Designing the Right Product Offerings

Companies create product versions from multiple components. The big challenge is how to take the available components and combine them into the product versions and product lines that will maximize profits.

Topics

Businesses are constantly making decisions about which products and services will attract customers. In an era driven by the mantra of “give customers what they want,” some businesses feel compelled to offer many different versions of their products. This trend is relatively new. For years, blue jeans came in only one shade of blue and in only one style, but now they are available in a dizzying array of styles and colors. Yet some companies continue to stick to a single version of their products, making alterations only when technology impacts what they can provide or when competition shifts. Music publishers, for example, after decades of providing mainly bundles of songs on compact discs or records, have, in recent years, made individual songs available as well — thanks to technological changes that have made distribution over the Internet less costly to them and more efficient for consumers.

How can companies design products and product lines to maximize their profits? Out of all the potential configurations available, how should companies decide which ones to offer? We have developed a framework for balancing the costs of developing and offering a rich line of products and services against customer demand for additional choice. (See “About the Research.”) Our methodology allows managers to make informed decisions about product-offering architecture: which features to include in the product, which variations to include in a product line, and how the goods should evolve with technology and competition. In particular, our approach highlights how costs influence the design of the most profitable offering.1 Thus, it departs from the standard product-success metrics, such as revenue and market share, which are the primary focus of most of the work on product bundling.2

The ABCs of Product Architecture

By conceptualizing products as being built from components, product architecture helps companies narrow the field of possible features and combine them into the product version or versions that maximize profits. Sometimes, this means developing both a basic product and other versions that come bundled with state-of-the-art features (for example, mobile phones that can play videos from the Internet).

Companies make product-offering architecture decisions in response to market and technological forces as well as shifts in business models. In the automobile industry, for example, carmakers must decide which features to include in their base products, which ones to make available as options and what to leave to aftermarket suppliers. Prior to World War II, automakers did not offer air conditioning on any of their models, but they gradually made it available on selected models in response to growing consumer demand.3 Now, most car models in the United States come with air conditioning as standard equipment, even though some consumers, such as people living in colder climates, use it infrequently and would rather not have it at all. Until recently, navigation systems were strictly an aftermarket product.

To understand why companies commit themselves to product configurations that may not meet the needs of customers, one must first understand what drives consumer choice at any point in time. To illustrate what product architects face, let us consider a simple case where companies can create product versions from two distinct components, which we represent with a square and a triangle. Each shape represents a distinct product that could be sold as a stand-alone version or combined to make something more appealing to the end customer. The square could represent the base product (for example, a credit card), while the triangle could be a possible upgrade option (such as concierge services for premium cardholders). Alternatively, the square and triangle might represent two products that could be sold separately — for example, a hotel room and access to high-speed Internet — but could also be combined into a package (hotel guests getting “free” high-speed Internet connections in their rooms).

Using the two components, it is possible, when the components could in principle be sold separately, to offer three distinct products: a triangle product, a square product or a combination that consists of, say, the square with a triangle on top.4 Indeed, adding the triangle to the square creates another version of the product. It may be that by combining components, the producer creates added value for consumers who want both features and derive convenience from being able to get them together. The bundle is therefore more valuable than the sum of its components.

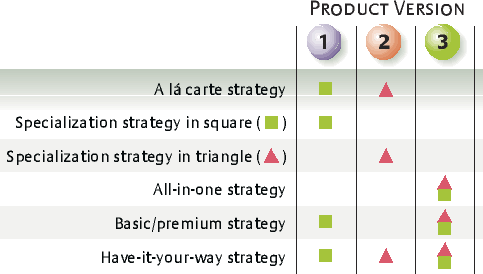

Companies have the ability to fashion five distinct types of products from the three different products (square, triangle and square plus triangle) that can be built from the two components (the square and the triangle). (See “Spectrum of Product Offerings Using Two Features.”)

A la carte offering

With a la carte, companies can treat different product features individually, allowing consumers to create the product version that suits their needs best. Sony Corp., for example, produces both televisions and DVDs. This allows consumers to bundle the two products on their own if they choose.

Specialization offering

Companies use specialization when they realize economies from providing one basic product feature that customers want or that customers can combine with other features. For example, MAXjet Airways Inc. offers only business-class service and Southwest Airlines Co. offers only coach.

All-in-one offering

The all-in-one product combines all the different product features, removing the customer’s ability to order items separately. For example, newspaper publishers don’t allow you to buy the daily paper without the sports or classified sections, even if you never read them.

Basic/premium offering

The basic/premium product strategy permits companies to offer both a basic product and a premium version that includes some additional features; however, consumers can’t “unbundle” the basic product to get the features they want. For example, cable customers generally can’t get ESPN without also receiving a basic cable package that includes standard channels.

“Have-it-your-way” offering

These offerings are not mutually exclusive, and some companies offer an array of possibilities. Microsoft Corp., for example, sells the complete Office software suite, but it also lets customers buy the individual software programs separately and several versions of the Office suite with different features. Cable companies offer many different combinations of channels — from basic to super-premium — in addition to providing bundles that include high-speed Internet and voice over IP phone services.

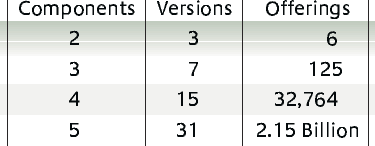

Depending on the nature of the product, the number of alternative products increases exponentially with the number of features. For example, three distinct product features can be combined into 125 distinct products by varying the composition of the bundles offered to customers.5 Practically speaking, many product features can’t be sold separately (for example, pockets for jeans) which reduces the number of combinations in practice. Nevertheless, in many real-world settings the number of offerings increases with the number of features available. (See “The Mathematics of Product Offerings.”)

The mathematics of the potential combinations has two important implications. First, companies won’t find it profitable to provide all the products that they could make from the components available to them. And second, as a consequence, consumers generally can’t get all of the product versions that they might choose in a perfect world. Our method for designing product offerings gives managers a tool for isolating the most profitable product lines from all possible combinations while evaluating the inherent trade-offs between the costs and benefits to both consumers and companies alike. (See “Rules of Thumb for Product Architecture.ȁ)

The Role of Cost in Configuring the Most Profitable Product Offering

Maximizing long-term profits requires assessing the cost of making offerings available to consumers and the anticipated level of consumer demand. First, let us consider costs.

From the perspective of the company, the decision to offer a product and how it is designed generally affects both the fixed costs (the costs the business incurs regardless of how many units it sells) and the marginal costs (the costs the company incurs for each additional unit sold).

Fixed Costs

When a company offers multiple products, the fixed costs typically relate to the packaging and retail shelf space required for each. An advantage of an all-in-one offering is that the fixed costs of a single product will almost certainly be less than providing two separate products a la carte. A newspaper, for example, economizes on printing and distribution costs by offering a single print edition.

Marginal Costs

The effect of product bundling on marginal costs is more complex. Adding product features can result in interdependencies among product and service components that may lead to higher design costs and sometimes even costly service calls or product recalls. Such costs tend to be greater for complex durable goods and professional services than for information-based ones. For example, adding a higher-resolution camera to a mobile telephone or a business-strategy consulting practice to an accounting firm is more costly than adding a new home and garden section to a newspaper.

In some cases, however, integrating separate components can reduce marginal costs. Consider the example of over-the-counter medications. Rather than making one tablet to treat headaches and another to treat colds, it is cheaper to produce a combined tablet that relieves the symptoms of both because the costs of the chemical ingredients are only a small fraction of the total cost. The marginal cost of the combined tablet is less than the sum of the marginal costs for the two tablets. Companies should carefully assess the effect of product combinations on their marginal costs. They may be surprised at the additional costs of producing things together, or they may uncover ways to economize on packaging and other costs.

Information-based products — in particular, software and media — are different from most other goods in that it is possible to add another component to the product with little or no effect on marginal cost. Adding another song to a CD costs virtually nothing so long as there is space on the disc. Likewise, when Apple Inc. adds another software feature to its iPodiTunes platform, the cost is minimal.6

Technological change and organizational improvements enable manufacturers to manage the fixed and variable costs of their products more effectively. Lean manufacturing techniques, including just-in-time inventory methods, allow companies to reduce their costs while customizing their products. Dell Inc.’s business model, for example, combines both low cost and choice. However, choice generally comes at a cost, and businesses ultimately face a trade-off between presenting consumers more choice and offering consumers lower prices as a result of reduced costs.

Product architects need to expand their definition of fixed and marginal costs beyond those that they typically track and account for. They must consider costs across the entire supply chain because these will ultimately affect the costs they need to recover. These include so-called complexity costs resulting from the impact of multiple product versions on management and production time, which ultimately drive up the cost of the product. Although some of these may be hard to quantify, they are often too significant to ignore.7

Tapping Consumer Demand: Aligning Price and Preference

Consumers will usually say that they want to get the version of the product that is “right for them.” However, their appetites for different features vary, and they also have differing abilities to pay for premium versions. This heterogeneous demand tends to support a have-it-your-way or a la carte strategy as a way to give consumers as much choice as possible.

In many situations, however, consumers reject choice in part because of the higher costs.8 They find they can realize savings in both time and effort when product features are combined (as in the headache and cold pill or smart phones that provide e-mail capabilities). Downloadable music enables people to buy individual songs, but some consumers still prefer buying the bundles of songs the artists and music publishers put together; it saves time, reduces risk and improves efficiency overall. (See “The Music Industry: A Case Study.”)

In choosing among the five possible product alternatives, companies must weigh the costs of alternative product lines against the expected demand and the costs for exploiting this demand. There are two key consumer-demand strategies companies can use to assess the willingness of consumers to pay for different versions of products against the profit-maximizing potential of them: aggregation and segmentation.

Aggregation.

Aggregation is especially important for information-based products because it is cheap to add features to generate extra demand.9 Consider a family’s decision to subscribe toThe New York Times. The woman may be interested in national news and the arts sections. The man may be drawn to the business section and articles about science. Their 16-year-old son may like having access to the newspaper’s online database for homework research. None of the family members would be willing to pay $9.30 a week individually.10 But the combination of features makes it an attractive household investment.

Aggregation is related to the law of large numbers, which informs how the universe of potential customers values different aspects of a product. For example, whenThe New York Times combines numerous features in its paper, chances are that some set of those features will appeal to consumers who will then pay the full subscription price. There are, of course, significant fixed costs in creating the basic product, but the incremental cost of adding features or distributing those additional features to consumers is low.

Companies generally use aggregation strategies by making an all-in-one product. As a result, consumers often end up getting features they don’t care about. Some may find this irritating, but more often the benefits of ignoring the features they don’t want far outweighs the costs of either doing without the item or paying more to eliminate the annoying feature. Consumers generally benefit from aggregation because it keeps their costs low and allows producers to realize scale economies that are passed on in the form of lower prices. For example, ifThe New York Times had to distribute each section separately, the company would no longer have scale economies; it would probably have to raise prices (not that they wouldn’t raise prices anyway) or eliminate sections.11

Segmentation.

Companies often design products based on how much demand they envision from a certain customer segment. Services enterprises often use this approach as well. It creates an opportunity for companies to charge a premium to customer groups that want a particular package, and then to price the no-frills version of the product more aggressively. For this approach to be effective, there must be a predictable correlation between features and demand; for example, you need to know that price-sensitive airline travelers will not pay extra for in-flight meals. That is a major reason why companies develop “basic/premium” products — providing a basic package to price-sensitive customers and a higher-price, feature-rich package to those less sensitive to price. A have-it-your-way product can also be used to segment demand by charging different prices for different alternatives.

This last point raises an important aspect of product design. Businesses can deliver great value to particular segments of consumers by adding features to a product. Often it does not cost much to do so, but it can permit higher markups — and therefore higher profits. Many studies show that U.S. automakers realize much higher margins on their luxury models than on their base models.12

Identifying the Best Product Line

What ultimately matters to product architects is who will buy, what they will buy and how much they will pay. That is more complicated than it seems on the surface, especially when the goal is to maximize profits rather than revenues. Our approach to product-offering architecture can provide much needed insight.

Step 1: Model demand and pricing for alternative offerings.

For each possible product line, the company must determine what prices to charge consumers by examining the cost-benefit of different aggregation and segmentation strategies with an eye toward achieving optimal demand and maximum profit. Once managers decide which strategy (aggregation or segmentation) will yield optimal demand and determine how much to charge, they can forecast revenues from each product in the product line and from the product line as a whole. For example, they can compare a basic/premium product as part of a segmentation strategy to an all-in-one offering as part of an aggregation strategy.

In making these decisions, managers have to keep two things in mind. First, offering a new version of a product can cannibalize sales from the original; for example, some customers who previously bought the bundle may opt to buy only one feature. Second, giving consumers an additional choice — for example, a no-frills automobile — may persuade consumers who didn’t want the all-in-one alternative to purchase a less complete version. These market-expansion effects (where more consumers are attracted by the product-line extensions) also account for differences between the revenues that can be realized with different products. The alternative products, although possible to deliver, could also have negative implications for the overall fixed and variable costs.

Step 2: Weigh costs against revenues.

Naturally, the best product is the one that generates the highest profit after taking cost, demand and pricing strategies into account. Designing products, however, becomes vastly more difficult as the number of possible alternatives increases. Product architecture helps companies focus only on the subset of offerings likely to be most profitable, starting with whether there is enough demand to warrant the fixed costs of making a product available at all.

It stands to reason that companies should compare the fixed cost of offering a product against the demand for it. It does not make business sense to produce many products when there isn’t enough demand for them, although sometimes lack of demand does not become apparent until after the product is introduced.

Other times, the fact that there is enough demand to warrant a particular product configuration only becomes clear after the company weighs the cost of offering the product against the incremental demand for it. For example, many carmakers have concluded that it is expensive to offer too many car models with different options and have scaled back the number of choices in order to reduce costs. It is easy to see from these considerations why it is profitable for businesses to offer only a fraction of the products (defined by the combination of components) they could make. Even relatively modest fixed costs would encourage producers to restrict the number of products to those for which there is significant demand.

Technological change can alter these trade-offs. For example, Internet distribution has made it cheaper for software companies to distribute multiple versions of mass-market software without having to incur costs in packaging each version separately and taking up scarce shelf space with multiple versions. The ability to miniaturize components also makes feature-rich versions of products more appealing to consumers. Since a camera on a mobile phone takes up little space, consumers who don’t care about this feature can easily ignore it. According to the “long tail theory,” Internet-related innovations have made it cheaper to serve narrow niches of consumers with specialized products.13 This may be true in part, although it overlooks the fact that aggregation strategies have also become cheaper.

Designing products in response to competitive threats also affects these trade-offs. Managers might infer that when competitors offer more product variety they are doing it because it is profitable. And it may be. However, the fixed costs of offering more products may limit the number of businesses that can profitably serve customers. In fact, matching the competition may be a money-losing proposition. The most profitable strategy may be to specialize in a small number of offerings to larger consumer groups, letting boutiques focus on the niches.

OUR APPROACH TO PRODUCT-OFFERING architecture provides a framework for helping businesses create products and product lines that maximize their long-term profits. It is based on the premise that there are both costs and benefits associated with choice. There are costs for consumers because they need to acquire information, make decisions, take risks and incur other transactions costs. There are costs for companies because they need to maintain additional production capabilities, design more packaging and pay for additional shelf space. By definition, offering many different features requires more resources, resulting in higher costs and opportunities for higher prices and profit.

But choice also provides important benefits. Consumers value some choice, although the degree varies by product and circumstance. Businesses value it, too, because it allows them to segment their markets and charge higher prices. The most profitable product lines are those that balance the benefits and costs for both consumers and businesses.

References

1. For a summary, see D.S. Evans and M. Salinger, “The Role of Cost in Determining When Firms Offer Bundles,” Journal of Industrial Economics, in press. See also D.S. Evans and M. Salinger, “Why Do Firms Bundle and Tie? Evidence from Competitive Markets and Implications for Tying Law,” Yale Journal on Regulation 22, no. 1 (Winter 2005): 38–89.

2. W.J. Adams & J.L. Yellen, “Commodity Bundling and the Burden of Monopoly,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 90, no. 3 (August 1976): 475–498; R. Schmalensee, “Gaussian Demand and Commodity Bundling,” Journal of Business 57, no. 1 (January 1984): S211–30; and R.P. McAfee, J. McMillan, and M.D. Whinston, “Multiproduct Monopoly, Commodity Bundling, and Correlation of Values,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 104, no. 2 (May 1989): 371–383.

3. See http://web.archive.org/web/19990423055451/vintagecars.tqn.com/library/weekly/aa050898.htm.

4. Let n be the number of features and v be the number of product versions, then v=2n-1. Thus, with three features it is possible to construct seven different product versions, and with four features it is possible to construct 15.

5. Let o be the number of product offerings. Then o=2v-1 = 2(2n-1)-1.

6. Y. Bakos and E. Brynjolfsson, “Bundling Information Goods: Pricing, Profits, and Efficiency,” Management Science 45, no. 12 (December 1999): 1613–1630.

7. Evans, “Why Do Firms Bundle and Tie?” supra, note 1, for a summary of the evidence that automobile companies incur significant costs as a result of offering numerous different products.

8. B. Schwartz, “The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less” (New York: HarperCollins, 2004).

9. Bakos, “Bundling Information Goods,” supra, note 6.

10. See http://homedelivery.nytimes.com

11. Companies can also use an all-in-one offering to implement a block-booking strategy — named after a 1963 paper by that name by Nobel prize-winning economist George Stigler — that enables companies to obtain a greater portion of consumers’ willingness to pay for products. Stigler demonstrated this strategy by examining the economics of movie distribution. Suppose that theater 1 is willing to pay $8,000 and theater 2 is willing to pay $7,000 for movie A; and that theater 1 is willing to pay $2,500 and theater 2 is willing to pay $3,000 for movie B. If the movie distributor charged a single price to the two distributors, it would charge $7,000 and $2,500 to attract both theaters; the distributor would collect $9,500 from each for a total of $19,000. But consider how much the theaters would pay for both movies: Theater 1 would pay $10,500 and theater 2 would pay $10,000. Thus, if the distributor charged each $10,000 for the bundle — block-booked the movies — it would collect $20,000 and therefore make more money.

12. S. Berry, J. Levinsohn and A. Pakes, “Automobile Prices in Market Equilibrium,” Econometrica 63, no. 4 (July 1995): 841–890.

13. An extensive discussion of the long tail theory can be found in C. Anderson, “The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More” (New York: Hyperion, 2006). The long tail theory posits that the Internet allows a large number of people access to a wide variety of items, which creates new, albeit in some cases small, profitable markets for goods and services.