addition, many decision-support systems are complicated to use and difficult to maintain. Because few people in organizations could be sufficiently trained to use the systems, their use was limited to highly quantitative areas such as measuring the effectiveness of promotion pricing.

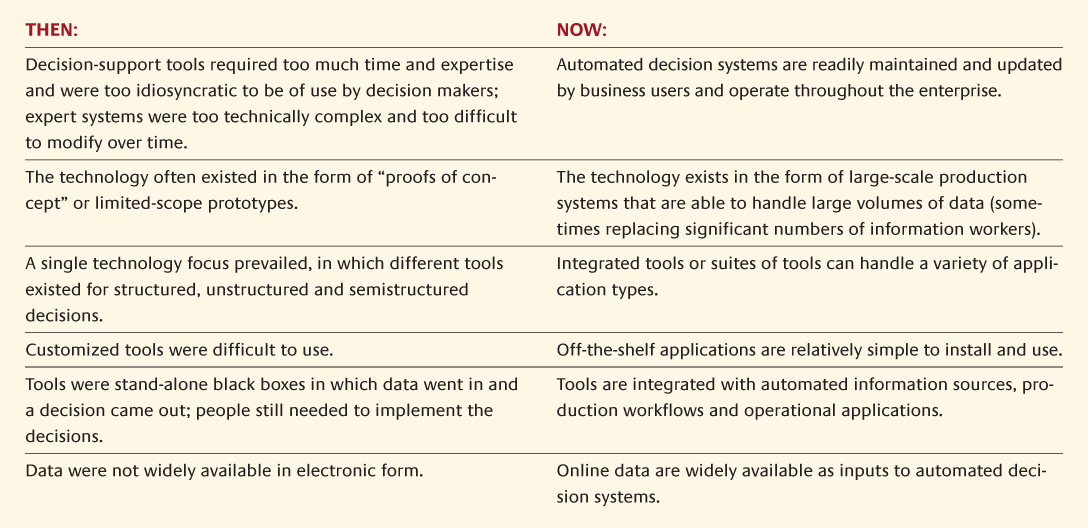

Despite these earlier obstacles, automated decision making is finally coming of age. The new generation of applications, however, differs from prior decision-support systems in several important respects. To begin with, the new systems are easier to create and manage than earlier ones, which leaned heavily on the expertise of knowledge engineers. What’s more, the new applications do not require anyone to identify the problems or to initiate the analysis. Indeed, decision-making capabilities are embedded into the normal flow of work, and they are typically triggered without human intervention: They sense online data or conditions, apply codified knowledge or logic and make decisions — all with minimal amounts of human intervention. And finally, unlike earlier systems, the new ones are configured to translate decisions into action quickly, accurately and efficiently. (See “Automated Decision Technologies.”) This is not to suggest that there is no role for people. Managers still need to be involved in reviewing and confirming decisions and, in exceptional cases, in making the actual decisions. Also, even the most automated systems rely on experts and managers to create and maintain rules and monitor the results.

Why Automated Decisions Now?

Why Automated Decisions Now?

Decision technology, artificial intelligence, data mining and the like have been talked about for so many years that many people are confused about where the basic ideas stand in terms of implementation. Some people believe that many of the applications have already been widely adopted by businesses for many years. Others think that most businesses have simply given up on adopting automated tools for decision making. Neither view is true. Instead, a convergence of forces and events is under way, making it an opportune time for companies to rethink how they make some of their most important decisions.

New interest in automated decision-making systems is being fed not only by changes in technology but also by evolving business needs. (See “Why Automated Decisions Now?”) Today’s applications can help businesses generate decisions that are more consistent than those made by people, and they can help managers move quickly from insight to decision to action. Moreover, they can potentially help companies reduce labor costs, leverage scarce expertise, improve quality, enforce policies and respond more quickly to customers.

As automating more decisions becomes possible, it is increasingly important for executives, knowledge workers and organizations to think about which decisions have to be made by people and which can be computerized. How companies respond will influence how successful they are at leveraging information workers and will, in turn, shape the future performance of their organizations.

Applying Automated Decision Making

Today’s automated decision systems are best suited for decisions that must be made frequently and rapidly, using information that is available electronically. The knowledge and decision criteria used in these systems need to be highly structured, and the factors that must be taken into account must be well understood. If experts can readily codify the decision rules and if high-quality data are available, the conditions are ripe for automating the decision.4 Bank credit decisions are a good example: They are repetitive, susceptible to uniform criteria and can be made by drawing on the vast supply of consumer credit data that are available. A decision about whom to hire as CEO, by contrast, would be a poor choice. It occurs only rarely, and different observers are apt to apply their own criteria, such as personal chemistry, which cannot be easily captured in a computer model.

Still, there are some types of decisions that, although infrequently made, lend themselves well to automation — particularly cases where decision speed is crucial. For example, in the electrical energy grid, quick and accurate shut-off decisions on the regional level are essential to averting a system wide failure. The value of this rapid response capability was clearly demonstrated during the summer of 2003, when automated systems in some regions of the United States were able to respond quickly to power surges to their networks by shutting off or redirecting power to neighboring lines with spare capacity. It is also evident in some of today’s most advanced emergency response systems, which can quickly decide how to coordinate victims, ambulances and emergency rooms across a city in the event of a major disaster.

By studying automated decision-making systems in industries that include banking, insurance, travel and transportation, we have found that automated decision applications are being used effectively to generate useful solutions in a number of different business areas. (See “About the Research.”)

Solution Configuration One of the earliest applications of automated decision technologies was product configuration (for example, allowing customers to specify exactly which features they wanted to have built into their new computer). Increasingly, this approach is being used in services. The most successful automated programs don’t produce a simple solution; rather, they select the best or most appropriate solution based on a set of variables (rules, data and complex relationships) that can be difficult to reconcile manually. A cellular phone operator, for example, may have a dozen different service plans; the role of the automated program is to find the one that’s appropriate for the specific customer. The system has the ability to weigh a variety of customer attributes in real time (including the customer’s online credit history) and present an offer during a call or Web session that can result in profitability for the company and satisfaction for the customer.

Yield Optimization For years, the airlines have used automated decision-making applications to set pricing based on seat availability and the hour or day of purchase. The most sophisticated yield-management systems can incorporate other factors, such as customer loyalty and lifetime value, into their decisions. Likewise, manufacturing, logistics and transportation companies, such as United Parcel Service of America Inc., have adopted their own applications to improve their operating efficiency. Increasingly, managers in industries that include retailing, entertainment and rental housing are experimenting with variable-pricing models in an effort to optimize their financial performance.

Routing or Segmentation Decisions Some companies have been able to achieve significant productivity improvements by designing automated filters for sorting cases or transactions. For example, in response to service backlogs, an insurance company established “priority lanes” (much like a grocery store) to handle the most straightforward insurance claims and those of regular customers with good profiles (even when some information is missing). Based on this approach, the firm increased its “no touch” rate (cases it can resolve without person-to-person contact) by 10%. Hospitals take advantage of similar systems in managing the volume and diversity of patients in emergency rooms.

Corporate and Regulatory Compliance Many routine policy decisions, such as determining whether someone qualifies for insurance benefits, are time-consuming and technical (even if the decisions themselves are not inherently difficult to make). Nevertheless, it’s essential that the rules be applied consistently. In the home mortgage industry in the United States, this is especially important. Lenders need to be able to identify and process loans that conform to the requirements of the secondary market, and if they are able to accomplish this efficiently they save on cost.

Fraud Detection Credit card companies and government agencies, such as the Internal Revenue Service and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, employ some level of automated screening to identify fraud. As new regulatory requirements come into effect in the United States, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Basel II capital accord for banking, more and more companies are likely to seek out improved systems for detecting possible fraud.

Dynamic Forecasting In recent years, manufacturers have increasingly assumed responsibility for maintaining inventory levels for their customers. Despite the potential operating advantages, it places manufacturers at significant risk. By further automating demand forecasting, companies are able to align their customers’ forecasts more closely with their own manufacturing and sales plans.

Operational Control Some automated decision systems are programmed to sense changes in the physical environment (for example, the power supply, temperature or rainfall) and respond rapidly on the basis of rules or algorithms. The systems designed to circumvent power outages, as noted in the 2003 example above, would fall into this category. But there are many more, including advanced systems used by farmers, which can monitor agricultural growing conditions and take appropriate action.

Developing Industry Applications

The transportation industry was one of the first to employ automated decision making on a large scale.5 After being used initially by airlines to optimize seat pricing, decision-making technology has since been applied to a variety of areas, including flight scheduling and crew and airport staff scheduling. Yield-management programs have also been adopted in related businesses, such as lodging. For example, Harrah’s Entertainment Inc., the world’s largest casino operator, makes several million dollars a month in incremental revenue by optimizing room rates at its hotels and by offering different rates to members of its loyalty program based on projected demand. The use of yield-management systems for hotel room pricing is common, but combining it with loyalty management programs is unusual. The combination ensures that the best customers get the best prices and, in turn, these customers will reward the company with their loyalty.

Among the other early adopters have been investment firms, which have relied upon decision-making technology extensively for program trading and arbitrage. Although these applications continue to be used, much of the recent activity within the financial industry has revolved around creating new applications aimed at finding good banking and insurance customers and serving their needs. The widespread availability of online credit information and financial history, the need for differentiation through rapid customer service and the rapid growth of online financial services providers have led to increases in automated decisions. In banking, real-time mortgage and secured lending decisions are becoming common.6 For example, Lending-Tree, based in Charlotte, North Carolina, uses automated decision making for two purposes: to decide which of its participating banks is most likely to issue a mortgage to a customer; and to offer the customer mortgage deals within a few minutes, using either the banks’ technologies or its own.

As intermediaries such as LendingTree become more widely accepted, lenders are forced to be more highly automated and are implementing automated decision engines to help them remain competitive. Consider the rapid development of DeepGreen Financial in Cleveland, Ohio, which was created from the ground up to make use of automated decision technology. DeepGreen originates loans in 46 states through its Web site and through partnerships with LendingTree, priceline.com and MortgageIT. com, based in New York City. It also offers home equity lending services for mortgage brokers and private-label or cobranded home equity lending technology and fulfillment services. Since its inception in 2000, DeepGreen’s Internet technology has been used to process more than 325,000 applications and originate more than $4.4 billion of home equity lines of credit, according to Jerry Selitto, the bank’s founding chief executive officer.

DeepGreen created an Internet-based system that makes credit decisions within minutes by skimming off the customers with the best credit, enabling just eight employees to process some 400 applications a day. Instead of competing on the basis of interest rates, DeepGreen’s drawing card is ease of application and speedy approval. The company provides nearly instantaneous, unconditional decisions without requiring traditional appraisals or upfront paperwork from borrowers. Customers can complete the application within five minutes, at which point the automated process begins: A credit report is pulled, the credit is scored, a property valuation is completed using online data, confirmations are made concerning fraud and flood insurance and a final decision is made on the loan. In about 80% of the cases, customers receive a final decision within two minutes. (In some cases, DeepGreen is only able to offer a conditional commitment because some of the information — usually the valuation — is not available online.) After approval, the system selects a notary public located near the customer’s home and the customer chooses a closing date. All the loan documents are automatically generated and express-mailed to the notary.7

DeepGreen’s competitive strategy is driven by the convergence of several factors. At its core, it relies on the advancement of analytic and rule-based technologies without which the business would not be possible. It also leverages the bank’s deep understanding of changing market conditions and pricing dynamics. Together with DeepGreen’s extensive use of online information, these factors enable the company to tailor loan terms to the needs of individual borrowers. Moreover, the company’s focus on high-end customers makes it possible to offer speed, service and convenience. Credit decisions involving affluent, low-risk borrowers are relatively easy to make. Finally, high-end borrowers tend to be Internet-savvy; if you build an online service that meets their specific needs, they will come.

The insurance industry is making extensive use of automated decision making as well, allowing underwriters to save significantly on cost.8 The use of rule-based technology in underwriting has become pervasive in large insurers’ “personal lines” businesses (such as homeowners and auto insurance), but it is also penetrating the more complex processes of small-business underwriting.

Insurance underwriting is both risky and expensive. By making too many bets, an insurance company can go bankrupt. An automated system can help insurance companies to increase consistency and leverage the abilities of their best underwriters. After the initial investment, automation can also save money, either by reducing the number of nonexpert underwriters required or by allowing the company to underwrite more business without adding employees.

Insurance companies are also looking to increase both the speed and flexibility of their underwriting processes. Customers who receive quick approvals are far less likely to seek insurance elsewhere. What’s more, automated decision-making systems can provide insurance companies with the ongoing capability to adjust their underwriting criteria whenever they choose in response to market opportunities. At any time, they can pursue the most profitable policies and customers. Competitors who lack automated decision-making capabilities are limited in their ability to revamp their products. They may be able to compete on speed but not on flexibility.

More sophisticated implementations involve the optimization of decision rules over time by skilled actuaries. For example, when underwriting rule definitions are combined with policy, loss and premium data in a data warehouse, actuaries can assess profitability and loss history by line of business, market segment or individual rule.

Although automated decision making is being used largely in industries where extensive quantitative analysis is required, it is also appearing in less predictable areas. Pickberry Vineyard, a winery in northern California, uses a network of remote sensors to monitor temperature, moisture, rain levels and other weather and soil conditions throughout its vineyards. Based on the data that the sensors generate, the vineyard has been able to automate some important decisions, including watering protocols. As useful as the decision-making system has become, management still retains control over critical decisions affecting the grapes. When the temperature drops during the cooler months, for example, someone still decides the old-fashioned way when to take protective measures.9

Even when fully automating a decision process is possible, fiduciary, legal or ethical issues may still require a responsible person to play an active role. In the healthcare industry, for example, many companies and institutions are exploring automated care protocols or intelligent order-entry systems that recommend a particular drug or course of treatment for a patient. In every case we know of, however, these systems augment but do not replace the judgments or decisions of physicians and nurses. A physician either initiates an order (and the system checks it) or the physician has the opportunity to override the recommendation of an automated protocol. Patients are safer when an automated system is combined with physician knowledge. At Partners HealthCare, in Boston, prescribing errors declined by 55% as a result of the adoption of an order-entry system that combined the two.10 Similarly, a major bank that tailors credit card offers to individuals based on their credit and payment histories relies heavily on a human analyst to review the offers before they are issued. Executives believe that effective offers need to combine good marketing with analytical science.

Emerging Management Challenges

Although automated decision technologies can help companies perform routine tasks more efficiently, they can also introduce a variety of managerial challenges. No matter how much certain decisions can be automated, managers still have the responsibility for defining the context and limits for automated decision making. This requires constantly monitoring applications to ensure that the boundaries and risk levels embedded within them are clearly understood. The consequences of not defining limits can be huge. Several years ago, during the e-commerce boom, Cisco Systems Inc., based in San Jose, California, belatedly found out that it was relying too heavily on its automated ordering and supply chain systems. Management realized that many of the orders that had been entered on the books were not as firm as they assumed and, in all likelihood, would never be shipped. This glitch eventually forced Cisco to write off more than $2 billion in excess inventory.

Over and above the close monitoring of risk levels, managers in charge of automated decision systems must also develop robust processes for managing exceptions. Among other things, they need to determine in advance what happens when the computer has too little data on which to make a decision (a frequent reason for allowing exceptions). Several organizations in our study said they wanted to eliminate exceptions altogether — and some had achieved automated levels of more than 95%. But the average level of automated processing was closer to 80% (leaving about 20% of the decisions in the hands of individuals). Companies should have clear criteria for determining when cases cannot be addressed through automation and who should deal with the exceptions. They should also ensure that exceptions are viewed internally as opportunities to learn, rather than as failures of the system. At some hospitals, for example, managers are quick to punish physicians and nurses for overriding automated decision systems. Instead, managers should attempt to understand the reasons for these actions.

One of the greatest challenges with automated decision systems is finding the experts who are capable of running them. Experts are necessary not only for designing the systems (many projects require several full-time experts for extended periods), but also for the ongoing analysis required to maintain and improve them.11 Recently, a midsize insurance company had to stop using its small-business insurance decision system for some of its policy lines because it didn’t have the underwriting experts or actuaries on staff to oversee the project properly.

New systems can also have significant impacts on staffing requirements, particularly for less skilled and less experienced employees. Although we heard of only one company (in the mortgage banking industry) that had engaged in major layoffs following the implementation of its automated systems, the reality is that there is little need for low-skilled or entry-level employees once automated programs are in place. To prepare their organizations for change, managers need to communicate as early as possible the types of decision making that will be automated and centralized, the kinds of decisions employees will continue to make and how the employment picture is likely to shift.

Because automated decision systems can lead to the reduction of large staffs of information workers to just a handful of experts, management must focus on keeping the right people — those with the highest possible skills and effectiveness. The employees who stay should have a highly refined understanding of the processes that are being automated and their relationship to the ongoing success of the business. Their judgment — from years of experience working on similar problems — will allow them to deal with the exceptions. They will need to monitor changing business conditions and act decisively to adapt rules for the benefit of the business.

Difficult as it is to find experts today to oversee some of the new systems, it is also by no means clear where companies will be able to find tomorrow’s experts. As the ranks of employees in lower-level jobs get thinner, companies may find it increasingly difficult to find people with the right kinds of skill and experience to create and maintain the next wave of automated decision systems. None of the people we surveyed had used their automated decision systems long enough to face this problem, but several anticipated that the issue was likely to arise when their internally trained experts retired or left for other companies.12

Legal and ethical concerns may also circumscribe the expanded use of automated decision technologies. On the day we interviewed a hospital manager for this study, for example, she was subpoenaed to appear in court to discuss her organization’s computer system in a malpractice case. There is a significant likelihood that more and more companies will be affected by lawsuits challenging automated decision methods. In the United Kingdom, individuals already have the explicit right to request that a decision affecting them not be made based solely on the automated processing of personal data.

Legislation mandating barriers to the integration of information about individuals may also limit the usefulness of automated applications. In countries where such laws are on the books, companies may find themselves at a considerable competitive disadvantage. Conversely, there may be countervailing pressures from regulators encouraging companies to standardize and document their decision-making processes as a way to ensure compliance.

A final issue for many organizations is how to reach consensus on rules. Although this can be relatively straightforward in operational environments such as insurance underwriting, getting agreement on rules in areas such as health care can be the basis of long and passionate debate. At one hospital, for example, some senior physicians were accustomed to having their own sets of rules. Because of their stature, they were not required to adhere to the rules that other doctors had to follow. This type of tension goes beyond small groups. Indeed, it is not uncommon for professional associations (such as those representing doctors or accountants) to balk at any new technologies that reduce the level of control that members have over service provision.

Looking Toward the Future

The widespread availability of data in many industries is hastening the move to automated decision-making systems. The more data that exist, the greater the potential there is for automation. New decision-making applications will continue to proliferate and will have substantial implications for organizations and the people who work in them.

There will be many opportunities in the future for experts who can work with computers, but ironically, there may be fewer and fewer avenues for becoming an expert. Organizations, therefore, will need to think carefully about the number and types of human decision makers they need and begin to develop them now. As automated decision making moves further and further up the organizational hierarchy, decision support will give way to decision automation in many areas. To the extent that prepackaged decision-oriented applications become increasingly available, companies will no longer need to develop their own proprietary systems. In some ways, though, this may make it more difficult for companies to differentiate themselves from competitors.

This brave new world of automated decision making has been a long time in coming, but it is now upon us. Businesses need to find ways to incorporate it into their strategies and processes or they may be left behind and lose their competitive advantage.

References (12)

1. For example, scientist and fiction writer I. Asimov’s “I, Robot” (New York: Gnome Press, 1950) identified the Three Laws of Robotics, an early set of rules to guide automated decision making. R. Kurzweil’s “Age of Intelligent Machines” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1990) contains an overview of the history of artificial intelligence.

2. T.G. Gill, “Early Expert Systems: Where Are They Now?” MIS Quarterly 19, no. 1 (March 1995): 51–81.