The New E-Commerce Intermediaries

Topics

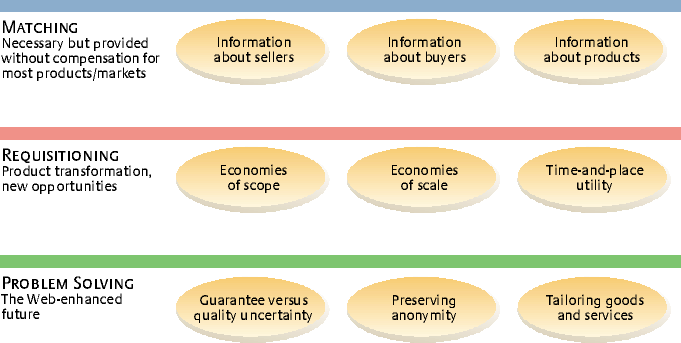

Not long ago companies embracing the Internet thought e-commerce meant cutting out intermediaries. Businesses would go directly to customers and save money. Times change and perceptions crumble. Companies discovered it isn’t so easy to do everything alone. Middlemen are still needed. However, their role is changing. Only those middlemen and producers who understand just exactly how the intermediary role is changing can make good on the promise of e-commerce. Intermediaries add value. Three of the nine ways they currently add value (providing information about buyers, sellers, and goods or services) probably will change; middlemen will have to provide all that gratis. Another set of functions (economies of scale, economies of scope, arranging convenient times and places) will survive in a new form. The final three activities (reducing uncertainty about quality, preserving anonymity and tailoring offerings) represent growth opportunities for specialist companies and supplier partners.

Consider the upstream company, the one that expected to use the Web to cut out middlemen. How does it succeed today? It weaves a distribution partnership and finds new ways of compensating members. It moves away from selling wholesale and leaving the channel partner to fight for a markup. The proper response to the Web for suppliers is to embrace channel partners, not replace them; the proper response for channel intermediaries is to leverage, rather than dread, Web-enabled commerce. Providers will get closer to their customers, all right, but not by a direct path.

The Travels of a Light Bulb

Research in the 1950s established that even General Electric didn’t know how a light bulb got from factory to kitchen fixture. The product took a complex route through multiple downstream organizations.1

Today many producers regard the opaqueness of distribution channels as covering inefficiency. Their own output they deem desirable and certain to find its market. Downstream channel members don’t add value; they add costs, snatch margin and muffle the voice of the customer. The shorter, simpler and more linear the distribution chain, the better, producers say.

The Internet was supposed to enable simplicity. Business gurus predicted it would bring manufacturers in direct contact with end customers. Channel partners looked upstream fearfully, less worried about competition from new, Internet-only channels than the prospect of competing with suppliers. Mistrust flourished.

The idea was that the Internet would help both consumers and industrial buyers make purchases like the rational (RAT) economic actors who populate economics textbooks. RATs are bargain hunters. They inform themselves about all possible choices, performing mental calculus to convert disparate options into the number of units of utility, or satisfaction, that each choice provides, price aside. Oh, the cold-eyed, practical RAT, factoring in only documented, substantial differences! Having rendered everything comparable, RATs then decide how much utility is needed. Unencumbered by perceptions, mistakes, bias, intuitive preference or romance, these theoretical marvels line up equal-utility choices and pick the least expensive one.

At first, observers thought the Internet would turn that abstraction into reality. Web sites would help RATs compare possibilities and purchase the cheapest option with one click. In that ruthlessly efficient world, there would be no room for middlemen. Distributors, merchants, brokers and agents, who used to get credit for sales, would no longer be paid. Channels would be straightforward, the producer mastering the details of every transaction, the identity of every customer.

However, the opposite is occurring. The downstream part of the supply chain is becoming less straightforward, more fragmented and often longer. Why?

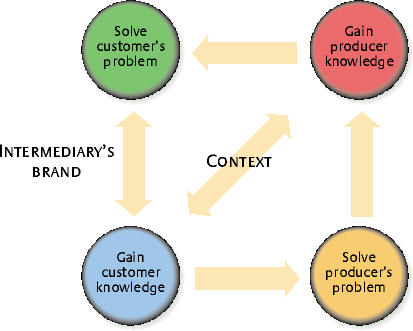

The conventional view of intermediaries overlooks why they exist; they solve customers’ problems and, thereby, producers’ problems. Their position on the high ground between both groups enables them to create value and charge for it. Although the Internet alters what the intermediary can do from the lookout post, it doesn’t obliterate the inherent advantage of the position.

In shifting power to buyers, the Internet actually boosts intermediation. That’s because the Web, while empowering buyers, also presents new problems. Customers are starting to designate channel members to solve specific challenges, spurring changes in how intermediaries add value and get compensated. Some advantages of the central position are becoming necessary costs of doing business and aren’t generating a return. Nevertheless, downstream channel members who understand the true potential of the Web are inaugurating a golden age of distribution.

New intermediaries are emerging that don’t fit traditional categories. Metaphors are changing. For example, “channel of distribution,” from the French “canal,” suggests a loaded barge floating straight from point of origin to point of last purchase. It supports the producer’s notion that little useful happens after a product leaves the factory. A new vocabulary is needed to capture a more complex and fragmented mesh of Internet problem solvers.

Although to customers a simple, linear channel will still seem to flow from suppliers, the reality will be complex. The best metaphor is a service hub. A hub has a center, and at the center is the organization with which the customer places the order, which assembles the rest of the offer, calling on other hub members. E-commerce hubs will be assembled quickly, like interlocking puzzle pieces. Customers will collaborate with suppliers to create service hubs that materialize in real time.

For example, a corporate customer may contact the Web site of MadeToOrder.com with a vague idea of creating logo merchandise. The customer thinks this is the channel of distribution, but in reality it is the center of a hub. The hub site guides the customer through the process of generating ideas (mugs? stopwatches? clothing?) and points out issues to be resolved (cobranding the merchandise, adapting the logo to the item). A human account team stands ready to intervene at the customer’s request. The hub manages a complex custom-production process that involves multiple suppliers and meshes with the customer’s own logo-approval process, cutting time by two-thirds.

What other services does the hub provide? Customers need security for their stored logos and access only by designated personnel (such as brand managers or authorized buyers). Then there are such ancillary services as credit, speciality packaging and special handling. Meanwhile, as the hub center assembles providers, each provider is activating its own providers. (A shirt maker, for example, may be ordering a particular shade of dye to match the logo.) And the lookout is spotting related customer needs to address — an employee store, a trade-show booth or advertising services. All the while, customers think they’re dealing with one entity, the Web site.

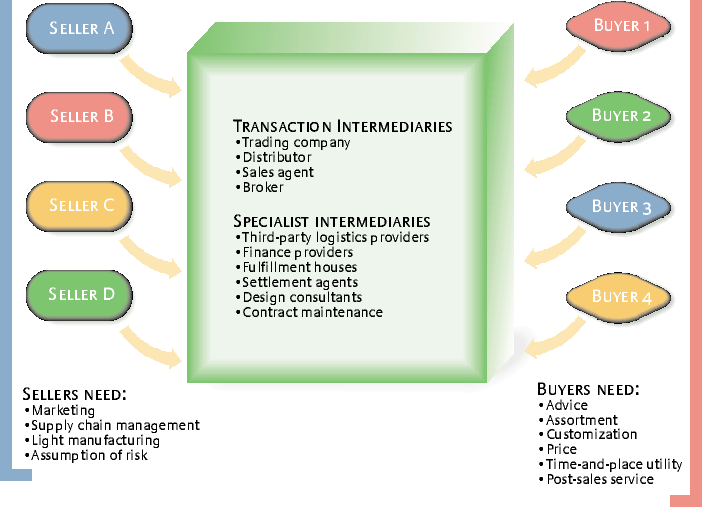

How Do Intermediaries Create Value?

Being in between is precisely why intermediaries are valuable. Customers make purchases to meet needs, and those needs come in groups that intermediaries are best situated to serve. Engineers making a complex product have a group of needs, including logistics, pre-sales assistance, configuration, testing, advertising, financing, sale negotiation and help settling the transaction. They also need post-sale service, such as customization, troubleshooting, warranties and maintenance. By bundling such services, intermediaries craft an augmented product for buyers.

In theory, the supplier could break those services into component pieces and contract out for each piece. In practice, that hasn’t worked, because suppliers must coordinate multiple providers, many of which would be too small to function alone as micro specialists without charging a lot.2 With the Internet, specialists can extend their reach and charge less, making it easier for suppliers to work with them.

But that economic shift doesn’t necessarily undermine generalist go-betweens and their lookout position. While the generalist intermediaries serve the interrelated needs of each customer and the family of needs of the customer base, they gather knowledge: which customer units make decisions, how they function, what they perceive about each brand and its competition, and how they use what they buy. No producer makes brands that fit all the needs of every customer in a product category. But intermediaries sell adjacent and complementary products, and thus, unlike producers, they get to see how the customer uses the items. Intermediaries are the best-informed players.

Manufacturers sometimes create their own distribution arms, hoping to capture the lookout position. But because they don’t make desirable products in every category, they don’t get the full view. They could try carrying competitors’ products, but that is not a solution, given that competing and complementary manufacturers fear not being represented fairly.

True intermediaries are neutral about suppliers. They represent the buyer. Consider Web-based myCFO, which offers independent financial advice to wealthy individuals. Netscape founder Jim Clark set it up out of frustration with vertically integrated banks. Says Clark, “Morgan Stanley would offer advice, but it would include mostly Morgan Stanley products. The same goes for the other banks. I wanted unbiased advice.”3

Merck’s unsuccessful stab at drug distribution through Medco demonstrates how manufacturers have misunderstood distributors’ economic role. The goal is not to move producers’ goods and services downstream but to solve problems for buyers — and consequently to solve problems for sellers. (See “How Intermediaries Traditionally Aggregate Needs of Buyers and Sellers.”) In fact, intermediaries who can’t solve buyers’ problems have nothing to offer a seller. Paradoxically, to generate value for producers, go-betweens must be customer-oriented, not producer-oriented. They must solve the difficulties facing the buyer and holding up the sale. They don’t take orders; they create orders.

Co-Opting the Web

In the first Internet wave, everyone wanted to be an Internet intermediary. With no real estate and no inventory, intermediaries would coin money, generate unparalleled customer knowledge and dictate terms upstream. When new middlemen failed to displace old ones, a second wave broke. Now the goal was to unload go-betweens entirely. That wave ebbed with the collapse of business-to-business e-marketplaces and the reluctance of producers to threaten long-standing distribution relationships.

What’s next? Intermediaries who solve customer problems —and producers who iron out problems with middlemen partners — will thrive, but it won’t be business as usual. The networked global economy will transform how intermediaries create value and realize revenue from their lookout position. (See “How Intermediaries Will Create Value on the Web.”) First, profits based on matching customer to supplier through superior data will decline in most cases. Second, profits based on calling up what customers want at a particular time and place will shift because the nature of such requisitioning will shift. Finally, profits based on guaranteeing quality and on tailoring products to specific customer needs will become the new cornerstone of intermediaries’ business models.

Matchmaking Using Superior Data

Historically, merchants have risen from poverty to wealth by exploiting facts no one else had. Traders would buy low because they knew who offered what for sale. They would sell high because they knew who wanted what. Arbitrage profit — the difference between buying low and selling high — was the bedrock source of value for go-betweens.

Commercial agents benefit from superior product knowledge, too. Because agents deal daily with goods and services most buyers purchase only on occasion, buyers rely on their knowledge. That not only gives agents opportunities for suggesting additional purchases and generating higher margins, it allows them to extract payments from upstream producers.

The Internet erodes the profit potential of superior data. Both sellers and buyers are only a few clicks away from information about what is wanted and offered in the marketplace. Sellers can use their own Web sites, online communities and trading sites to locate customers, find out what they want and make a pitch. Buyers find it easier to compare pricing and availability, to research producers’ reputations and to equalize local imbalances between supply and demand. Increasingly, business buyers enter bargaining situations knowing as much as the middlemen do. Nevertheless, for both buyers and sellers, information gathering is a lot of work.

Intermediaries that adapt still have something to offer. Problem solving has increased in value in part because electronic networks offer too much information, aggravating search problems. Intermediaries will be remunerated for reducing the morass of data to just what each individual buyer or seller wants to know. RATs are paralyzed by too many choices; go-betweens create value by delivering to each individual the right choices and the right tools for making decisions. They will reap returns from consultative selling to customers who know the results they seek but not how to get there.

Requisitioning Items As Is

Traditionally, merchants also have been paid for helping customers requisition goods and services. Customers expect a requisitioned item to show up at the right time in the right place (time-and-place utility) as part of the right bundle. Consequently, part of the middleman’s margin has reflected provision of those needs.

Unlike a lone supplier, a trader offers customers an assortment. Buyers value the ability to compare and evaluate rival brands in order to create the right bundle. Thus category-killer stores prosper by bringing virtually every choice in a category under one umbrella. Examples include consumer-oriented aggregators such as Staples, which sells office supplies, and the business-oriented BenefitMall.com, which sells insurance products for small businesses.

Merchants also reap arbitrage profits by buying in bulk and selling in small lots. Individual customers generally can’t offer producers enough volume to warrant a discount — although, if customers buy in bulk, retailers like Sam’s Club do give them discounts.

Another source of profit from requisitioning depends on making goods available when and where customers want them. For years, Coca-Cola built a distribution network that, according to its ads, would “put a Coke within reach of anyone with a thirst.” Those entitled to a markup might include intermediaries bringing beverages to parched baseball fans or those keeping inventory handy for bulk customers.

The Internet doesn’t eliminate but does erode traditional sources of intermediary profit. The value of assortment is lower when dozens of Web sites can aggregate anything, facilitate comparison and create bundles. That is also true when metamediaries provide access in one site to all complementary goods and services associated with events such as moving, getting married, buying a home or recovering from a natural disaster.

Suppliers who collect customer data on the Web are pricing goods and services to reflect the lifetime customer relationship, giving better prices to better customers. Under that scenario, the ability of intermediaries to offer lower prices based on economies of scale becomes less significant. Online buying clubs eventually will develop their own economies of scale. Although they have yet to produce a viable business model because they force customers to accept standardized goods and don’t provide an assured purchase at an assured time, that will change.

Other forces, only partially related to the Internet, also erode some intermediaries’ traditional scale advantages: for example, the rise of third-party logistics providers (3PLs), which let suppliers outsource shipping and storage of finished and intermediate goods. Traditional freight forwarders such as Federal Express, DHL Worldwide Express and United Parcel Service have increased efficiency by exploiting today’s computing power, advanced operations-research techniques and new ways to track goods. Further, 3PLs have made massive and risky investments in central warehouses, specialty equipment, cross docking (dedicated warehouses allowing trucking companies to run trucks loaded in both directions for major customers), and elaborate, interlocking sea, air and land routes.

The combination of 3PL services with the Internet’s ability to track goods and support tight supply chain coordination erodes the scale advantages that intermediaries who also did logistics used to enjoy. Any intermediaries that continue to provide logistics services will be held to a higher performance standard and will have to lower their prices.

Profits based on time-and-place utility are also likely to decline. Online purchasing, with many Web sites open around the clock, offers new advantages. If one supplier is out of stock, it’s possible to find another supplier that can ship immediately. Although the Achilles’ heel of e-commerce remains fulfillment, with the ongoing lag between placing an order and having it delivered, for many purchases that is not a deal breaker. Furthermore, the economics of drop-shipping small lots direct to consumers are continually improving, and in cases such as mailed prescription refills, they’re competitive. Hybrid solutions also are evolving: for example, pharmacies that allow customers to order online and pick up orders at a drive-through window. Such trends make customers more resistant to reimbursing merchants for holding inventory.

Fortunately for intermediaries, new ways of exploiting economies of scale, scope, and time and place are emerging —approaches depending less on logistics than on analytics. Consider how collaborative filtering can stimulate extra purchases. Customers agree to rate books, say, on a numerical scale, indicating which ones they’ve liked and which are unfamiliar. The middleman can build a profile of the customer’s preferences, search a database to find other customers with similar tastes — then recommend books that people with matching preferences enjoy.

Collaborative filtering benefits from scope and scale. The greater the number of different goods for which resellers have data, the more they can exploit cross-correlations. For example, Amazon.com found that customer preferences for books and CDs were closely aligned. Knowing what to recommend helped increase sales. The merchant with millions of customer profiles can find the most and the best matches. The key to realizing such advantages is analytical capability, not logistical capability.

The Internet also creates new, intellect-based time-and-place utility. By analyzing patterns of interactions, intelligent sellers can identify opportunities to make the right offer at the right moment. Confronting buyers with a sales proposition that tenders what is sought reduces the customer’s search costs to zero. Most customers will not insist on seeking out a better deal — as long as the proposition is reasonable. The seller has what amounts to a temporal monopoly, a golden opportunity to make an offer. Clever merchants seize that window of time to cross-sell complementary goods, up-sell to the level of quality the customer really needs, and suggest additional goods and services for the perfect augmented product.

For example, WeddingChannel.com simplifies a bewildering event, instructing the wedding planner as to the myriad arrangements needed and how much time to allow for each. Vendors are suggested for such things as flowers, caterers, wedding gowns, event venues, printers and travel providers. A couple can create a Web site that functions as a gift registry. Some information is provided free to build loyalty, perhaps a primer on wedding etiquette. The possibilities for cross-selling and up-selling are vast. Ironically, WeddingChannel.com begins by offering simplification of the wedding yet may inspire the couple to complicate it. And the process need not end with the wedding: The Web site directs newlyweds to another site for beginning married life.

Ensuring Quality, Modifying Offerings

It is not new that intermediaries help suppliers by helping customers solve problems that are holding up a sale. But online commerce has intensified the importance of middlemen because it aggravates those problems. For example, it is harder for a customer using the Web instead of a store to be certain of getting a quality product or to buy something personal without the whole world finding out.

First, consider quality problems. In categories such as consumer electronics, middlemen have long generated profits and customer loyalty from extended warranties and money-back guarantees. But such services are even more critical now that both customers and suppliers are overwhelmed by the Web’s reach. How can suppliers possibly build trusted brands everywhere they can ship? How are customers to know which suppliers to trust? The Web has many fraudulent sites, after all. More than ever, intermediaries can benefit suppliers, customers and themselves by offering goods under their own brands and providing warranties.

A second consideration is anonymity. Part of the value proposition for many intermediaries traditionally has been ensuring clients’ anonymity. Hence investors use brokers to sell stock for them, home buyers employ real estate agents, and some consumers conduct business using only cash.

Unevenly secured e-commerce sites generate additional concern for anonymity and suggest a new opportunity: specialized privacy intermediaries that conduct transactions on behalf of buyers who don’t want their click streams mined for data. Alternatively, such go-betweens could help their customers get discounts in exchange for personal information or for agreeing to receive targeted promotions. Even if privacy intermediation doesn’t become widespread, middlemen will help customers manage the way their data are used.

The third consideration is adaptation of goods and services to create an augmented offering. Traditionally intermediaries handle as-is goods without modifying them. In some industries, however, value-added resellers contribute proprietary shells, peripherals, software or services to a manufacturer’s core platform. To buyers who see the reseller nameplate on the anonymous supplier output, the reseller is the original equipment manufacturer, and it’s the reseller’s brand they value.

As more products and services get connected to the Internet, opportunities to customize and configure them will increase. Manufacturers will provide many services themselves but probably won’t meet idiosyncratic local needs. Middlemen, whose lookout position enables a broader view, will be able to fill the gap. They need not displace manufacturers in adapting output. Services often beget a need for more services. It is likely that producers will provide a fundamental layer of tailoring for individual customers on top of which middlemen will provide other layers.

Transforming the Distribution Landscape

Today’s intermediaries will thrive if they shift the way they add value and get compensated. The nine things intermediaries currently use to create value (data about buyers, data about sellers, data about products; economies of scale, economies of scope, time-and-place utility; quality assurance, anonymity and tailoring of products) will change in varying degrees. It is unlikely any one enterprise can perform all nine functions well. New types of specialists and hybrids will emerge, exploiting the advantages of focus just as third-party logistics providers have.

Smaller entrepreneurial enterprises will move into micro niches that have not heretofore been sustainable, and eventually they will be consolidated into unusual hybrids. Such enterprises will have in common a business model based on the intermediary cycle. (See “The Intermediary Cycle.”) Those that survive will do so by solving a customer’s problem, building proprietary knowledge that allows them to solve producers’ problems, and developing a second store of valuable knowledge (about how producers are perceived and evaluated by different customers).

From the supplier’s point of view, the result will be a much more complex and fragmented mesh of problem solvers. But the mesh will be more efficient than our present distribution systems because members will specialize in solving a wider range of customer and producer problems than we know how to address today. Producers will be better off not going direct to every customer, because this burgeoning network of centrally positioned problem solvers will serve buyers best.

As Web services begin dramatically reducing the cost of assembling a package of services quickly, middlemen will bundle financial services, logistics, complementary goods, training, content and other elements of an augmented, personalized product. Tools are emerging from companies such as Hewlett-Packard and Bowstreet that will allow marketing managers, not information-systems managers, to specify how to handle individual customers. Depending on the customer’s behavior and demographics, a more-or less-expensive, comprehensive offer will be crafted quickly and revised as needed.

Customers will access the bundled solutions without being aware of the complex mesh. They need not know that the vendor who offers the right augmented product has assembled it in real time from assorted providers. As the landscape of middlemen becomes more fragmented and complex, it actually will appear simpler and more linear to the customer.

Some customers may approach transactions with part of a supply chain in hand. Buyers who have already settled on a logistics provider or a source of financing, for example, will find vendors who can snap together the other pieces of the offer around those the customer has preselected.

Calling such a system a service hub rather than a channel could be one of the most fundamental Internet-generated changes. The actor who takes the order and assembles its pieces is in the hub’s center; the outer members provide the services that the assembler assembles. Although the outer members do not sit in the hub’s center, they are middlemen to the extent that their role allows them to solve some of the problems the offer addresses. Rather than standing between the producer and the customer like traditional middlemen, they are complementors to the producer.

What Should Producers Do?

Producers today must decide how thoroughly to embrace interactive marketing. Fearing to disrupt current systems, particularly those that have been a source of competitive differentiation, many stifle Internet initiatives. They do so at their peril because players with different business models and no investment in the status quo will take over. Outsiders can upend an industry by allowing buyers to show how much they really value conventional service.

Consider some examples. In the car industry, CarsDirect.com gives buyers an alternative to dealers. Its principal backer comes from another industry entirely — Michael Dell, of Dell Computers. In Dell’s own industry, personal computers, Trilogy.com allows buyers to configure any computer with complete disregard of brand names. And AuctionWatch.com helps buyers in all industries to procure goods and services through auctions without the cost and effort of monitoring the auctions themselves. Outsiders will force everyone in today’s supply chains to embrace interactive marketing and endure the consequent disruption. Established companies are capable of coopting the Net. New competitors will hurry them up.

Partnering on New Business Models

This is not the time for suppliers to get closer to the customer by disintermediating. Service-hub members are needed to bring a buyer into the market and to get the right items to the right place, at the right time, in the right bundle at low cost — not a trivial challenge. Producers should not cut out middlemen just because the Internet has lowered the cost of going direct. Vertical integration is never justified merely because it is feasible. There must be a strategic reason.4

Suppliers (or any hub member who wants a Web-enabled service-delivery system) should view the old channel relationships as assets, not liabilities, and should support other members as they develop new revenue streams. That might mean assuming more of a hub member’s risk. The Web will push channel systems away from making money on gross margin. With gross margin, I sell to you at price X; you own the inventory and resell it at a markup to make money. In an Internet world, gross margin transfers too much risk downstream. Making resellers work hard to earn a good margin and to minimize inventory-holding costs is no longer so healthy for the overall system.5

The danger of the Internet lies in Web-only sellers and resellers riding free on brick-and-mortar participants. The offline provider collects the costs; the online provider collects the benefits. Off-line intermediaries won’t tolerate indefinitely customers comparing items in stores, then buying from someone else online. Intermediaries will drop a supplier who helps a buyer use the Web to bypass them. But they can’t drop everyone, so how are they to avoid victimization?

Free Ride Versus Vertical Integration

One solution is vertical integration: costs and benefits united in one organization. Suppliers might integrate forward into distribution and bear the costs as well as the benefits. Alternatively, resellers might use private labels and integrate backward into production to prevent free rides.

Some catalog companies already have vertical integration, operating both physical sites and catalogs. The customer uses the catalog for free rides on the store. But strategies that suit the customer pay off for the marketer. Catalogs and stores expand one another’s business. Indeed, some companies serve a geographic area by catalog as a test, then open a store when the area passes a volume threshold. The store often boosts catalog sales in return.

E-commerce can work that way, too. JC Penney has found that customers who shop its Web site heavily also shop its stores heavily. The Web site and physical shopping facilities appear to be complementary.6

Free Ride Versus Compensation

Unfortunately, vertical integration is seldom the most efficient or effective solution to victimization of middlemen. If all parties care about offering customers the convenience of the Web plus the benefits of a physical site — and they should — a better solution to the free-riding problem is compensation. The party that enables free riding (the supplier) should compensate the victim (dealer or department store). For example, a fashion supplier with an interest in being seen in department stores should compensate the store for customers who look, try on, but then order online from a cheaper source. The fashion house should share with the department store its Web revenue from all sources, acknowledging that the store generates some of it.

One approach is for the supplier to pay a service-hub member an override, which is a portion of the supplier’s Web-based revenue. The more the supplier sells on the Web, the more the department store or relevant partner makes. That adapts a time-honored way of resolving disputes among commission-based salespeople when a customer consults with one but places the order with another.

A second way to compensate victims is to take on some of their risk. The supplier might pay slotting fees or fixed-trade allowances. The former are fixed sums the supplier pays the retailer in return for carrying the merchandise — literally renting a slot on a shelf. The latter are lump sums the supplier pays the retailer in return for performing specified functions, such as advertising. Another option is to shoulder certain expenses, as European suppliers do when they contribute to the cost of a store’s renovation.

A third approach to compensation is to recommend the partner’s services. When manufacturers sell direct, they might pass the customer over to another hub member for complementary and ancillary offerings. For example, if Ford as supplier uses the Web to sell a car direct to a customer, it could steer the customer to a local Ford dealer for detailing, undercoating and service.

Ethan Allen, a maker of upscale furniture, has quasi-independent stores, and whenever the manufacturer makes a sale on the Web, the nearest retailer automatically receives a 10% override. The override becomes 25% if the retailer assists the sale with, say, delivery, on-the-spot repairs or returns. The Web site also might encourage those who surf there to visit the local store for ancillary services such as interior decoration.

Working With Many Partners

Providing compensation isn’t charity, it’s mutual interest. Rewards are conditioned on cooperation. Overrides can be linked in part to suggestions that generate greater sales or to the overall usefulness of information that an intermediary supplies. Overrides also might be tied to participation in promotional programs that benefit an entire service hub. Incentives for partners should not be considered subsidies. They are tools that may be useful in the context of a cooperative relationship.

The Web forces companies to recognize that no single organization can do everything. Customers will not become RATs, but they will insist on freedom of choice. And because their reasons to buy — price, assortment, service, convenience, ambiance — will vary and no single service provider can do everything, service-hub participants must join forces.

That means multiple constellations of providers and different cross-selling bundles. In Web-enabled commerce, entirely new types of partnerships are feasible. Everyone must experiment. Even players that own the customer will need ancillary services. It is unlikely that one giant enterprise, totally integrated, will emerge to sit close to the customer.

What Should Customers and Intermediaries Do?

Message to intermediaries: Transform or wither. Transformation requires co-opting the Net, embracing collaborative filtering, seeking occasions to build temporal monopolies, creating tailored services, improving quality and protecting privacy. Instead of charging for information, companies should understand that data provision is becoming a cost center, except for products that involve consultative selling, idiosyncratic buyers and sellers, or demonstration. Intermediaries must be open to new ways of doing business with suppliers. They should not demand exclusive deals or insist that suppliers eschew the Web. They must permit suppliers to work with multiple middlemen. However, they should require that suppliers share risk and compensate for free rides.

For customers, the new environment doesn’t mean dumping third-party providers of distribution services. Going directly to the supplier doesn’t necessarily equal better service, price and priority. Intermediaries provide value. And those suppliers who appear to offer output direct from the factory really may be improvising a service hub of third parties to meet buyers’ needs.

The assumption that the Net would allow suppliers to reach customers by a more direct route was based on an incomplete understanding of distribution. The Web transforms but does not eliminate the advantages of the central lookout position. Certainly, intermediaries will change. They will be forced to, but they’ll survive. It is comical to recall how salespeople of the early 1980s dreaded the fax machine’s potential to take customers directly to accounts receivable and the factory floor. Ultimately salespeople co-opted the fax, and in the same way, intermediaries will co-opt the Net.

With appropriate, fair incentives and proper hub management, there will be enough trust to permit producers to get closer to customers after all. Intermediaries’ central position and value-added services will continue to solve customer problems and hence will solve producers’ problems too. Distribution strategy will continue to involve using any means, from any player, to lower barriers blocking transactions. That is what generates gains to trade. That is how the Web will help companies get closer to customers — indirectly.

References

1. R. Cox and C.S. Goodman, “Marketing of Housebuilding Materials,” Journal of Marketing 21 (July 1956): 36–61.

2. A.T. Coughlan, E. Anderson, L.W. Stern and A.I. El-Ansary, “Marketing Channels,” 6th ed. (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2001), 88–99.

3. Anonymous, “To Have and To Hold,” The Economist, June 16, 2001, 9–11.

4. For a review of those reasons, see J.B. Quinn and F.G. Hilmer, “Strategic Outsourcing,” Sloan Management Review 35 (summer 1994): 43–55.

5. For more on replacing gross margins with fees for service, see A.J. Fein, “Facing the Forces of Change: Future Scenarios for Wholesale Distribution” (Washington, D.C.: National Association of Wholesaler-Distributors, 2001).

6. S. Buel, “Searching for the Retail Trifecta,” The Industry Standard 6 (October 2000): 108–116.

Comment (1)

idehpardazi tabnak