Cracking the Code of Mass Customization

Most companies can benefit from mass customization, yet few do. The key is to think of it as a process for aligning a business with its customers’ needs.

Topics

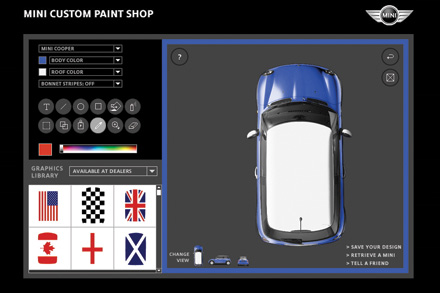

Mini Cooper customers can design the roofs of their vehicles by using an online tool kit. That software has enabled BMW to tap into the custom after-sales market.

Courtesy of Mini Cooper.

The concept of mass customization makes sense. Why wouldn’t people want to be treated as individual customers, with products tailored to their specific needs? But mass customization has been trickier to implement than first anticipated, and many companies soured on the approach after a number of high-profile flops, including Levi Strauss & Co.’s failed attempt at manufacturing custom jeans. Now, executives tend to think of mass customization as a fascinating but impractical idea, the preserve of a small number of extreme cases, such as Dell Inc. in the PC market.

Our research suggests otherwise. Over the past decade, we have studied mass customization at a number of different organizations, including a survey of more than 200 manufacturing plants in eight countries. (See “About the Research.”) From that investigation, we found that mass customization is not some exotic approach with limited application. Instead, it is a strategic mechanism that is applicable to most businesses, provided that it is appropriately understood and deployed. The key is to view it basically as a process for aligning an organization with its customers’ needs. That is, mass customization is not about achieving some idealized state in which a company knows exactly what each customer wants and can manufacture specific, individualized goods to satisfy those demands—all at mass-production costs. Rather, it is about moving toward these goals by developing a set of organizational capabilities1 that will, over time, supplement and enrich an existing business.

That set of fundamental capabilities is threefold: (1) the ability to identify the product attributes along which customer needs diverge, (2) the ability to reuse or recombine existing organizational and value-chain resources and (3) the ability to help customers identify or build solutions to their own needs. Admittedly, the development of these capabilities requires changes that are often difficult because of powerful inertial forces in an organization, but that makes the argument more compelling: Those companies that are able to develop the capabilities will be able to enjoy long-lasting competitive advantages. In addition, we believe that many obstacles can be overcome by using a variety of approaches, and that even small improvements can reap substantial benefits.

References (19)

1. For a definition of the concept of strategic capabilities, see K.M. Eisenhardt and J.A. Martin, “Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They?” Strategic Management Journal 12, no. 10 (2000): 1105-1121.

2. J.B. Pine II, “Mass Customization—The New Frontier in Business Competition” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 1993).

Comments (2)

Ajit Kini

bruces