The Gap Between the Vision for Marketing and Reality

The ideal role of marketing was articulated 60 years ago. How close to the ideal have we come by now?

Topics

The growing number of chief marketing executives reflects the increasing importance companies attach to marketing. Yet the average tenure of a chief marketing officer (CMO) is three and a half years, well below that of the typical CEO. Both the prevalence of the CMO position and its precariousness give rise to the question: Has marketing realized the vision to which its adherents have long aspired? A recent global survey of CMOs reveals both how far marketing has come and where there is room to grow.

The Vision for Marketing

For more than 60 years, marketers have had a clear vision of the ideal role of marketing, which consists of two core ideas. One is the concept of the “marketing mix,” which dates to the late 1940s. Harvard’s Neil Borden, while president of the American Marketing Association, realized there was no set formula for successful marketing. Instead, the marketer must choose the best mix from the set of all possible mixes. Jerome McCarthy later codified the mix in the classic 4Ps of marketing — product, price, place and promotion. The task of the marketing executive is to have control of, or at least influence on, all of the 4Ps and blend them to produce the best value.

The second fundamental idea is that marketing decisions should be based on a solid understanding, supported by hard data, of target customers and other stakeholders. Anchoring decisions in data has become part of the bedrock vision of marketing. These two core components — control of the marketing mix and customer-oriented, data-based decision making — are fundamental to the field’s shared vision of marketing. It has been over a half century since that vision, now clearly spelled out in marketing textbooks, took shape. So what is the status of the field relative to the vision?

How Chief Marketing Officers Rate Their Influence

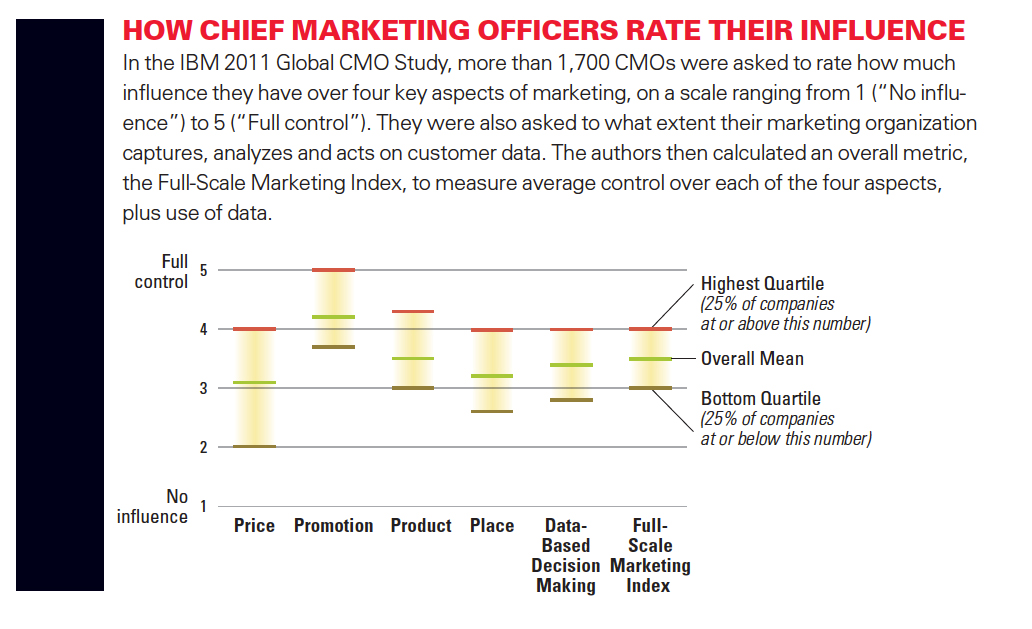

To answer this question, we turned to the IBM 2011 Global CMO Study, consisting of face-to-face, hour-long interviews with more than 1,700 CMOs from 64 countries and 19 industries. CMOs were asked to rate how much influence they have over each of the 4Ps. They rated their influence on a scale ranging from 1, “No influence,” to 5, “Full control.” CMOs were also asked to what extent their marketing organization captures, analyzes and acts on customer data. We calculated an overall metric, which we call the Full-Scale Marketing Index, to measure both average control over each of the 4Ps and use of data. (See “How Chief Marketing Officers Rate Their Influence.”) The results reveal that on average CMOs rate themselves and their companies at the 3.5 level on the Full-Scale Marketing Index — distinctly below the top mark. The CMO survey provides insights into the reasons for this gap.

Where the Marketing Ideal Is Further Away

CMOs rate themselves and their companies most highly on the promotion part of the marketing mix. On average they give themselves a 4.2, and at least 25% of companies indicate they have “full control” over promotion. That assessment is not surprising. Promotion has a natural link to marketing as an organizational function.

Control of the product element of the mix is rated next most highly at 3.5, followed by use of data at 3.4. Control over place gets a 3.2, and control over price a 3.1. At least 25% of companies score 2 or lower when it comes to controlling price, and the bottom quartile for place is 2.6 or lower. Clearly, the vision that marketers control aspects of decision-making beyond promotion has not been fully realized. Nor has the use of data and analysis approached the primacy of promotion. One could argue that 3.5, while short of the ideal vision of full-scale marketing and skewed toward promotion, is not so bad. The fact is, however, that some companies are much further away from the vision than others.

One explanation is that some companies may be in industries that are less suited to marketing. Industrial product companies, for example, are often thought of as not needing to be as marketing-oriented as other companies. When we looked at how companies’ ratings differed by industry, we found that each industry had at least one company with high control over every part of the marketing mix, as well as companies with low control. Among industrial products companies, 17 of 116, or 15 percent, were in the high-control category. While there is some truth to the idea that some industries do not favor marketing, there are also plenty of exceptions. A company’s industry does not lead it to a lower level of marketing. Nor was location an explanation. The study shows that there are substantial numbers of organizations in all regions at all levels of control.

Do some companies not adhere to the marketing vision because they have embraced new technologies such as online marketing and social media? We checked whether there were differences of this kind in the companies surveyed. It turns out that organizations with high control over the 4Ps and data use are also the most forward-looking — with greater intentions to increase use of newer tactics such as tablet and mobile applications, social media, e-mail marketing and predictive analytics. Companies that have mastered traditional marketing tend to be the ones embracing the new forms.

Does How Close You Are to the Vision Matter?

Given that only a minority of companies come close to the full-scale marketing vision, how concerned should companies be? The CMO study provides some intriguing clues.

When asked how well they are dealing with change and complexity, CMOs tended to rate their success as only moderate, and differences among companies were small. This said, companies with high control over the marketing mix and data use did rate their success higher than the others, while low-control companies ranked themselves lower in success. And on the whole, high-control companies felt more prepared for future threats and increasing complexity in the marketplace, while low-control companies felt less prepared.

One would ideally like to relate the Full-Scale Marketing Index to actual economic performance, but many other variables would have to enter such an analysis. The survey does, however, offer one tantalizing clue. CMOs indicated the position of their company within their industry on a scale from 1, “Significantly underperform the industry,” to 5, “Significantly outperform the industry.” (For companies for which data is available, these ratings actually do correlate with financial performance.) Again, differences were limited, but companies with high control over the marketing mix and data use stood out as being in better shape.

The CMO survey also suggests a crucial obstacle to achieving the vision of marketing: the role of the CMO vis-à-vis the CEO and other C-suite members. When CMOs were asked to rate how their entire senior management team would score marketing’s contribution to the business, CMOs at companies with high control over the marketing mix and data use anticipated higher marks than the others.

It is difficult to disentangle cause and effect here. Is high regard by senior management, at least as reported by the CMO, a reflection or a cause of effective marketing? Is a lack of regard by other C-suite executives an obstacle to realizing the marketing vision? A statistical analysis of the correlation between the Full-Scale Marketing Index and top management’s view of marketing holds up even when we control for how effective marketing has been and is expected to be. This suggests that top management’s evaluation of marketing is indeed a cause of marketing success and not a consequence.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Thirty-three years ago, one of this article’s authors, Philip Kotler, called for marketers to be more effective at “systems management,” striking a balance between the needs of the marketing mix and those of other business functions, and even of external entities such as distributors and suppliers. As organizations and markets have become more complex, the need for a less compartmentalized view of marketing is even more apparent today. To the extent that the traditional vision of marketing distracts companies from integration, it may cause marketing to undermine itself, leading as much to the failure of the vision as to its success. Going forward we should ask: What can CMOs do to become as indispensable as they should be? Should they play a larger role than simply trying to increase the influence of traditional marketing? Perhaps progress lies in integrating the goals of marketing into a larger, more encompassing vision of markets and consumers.