Sustainability: The ‘Embracers’ Seize Advantage

Preface & Summary

A Sweet Spot on the Adoption Curve?

While global economic and political factors might have predicted otherwise, corporate commitments to sustainability-driven management are strengthening.

But even as enterprises overall are strengthening their commitments, one cohort of organizations is expanding its commitments far more aggressively than others — and a gap has emerged between sustainability strategy leaders (“embracers”) and laggards (“cautious adopters”).

Those are among the key findings yielded by the second annual Sustainability & Innovation survey of global corporate leaders — a collaborative study by The Boston Consulting Group and MIT Sloan Management Review. How are organizations responding to the challenges and opportunities of sustainability? How are the terms of competition shifting — or not shifting — in the face of sustainability concerns? How is cutting-edge management practice being transformed as a consequence? Those are the questions explored in this study, through both the global survey and a series of in-depth research interviews with thought leaders and business executives. This report contains the study’s results.

The discovery of broad-based growth in sustainability-related investments is explained in part by further findings that companies increasingly believe sustainability will become a source of advantage, should be incorporated strategically in all aspects of a business’s operations and eventually will require a sea change in competitive behavior. “We need to integrate sustainability, not as a layer, but in the fabric of the business,” argues Katie Harper, manager, sustainable supply chains at Sears Canada, voicing a common view.

“The only way to continue growing and continue being a successful business is to treat sustainability as a key business lever in the same way that you treat marketing, finance, culture, HR or supply chain,” says Santiago Gowland, vice president of brand and global corporate responsibility at Unilever. “So really it’s core to the ability of the business to grow.”

While the survey revealed that most companies view sustainability as eventually becoming “core,” what’s more interesting is the revelation that one camp of businesses — the embracers — is acting on the belief that it is core already. Whereas cautious adopters see the sustainability business case in terms of risk management and efficiency gains, embracer companies see the payoff of sustainability-driven management largely in intangible advantages, process improvements, the ability to innovate and, critically, in the opportunity to grow. And the embracers, it turns out, are the highest performing businesses in the study.

Who are the embracers? What do they do differently? By tracking what the embracer companies are doing that stands out from the actions of more cautious adopters — and how those strategies are paying off — this report paints a picture of what management may look like in a world increasingly driven by the sustainability agenda.

Executive Summary

- Sustainability spending has survived the downturn, with almost 60% of companies saying that their investments increased in 2010.

- Companies are committing to sustainability but investment levels vary, with companies dividing into embracers and cautious adopters.

- Embracer companies are implementing sustainability-driven strategies widely in their organizations and have largely succeeded in making robust business cases for their investments.

- All companies — both embracers and cautious adopters — see the benefits of strategies such as improved resource efficiency and waste management.

- All companies recognize the brand-building benefits of developing a reputation for being sustainability-driven. This benefit was rated greatest by all respondents (including both embracers and cautious adopters).

- While even embracer companies still struggle to measure financially the more intangible business benefits of sustainability strategies (such as employee engagement, innovation and stakeholder appeal), these companies are nevertheless assigning value to intangible factors when forming strategies and making decisions.

- Companies across all industries agree that acting on sustainability is essential to remaining competitive.

- Embracers are more aggressive in their sustainability spending, but the cautious adopters are catching up and increasing their commitments at a faster rate than the embracers. They plan to increase their investments by 24% in 2011, while the commitments of embracers (already high) remain static.

- The sustainability-driven management approaches of embracer companies — which claim to be gaining competitive advantage via sustainability — exhibit seven shared traits that together suggest how sustainability may alter management practice for all successful companies in the future.

Business Is Investing More in Competing on Sustainability

The Surprising Downturn Response

While many wondered whether the economic downturn would push sustainability off the corporate agenda, our survey results indicate that the exact opposite is true. In fact, a growing number of companies are now increasing their investments in sustainability. While in our first annual survey, conducted in 2009, only 25% of respondents said they were increasing their commitment to sustainability, in the 2010 survey some 59% said this was the case. “Unlike in previous downturns and recessions, people haven’t necessarily put sustainability on the back burner,” says Nick Robins, head of Climate Changes Center of Excellence at HSBC.

The numbers become even more striking when companies look ahead. Almost 70% expect their organization to step up its investment in and management of sustainability over the next year. Moreover, our survey shows that enthusiasm for sustainability is growing across all industries, particularly in commodities, chemicals, consumer products, industrial goods and machinery retail companies, as well as conglomerates.

Such enthusiasm appears to have survived not only the downturn but also the distinct lack of progress toward international agreement on how to combat climate change. Given Climategate and the failure of Copenhagen, many expected that corporate interest in and commitment to sustainability would decline, but companies continue to launch new sustainability programs every day.

Hal Hamilton, who co-directs the global Sustainable Food Lab with support from Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, sees the downturn as prompting an even broader shift. “The ways of doing business that we’ve accepted are up for grabs,” he says. “We’ll all, inevitably, be thinking more about resilience — resilience to all sorts of shocks. And I rather like the word ‘resilience’ — sometimes it’s better than the word ‘sustainability.’”

The Universal First Moves — Waste Reduction and Resource Efficiencies

In some ways, sustainability is a repackaging of more traditional approaches to lean manufacturing and running an efficient organization. “In this type of economic environment, we are seeing the greatest opportunity in identifying opportunities for resource and cost efficiency,” says Roberta Bowman, senior vice president and chief sustainability officer for Duke Energy. And Bowman’s view is echoed by respondents to our survey, in which waste reduction and energy efficiency emerge as the top priorities, with respondents citing improved efficiency and reduced waste as the activities their organizations currently engage in most frequently.

In fact, this “low-hanging fruit” is often used to make the initial business case for implementing sustainability strategies. For Clorox, it was an entry point into sustainability. “We had done the measurement on footprint and the groundwork on projects so that people could buy into the greenhouse gas reduction, solid waste reduction and water reduction goals,” says Beth Springer, executive vice president of international and personal care at Clorox. “They could see the path.”

For Johnson & Johnson, resource management is also an efficiency measure that contributes to profitability. According to its 2009 Sustainability Report, between 2005 and 2009, the company completed more than 60 energy-reduction projects, representing $187 million in capital investments, which it expects will collectively reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 129,000 metric tons annually and provide an internal rate of return of almost 19%. The projects have so far generated about 247,000 megawatt hours of cumulative energy savings a year.

During the same period, Johnson & Johnson made a 32% cut in both hazardous and nonhazardous waste. “It’s been better for the bottom line, especially in terms of energy costs,” says Al Iannuzzi, senior director of worldwide health and safety at Johnson & Johnson. “Waste is cost to the corporation … and, of course, the less waste you send out of your gates, the less expensive it is to make your product.”

Companies are also recognizing the benefits of driving resource efficiencies outside their own four walls and into those of their suppliers. Over the next five years, Walmart Canada expects to save somewhere in the range of $140 million just through waste and energy and package reduction. “It is very good for business to drive waste out of the supply chain, and over the next five years just in the Canadian operation alone, we estimate we will save somewhere in the range of $140 million just through waste and energy and package reduction,” says Andrew Pelletier, vice president of corporate affairs and sustainability.

Resource efficiency can move downstream into consumer behavior, as well as upstream into third-party producers’ operations. Unilever, for example, is producing laundry products that use less water in rinsing, generating considerable water savings for the people to whom it sells its products. Procter & Gamble also subscribes to similar logic. “One statistic demonstrates to us why this is the path to go, and this is the data that shows that if we got everybody in the United States to switch to cold water [for their laundry], we would prevent the release of 34 million tons of carbon dioxide, which is 7% to 8% of the U.S.’s Kyoto target,” says Len Sauers, vice president of global sustainability at Procter & Gamble, which has developed cold water cleaning technologies. “So, a meaningful improvement targeted at mainstream consumers is really the angle we wanted to take with strategy we set.”

Embracers and Cautious Adopters: Two Views of the Business Case

However, while resource efficiency is a good way to start out on a sustainability strategy, our report reveals a striking difference between two groups of companies in how they are incorporating sustainability into their business operations — those whose activities are limited to short-term, strictly measurable investments such as resource efficiency and those that say they have established a business case for sustainability, have put it permanently on their agenda and maintain that it is necessary to remain competitive.

The philosophies, commitments, strategies and actions of these two broad groups of companies — those that have embraced sustainability (the embracers) and those that have not (the cautious adopters) — differ on many points. More embracers, for example, tend to have recognized the potential for sustainability strategies to deliver new customers for their goods and services as well as to increase their market share and profit margins in existing markets.

And when it comes to views on the relationship between sustainability and competitiveness, the views of the embracers diverge even more markedly from those of cautious adopters, with a far larger proportion of embracers seeing sustainability strategies as a means of gaining competitive edge than cautious adopters.

Of course, being an embracer need not mean that a company is embracing every aspect of sustainability. Depending on their sector and business activities, companies can be embracers and drive the agenda of individual topics within sustainability.

Moreover, views differed among senior leaders when we asked them about the challenges of making the business case for sustainability. “Nobody’s asked me to talk about the business case for several years,” says Peter White, director of global sustainability at P&G. “From our point of view, it’s a done deal — it’s proven, let’s get on with it.”

By contrast, Kim Jordan, founder of New Belgium Brewing, points out that things such as “intellectual curiosity and collective community enthusiasm” are hard to value in monetary terms. “Even more difficult is the consumer side of this because consumers say, ‘This is really important to me,’ but when push comes to shove, when they’re standing at the beer aisle, there are a lot of things that come into play.”

Yet Jordan’s comment, while underscoring the difficulties of monetizing sustainability and measuring it in financial terms, also reveals another important trait that distinguishes the embracers from the cautious adopters. While all companies struggle with quantifying the return on their sustainability investments, in the case of the embracers, this does not dampen their enthusiasm. And while embracers are working to develop the kind of quantification practices that will help link their sustainability activities to the bottom line, they also demonstrate a characteristic not seen among cautious adopters — the readiness to take a leap of faith.

Besides being distinguished by their approach to sustainability, the embracers are also distinguished from the cautious adopters by structural characteristics such as size and sector. For a start, embracers tend to be found among large global or regional companies. According to our data, only 9% of the small companies (with fewer than 1,000 employees) that responded to our survey are embracers, for instance. Meanwhile, 34% of the companies with workforces of more than 10,000 are embracers.

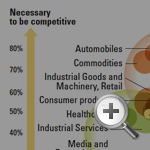

In addition, embracers tend to be part of resource-intensive industries. While our survey found 23% of embracers operating within the service sector, it found a higher proportion (30%) in the product industry sector, where it is more common to find companies that see sustainability as necessary to be competitive and have developed a business case for pursuing sustainability. Product industry embracers focus more closely on efficiency and regulations, care more about the environment and are nearly 25% more likely to consider intangibles in their sustainability-related investments.

FIGURE 4

Respondents who consider themselves sustainability experts are almost four times more likely to have developed a business case than those who call themselves novices.

That is perhaps unsurprising since heavy industries have larger environmental footprints than sectors such as media, technology, financial services and health care. Heavy industries must also tackle a business risk not faced by service industry companies, and that is the risk of losing their license to operate (or being unable to win a contract in the first place). And for companies in sectors such as mining, auto manufacturing and oil and gas, investments are substantial and they cannot pick up and move elsewhere.

That means they have to think long term and adhere to a broader definition of sustainability than some companies, paying attention to human and worker rights and community health and security. “For us, this is a key part of the business driver behind sustainable development,” says Tom Albanese, CEO of Rio Tinto. “It is the license for our asset base to operate.” Klaus Kleinfeld, CEO of Alcoa, agrees. Integrating sustainability into the company’s philosophy and operations is, as he has stated in Alcoa’s 2009 sustainability report, about “earning our license to operate each and every day.”

Long-term thinking is also something embraced by privately held companies. Consider New Belgium Brewing. It has invested in a water treatment plant, which has an anaerobic digester and a combined heat and power plant that recovers energy and methane and converts it into electrical energy. “It is not a two- to three-year payback,” says Jordan. “It’s an eight- to 12-year payback, depending on what happens to waste water plant investment fees and a whole list of costs.”

Who Are the Embracers?

Embracers Are Top Performers

If sustainability embracers tend to be larger, in heavier industries and in growing markets, these are not the only characteristics they share. Critically, embracers not only claim that sustainability strategies are necessary to be competitive — they also believe these strategies are helping them to gain competitive advantage. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of these companies see themselves as outperforming their competitors, with 70% of respondents stating this to be the case, compared with only slightly more than half (53%) of the cautious adopters. Moreover, a larger number of cautious adopters lack confidence about their competitive position. Some 14% told us that they were underperforming relative to industry peers — more than double the number of embracers that see their business in this light.

Embracers are also confidently making the link between sustainability and profitability. Part of this is the ability to increase sales by providing new products valued by consumers who care about issues such as ethical supply chains and energy efficiency. P&G’s director of global sustainability Peter White sees these as including “products that allow consumers to save energy and save money, products that have clear social sustainability benefits in terms of saving people time, empowering women and so on.” Developing these products, he argues, is a way “to actually build your business.”

In some cases, the downturn has even offered companies an opportunity to sharpen their focus on areas in which sustainability can deliver competitive edge. “In the economically challenging environment that we’re in, there is really no room for activities that are not core to the business,” says Duke Energy’s Bowman. “So we have had to do some triage of our corporate services and corporate programs and separate those that are nice to do from those that are necessary to do. That has given us an opportunity to really showcase the business value of sustainability … on many different levels — everything from reputation to new products and services.”

Duke Energy is not alone. Embracers are in fact three times as likely to believe that their sustainability decisions have been profitable. While almost the same number of embracers and cautious adopters believe they are losing money on their sustainability investments, some 66% of the embracers say their organization’s sustainability-related actions or decisions have increased their profits, compared with only 23% of cautious adopters that believe this to be the case.

FOCUS: For Growing Companies in Growth Markets, Sustainability Investments Come Easily

For companies that are in the process of growing, spending on sustainability makes sense, since the required investments — which might be seen as a burden to low-growth businesses — are easier for expanding companies to justify. “Companies with rapid growth are placing sustainability at the core of their operations,” says Janmejaya Sinha, BCG’s chairman of the Asia-Pacific region. “Whether because of a closer connection to the social, environmental and economic issues that drive sustainable business practices, or because it’s easier to implement changes in a fast-growing company, we expect sustainability capability and leadership to emerge from these regions and companies.” Certain investments are also more compelling for companies located in regions whose markets are growing. That is reflected in the results of our survey in which we find more embracers in these regional growth markets — areas such as Africa and the Middle East and Asia Pacific. At the same time, these embracers tend to be growing regional companies.

This is something noted by HSBC’s Robins. “One of the aspects of globalization is that you see excellence emerging globally — it’s no longer necessarily just coming from the United States or Japan or Europe,” he says. “We have seen some of the initiatives in our insurance division for green insurance coming out of Brazil, for example, and some of the clean-tech equipment business coming out of Hong Kong.”

FIGURE 5

Respondents’ self-reported sustainability spending in 2010 versus 2008, plotted by regional GDP growth.

Embracers Conceive of Sustainability Advantage Broadly

But profitability is not the only evidence of advantage seen by companies that are embracing sustainability as part of their business. While cautious adopters have not moved beyond considerations of cost cutting and risk management, embracers have identified a range of drivers that support their sustainability-related investments. These include increased margins or market share, greater potential for innovation in their business models and processes and access to new markets. And when it comes to competitive advantage, a significantly larger group of embracers (38%) picked it as one of the top three benefits sustainability had brought to the organization (only 21% of cautious adopters selected it).

FIGURE 6

Sustainability "heat map" comparing industry segments on the basis of sustainability being necessary to be competitive and on the existence of a business case for it.

The corporate leaders we interviewed told us the same thing. HSBC’s Robins points to growing markets in renewable energy, energy efficiency and battery technologies — segments that are closely linked to the bank’s core markets, giving the company the potential to develop new financing products. “Our clients are already moving heavily into these areas, some of them big industrial groups,” he says. “We have a reasonable share. And with investment coordination, we could claim a greater share.”

But while Robins is looking to claim a greater share of the market for sustainable products, companies such as HSBC and other embracers are already engaging in a significant amount of sustainability-related activities. And for HSBC, some of these activities represent disruptive rather than incremental change. For example, the bank has made a considerable investment in Better Place, the company that supplies services for electric cars. “That’s a private placement that we took, obviously in a sector which is highly disruptive both in transportation but also wider energy systems,” says Robins.

While the cautious adopters focus on efficiency, risk mitigation and regulatory compliance, the embracers say they are engaged in a range of activities, including sustainability analysis. Embracers say, for example, that they are analyzing the risks associated with not fully addressing sustainability issues. They are also assessing the expectations of investors and other stakeholders with respect to sustainability issues, including these issues in scenario planning and strategic analysis.

FIGURE 7

Embracers are three times more likely than cautious adopters to believe that sustainability decisions have been profitable.

However, embracers’ focus varies according to their company size, with smaller embracer companies focusing more intently on revenue streams and innovation than their larger counterparts. Meanwhile, larger embracer companies tend to pay more attention to the regulatory environment and the concerns of investors.

Some are also looking ahead to try to predict future regulatory changes. “One of the great uncertainties in my business every day is will there be a price on carbon,” says Duke Energy’s Bowman. “And if there is a price, what will it be, and when will it start?”

FIGURE 8

Comparing embracers and cautious adopters on the basis of what they think are the top three benefits of sustainability.

She is not alone. “We should mitigate the risks that regulation poses for the company and its business model,” says Graeme Sweeney, Shell executive vice president for future fuels and CO2. In fact, many corporate leaders told us that predicting the direction of national and global policy is an important part of their organization’s planning process. In this undertaking, companies are acting wisely, argues Ernie Moniz, director of the MIT Energy Initiative. “Certainly in the United States, cap-and-trade as a mechanism seems to have lost some of the bloom,” he says. “But it does not change the fact that we are moving toward explicit or implicit carbon constraints.”

Case Study: Unilever Lengthens Its Time Horizons

“Small actions, big difference” is how Unilever describes its recently launched “Sustainable Living Plan.” But unlike some companies — those that focus purely on the environmental impact of their operations — Unilever is taking its “small actions” and applying them to everything from environmental sustainability to the ways in which its global supply chain presents opportunities for job creation and income growth.

Santiago Gowland, the company’s vice president of brand and global corporate responsibility, describes the way the company arrived at this strategy as a journey with four stages: compliance, integration, transformation and systemic change. Compliance, for example, would be risk driven, focusing on reputation protection and license to operate. Meanwhile, integration for the consumer goods company would be the consideration of its social, economic and environmental impact and how they can be integrated into business processes to fuel innovation or cut costs.

Transformation, says Gowland, means using the sustainability aspects of its brands to take pressure off other elements of the business that are of more concern to investors or activists. He cites the Dove brand and its campaign to promote female self-esteem. “The social mission of Dove is part of sustainability in my opinion because it is dealing with social impacts of an industry, such as anorexia and bulimia,” he says.

FIGURE 9

Embracers are far more likely to consider intangibles and qualitative factors in their sustainability-related decisions.

Dove also contains palm oil, whose impacts include deforestation and destruction of the habitats of endangered species. However, the self-esteem values promoted by the brand take pressure off the palm oil issue, which is something Unilever is addressing not through branding but by shifting its supply chain away from palm oil and developing new sustainable sources of oil, such as the seeds of the Allanblackia tree, a crop the company is developing in parts of Africa. “That doesn’t really add a lot of value to the product brand propositions because it’s an ingredient,” he says. “The reason why Unilever is investing in that is because this is such a big issue, it’s operating at a risk level.”

That, he says, leads the company into the next stage: systemic change. “There is a huge amount of detail work in terms of how this links to the business development agenda,” he says. He adds that the systemic change stage means addressing environmental issues such as the sustainability of palm oil along with other major global challenges.

That, in turn, leads to consumer trust — a key component of the business for a consumer products group — and greater customer loyalty, not only in terms of the increased brand equity at a product level but also through the trust that is built at the company level. “When you realize that this is not just a compliance agenda but is something fundamental to enhancing the equity of our product brands, protecting our brands and leading the way forward, then it receives much more investment,” explains Gowland.

Unilever, he says, therefore views sustainability as a key business growth lever, treated at the same level as marketing, HR or supply chain management. In short, he says, it is a new way of doing business.

Whether or not their activities are governed by climate change regulations, embracers place consideration of environmental issues at the heart of their approach to sustainability (and they are much more likely to do so than cautious adopters). However, senior leaders told us that the way that they include environmental issues in their business strategy has changed.

For a start, they are moving away from relying on specialists to manage it. Walmart took this approach when it established 12 sustainable value networks across its business — covering everything from waste and energy reduction to sustainable products and supply chain. Each one was led not by an environmental expert but by a businessperson, so it became integrated into the business.

Shifting consumer demand is another reason for the change in approach to environmental issues. “We are a very customer-driven organization … and we started to see in our customer research that an issue like the environment was becoming much more important. So, that’s one of the things that led us down that path,” says Mike Pedersen, group head, wealth management at TD Bank.

P&G’s vice president of global sustainability Len Sauers traces the company’s environmental focus back to the 1960s, when it set up its first environmental lab to evaluate the safety of its products. “We largely saw sustainability as a corporate responsibility — as a large multinational company, it was simply the right thing to do to be environmentally responsible,” says Sauers. More recently, he continues, as the company began to see more external attention being placed on sustainability, the approach changed. “We began to think that sustainability could be more than a responsibility, it could be an opportunity to build the company’s business.”

Managing Change on the Adoption Curve

Where companies struggle when it comes to making sustainability an integral part of the business is often not so much with the technical side of things but with the human dimension of managing it. When TD Bank introduced its sustainability policy, Pedersen says many of the issues were new to its risk committee and board. Part of this was lack of familiarity with environmental issues, something that has changed in recent years. “I realized I was engaged in an exercise in lifting the collective IQ of the board around the environment, and I could see … all the lights going on and [people] realizing what the issues were.”

Since then, the company has made efforts to bring more of the staff on board to spread understanding of everything from energy markets to customer preferences. “We engaged all our internal constituents, all the employees, management, senior management and the executives,” says Pedersen. “Because to understand [what it means to be] carbon neutral, you have to understand carbon markets, you have to understand energy dynamics, you have to understand what’s in it for customers and so on.”

FIGURE 10

Comparing embracers and cautious adopters on the basis of what considerations are included when thinking about sustainability, where 1 = "not at all" and 5 = "to a great extent."

FOCUS: Intangibles and the Business Case

In comparing the way the embracers approach sustainability with that of the cautious adopters, we found one of the most significant differences to be in how they consider the intangible benefits of a sustainability strategy. These companies spend more time and effort quantifying the impact on their businesses of things such as brand reputation, employee productivity and the ability to attract and retain top talent. They also measure improved innovation capabilities in launching new products and services as well as in business models and processes.

Of course, such measurements are hard to make, as corporate leaders acknowledge. Duke Energy’s Roberta Bowman pointed to the value of resources such as water or to a culture of innovation, as well as costs like management time spent engaging with concerned stakeholders. “It’s hard to put a tangible number around these intangibles,” she says. While she admits that measuring them remains challenging, what has changed in recent years is that her colleagues are paying attention to them. “What gives me encouragement and what I feel is a sign of progress is that we’re having those conversations today, whereas a few years ago we may not have,” she says.

However, if some benefits cannot be measured in hard numbers, companies are beginning to see the impact they have on the business. For Johnson & Johnson, reputation management is translating into an enhanced ability to tap into top talent. “The younger generation coming into the work force is interested in going beyond just working for a company,” says Johnson & Johnson’s Al Iannuzzi.

The company recently made a presentation to MBA students at an event organized by Net Impact, a network of business students and young professionals. “The high-potential, new MBA students coming out are interested in working for a socially responsible company,” Iannuzzi says. “So if we weren’t doing this type of stuff, they would probably be looking elsewhere, at least a percentage.”

HSBC’s Nick Robins agrees. “Employee engagement is a critical KPI [key performance indicator] for the group,” he says. “That’s taken very, very seriously as a whole. And within that, sustainability is regarded as a key driver of employee engagement. Not just in an aspirational sense, but because it is measured in things like our annual global people survey.”

Meanwhile, when deciding on sustainability-related investments, embracers tend to apply the same financial standards — while factoring in intangibles and risks — as they would to other investments.

This approach, argues Shell’s Graeme Sweeney, is essential. He cites the company’s announcement of a proposed $12 billion joint venture with Cosan of Brazil, the world’s largest sugarcane ethanol producer, for the production of biofuels. Sweeney says that not only does development of biofuels offer one of the most realistic commercial ways to reduce CO2 emissions from road transport, but growing this business helps maintain shareholder value. “You make decisions based on a variety of factors,” he says. “But at the end of the day, you still have to make business sense.”

Responses from our survey suggest that, among embracers, similar strategies are being implemented. To drive sustainability internally, embracers assign managers to dedicated roles focused on sustainability and rely on line leaders and non-leadership employees more than other companies do. While top management teams determine strategy of their organizations as a whole, executives focused on sustainability range from chief sustainability officers or managers in dedicated sustainability units to managers in certain functions, such as supply chain management or units focused on particular offerings or customers.

In fact, for both embracers and cautious adopters alike, while senior leadership is seen as most strongly influencing an organization’s attention on sustainability, customers are the next most important group in this respect. That is reflected in corporate initiatives. At Johnson & Johnson, the consumer products division has hired a vice president of sustainability. For Unilever, shifting consumer demand is fueling innovation. “Consumers increasingly resonate with some of the social, economic and environmental messages of brands,” says Unilever’s Gowland. “Consumers want to buy brands that are good for them but also good for others.”

It is interesting to note that while embracers appear to be approaching sustainability in more sophisticated ways — making a better business case for it, and integrating sustainability strategies in everything from procurement and supply chain management to marketing and brand building — they say they face just as many difficulties overcoming sustainability challenges as do the cautious adopters. These include difficulty in predicting the value of customer responses to sustainability-related strategies, challenges in capturing comprehensive metrics about the sustainability-related impacts of their organization’s operations, and difficulty quantifying and valuing effects of sustainability-related strategies on the reputation of their brand, company or consumer offerings.

And some things are harder to measure than others. “Some of the strongest business cases we have seen are in the area of reducing energy consumption. Savings can easily be measured and credibly communicated,” says SAP’s chief sustainability officer Peter Graf. “That’s much easier than, for example, quantifying the positive impact of a more sustainable product on your sales figures or the brand value created by a social project in a developing nation.” Duke Energy’s Bowman agrees. “What I wrestle through, and what we work with as a management team on a day-to-day basis, is giving real value to some of the softer costs of business that may not necessarily be valued by the financial community,” she says.

World Is Tilting Toward Embracers

External Forces Are Pushing Business Toward Adoption

The external pressures prompting the adoption of sustainability-driven management — pressures the embracers are already noting and acting on — are increasing. First, public policy is having an effect, as governments continue to work toward carbon reduction and other targets. While much legislation remains at a national or local level, the global nature of business means local rules can be far-reaching. In Europe, for example, legislation requiring electronics producers to recycle their products at the end of their lives does not only affect European companies. Any business wanting to sell into this market must be compliant.

Second, institutional investors and pension funds are starting to look at their investments through a sustainability lens. The Carbon Disclosure Project, which pushes companies to disclose their climate change-related risks, now represents investors with some $64 trillion under management. And access to finance could also be a consideration in the future. Some banks are introducing sustainability-related loans, and even private equity firms are starting to consider the sustainability risks and opportunities in potential acquisitions. Meanwhile, as requests for capital come under increasing scrutiny, sustainability is becoming a factor in lending decisions.

FOCUS: Unlikely Partners Unite

Since conducting business in a sustainable manner means tackling tough environmental and social problems, leading companies have recognized that they cannot go it alone. As a result, the past decade has seen a wave of partnerships emerging between companies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Unilever’s Santiago Gowland points to the importance of this process when discussing how to develop sustainable supplies of palm oil. “It would be impossible to do anything about it without a coalition of government, industry and NGOs,” he says. “The scale of the issue deserves a global response that cuts across sectors. Otherwise, anything you do will be even more costly and less effective.”

The warming of relations between for-profit and nonprofit sectors has been a two-way process. Former anti-corporate campaign groups have become aware that progress can often be more easily made through engagement with the private sector than through activism. And cash-strapped nonprofits see that their mission can be accomplished more efficiently when tapping into the supply and distribution chains of big global companies.

At the same time, businesses understand that they are not necessarily well versed in water conservation or human rights, and so have turned to those with expertise in such areas. Shell’s Graeme Sweeney points this out when talking about the land use changes necessary for biofuel production. “You need a broad collaboration on biofuels around land use change, which requires proper interactions with NGOs such as IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature], with whom we have established partnerships, and with a strong society at large,” he says.

But while a significant warming of relations has taken place between these groups and the corporate sector, Gowland believes this process needs to go further. “One of my obsessions right now is how governments, NGOs and business-persons can work together better — how can we overcome ideological differences?” He argues that all these players need to put their capabilities on the table “to solve critical issues that, in my view, are taking too long to be solved.”

Third, employees are driving the agenda. As job candidates, they are holding potential employers under increasing scrutiny regarding their track records on sustainability. And while this does not necessarily trump pay and benefits, sustainability credentials are having an increasing influence on the decisions of job seekers.

FIGURE 11

Industry comparison on the role that sustainability plays in being competitive.

Customers, as our survey has shown, are also proving a powerful force in shaping the new business landscape. P&G’s director of global sustainability Peter White first noticed this in 2006. “That was very much a point of change,” he says. “We had, for the first time, customers asking us for more sustainable products … that was the point at which we set a new sustainability strategy.” Walmart Canada has seen this consumer attention intensify among the business community, the general population, and its customer base.

Some additional strengthening megatrends such as the trends toward green and toward accountability — also underpin moves to incorporate sustainability into business operations. Increasing demand for green products such as energy efficient appliances, green mortgages and hybrid vehicles is shaping companies’ development of new products and services, as is demand for health and wellness and organic products. And the new era of accountability means measurement and reporting of companies’ environmental and social impact will take on greater prominence.

Cautious Adopters Are Aiming to Catch Up

If the embracers already know much of this, so, too, do rising numbers of cautious adopters. Two survey findings suggest that the cautious adopters have begun to recognize that where the embracers are is where the world is headed, and that the embracers’ behaviors offer a provisional blueprint for how management practice and corporate strategy will evolve.

One piece of evidence emerges in the answers to the question, “Is pursuing sustainability-related strategies necessary to be competitive?” Respondents in some industries answer “yes,” in many other industries, “no.” The variances are wide, ranging from 80% “yes” from respondents in the auto industry to just 29% in media and entertainment. However, when you add those executives who responded, “No, but will be in the future,” those gaps close across the board, particularly in the currently lagging industries, with 88% of respondents saying that sustainability-driven strategies will be necessary to be competitive — if not right now, then soon.

FIGURE 12

Comparing the change in sustainability commitment from 2010 to 2011 between embracers and cautious adopters

The second finding returns us to the question of planned increases in sustainability-related management attention and investment. The embracers are well in the lead here, with 87% saying they increased their spending in 2010 and 88% predicting that they will increase their spending in 2011.

However, significantly, the cautious adopters appear to have grasped how the sustainability agenda is changing and so are catching up with the embracers.

From 2010 to 2011, the number of cautious adopters planning to increase their sustainability spending jumps 24%, while the embracer numbers, though high, remain flat. In 2010, 51% of cautious adopters said they had stepped up their sustainability investments compared with 63% who said they would show increases in 2011. The commitment of the cautious adopters is increasing at a far higher rate than that of the embracers.

What those trends indicate is that most companies — whether currently embracers or not — are looking toward a world where sustainability is becoming a mainstream, if not required, part of the business strategy. And those not already putting sustainability at the heart of their business are planning on doing so in the near term. Sears Canada’s manager of sustainable supply chains Katie Harper agrees with this analysis. “It seems that even people who aren’t really doing much of anything right now are getting the message that this is something they’re going to have to be thinking about,” she says. “This is just part of the way things are going to happen now.”

Follow the Leaders

How to Do What the Embracers Do

It is not surprising that most companies (all but the 3.5% of respondents who qualified as true sustainability skeptics) believe sustainability will be necessary to be competitive in the future and so see the need to accelerate their adoption of sustainability-driven management. But what does that mean, exactly? How can it be done? What are the high-leverage tactics and strategies that will transform the way an organization competes on sustainability?

Our study suggests that the behaviors and experiences of the embracers may provide a starting point. If the embracers are in the vanguard and present a picture of what management increasingly will look like as businesses turn to sustainability for competitive advantage, they also portray the early-stage steps that any company could take to advance along that path. What do the high-performing embracers do that other organizations might benefit from adopting?

In our study, along with identifying who the embracers are, we discovered seven practices that typical embracers share. What do embracers do? They:

Case Study: Clorox Applies Mainstream Principles to the Business Case

Beth Springer is not given to overstatements when asked how far she thinks her company has gone in integrating sustainability into its business. “We’ve been on a journey for several years,” she says. “And we’ve reached a point where we have an idea of how we want to proceed and of some of the benefits as well as the challenges.”

It is a realism that helps Clorox make the business case for sustainable development. The company has worked to set goals and metrics for its different business units and functions in areas such as greenhouse gas reduction, solid waste reduction and water reduction, and has introduced “eco-assessments” to assess the risks and opportunities in each of its business units. “It’s come to a level where it’s concrete enough and driven down into the organization so that it’s becoming part of the fabric of the business,” says Clorox’s executive vice president of international and personal care.

Part of the pressure to do so has been internal, from employees who want to work for a company that takes social and environmental responsibilities seriously. “And I think, as is always the case, if you didn’t have a few senior people who took it on as a mission, it wouldn’t happen,” says Springer. However, external forces are at work, not only in the form of consumers and advocacy groups, but also retail customers such as Walmart, which is pushing its sustainability agenda down into global supply chains.

But to overcome any resistance, Springer stresses the need to make the business case in the same way a company would for any strategy. “We treat it that way — it’s not something special that deserves a pass on having a strategic and financial rationale,” she says. “At the same time, it’s not a project we’re undertaking because it’s going to dramatically improve EPS [earning share] in the short term.”

Even so, Clorox has seen tangible and intangible benefits emerge from making sustainability a priority, and consumer demand has helped it in the repositioning of product lines such as Brita, the launch of Green Works cleaning products and the acquisition and growth of Burt’s Bees all-natural personal care. “Most of our biggest growth opportunities are in capitalizing on consumer megatrends,” explains Springer. Part of this, she says, is the desire to improve health and wellness. “But it’s also about people’s desire for more natural and more sustainable products.”

While the U.S. economic slowdown has dampened growth in Green Work’s and Burt’s, both are still good businesses. “If you can meet category performance requirements, command a bit of a premium and you can commit to continuous cost reduction in those products, then you can make money on natural products,” says Springer.

Ultimately, one of the biggest benefits has been the reaction of employees to the company’s sustainability focus, something Springer saw after the company declared its eco strategy and introduced office sustainability initiatives such as double-sided printing, recycling and using virtual meetings to reduce travel. “They’re totally into it,” she says. “It makes them feel good and like they make a personal difference. They’re proud of the company. And that to me is proof positive that this helps you attract, retain and engage employees.”

1. Move early — even if information is incomplete. First, they tend to be bold, see the importance of being an early mover and be prepared to accept that they need to act before they necessarily have all the answers. Business leaders we interviewed tend to agree. “Much of what you do in business can’t be reduced simply to a formula or to a financial return calculation,” says Brian Walker, CEO of Herman Miller. Many decisions, he says, “require a bit of instinct, a gut feeling for where you’re ultimately trying to go. It can’t be reduced to simply a piece of paper.” Duke Energy’s Roberta Bowman sees sustainability-driven management as a journey, in which different businesses are at different stages. “It is an evolutionary process, and companies go through stages of growth in adapting sustainability to their business,” she says. “Even within a complex company, we are starting at different places, we are evolving in different ways with our approach to sustainability.”

Embracers are not paralyzed by ambiguity, and instead see action as a way to generate data, uncover new options and develop evidence iteratively that makes decision making increasingly effective. Movement diminishes uncertainty.

2. Balance broad, long-term vision with projects offering concrete, near-term “wins.” Leading companies are striking a balance between an overarching vision and being specific about the areas where they can gain competitive advantage. An ambitious vision might generate brand premiums, transform organizational culture and help attract capital, talent or public collaborators. But smart embracers balance those aims with narrowly defined projects in, say, supply chain management, which allow them to produce early, positive bottom-line results. They exhibit relentless practicality.

Dan Esty, professor of environmental law and policy at Yale University, sees this two-mindedness dividing the leading companies from the laggards. “The emphasis on execution is going to separate a few leaders from the pack who may have seen change coming but have not positioned themselves to act on the opportunity.”

3. Drive sustainability top-down and bottom-up. Leading companies recognize that sustainability must not only be driven from top down — with leaders prepared to talk openly about the challenges and opportunities it brings their organization — but must also involve employees, creating incentives (both financial and managerial) to contribute. SAP’s Graf believes that employees have a key role to play. In fact, he says this was something that, initially, his company underestimated. “The first surprise was that some of our employees were much more aware of sustainability challenges and potential solutions than our management team,” he says. “Our employees have long understood the role SAP can play. We saw a lot of grassroots activities happening around the globe, and were amazed by the degree of passion that went with it.”

Embracers have learned that working to enlist employees in sustainability at all levels has many benefits. In addition to gaining ideas and insights from multiple sources, the genuine involvement of staff in that process drives up levels of employee engagement and productivity, and nurtures a culture that is attractive to talented recruits.

4. Aggressively de-silo sustainability — integrating it throughout company operations. Embracer companies do not treat sustainability as a separate function but have established a culture in which sustainability is applied to all existing business processes. “We are now looking at much more precise ways to build sustainability into our core business processes, whether that’s our integrated resource plan or our view of merger and acquisition candidates,” Duke Energy’s Bowman says. She argues that it may not even need to be called “sustainability” to be wired into the business. “It’s the approach, it’s the process, it’s the mindset.”

In some cases, integration means embracing opportunities; in others, it means addressing risk. For HSBC, for example, bringing sustainability into lending practices is one way of integrating it into the business. “HSBC has a series of very clear and unambiguous policies around the standards we have for financial relationships with clients in forestry, water, chemicals, energy, metals and mining,” says Robins. “That goes straight through the credit risk function, and I think it’s a well-understood and formal process. And so that provides a very clear way of integrating material risk into the business decision making.”

5. Measure everything (and if ways of measuring something don’t exist, start inventing them). Embracers establish baselines and develop methods of assessment so that starting positions can be identified and progress measured. Some of these assessments are of tangible or physical activities, such as waste and energy efficiency or water conservation. However, forward-thinking companies are also trying to establish ways of quantifying the impact of sustainability on brand, innovation and productivity.

Assessments that make the link between a company’s sustainability credentials and its employee engagement are of particular interest to companies as they recruit skilled executives who want to work for a company they believe is doing the right thing. This issue is extremely important to most employee populations, particularly millennials. And although many people see this as a big, complex, intellectualized issue, the employee population in sustainability is going to become bigger, and employees are simply going to demand it from organizations.

Of course, the way companies develop their approach to the measurement of intangibles is likely to vary according to their sector and activities. Mechanisms already exist that companies can adapt, such as employee satisfaction and exit interviews or the number of times analysts ask to see sustainability-related information. Initially, these kinds of metrics make intangibles more tangible — and, critically, they may help develop data that can tie less tangible sustainability-related rewards to the organization’s financials.

6. Value intangible benefits seriously. Embracers are clearly distinguished from cautious adopters in their readiness to value intangibles as meaningful competitive benefits of a sustainability strategy. Smart companies are realizing that conservation of natural resources they need is a fundamental part of risk management, as the work being done by companies such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo on water conservation clearly demonstrates. And starting a sustainability journey by focusing on waste and energy inefficiencies makes sense for any business.

However, embracers accept that it takes time to develop their ability to measure — or even to understand fully — intangible advantages, and they need to make their investment decisions on the basis of a combination of tangible benefits, intangibles and risk scenarios. That certainly applies to oil companies, according to MIT’s Moniz. “They are looking at step-outs — things that are not part of the core business today but are preparing them for a potentially very changed portfolio in 10 or 20 years,” he says. “But they’re also doing work that goes to their core business.”

7. Try to be authentic and transparent — internally and externally. Finally, companies leading the charge on sustainability are fundamentally realistic. They do not overstate motives or set unrealistic expectations, and they communicate their challenges as well as their successes. That was something embraced early on by companies such as Nike and Gap, which in the mid-2000s started producing labor supply chain reports that included details of the supplier factories in which they had encountered noncompliance with labor, environmental and health and safety standards. Unilever has also demonstrated that it is looking toward long-term horizons, even if that means less impressive results on its short-term margins.

Unilever is taking an open approach to communications, as was seen recently in its public pronouncements about its Sustainable Living Plan, in which company CEO Paul Polman emphasized the need to move away from a focus on short-term profit margins. Polman also stressed the fact that Unilever had not yet come up with answers to many environmental and social sustainability challenges in its operations but would work in partnership with other sectors to do so.

The “warts and all” approach to reporting and communication has yet to be adopted by many companies — embracers included. Those that do communicate openly find that this shores them up against accusations of “greenwashing,” both internally from employees and externally from stakeholders, customers and activists.

Conclusion

Like most business trends, sustainability has not emerged in a vacuum. First, it is a reaction to the growing risks and uncertainties companies face, such as scarcity of natural resources, the rising price of carbon and looming environmental legislation, as well as external pressures from consumers, supply chain customers, advocacy groups and investors. Consequently, what the boldest companies are finding is that once they view their business through a sustainability lens, opportunities are emerging that might not have otherwise been identified.

That relates partly to the readiness of some companies to learn while doing, accepting that they do not yet have all the answers or measurement metrics in place, but pushing ahead regardless. In the course of this research, many business leaders described this process as a journey with surprises and discoveries emerging along the way.

Of course, many companies — cautious adopters included — understand that resource efficiency benefits the bottom line. But while measuring resource use and waste efficiency is a good way for companies to start the process of measuring sustainability and basing investment decisions on that information, the more intangible rewards of embracing sustainability, such as employee engagement or the ability to innovate, are equally if not more important to business success.

Companies still have some way to go in measuring these intangibles, and they are wrestling with the financial side of how to use them to make the business case for investing in sustainability. Yet in our research, business leaders say that these are important and beneficial side effects of adopting sustainability, and they are starting to look for ways to assess them.

Moreover, in embracing sustainability, leading companies are shaping the agenda. Cornell’s Hart cites the example of SC Johnson, which removed chlorofluorocarbons before their removal became enshrined in legislation. He points out that this did the company’s financial performance no harm; in fact, the decision ended up driving innovations that later paid off handsomely. “They just rip it,” he says. “They’re a highly, highly profitable company.”

But whether shaping industry landscapes or making new discoveries and innovations in their own operations, companies that are moving most aggressively on the sustainability agenda are doing more than reducing their environmental impact.

These companies are measuring sustainability commitments in the way they would any other investment. They are setting realistic expectations for the return on those investments. And yet by heading down one path — by taking that leap of faith — they are finding that unexpected benefits emerge. Employees are more engaged in meeting environmental goals than had been anticipated. Brand value is enhanced, often in unexpected ways. Partnerships generate unanticipated sources of innovation. In short, sustainability is revealing new paths that will enhance companies’ long-term ability to compete.

Companies hoping to gain advantage in a more sustainability-driven world should therefore be looking at the practices and approaches being adopted by the embracers identified in this survey. Our results show that many cautious adopters are starting to follow these leaders. Embracers provide a crystal ball through which to view the future business landscape — one in which risks and opportunities are going to be increasingly shaped by what it means to be a truly sustainable business.

About the Research

To discover how, and how fast, companies are adopting sustainability management practices, MIT Sloan Management Review in collaboration with The Boston Consulting Group conducted a survey of more than 3,000 business executives and managers from organizations located around the world. The survey captured insights from individuals in organizations in every major industry, ranging from those with fewer than 500 employees to those with more than 500,000 employees. The sample was drawn from a number of different sources, including MIT alumni, MIT Sloan Management Review readers and subscribers, BCG clients, alumni, and other interested parties.

Download just the Survey Questions & Responses »

In addition to these survey results, we also interviewed academic experts, subject matter experts, and senior executives from a number of industries and disciplines to understand the practical issues facing organizations today. Their insights contributed to a richer understanding of the data, and the development of recommendations that respond to strategic and tactical questions senior executives address as they work to build a business case for sustainability and embed it into their operations.

Early findings from this research were published in the Winter 2011 issue of MIT Sloan Management Review.

Early findings from this research were published in the Winter 2011 issue of MIT Sloan Management Review.

The complete survey, with questions and responses, is available as 6-page pdf.