Should Top Management Relocate Across National Borders?

In today’s increasingly international world, it’s not uncommon for multinational companies to move some element of their headquarters to another country. Here’s how to evaluate the strategic costs and benefits of such decisions.

Topics

A desire to be close to its major global customers led Halliburton Co., an international oil services group, to relocate the company’s CEO from its headquarters in Houston, Texas, to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

International relocations of entire corporate headquarters are a rare phenomenon. But the relocation of elements of headquarters — such as the offices of top management team members, core functions like finance, R&D or shared services — is happening more and more, triggered by the increasing internationalization of markets and industries. At present, international relocations of corporate headquarters elements can most clearly be observed — as a kind of early warning — in highly internationalized, small, open economies, such as Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands, that traditionally host a relatively high number of multinationals’ corporate headquarters. However, multinationals currently hosted in larger countries are also affected by increasing levels of internationalization.

The international oil services group Halliburton Co. offers an example. In 2007, the globalization of Halliburton’s markets and industry led Halliburton to shift its business focus from the United States to the Middle East. The desire to be close to its major global customers — national oil companies in the Eastern Hemisphere — and the oil industry’s center of gravity (the Eastern Hemisphere accounts for three-quarters of proven fossil fuel reserves) drove the decision to relocate Halliburton’s CEO from headquarters in Houston to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. Other elements of the headquarters remained in Houston.

We researched corporate headquarters decisions of the 100 largest multinational corporations headquartered in the Netherlands, which has one of the world’s most internationalized economies, making it an excellent country in which to investigate this trend. Fifty-eight Dutch multinationals participated in our survey, including Fortune Global 500 corporations such as Royal Dutch Shell, ING Group, Royal Philips Electronics, Unilever and Heineken. Our survey results indicate that 57% of the participating multinationals have already internationally relocated elements of their headquarters. Furthermore, 67% intend to start or to continue relocating within the next five years.

The research on which this article is based was both qualitative and quantitative. First, we interviewed top management team members from 10 of the 100 largest Dutch multinational corporations; the interviews helped us to create an in-depth and fine-grained understanding of top management team members’ office relocations, particularly in terms of the various drivers and barriers and the related decision processes and relocation options. We then gathered and analyzed quantitative data by means of a questionnaire and fact sheets. We invited the CEO and other top management team members of the 100 largest multinational corporations headquartered in the Netherlands to participate in the quantitative research, and we received complete data for 58 companies. To test for nonresponse bias we examined differences between respondent companies and nonrespondent companies in terms of sales volume, industry and level of internationalization; no significant differences appeared, indicating that nonresponse bias may not be a problem. To avoid issues of single informant data, the questionnaire was filled out not only by the CEO of each of the companies but also by the top management team members of four functional areas.

Assessing the Strategic Benefits and Costs of Relocation

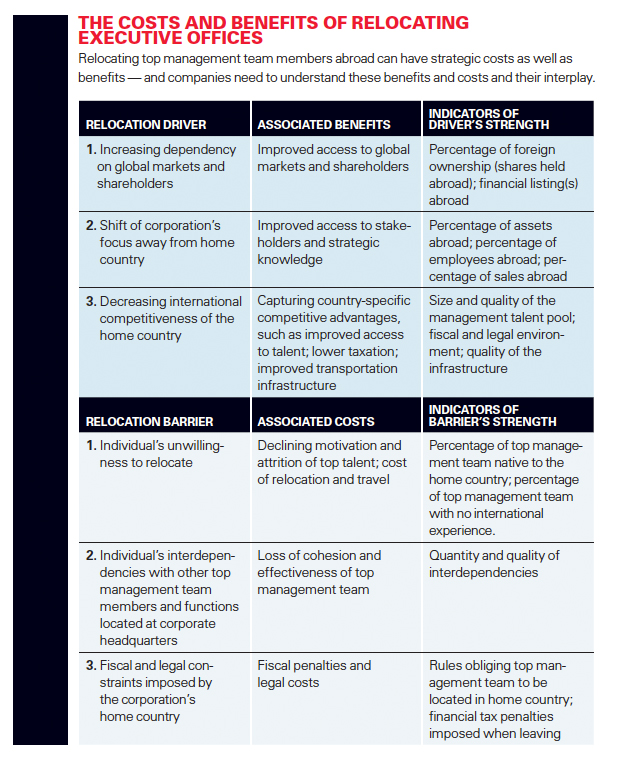

Despite the growing practice of internationally relocating top executives, our research shows that relocating top management team members abroad resulted in higher performance for only about half of the corporations responding to our survey. The reason is that such relocations — despite their strategic benefits — also entail strategic costs. (See “The Costs and Benefits of Relocating Executive Offices.”) To make well-informed decisions, executives need to understand these benefits and costs and their interplay.

The benefits of international relocation of top management team members’ offices are strategic: better access to knowledge and improved relationships with stakeholders abroad, resulting in more effective decision making. The barriers against international relocation of such offices include personal ties, functional interdependencies and fiscal and legal constraints at the individual, organizational and country level. These barriers imply that physical relocation of top management team members to a new host country is not always the best option for the corporation. Fortunately for large corporations, relocating an entire office is just one of three possible options: 1) physical relocation of a top management team member’s office; 2) no office relocation but usage of international communications technology and international travel; or 3) dual offices. The decision on which of these three options is best depends on the strength and interplay of the relocation drivers and barriers. Below is our explanation of all three options, followed by our conclusions about the drivers and barriers.

Option 1: Relocation of a Top Management Team Member’s Office The large Dutch information services group VNU (acquired in 2007 by a private equity consortium and renamed The Nielsen Co., now Nielsen Holdings) provides an illustration of the relocation of an executive’s office. VNU expanded into the United States in the 1990s and early 2000s by taking over a number of U.S. companies, including ACNielsen. In 2004, as a direct byproduct of these acquisitions, the company’s center of gravity had shifted from Europe to the United States. To get closer to the business, VNU’s Dutch CEO decided to relocate his office from the Netherlands to the New York headquarters of one of the acquired companies. Primarily for tax reasons, VNU’s corporate headquarters and most of the staff remained at the fiscal seat in the home country. Because of functional interdependencies, the CEO wanted the CFO, also a Dutch national, to relocate to New York too. However, for personal reasons the CFO was unwilling to expatriate. Although the CEO and the CFO held long and frequent conference calls to manage functional interdependencies, often many times a day, it did not prove to be sufficient or effective. Eventually, in 2005 the CFO retired and his successor relocated his office to New York.

Option 2: No Office Relocation but Extensive Usage of International Communications Technology and Travel Of all the management levels, top management team members rely most on soft and tacit information. Even the most advanced communication tools cannot match the richness of face-to-face interaction. Therefore, top executives also need to engage in international travel to visit stakeholders and have face-to-face meetings. Our respondents report high amounts of time spent on international travel. “I spend up to half of my time outside the home country” was a common refrain.

Option 3: Dual Offices This option means that the top management team member maintains an office in the corporation’s home country, and has a second office in a host country. The Fortune Global 500 corporation Royal Philips Electronics provides an example. The path to dual offices began in 2001, when Royal Philips Electronics expanded through a series of international acquisitions. At the time, the executive vice president of the health-care division was located in Best, in the Netherlands. But after the acquisition, the division’s geographic business focus shifted to the United States. To manage the trade-off between the strategic benefits of the geographic shift and the costs — for example, losing executive team cohesion and effectiveness because of the interdependencies between the health-care division executive vice president and the corporate headquarters — in 2006, Philips decided to establish a second office for the executive vice president in Andover, Massachusetts, the hub of the division’s overseas activities. But he still kept his office, with a small part of the staff, at the corporate headquarters in Amsterdam.

In general, physical relocation of top management team members to a new host country is not an “all or nothing” issue. In fact, in a high percentage of cases, full-fledged office relocation is not the best option for the corporation. Fortunately, other options are available, including the increased usage of communications technology and international travel, as well as the operation of dual offices. Only by assessing the drivers of top management team relocation, and weighing them against the barriers, can a corporation make the best decision.

Comment (1)

michaelqazqaz