Strategic Choices in Converging Industries

As industries converge and seemingly unrelated businesses suddenly become rivals, managers must understand the new challenges and the long-term implications.

In the relentless evolution of technology and markets, many industries are in the midst of, or are approaching, major reconfigurations of their fundamental architectures and the way companies capture value.1 The changes are well underway in biopharma, nutrition products, health care and energy, where technologies and distinct knowledge bases are changing and converging. Perhaps the most dramatic example of such convergence is taking place in the booming space of telecommunications, information technology, media and entertainment, which many people now refer to as a single field, the “TIME” industries.2 The TIME industries are characterized not only by the variety of new technological products and services being launched at an ever-increasing pace but also by the surging complexity of their markets and how companies win. As some companies have expanded their scope, others have been forced to rethink and retool their strategies. In many ways, the TIME example offers a useful model for managers in other industries where convergence is less obvious. (See “Is Convergence Happening in Your Industry?”)

The amount of change that the telecommunications and related industries have seen in recent years has been extraordinary. Back in 2001, then-Nokia chairman Jorma Ollila said that “the mobile Internet should remain ‘under the control of the mobile industry, and not the computer makers.’”3 But that vision disintegrated when Internet browsing became mobile. Ericsson and Siemens, once market leaders, have disappeared from the mobile handset market. Other companies, such as Apple, Google and Samsung, have increasingly dominated the smartphone marketplace and appear to be shaping the future. (See “A Changing Landscape in Mobile Handsets.”)

While the changes have opened up new business opportunities for some companies, they have proved harmful to others. For example, Nokia’s brand has suffered, while BlackBerry is struggling to compete against the technical and financial power of giants such as Apple and Google. Despite its early promise, AOL Time Warner was not able to leverage the expected synergies at the intersection of Internet and media content.

With convergence, companies that were in seemingly unrelated businesses can become rivals. Indeed, the day the mobile phone industry seized upon a new way to design the user interface — beginning with Apple’s iOS, followed by Google’s Android — everything else became outdated. Consumers preferred ecosystems based on market-driven “apps” over services designed by the telecom carriers. Players such as Nokia were caught in the changing current. In September 2013, Microsoft announced that it will acquire Nokia’s devices and services business.

Is Convergence Happening in Your Industry?

Unfortunately, as Nokia and many other companies have learned, turning a blind eye as the industry environment begins to change can be a costly strategy. Managers need to recognize the different drivers and the types of strategic choices that are available to them. Depending on what you provide and your position in the new landscape, the opportunities and challenges will be different.

Beyond the development of novel end-user devices, infrastructures and services, convergence in the TIME industries has set in motion reorganization and realignment of business functions across the entire value chain. Whereas traditional “landline” carriers were once the only providers of telephony services, today you can purchase voice and data services from an array of IP-telephony providers. Convergence has put established products and services at risk, forcing old-line companies to search for new ways to survive.4

Convergence significantly affects the evolution of industry sectors and severely disrupts a company’s capabilities.5 Managers can observe the weak signals of convergence by analyzing patent data, scientific publications and classification schemes.6 For example, they can see how Standard Industrial Classification codes and patent filings overlap by monitoring scientific publications.7 However, it’s useful to have a framework for identifying strategic priorities and plotting operational responses. Based on a six-year study on convergence in the technology, information, media and entertainment sectors and its implications for the key industry participants, we have developed a framework that identifies four strategic pathways possible for companies facing industry convergence. (See “About the Research.”) We describe strategies companies have used and show how these strategies need to take into account the long-term implications of convergence in order to help companies sustain growth. We have also identified four important drivers of industry convergence: technological advancement, open architectures and standards, policy and regulatory reforms, and changes in customer expectations and preferences. (See “The Drivers of Convergence.”)

Four Strategic Pathways

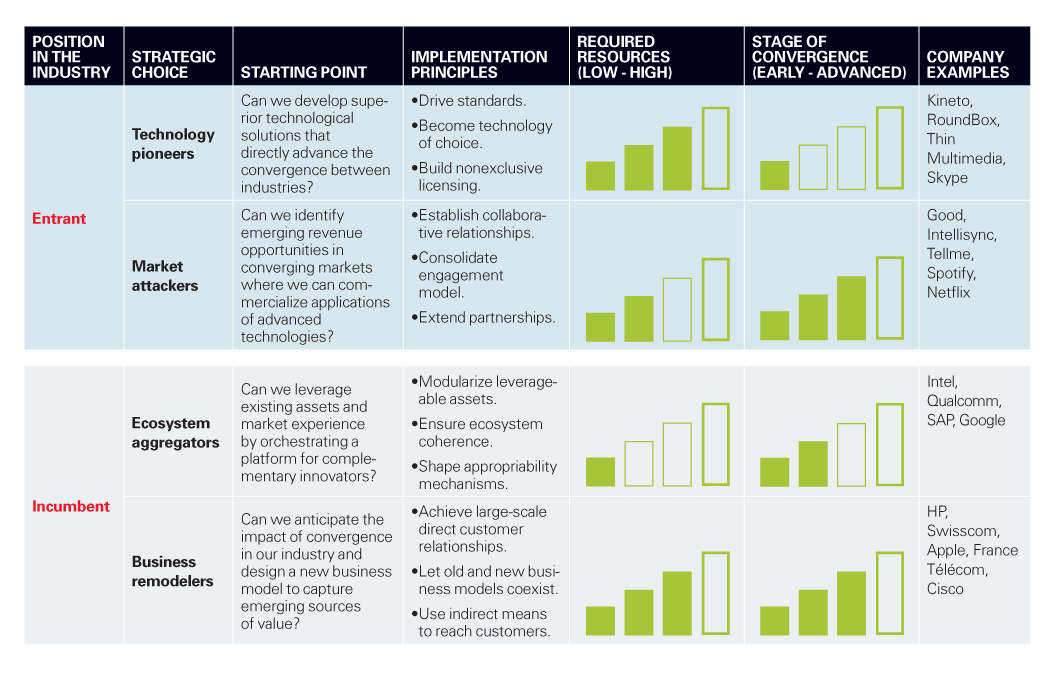

Companies have used four basic strategies to preserve and capture value during convergence: technology pioneer, market attacker, ecosystem aggregator and business remodeler. We will explore these pathways here. (See “Guiding Principles for Implementing Convergence Strategies.”)

The Technology Pioneer

Technology pioneers provide superior technological solutions that proactively contribute to the advancement of convergence between industries. They enter the market early and make strategic choices about the appropriate technological specialization as well as the control of intellectual property.

New ventures following this path recognize that they need to demonstrate the technological potential of their inventions and evaluate the conditions for early customer adoption. Consider video and data delivery provider Round Box, of Florham Park, New Jersey, which developed a novel way to stream video over mobile networks. The founders saw their venture as a “mobile broadcast convergence company,” with a technological solution for optimizing TV streaming to mobile phones. They already had a prototype. The challenges — and this is common among technology pioneers — were getting large carriers and network providers to embrace their technology and protecting their intellectual property. Successful technology pioneers we studied pursue these goals in several ways.

They drive standards. One way to advance your technology is to promote standardization activities within the industry. Kineto Wireless, a private company in Milpitas, California, for example, is a leading provider of IP-based over-the-top solutions to mobile companies. In advancing Unlicensed Mobile Access technology, which ensured standardized approaches for handsets and infrastructure equipment, Kineto Wireless established a market foothold for its own technology solutions.

A Changing Landscape in Mobile Handsets

They become the technology of choice. Technology pioneers need to become well recognized for their leadership, thus making it more difficult for downstream players to promote substitute products. Mountain View, California-based Thin Multimedia, which pioneered multimedia content delivery through new transmission technologies for wireless devices and TV sets, offers a good example. Although confident in the technological superiority of their offering, the founders worried that mobile handset vendors would enter this space and block other vendors’ entry. Technology pioneers are in a favorable position to work with a variety of equipment manufacturers and service providers simultaneously and can present themselves as independent.

They negotiate nonexclusive licenses. Technology pioneers avoid locking themselves into exclusive agreements. A more effective approach is to pursue multiple licensing agreements, as Kineto Wireless has done, thereby increasing the odds that their technology is adopted across the market. Although telecom operators have sought to acquire Kineto Wireless, the company has so far resisted. “It is always a balancing act,” notes one manager, “as all of your partners are also potential [mutual] competitors.”

Technology pioneers need to manage growth through internal development while at the same time driving product adoption and protecting their intellectual property. As one of the founders of Round Box noted, “We need to be smart about whom we work with and how we can leverage their connections, partners, expertise, without giving up our intellectual property.” He added, “We cannot get too close to anyone, but close enough to everyone. We need to keep neutrality, which gives us credibility.”

The Market Attacker

Market attackers try to exploit the commercial application of advanced technologies and tap into revenue opportunities generated by the fragmentation of well-established value chains.8 While different attackers vary in their technological expertise, they have similar marketing challenges. In particular, they must demonstrate the sustainability and profitability of their product offerings.

Most market attackers begin by identifying business opportunities with significant value. This often involves some sort of arbitraging between the parts of the market that have not converged yet and assembling pieces from previously distinct fields in new products or services. For example, in the late 1990s, Good Technology, a Sunnyvale, California-based software provider that focuses on multiplatform enterprise mobility, began offering solutions that allowed users to integrate their mobile email with their corporate email infrastructure before such capabilities were available on BlackBerries and iPhones. Similarly, Tellme Networks, of Mountain View, California, saw a market opportunity in linking existing telephone infrastructure to the increasingly robust variety of online content. Its idea was to allow customers to access information through a voice portal using voice commands.

Once opportunities have been selected, market attackers attempt to develop them quickly and nimbly. They collect early evidence on the market’s reactions and the way the offerings impact the established rules of the market. For example, Good Technology entered the market with a mobile messaging product that was designed to compete against the existing offerings of large, well-established telecom carriers. While many other companies had similar ideas for bridging corporate networks and mobile email, Good benefited by securing an early foothold.

A particularly effective strategy for market attackers is to team up with an incumbent and collaborate vertically in the value chain. We found that this often involves three steps.

They establish relationships. As an initial step, market attackers sound out potential partners, sometimes using intermediaries. This allows the attackers to iterate their value propositions and benefit from the market experience of their partners. As a member of Tellme’s management team recalled, the search process allowed them to “start looking into the other end of the telescope for what the compelling experiences are and what that would sound like for the enterprise; all of a sudden, it forced [us] to look differently at who we were selling to.” The analysis led Tellme to shift focus away from its initial consumer business and pursue corporate clients.

They consolidate the engagement model. The next step for market attackers is to consolidate their engagement model to advance the development of their offerings. Although they benefit from selling their applications in the short term, demonstrating the long-term value of what they can offer a partner is more important in many cases.9 Good Technology, for example, was able to attract the interest of several mobile network carriers based on the beta version of its email offering; based on what carriers saw, many decided to license Good’s products rather than develop competing services internally.10 Collaborations between market attackers and partner companies may expose asymmetries between the objectives and the expected time frames of the organizations. Some partners may be looking for a short-term solution, which may be inconsistent with the long-term growth targets of the product developers. Therefore, it’s important for all sides to think through the areas of overlap and potential differences in advance. Attackers will want to make sure that in the event of premature termination of the partnership, they are still able to make progress in developing their product.

They extend partnerships. In a third step, market attackers frequently explore ways of extending their partnerships. This involves drafting road maps for the partnership with different scenarios and outcomes and weighing different paths to enhance scale and reach. The outcomes can vary: Good set up an array of different partnerships with mobile carriers; others, including Tellme, were ultimately acquired.

Given that the window of opportunity is narrow, market attackers don’t have the luxury of taking a “wait-and-see” strategy. Instead, they need to act quickly to find ways to grow their businesses. Companies looking to defend themselves need to take this urgency into account when developing their own strategies. While attackers are better positioned to rapidly identify and capture new opportunities at the intersection of industry boundaries, the choice of appropriate timing for entering markets is critical for exploiting temporary advantage.11

The Ecosystem Aggregator

Ecosystem aggregators tend to be large companies that attempt to exploit the market opportunities resulting from a wave of emerging technologies. In contrast to young companies, they leverage their competences and market experience to establish an “innovation platform” aimed at complementary products and services. In doing so, they enhance the overall value of the core offerings, taking advantage of what are often called network effects.12

Network effects reinforce and extend the ecosystem aggregator’s proprietary advantages, such as its installed user base. SAP, the global provider of business application systems, offers a useful example. In 2003, SAP found itself at the crossroads between having a traditional, closed business application software model and the rise of social media. In response, it invited third-party developers and individual contributors to build on SAP’s products, which in turn enhanced the overall attractiveness of the core product.

Successful companies that follow this path can be thought of as platform leaders.13 They drive technological development in their ecosystem and derive advantages from their position within it, while at the same time establishing adequate economic incentives for ecosystem partners to invest in complementary innovations.14

Importantly, as ecosystem aggregators come to depend on the complementary products and services offered by partners, the ecosystem aggregators’ task is not just technical; it also involves ensuring that the business relationships are mutually beneficial. For example, Intel worked hard to capture the converging technologies underlying personal and mobile computing. It avoided imitating the technologies promoted by aggressive young competitors. Instead, Intel executives designed an integrated platform consisting of chips and software for the mobile industry, allowing others to create complementary products.

We found that ecosystem aggregators consistently utilize orchestration processes to coordinate, sustain and influence the activities of other ecosystem participants. These involve modularizing assets, ensuring coherence and shaping mechanisms.

They modularize assets. Ecosystem aggregators we studied modularized a set of assets that many players in the ecosystem could leverage. The purpose was to establish the core platform infrastructure where members could access and share tools, software and hardware components, and other assets, thereby reducing design and development redundancies. For example, Qualcomm, a semiconductor producer with a strong focus on wireless telecommunications products and services, established an application development platform that allows third parties to develop small programs, such as games, for phones built on Qualcomm hardware. Platform providers can decide which platform elements to keep closed and which ones are open for free usage. By providing a software development kit, Qualcomm could direct third-party developers and allocate tasks to a wider community of software developers.

They ensure ecosystem coherence. Aggregators can also ensure ecosystem coherence and alignment between innovation activities and the overall broader corporate strategy. They can accomplish this by determining access points to the platform and how partners share knowledge with other partners. In the developer forum, for example, the platform owner can moderate the discussion topics and specifications of interfaces.

They shape capture mechanisms. Finally, ecosystem aggregators design “capture mechanisms” that enable partners to secure value from their efforts. For example, ever since Intel initiated its “Intel Inside” campaign, other companies that wanted to build on Intel’s technology have been able to participate in co-branding and joint marketing. The value capture is not just monetary — it includes enhanced reputation.

Consistent with the pioneering work on platforms by scholar Michael Cusumano and colleagues,15 we found that a successful strategy for companies in converging environments is to learn to become innovation platform leaders. As Intel has shown, this involves engaging proactively in multiple activities within the ecosystems, including financing the codevelopment of new ventures and integrating them into the ecosystem.

The Business Remodeler

Companies with dominant positions in the market, a significant customer base, strong brand equity and established networks can become business remodelers. Such companies are well positioned to redefine the core business model and the related technological base.

Traditionally, dominant industry players created value through incremental innovations of their products and services. However, convergence can test the viability of core technologies and products, undermining the ability of such companies to perform. For example, between 2007 and 2010, formerly state-owned mobile telecom carriers in Europe saw average revenue per user decline by about 20%.16 As one manager of Swisscom, in Bern, Switzerland, observed, “It became clear that our core business is dying out — and much faster than we had believed.”

Convergence between information technologies and telecommunication has spawned new content services and applications — for example, voice-over-IP (VoIP) technology — that replicate services offered by traditional telecom carriers. As a result, Internet service providers have been able to challenge their market dominance.

Business remodelers need to develop an understanding of why value is shifting in their industry and identify the new sources of value. In the TIME industries, incumbents realized that convergence didn’t just mean that telephones, printers and music players were being replaced by more innovative devices. Convergence was also creating fundamentally new patterns for how people communicate, share information and access media content. Indeed, upon realizing that its pay-per-minute business model was being threatened by free VoIP service, Swisscom made a 180-degree strategy change and embraced VoIP. It invested heavily in wireless Internet technologies and became a leading provider of Wi-Fi hotspot infrastructure. In addition to allowing its customers to surf the Web, customers can use Wi-Fi to make free VoIP calls, enabling the company to increase customer loyalty and drive new traffic to its network.

Companies that successfully remodel their businesses pursue many of the same strategies in terms of their relationships with customers and their business models, including the following.

They build on customer relationships. Business remodelers typically begin by building direct relationships with their existing customer base. Swisscom, for example, was able to use its established position in the cellphone service business to test the viability of a new Wi-Fi hotspot service. Companies can also expand their customer base by creating new kinds of offerings. With the ever-increasing digitization of media and content, Hewlett-Packard faced important questions about the long-term future of its home printing business. HP assembled a team to scrutinize its business model. As one team member reflected, “Big companies have a problem, in that they force everything into their traditional metrics. The traditional metric for [us] was, how many pages are printed, how much ink is spent.” The analysis led to a new business: Rather than focusing on printers, HP’s new model centers on selling printed photos, which has been accelerated by the acquisition of Snapfish.

They let new business models coexist with old ones. Initially, at least, business remodelers are happy to let their new business models coexist with old models, with the understanding that if the new models are successful they will probably begin to dominate. That’s what happened when Apple launched its iTunes Music Store to support the iPod in 2003.17 iTunes turned out to be a huge success, and Apple gradually shifted many of its activities to the online store. Today Apple earns a significant share of its profits from sales of online music, movies, software and mobile apps.

They use indirect means to reach customers. Finally, business remodelers have opportunities to reach customers by circumventing traditional channels and using the back door instead. Specifically, they can use other industries as entry points, as Apple did with music content and mobile communications services and as HP has done with photo sharing. With industry convergence, customers may develop preferences for a particular company’s products and services, thereby enabling it to sell to new market segments with other existing technologies.

Making the Right Choices

Although successful new entrants and established companies respond differently in the face of industry convergence, the choices managers make are fortunately not etched in stone. They can be reversed. We found that smart companies have been able to adopt different strategies and pursue different paths depending on the circumstances. (See “Guiding Principles for Implementing Convergence Strategies.”)

Guiding Principles for Implementing Convergence Strategies

As the process of convergence advances and previously unrelated technologies and markets become interrelated, companies have the ability to change course. A technology pioneer might decide that it’s better to become a market attacker. Such a switch makes sense when the technological advantage has been exploited and the new challenge is shaping customer demands and preferences. Google, for example, has been on the forefront of search technologies to make information accessible in all formats and on all types of devices for many years. By doing so, it has blurred the boundaries between personal computers, mobile phones, collaborative tools and information retrieval. But Google has also attempted to use its position to shape markets, such as mobile phones.

As companies become older and larger, they need to rethink the assumptions underlying their strategic choices. Yahoo! provides an excellent example. Although it began as a technology pioneer offering innovative services such as Web-based email, value in the Internet has been shifting to other parts of the ecosystem, such as mobile applications. In response, Yahoo! is now becoming a business remodeler, offering new services, including Tumblr, the microblogging platform, which it acquired in June 2013.

Less mature, medium-sized companies face a wide range of strategic choices. To avoid being stuck in the middle, they need to scrutinize the benefits and risks of following any of the four strategies. At the same time, they must remain agile so they can move from one strategic path to another.

Of course, companies that pursue one strategic path have the opportunity to hedge their bets by partnering with another company pursuing a different strategy. For example, Kineto Wireless, which is a technology pioneer, has collaborated with several network carriers to promote combined fixed-line and mobile-line services. Among its partners is Swisscom, which is a business remodeler engaged in trying to bring new value to customers. Collaborations like these can generate value for both parties.

The process of convergence has greatly shaped the evolution of the telecommunications, information technology, media and entertainment industries, redefining the competitive landscape and presenting exceptional opportunities for strategic innovation and entrepreneurial market entry. No strategy is appropriate for every company. The right strategy will depend on a company’s financial and organizational resources, technological base and market knowledge. Whatever the circumstances, senior leaders need to understand the nature of the strategic challenges they face and the long-term implications of convergence.

Like surfing a big wave, riding the currents of technological change can be challenging. Leaders who don’t stay focused on the movement of the waves jeopardize the future of their company. A good surfer knows how important it is to identify and monitor emerging waves before they become big, and this analogy is telling.18 What starts small in a research laboratory can gather force in a short period of time and wash away an unprepared company. Technological waves are unpredictable and have the ability to change the market dynamic before you know it.

References (23)

1. F. Hacklin, “Management of Convergence in Innovation: Strategies and Capabilities for Value Creation Beyond Blurring Industry Boundaries” (Heidelberg, Germany: Physica/Springer, 2010); see also S. Brusoni, M.G. Jacobides and A. Prencipe, “Strategic Dynamics in Industry Architectures and the Challenges of Knowledge Integration,” European Management Review 6, no. 4 (winter 2009): 209-216; and I. Nonaka and G. von Krogh, “Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge Conversion: Controversy and Advancement in Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory,” Organization Science 20, no. 3 (May-June 2009): 635-652.

2. “TIME” abbreviation from European Parliament, “News Report: Jobs of the Future Require Multi-Skilling,” December 1, 1998, www.europarl.europa.eu; also see Arthur D. Little, “Web-Reloaded? Driving Convergence in the ‘Real World,’” December 2006, www.adlittle.com.

View Exhibit

View Exhibit View Exhibit

View Exhibit

View Exhibit

View Exhibit

Comment (1)

Praveen Kambhampati