Outsourcing Business Processes for Innovation

Many companies look to business-process outsourcing to save money. But the most successful clients concentrate less on cost savings and more on achieving innovation.

In recent years, the number of companies that outsource critical business processes to outside suppliers has grown significantly worldwide. The business-process outsourcing (BPO) market has been estimated to be worth $309 billion in 2012,1 including activities such as finance and accounting, human resource management, procurement and legal services, and the overall volume is estimated to be growing at a rate of around 25% annually.2 Many organizations initiated BPO as part of an operational effort (for example, to reduce costs or access skills), but it has evolved into much more. Senior managers today expect more from BPO service providers than short-term cost savings and meeting minimum contractual requirements.3 Moreover, they are skeptical of big-bang improvements.4 Companies want service providers to innovate constantly. (See “About the Research.”) In relationships that companies classify as high performing, the service providers perform a series of innovation projects that deliver substantial long-term improvements to the client’s operating efficiency, business-process effectiveness and strategic performance. Consider the following examples:

- A BPO provider helped a health care company improve the claims adjudication process by using analytics to predict claims likely to result in rework. The predictive tool now intercepts more than 50% of claims that would have been reworked, saving the client $25 to $50 in administrative costs per overpaid claim and $6 to $12 per underpaid claim.

- An aerospace manufacturer worked with its BPO provider to add new key performance indicators and processes to manage third-party vendors. This allowed the client to improve customer-order fill rates for new parts from 60% to 85% and turnaround times for delivering parts to grounded vehicles from 21 hours to 17 hours.

- A supermarket chain collaborated successfully with its BPO provider to implement new forecasting tools, techniques and methods that improved the client’s stock fill rate from 80% to 95%, reduced inventory by 27% and reduced error rates by 50%.

These types of innovations are not automatic. Companies and service providers must work together to foster innovation. Specifically, companies must motivate providers with incentives, and both parties must nurture a collaborative culture that produces continuous waves of innovations within client organizations, something we call “dynamic innovation.” For example, the supermarket chain cited above worked with its BPO provider to complete a series of more than 50 continuous improvement projects over the course of three years to achieve cost savings, faster product delivery times and higher fulfillment rates. A static view of BPO innovation would treat each individual innovation as incremental; a dynamic view looks at how year-on-year programs accumulate to improve the client’s overall performance.

What do BPO professionals mean when they talk about innovation? Based on interviews with clients and providers, innovation is generally defined as any activity that improves the client’s performance. For example, one client defined innovation as “realizing there is a different and better way of doing something, and combining this with the ability to deliver.” Our survey of outsourcing professionals found the same result.5 The most widely accepted definition of innovation by clients, providers and advisors was “something that improves the customer’s services or costs, regardless of its novelty.”

One of the most promising lessons from our research is that it is never too late to start innovating. Many high-performing BPO relationships did not enact contractual innovation clauses until well after the relationship had been established. Other high performers did not include innovation in the original contract, but added incentives for innovation a few years into the relationship.

Incentivizing Innovation

BPO providers do not need incentives to develop innovations to improve their own revenue or margins, but they do need them in order to focus on the client’s performance. We found that both clients and BPO providers identified several measures such as mandatory productivity targets, innovation days and gain sharing at the project level as the most effective incentives for innovation. Other approaches to incentivizing innovation include making sure that providers know that they don’t have a lock on the business and introducing special governance provisions, such as committees dedicated specifically to innovation.

Mandate yearly productivity improvements.

Many BPO relationships are still priced based on resource inputs, such as the number of full-time equivalent employees required to perform the services. Although companies like the simplicity and predictability of FTE pricing, they recognize that input-based pricing can discourage providers from innovating out of fear that it will mean reduced revenues. To overcome this disincentive, many BPO clients have introduced provisions that require service providers to improve the client’s productivity by 4% to 5% per year. Both clients and providers have endorsed this approach. For example, a human resources firm developed several innovations, including a new dashboard that allows the client to monitor customer satisfaction in ways that allow managers to identify specific problems. The client explained, “If a measure of client satisfaction was off the key service indicator, we could actually dive down and see what part of the business it was coming from.” The service provider notes that the innovation was prompted by the client’s demand for continuous improvement and did not result in additional cost to the client.

Companies and BPO providers that built business cases for each innovation project and agreed in advance how the financial compensation would be allocated reported good results with gain sharing.

Reserve time to drive the innovation agenda.

Innovation objectives can slide down the priority list when people are focused on operations. But in high-performing BPO relationships, interest in innovation doesn’t fade; companies and BPO providers contractually dedicate time each year to drive the innovation agenda. The contractual clauses are different in each relationship, but in each case they define the innovation agenda for the coming year (specifying, for example, innovation days or innovation forums). For example, one service provider holds an innovation forum at least once a quarter with her clients. “We bring what we see in the market, and the client brings what they are seeing in their market,” she said. Based on this interchange, the provider and client figure out what the continuous improvement agenda for the next quarter should be. Another provider explained how his company works with clients: “We have our basic operational plan for any given year, and on top of that we ask: What additional value in innovation can we bring? We develop an innovation plan that focuses on at least four to six key value innovations.” From this process, the partners developed an innovation agenda that involved moving 40% of the training courses online, including mobile learning capabilities through smartphones.

Gain share the benefits from specific innovation projects.

Among the different ways to incentivize innovation, gain sharing packs the most punch: It promises to improve a company’s performance while also increasing the service provider’s revenue. In our innovation survey, 79% of clients, 77% of BPO providers and 78% of outsourcing advisors saw gain sharing of innovation benefits as the best way to drive innovation. Surprisingly, however, survey respondents reported that only 40% of innovations delivered used gain sharing. Our interviews also found fewer than half the clients contracting for gain-sharing clauses; even when gain sharing was included in the contract, only half of the clients took advantage of the gain-sharing option. Still, 25% of the interviewees said that gain sharing was responsible for powerful innovations within their organizations.

It’s worth noting that gain sharing tended to work better in some settings than others. It was most effective when used at the project level. Companies and BPO providers that built business cases for each innovation project and agreed in advance how the financial compensation would be allocated reported good results with gain sharing. By contrast, those that contracted based on overall provider performance on a yearly basis reported poor or mixed results.

One of the best examples we found of project-level gain sharing was at Microsoft,6 which contracts for global financial and accounting services with Accenture. The two companies agree to a gain-share allocation in advance for each innovation project. Specifically, they agree on how much Microsoft’s bill will be reduced and how much Accenture’s profit margin will increase. Microsoft might offer to double Accenture’s profit for a particular service if Accenture is able to reduce its services bill by a certain amount. The overall effect is the creation of strong incentives for Accenture, as described by the provider’s executive for the Microsoft relationship: “My client recognizes that I need to meet my financial commitments as the service provider. That may sound strange, but there is a realization that, fundamentally, I have to be incentivized to do some of the things I need to do. The key message is a spirit of partnership that I don’t think exists in the other engagements that I’ve come across.”

Leverage the threat of competition to incentivize providers.

Several BPO providers in our study felt pressure to innovate for clients based on fear of competition. Although the particular contract did not specify anything about the need to innovate, one service provider noted, “In my mind, if we don’t innovate, at the time of contract renewal the client will take this business somewhere else if we can’t prove that we are delivering value beyond transactions.” Providers see innovations as a way to differentiate their services in a highly competitive market. As one said, “It is part of the value added that we bring. We are constantly challenging ourselves to step up our game to improve all the time and adding value to the client’s business. In doing so, we are also creating some offerings that are very different than conventional BPO.”

Use governance to incentivize innovation within organizations.

Large BPO relationships are typically governed by operating committees focused on day-to-day operations, management committees focused on monthly invoices and service-level reports and steering committees comprised of senior executives who meet annually (unless there is a dispute). However, 60% of BPO clients responding to our survey said that innovation calls for special governance provisions beyond these existing committees. Only 42% of providers agreed. Based on our interviews, we found that the people selected to lead are more important than the structures erected to govern.

According to our survey and interviews, other types of incentives were not as effective. The least effective incentives were innovation funds, benchmarking and gain sharing/pain sharing at the relationship level. Innovation funds — special accounts set up to fund future innovation projects — were recommended by just 38% of clients, 30% of providers and 33% of advisors. These relatively low percentages may reflect the fact that the funds are often too small to motivate parties.7 Benchmarking of best-in-breed prices and service levels, meantime, is intended to incentivize providers to increase performance to the level of competitors. But benchmarks often end up triggering disputes. For example, when an external benchmark found that the provider’s unit price was well above the best-in-breed price, the client asked for a reduced price. The provider claimed the comparison was unfair because the provider had been asked to maintain the client’s old technology rather than shifting to a newer, more efficient technology. Clients who defined gain sharing or pain sharing at the relationship level claimed that annual performance targets were set too low. One client explained: “The standards were a bit one-sided and not difficult to meet. It ensured that each year there was a good bit of gain, and the gain went to the provider. We lose the notion of pain/gain.” To receive benefits from gain sharing, “you should be truly delivering something fairly extraordinary,” the client added.

Delivering Innovation

While partners may incentivize innovation by using mechanisms such as productivity targets, allocating innovation days and agreeing to gain share on innovation projects, innovation won’t happen unless clients and providers implement a more comprehensive process. The process should combine acculturation across different organizations, an engaging method for generating ideas, adequate funding and a system for managing change.

Acculturation

In BPO, relationships extend beyond the client and provider teams in charge of the account. In many instances, multiple organizations and parts of organizations take part, including the client’s centralized business services organization that “owns” the BPO relationship, the client’s decentralized business units that receive BPO services, the provider’s centralized organization that sells BPO services and allocates resources to accounts and the provider’s globally dispersed service delivery centers, which may operate remotely in other countries. What’s more, each organization tends to want different things. The client’s centralized business services organization often wants tight cost controls, high productivity and process standardization. The client’s decentralized user communities chafe at controls — they want responsive, flexible and customized services. The provider’s centralized culture is looking to generate growth, while the globally dispersed delivery teams want to please both their supervisors and customers, which can leave them caught between conflicting cultures. Merged cultures often end up borrowing aspects of both the client’s and the provider’s cultures. In several BPO relationships we studied, the partners went so far as to brand the provider’s delivery centers with the client’s company colors, logos and office layouts. For their part, clients recognized the special holidays and festivals in the provider’s culture.

In the context of dynamic innovation, the culture must be transparent so that even remotely located provider employees understand how their work contributes to the client’s performance. One provider explained: “When someone is sitting in a place miles away, it is really important for that person to understand the impact of what he or she is doing to the client organization. As soon as you are able, get that culture in offshore delivery locations, or even onshore delivery locations, so they can relate to what kind of impact they are bringing to the client. I think it makes a huge difference in performance.” The culture must also encourage, welcome and reward innovation ideas.

Idea Generation

We asked innovation survey respondents to identify the primary source for innovation ideas. Clients, service providers and advisors all agreed that the majority of innovation ideas were either jointly developed between clients and providers (as described by the innovation days practice above and in our previous work on collaborative innovation8) or by providers generating innovation ideas on their own.

In high-performing BPO relationships, leaders actively encourage all levels in the provider organization to challenge the status quo, to question assumptions and to identify innovations that will improve the client’s performance. For example, one executive and the employees of his remotely located BPO have monthly meetings to air ideas9 and reward continuous improvement and innovation. The provider’s employees are encouraged to identify problems and challenge the client. “We absolutely want [them] to point some of those things out,” the executive said. “We have tried to make that positive. It’s generated lots of good ideas that we’ve been able to put into practice.” The provider’s employees know that their ideas will be heard, vetted and recognized.10

Services providers can be well positioned to see opportunities for innovation. Those that deliver services on a regular basis can track ideas across a global client network and spot BPO trends quickly. For example, an electronic design company was impressed with its BPO provider’s ability to innovate based on its purchasing expertise. In addition to being able to use its knowledge of the supply chain and category expertise to save money, the provider has the ability to attract and retain top talent better than the company could on its own.

Funding Support

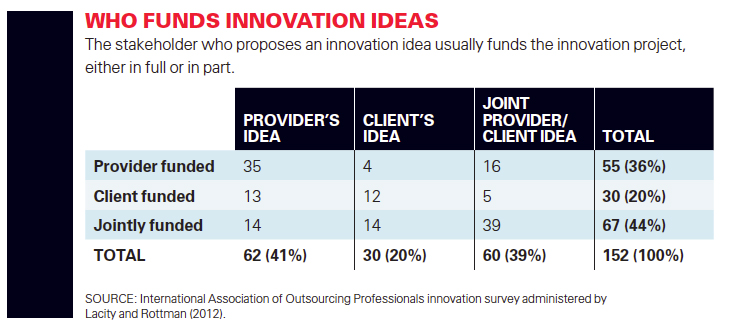

As we learned from the gain-sharing incentive, BPO innovations are most successful when they are funded as projects, each with a sound business case. But who foots the bill for process innovations? In our innovation survey, we found that 44% of the innovations were jointly funded, 36% were provider funded and 20% were funded by the client. Removing advisors from the data, we compared responses about funding to responses about the source of the idea. We found that stakeholders who propose innovations usually help fund their implementation. (See “Who Funds Innovation Ideas.”) This suggests that people tend to pitch innovation ideas that they themselves stand to benefit by and are therefore willing to finance the projects in whole or in part.

Who Funds Innovation Ideas

Change Management

Clients from high-performing BPO relationships understand that they cannot be passive recipients of innovation. They must aggressively manage the change that innovation brings to their organizations. In other words, provider incentives lay the foundation for dynamic innovation, but the execution of dynamic innovation requires strong commitment to change management in order to transition individuals, teams and organizational units from the current state to the desired future state. Innovations must be accepted by two groups of clients — the client’s centralized business services organization responsible for the BPO relationship and the globally dispersed end users. Sometimes the client leaders resist innovation ideas because they lack the energy or resources to lead the change management effort required or because they have other priorities. One client told us, “For some of the provider’s ideas they’ve brought to us, we’ve said, ‘Thanks for telling us, but actually we’re not prepared to make the change.’” If the client leaders are excited about innovation and the leaders are respected within their own organizations, they are usually successful in their change management efforts. On the other hand, if the client often rejects ideas, the risk is that the provider will stop investing time and resources in identifying innovations. A provider in a high-performing BPO relationship says of his client lead: “He knows the business very well. He knows how relationships work, and he’s politically savvy.”

Having the Right Team

Many BPO relationships need to work on incentivizing, contracting for and delivering innovation. We found that the most significant factor in BPO innovation is whether the right people are in place to drive the dynamic innovation process. An effective leadership pair — one person from the client organization and another person from the provider organization — goes a long way toward invigorating the innovation process. Selecting the proper leaders is critical. In the high-performing BPO relationships we looked at, the leaders were experienced and capable and had high levels of credibility, clout and power within their own organizations. Effective leadership pairs enjoyed working together, which some research participants described as “chemistry.” They displayed the following behaviors:

- A focus on the future: The leadership pair focused on where they wanted the BPO relationship to go, not where the relationship was or where it had been.

- A focus on client outcomes: The leadership pair always did what was best for the client organization and then settled a commercially equitable agreement.

- A spirit of togetherness: The leadership pair often disagreed behind closed doors, but they presented a united front to stakeholders in their respective organizations.

- Transparency: The leadership pair was open and honest about all operational issues.

- Orientation toward problem solving: The leadership pair sought to diagnose and fix problems; they did not seek to assign blame.

- Orientation toward action: The leadership pair was not afraid to expend their powers; leaders acted swiftly to remove or work around obstructions to innovation stemming from people, processes or contracts.

Perhaps as a consequence of these behaviors, both leaders in these pairs displayed an optimal level of trust.11 Each felt secure and confident in the other person’s good will, intentions and competency.

In several cases, we found client-provider pairs in which both parties were experienced leaders but the combination simply did not work. Changing one of the leaders (or both, if necessary) can improve performance.12 For example, the client leader in one high-performing BPO relationship based in Europe told us that he had requested that the provider assign a different account manager when he could not work effectively with the original person; the provider granted the request. The client leader contrasted the two account managers: The first account manager “was a more senior guy with the attitude, ‘Well, I’ve done it, I’ve got the T-shirt, I know what I’m doing, I don’t know why you’re panicking, leave me alone to get on with it.’ He may have been a very good chap, but I couldn’t work with him.” The second account manager “was actually more junior but was somebody with whom we could work.”

BPO relationships that were performing poorly at first were transformed into good or even great BPO performers under new leadership pairs. The leaders were able to foster dynamic innovation by creating strong incentives. Even when contracts did not initially include innovation incentives, we found that several high-performance organizations added incentives after the BPO relationships stabilized. For example, one company required its BPO to demonstrate productivity gains year-on-year. However, the provider had no incentive to go beyond those levels. To maintain pressure, the client recently negotiated for a gain-sharing model in which the provider was rewarded for anything that went beyond the required percent of productivity. The client also stands to benefit. As the client explained, “We made it a joint-productivity gain initiative, so there is also reward and recognition for our own people when we go beyond the threshold.”

Effective innovators recognize that creating incentives can only take you so far. Delivering innovations requires participants to break habits, change their ways of doing things and mandate innovation. There’s a saying that if you always do what you always did, you will always get what you always got. Rather than being hemmed in by traditional modes of operation, companies and service providers have an opportunity to unlock value by working together to achieve dynamic innovations.

References (12)

1. J. Harris, K. Hale, R.H. Brown, A. Young and C. Morikawa, “Outsourcing Worldwide: Forecast Database,” September 13, 2010, www.gartner.com.

2. V. Couto and A. Divaran, “Outsourcing for Virtuosos: How to Master the Art of Global Enterprise” (Booz & Co. webinar, Dec. 6, 2006); and M. Lacity and L. Willcocks, “Advanced Outsourcing Practice: Rethinking ITO, BPO and Cloud Services” (London: Palgrave, 2012).

View Exhibit

View Exhibit

Comments (10)

Biju Peter

Robert Smith

James Bishop

Ryan Davidson

Manish Salwan

Eli Stutz

Cha Wi

Alleli Aspili

Jennifer Bach

Joe Tillman