How To Make Strategic Alliances Work

Topics

Strategic alliances — a fast and flexible way to access complementary resources and skills that reside in other companies — have become an important tool for achieving sustainable competitive advantage. Indeed, the past decade has witnessed an extraordinary increase in alliances.1 Currently, the top 500 global businesses have an average of 60 major strategic alliances each.

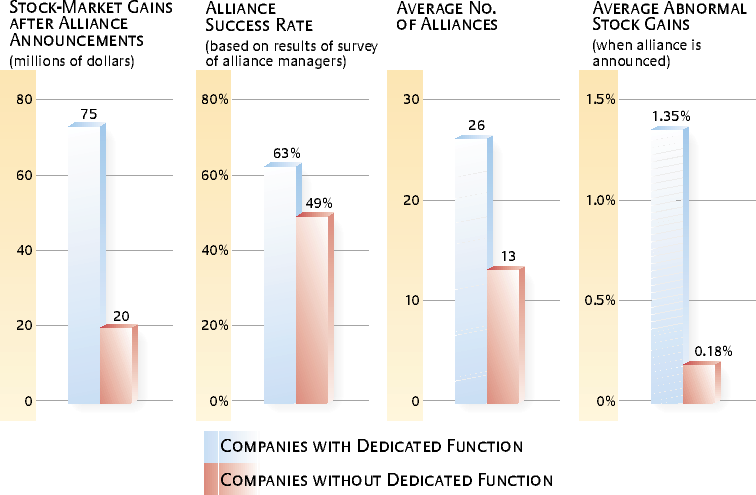

Yet alliances are fraught with risks, and almost half fail. Hence the ability to form and manage them more effectively than competitors can become an important source of competitive advantage. We conducted an in-depth study of 200 corporations and their 1,572 alliances. We found that a company’s stock price jumped roughly 1% with each announcement of a new alliance, which translated into an increase in market value of $54 million per alliance.2 And although all companies seemed to create some value through alliances, certain companies — for example, Hewlett-Packard, Oracle, Eli Lilly & Co. and Parke-Davis (a division of Pfizer Inc.) — showed themselves capable of systematically generating more alliance value than others. (See “A Dedicated Function Improves the Success of Strategic Alliances, 1993–1997.”)

How do they do it? By building a dedicated strategic-alliance function. The companies and others like them appoint a vice president or director of strategic alliances with his or her own staff and resources. The dedicated function coordinates all alliance-related activity within the organization and is charged with institutionalizing processes and systems to teach, share and leverage prior alliance-management experience and know-how throughout the company. And it is effective. Enterprises with a dedicated function achieved a 25% higher long-term success rate with their alliances than those without such a function —and generated almost four times the market wealth whenever they announced the formation of a new alliance. (See “Research Design and Methodology.”)

How a Dedicated Alliance Function Creates Value

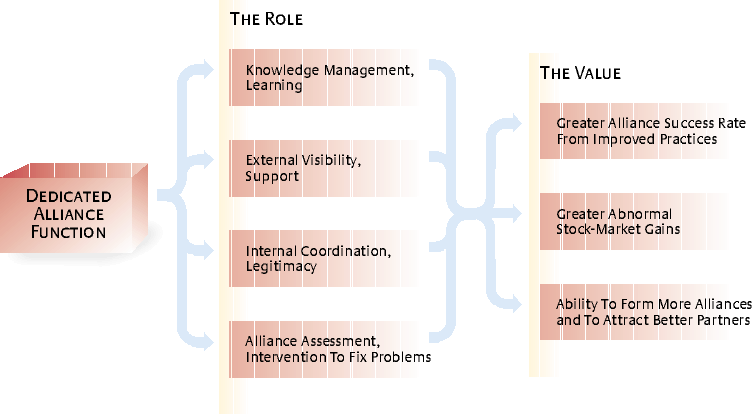

An effective dedicated strategic-alliance function performs four key roles: It improves knowledge-management efforts, increases external visibility, provides internal coordination, and eliminates both accountability problems and intervention problems. (See “The Role of the Alliance Function and How It Creates Value.”)

Improving Knowledge Management

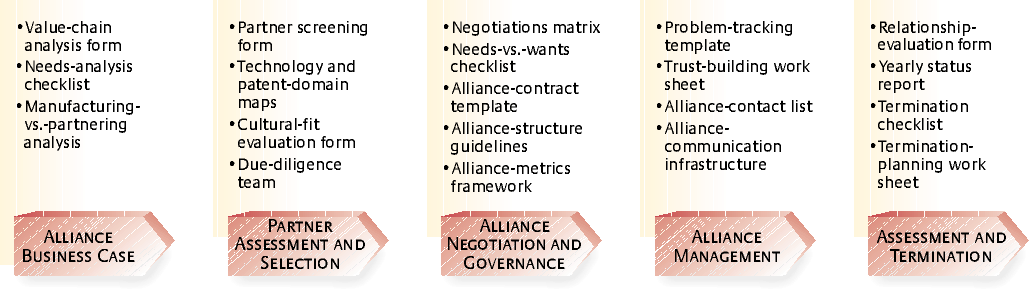

A dedicated function acts as a focal point for learning and for leveraging lessons and feedback from prior and ongoing alliances. It systematically establishes a series of routine processes to articulate, document, codify and share alliance know-how about the key phases of the alliance life cycle. There are five key phases, and companies that have been successful with alliances have tools and templates to manage each. (See “Tools To Use Across the Alliance Life Cycle.”)

Many companies with dedicated alliance functions have codified explicit alliance-management knowledge by creating guidelines and manuals to help them manage specific aspects of the alliance life cycle, such as partner selection and alliance negotiation and contracting. For example, Lotus Corp. created what it calls its “35 rules of thumb” to manage each phase of an alliance, from formation to termination. Hewlett-Packard developed 60 different tools and templates, included in a 300-page manual for guiding decision making in specific alliance situations. The manual included such tools as a template for making the business case for an alliance, a partner-evaluation form, a negotiations template outlining the roles and responsibilities of different departments, a list of ways to measure alliance performance and an alliance-termination checklist.

Other companies, too, have found that creating tools, templates and processes is valuable. For example, using the Spatial Paradigm for Information Retrieval and Exploration, or SPIRE, database (www.pnl.gov/infoviz/ spire/spire.html), Dow Chemical developed a process for identifying potential alliance partners. The company was able to create a topographical map pinpointing the overlap between its patent domains and the patent domains of possible alliance partners. With this tool, the company discovered the potential for an alliance with Lucent Technologies in the area of optical communications. The companies subsequently formed a broad-based alliance between three Dow businesses and three Lucent businesses that had complementary technologies.

After identifying potential partners, companies need to assess whether or not they will be able to work together effectively. Lilly developed a process of sending a due-diligence team to the potential alliance partner to evaluate the partner’s resources and capabilities and to assess its culture. The team looks at such things as the partner’s financial condition, information technology, research capabilities, and health and safety record. Of particular importance is the evaluation of the partner’s culture. In Lilly’s experience, culture clashes are one of the main reasons alliances fail. During the cultural assessment, the team examines the potential partner’s corporate values and expectations, organizational structure, reward systems and incentives, leadership styles, decision-making processes, patterns of human interaction, work practices, history of partnerships, and human-resources practices. Nelson M. Sims, Lilly’s executive director of alliance management, states that the evaluation is used both as a screening mechanism and as a tool to assist Lilly in organizing, staffing and governing the alliance.

Dedicated alliance functions also facilitate the sharing of tacit knowledge through training programs and internal networks of alliance managers. For example, HP developed a two-day course on alliance management that it offered three times a year. The company also provided short three-hour courses on alliance management and made its alliance materials available on the internal HP alliance Web site. HP also created opportunities for internal networking among managers through internal training programs, companywide alliance summits and “virtual meetings” with executives involved in managing alliances. And the company regularly sent its alliance managers to alliance-management programs at business schools to help its managers develop external networks of contacts.

Formal training programs are one route; informal programs are another. Many companies with alliance functions have created roundtables with opportunities for alliance managers to get together and informally share their alliance experience. To that end, Nortel initiated a three-day workshop and networking initiative for alliance managers. BellSouth and Motorola have conducted similar two-day workshops for people to meet and learn from one another.

Increasing External Visibility

A dedicated alliance function can play an important role in keeping the market apprised of both new alliances and successful events in ongoing alliances. Such external visibility can enhance the reputation of the company in the marketplace and support the perception that alliances are adding value. The creation of a dedicated alliance function sends a signal to the marketplace and to potential partners that the company is committed both to its alliances and to managing them effectively. And when a potential partner wants to contact a company about establishing an alliance, a dedicated function offers an easy, highly visible point of contact. In essence, it provides a place to screen potential partners and bring in the appropriate internal parties if a partnership looks attractive.

For instance, Oracle put the partnering process on the Web with Alliance Online (now Oracle Partners Program) and offered terms and conditions of different “tiers” of partnership (http://alliance.oracle.com/join/2join_pr2_1.htm). Potential partners could choose the level that fit them best. At the tier I level (mostly resellers, integrators and application developers), companies could sign up for a specific type of agreement online and not have to talk with someone in Oracle’s strategic-alliance function. Oracle also used its Web site to gather information on its partners’ products and services, thereby developing detailed partner profiles. Accessing those profiles, customers easily matched the products and services they desired with those provided by Oracle partners. The Web site allowed the company to enhance its external visibility, and it emerged as the primary means of recruiting and developing partnerships with more than 7,000 tier I partners. It also allowed Oracle’s strategic-alliance function to focus the majority of its human resources on its higher-profile, more strategically important partners.

Providing Internal Coordination

One reason that alliances fail is the inability of one partner or another to mobilize internal resources to support the initiative. Visionary alliance leaders may lack the organizational authority to access key resources necessary to ensure alliance success. An alliance executive at a company without such a function observed: “We have a difficult time supporting our alliance initiatives, because many times the various resources and skills needed to support a particular alliance are located in different functions around the company. Unless it is a very high-profile alliance, no one person has the power to make sure the company’s full resources are utilized to help the alliance succeed. You have to go begging to each unit and hope that they will support you. But that’s time-consuming, and we don’t always get the support we should.”

A dedicated alliance function helps solve that problem in two ways. First, it has the organizational legitimacy to reach across divisions and functions and request the resources necessary to support the company’s alliance initiatives. When particular functions are not responsive, it can quickly elevate the issue through the organization’s hierarchy and ask the appropriate executives to make a decision on whether a particular function or division should support an alliance initiative. Second, over time, individuals within the alliance function develop networks of contacts throughout the organization. They come to know where to find useful resources within the organization. Such networks also help develop trust between alliance managers and employees throughout the organization — and thereby lead to reciprocal exchanges.

A dedicated alliance function also can provide internal coordination for the organization’s strategic priorities. Some studies suggest that one of the main reasons alliances fail is that the partnership’s objectives no longer match one or both partners’ strategic priorities.3 As one alliance executive complained, “We will sometimes get far along in an alliance, only to find that another company initiative is in conflict with the alliance. For example, in one case, an internal group started to develop a similar technology that our partner already had developed. Should they have developed it? I don’t know. But we needed some process for communicating internally the strategic priorities of our alliances and how they fit with our overall strategy.”

Companies need to have a mechanism for communicating which alliance initiatives are most important to achieving the overall strategy — as well as which alliance partners are the most important. The alliance function ensures that such issues are constantly addressed in the company’s strategy-making sessions and then are communicated throughout the organization.

Facilitating Intervention and Accountability

A 1999 survey by Anderson Consulting (now Accenture) found that only 51% of companies that form alliances had any kind of formal metrics in place to assess alliance performance.4 Of those, only about 20% believed that the metrics they had in place were really the appropriate ones to use. In our research, we found that 76% of companies with a dedicated alliance function had implemented formal alliance metrics. In contrast, only 30% of the companies without a dedicated function had done so.

Many executives we interviewed indicated that an important benefit of creating an alliance function was that it compelled the company to develop alliance metrics and to evaluate the performance of its alliances systematically. Moreover, doing so compelled senior managers to intervene when an alliance was struggling. Lilly established a yearly “health check” process for each of its key alliances, using surveys of both Lilly employees and the partner’s alliance managers. After the survey, an alliance manager from the dedicated function could sit down with the leader of a particular alliance to discuss the results and offer recommendations. In some cases, Lilly’s dedicated strategic-alliance group found that it needed to replace the leader of a particular Lilly alliance.

When serious conflicts arise, the alliance function can help resolve them. One executive commented, “Sometimes an alliance has lived beyond its useful life. You need someone to step in and either pull the plug or push it in new directions.” Alliance failure is the culmination of a chain of events. Not surprisingly, signs of distress are often visible early on, and with monitoring, the alliance function can step in and intervene appropriately.

How To Organize an Effective Strategic-Alliance Function

One of the major challenges of creating an alliance function is knowing how to organize it. It is possible to organize the function around key partners, industries, business units, geographic areas or a combination of all four. How an alliance function is organized influences its strategy and effectiveness. For instance, if the alliance function is organized by business unit, then the function will reflect the idiosyncrasies of each business unit and the industry in which it operates. If the alliance function is organized geographically, then knowledge about partners and coordination mechanisms, for example, will be accumulated primarily with a geographic focus.

Identify Key Strategic Parameters and Organize Around Them

Organizing around key strategic parameters enhances the probability of alliance success. For example, a company with a large number of alliances and a few central players may identify partner-specific knowledge and partner-specific strategic priorities as critical. As a result, it may decide to organize the dedicated alliance function around central alliance partners.

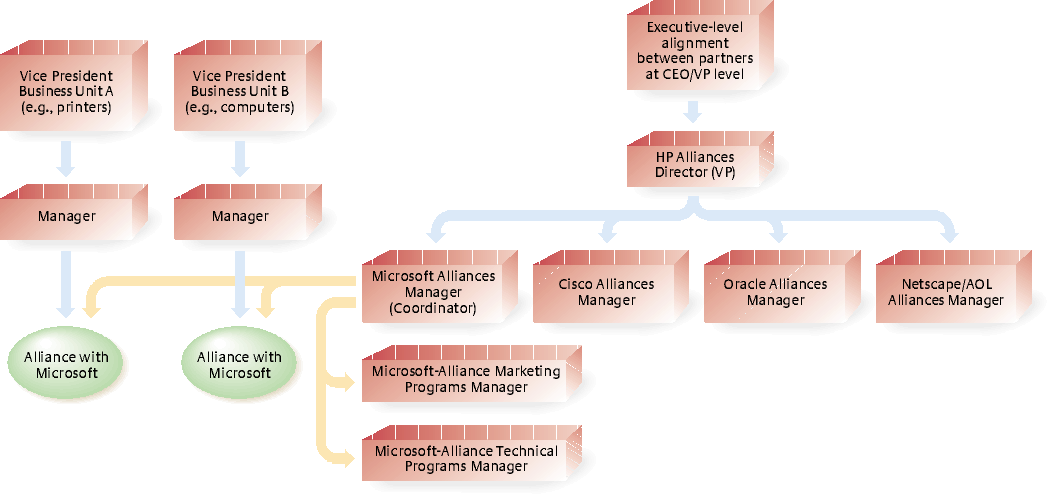

Hewlett-Packard is a good example of a company that created processes to share knowledge on how to work with a specific alliance partner. (See “Hewlett-Packard Alliance Structure for Key Alliance Partners.”) It identified a few key strategic partners with which it had numerous alliances, such as Microsoft, Cisco, Oracle and America Online and Netscape (now part of AOL Time Warner) among others. HP created a partner-level alliance-manager position to oversee all its alliances with each partner. The strategic-partner-level alliance managers had the responsibility of working with the managers and teams of the individual alliances to ensure that each of the partner’s alliances would be as successful as possible. Because HP had numerous marketing and technical alliances with partners such as Microsoft, it also assigned some marketing and technical program managers to the alliance function. The managers supported the individual alliance managers and teams on specific marketing and technical issues relevant to their respective alliances. Thus HP became good at sharing partner-specific experiences and developing partner-specific priorities.

Citicorp developed a different approach. Rather than organize around key partners, the company organized its alliance function around business units and geographic areas. In some divisions, the company also used an alliance board — similar to a board of directors — to oversee many alliances. The corporate alliance function was assigned a research-and-development and coordinating role for the alliance functions that resided in each division. For instance, the e-business-solutions division engaged in alliances that were typically different from those of the retail-banking division; therefore, the alliance function needed to create alliance-management knowledge relevant to that specific division. Furthermore, to respond to differences among geographic regions, each of Citicorp’s divisions created an alliance function within each region. For example, the e-business-solutions alliance group in Latin America would oversee all Citicorp’s Latin American alliances in the e-business sector. The e-business division’s Latin American alliance board would review potential Latin American alliances — and approve or reject them.

Organize To Facilitate the Exchange of Knowledge on Specific Topics

The strategic-alliance function should be organized to make it easy for individuals throughout the organization to locate codified or tacit knowledge on a particular issue, type of alliance or phase of the alliance life cycle. In other words, in addition to developing partner-specific, business-specific or geography-specific knowledge, companies should charge certain individuals with responsibility for developing topic-specific knowledge.

For example, when people within the organization want to know the best way to negotiate a strategic-alliance agreement, what contractual provisions and governance arrangements are most appropriate, which metrics should be used, or the most effective way to resolve disagreements with partners, they should be able to access that information easily through the strategic-alliance function. In most cases, someone within the alliance function acts as the internal expert and is assigned the responsibility of developing and acquiring knowledge on a particular element of the alliance life cycle. For some companies, it may be important to develop expertise on specific types of alliances — for example, those tied to research and development, marketing and cobranding, manufacturing, standard setting, consolidation joint ventures or new joint ventures. The issues involved in setting up such alliances can be very different. For example, whenever the success of an alliance depends on the exchange of knowledge — as is the case in R&D alliances —equity-sharing governance arrangements are preferable because they give both parties the incentives necessary for them to bring all relevant knowledge to the table. But when each party brings to the alliance an “easy to value” resource — as with most marketing and cobranding alliances — contractual governance arrangements tend to be more suitable.

Locate the Function at an Appropriate Level of the Organization

When done properly, dedicated alliance functions offer internal legitimacy to alliances, assist in setting strategic priorities and draw on resources across the company. That is why the function cannot be buried within a particular division or be relegated to low-level support within business development. It is critical that the director or vice president of the strategic-alliance function report to the COO or president of the company. Because alliances play an increasingly important role in overall corporate strategy, the person in charge of alliances should participate in the strategy-making processes at the highest level of the company. Moreover, if the alliance function’s director reports to the company president or COO, the function will have the visibility and reach to cut across boundaries and draw on the company’s resources in support of its alliance initiatives.

A Critical Competence

Companies with a dedicated alliance function have been more successful than their counterparts at finding ways to solve problems regarding knowledge management, external visibility, internal coordination, and accountability — the underpinnings of an alliance-management capability.

But although a dedicated alliance function can create value, success does not come without challenges. First, setting up such a function requires a serious investment of the company’s resources and its people’s time. Businesses must be large enough or enter into enough alliances to cover that investment. Second, deciding where to locate the function in the organization — and how to get line managers to appreciate the role of such a function and recognize its value — can be difficult. Finally, establishing codified and consistent procedures may mean inappropriately emphasizing process over speed in decision making.

Such challenges exist. But the company that surmounts them and builds a successful dedicated strategic alliance function will reap substantial rewards. Companies with a well-developed alliance function generate greater stock-market wealth through their alliances and better long-term strategic-alliance success rates. Over time, investment in an alliance-management capability enhances the reputation of a company as a preferred partner. Hence an alliance-management capability can be thought of as a competence in itself, one that can reap rich rewards for the organization that knows its worth.

References

1. B. Anand and T. Khanna, “Do Companies Learn To Create Value?” Strategic Management Journal 21 (March 2000): 295–316.

2. P. Kale, J. Dyer and H. Singh, “Alliance Capability, Stock Market Response and Long-Term Alliance Success,” Academy of Management Proceedings (August 2000).

3. J. Bleeke and D. Ernst, “Collaborating To Compete” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993); and “The Way To Win in Cross-Border Alliances,” The Alliance Analyst, March 15, 1998, 1–4.

4.“Dispelling the Myths of Alliances,” Outlook (1999): 28.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

A helpful resource is John Harbison and Peter Pekar’s “Smart Alliances: A Practical Guide to Repeatable Success,” published in 2000. For a more scholarly development of ideas in the article, we recommend: Y. Doz and G. Hamel’s 1998 book from Harvard Business School Press, “The Alliance Advantage: The Art of Creating Value Through Partnering”; J. Dyer and H. Singh’s 1998 “The Relational View” in Academy of Management Review; R. Gulati’s “Alliances and Networks,” which appeared in Strategic Management Journal in 1998; “Building Alliance Capability: A Knowledge-Based Approach” from the 1999 Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings and “Alliance Capability, Stock Market Response and Long-Term Alliance Success” from the 2000 Academy of Management Proceedings, both by P. Kale and H. Singh. Also of interest are J. Koh and N. Venkatraman’s “Joint Venture Formations and Stock Market Reactions,” which appeared in 1991 in Academy of Management Journal; M. Lyles’ “Learning Among Joint-Venture Sophisticated Companies” in a 1998 Management International Review special issue, and Bernard Simonin’s 1997 article, “The Importance of Collaborative Know-How” in Academy of Management Journal.