Introduction

In 2008, the year David Gledhill went to work for DBS Bank, few would have predicted that within a decade the Singapore-based bank would be racking up an impressive slate of honors. Nonetheless, DBS was the first recipient of Euromoney’s Best Digital Bank Award in 2016; it received that distinction again in 2018 and, that same year, was also named Global Finance’s Best Bank in the World.

Just a decade ago, however, DBS, beset by long lines at branches and ATMs, high turnover among relationship managers, and a plodding credit card application process, had the worst customer satisfaction scores of all the banks in Singapore. Chief data and transformation officer Paul Cobban, who came aboard in 2009, recalls that “it was almost embarrassing to tell people at dinner parties” that he worked for the bank “because DBS had such a bad reputation.”

Executives did not simply change their performance management systems to achieve these goals. They redefined the meaning and measurement of performance.

Soon after Cobban joined, a newly arranged management team, with the support of tech-savvy CEO Piyush Gupta, turned things around by thinking of DBS as more of a tech startup than a bank. Gledhill, DBS’s CIO, says, “Our future competition wasn’t going to come from just banks, but from a lot of cool technology companies that were going into finance.” DBS, in Gledhill’s words, committed to becoming “digital to the core,” and he and his team initiated a thoroughgoing culture change to support digital innovation.

Executives did not simply change their performance management systems to achieve these goals. They redefined the meaning and measurement of performance.

Company Background

DBS Bank was established by Singapore’s government in 1968 as the Development Bank of Singapore Limited. (It became known as DBS in 2003.) Still headquartered in the island nation, the multinational financial services group, with a workforce of over 26,000, has expanded throughout China, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, and currently has 280 branches in 18 markets. With its focus in recent years on reimagining banking as a seamless and streamlined digital experience (it has made banking mobile-only, paperless, and branchless in some of its markets), DBS’s mission is embodied in the slogan “Live more, bank less.”

Gledhill finds that operating in Singapore has distinct advantages. He cites the country’s “advanced IT infrastructure and strong intellectual property regulatory frameworks,” which encourage and protect technological innovation, and he points out that 80 of the world’s top 100 tech companies have a presence on the island. He also mentions Singapore’s highly skilled and highly educated pool of talent. “Together with supportive government initiatives to further Singapore’s digital agenda,” Gledhill says, “we believe we are definitely in the right place to fulfill our digital ambitions.”

The Foundational Years: 2009 to 2014

When Gledhill, Cobban, and the rest of their team joined DBS, they immediately set about changing the culture of the company. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, DBS was determined to differentiate itself from Western banks by emphasizing that it provided, in Cobban’s words, “a special brand of Asian service.” The qualities of this service were embodied in the acronym RED: respectful, easy to deal with, and dependable. The hope was that living up to these qualities would improve the company’s customer satisfaction scores, which Cobban recalls were “rock-bottom.”

Under the umbrella of RED, they created cross-functional teams called PIEs (process improvement events). The goal was to come up with processes that could be implemented within one week and that would address the bank’s biggest service problems — say, the time it took to replace a lost credit card — often by improving speed and eliminating waste. Cobban recalls, “I said, ‘What can you actually change within a short time frame?’ And that was it from an incentive point of view. It made people realize if they put some effort in now, they can see major results. Even to this day, I’m not quite sure how this happened, but we unlocked the enthusiasm, the energy, of the bottom of the company.”

Removing operational barriers lifted the ambition of employees across the organization without the use of incentives.

Notably, the PIEs helped effect a culture shift in the organization by enabling rapid, visible improvements to a wide range of operational processes. Removing operational barriers lifted the ambition of employees across the organization without the use of incentives. “We create a mechanism that anybody can participate in,” Cobban says. “We make it a very low bar to participate, and we did not expect everyone to be successful.”

In addition to improving organizational processes, the new team ensured that the company’s focus was squarely on the customer. In 2009, in what Cobban calls “in hindsight a moment of genius,” the management team invented the measure of the customer hour, a unit of wait time for a customer (a customer waiting for a credit card for an hour equals one customer hour), and used the PIE concept to eliminate as many customer hours as possible. Cobban hoped to be able to take 10 million customer hours out of the bank and ended up taking out 250 million. The process, Cobban says, “was really focused on making the customer’s life better,” a goal that unlike, say, increasing the bank’s profits, gave DBS employees a shared sense of purpose. (Google, Cobban notes, has since adapted DBS’s customer hours concept.) The shift in focus entailed an accompanying shift in the meaning of performance, as the previous measures of success were no longer relevant.

The final innovation was to upgrade DBS’s technological capabilities. “We had to build resilience into our platforms and data centers,” Gledhill says. “Our securities and monitoring operations needed revamping. But more important was the need around insourcing. We built our own technology DNA around the company so that we could really start to look and act more like a technology company. We fixed our application stack and got rid of our legacy systems to build an environment on which we would really start to scale.” The company, which was 85% outsourced in 2009, was 90% self-managed by 2018.

Looking back on the new management team’s early successes, Cobban jokes that “we were so bad, it was easy to improve within that first year.” The team wasn’t yet aspiring to compete with tech companies, but it was laying the groundwork for doing so. Gledhill was still, at that point, “thinking about ‘world class’ as being world-class among banks.” He sees the team’s initial actions, which included experimenting with agile practices, as integral to DBS’s later successes, noting that “our foundational years from 2009 to 2014 were critical building blocks where we fixed the basics to be able to move fast.” The changes to DBS’s approach to performance during this period both responded to and helped drive the company’s digital transformation. Soon, however, the company articulated a new and ambitious goal that led to a major shift in its performance management.

Project GANDALF: 2014 to the Present

Around 2014, Gupta and Gledhill began to see DBS’s competition as tech companies — like Google, Amazon, Netflix, Alibaba, LinkedIn, and Facebook — rather than other banks. They set their sights on joining that pantheon as a world-class tech company. The initials of the tech giants together spell GANALF. The company goal was to add a D to the acronym, for DBS, to spell GANDALF, the wizard of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings novels. “That aspiration, more than any single piece of technology or anything else,” Gledhill declares, “really galvanized people to a completely new level of performance and thinking.” The CIO adds that the company “made it fun as well.”

5 Focus Areas for DBS Bank’s Digital Transformation

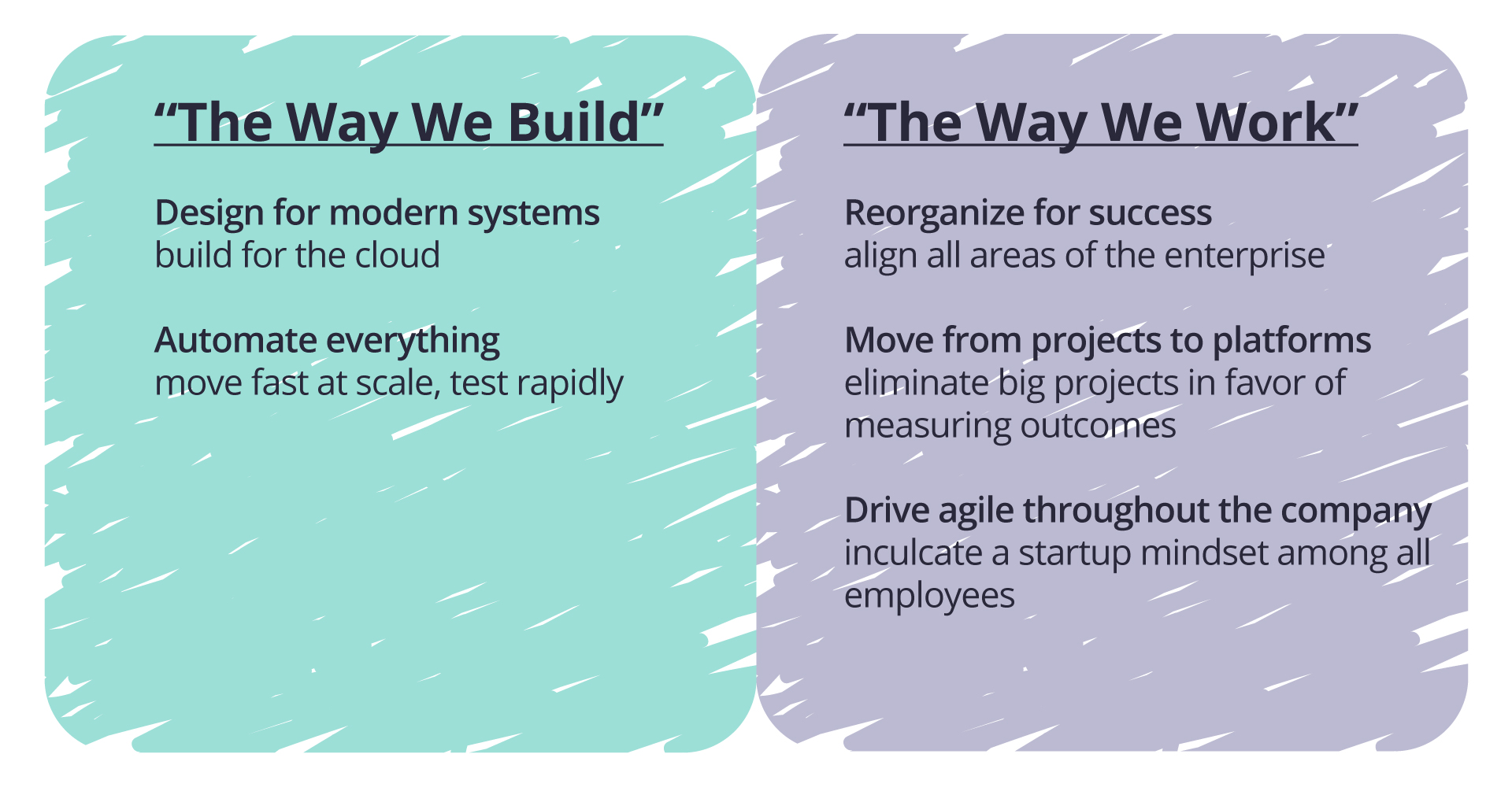

The GANDALF goal led to a shift in the company’s approach to performance management, which DBS explicitly used to drive its transformation toward becoming a digital leader. The company quantified what it wanted to achieve and measured itself continually against its goals through its management scorecard and key performance indicators. The effort was enterprise-wide and aligned the business and technology sides. “It’s a partnership with HR in terms of reimagining the training and tools and the programs that we want to run,” Gledhill says. “It’s working with our marketing folks to figure out how we shape and sell our message. It’s working with the other business leaders to get them on board. So, it becomes a culture shift more than anything else, which has to affect all parts of the organization. Everybody has to shift the way they operate.”

To disrupt itself and join the digital elite, DBS took the following steps:

1. Gave new meaning to “performance.” Once the PIEs had resolved the customer satisfaction problems related to basic issues like length of wait time for customer center calls, they evolved into a set of programs focused more holistically on the customer. Cobban recalls, “We realized we now need to take friction out of the customer journey — it’s a lot faster than it used to be, but still there’s quite a lot of friction. This deep understanding of what customers really need is pivotal to what we built in.” DBS turned to human-centered design thinking to solve customer problems, running more than 500 “customer journey projects.” Employees are invited to create solutions and pitch them to senior staff. That might mean designing apps that don’t consume too much battery power because in a digital age, being “respectful,” part of the RED mandate, means being conscious of the importance of a customer’s battery life.

In 2017, in another move that greatly altered the company’s conception of performance, DBS developed a method for measuring the financial impact of digitization. Called the digital value capture (DVC), the data quickly and quantitatively demonstrated the importance of migrating customers to digital banking. “Through DVC, we noted that, compared to a traditional customer, a digital customer brings in twice the income, with 1.5, 2, and 3.6 times higher deposit, loan, and investment balances, respectively. A digital customer, on average, also costs 57% less to acquire and is more engaged, with 16 times more self-initiated transactions,” Gledhill notes. DVC data served multiple purposes: It created a new mandate for DBS employees, it was shared with investors, and it helped develop the enterprise’s business plan.

2. Used performance management to drive digital transformation. The company uses a balanced scorecard approach to measure performance, and digital transformation now comprises a significant part of the scorecard. As Gledhill explains, “Because we are really pushing this digital agenda, our scorecard has changed. We want to drive people to push digital adoption of the customers. And so 20% of our scorecard — so 20% of the bank’s performance, which ultimately defines how much we get paid — is focused on digital transformation.” The scorecard’s metrics are very precise. Gledhill continues, “We have very specific measures in there about the percent of customers we acquired digitally, about the shift from manual channel to electronic channel, execution for transactions, and how much we engage. So, acquire, transact, engage. Every business and every product within every business has targets about how it has to shift its customer base to those electronic channels. So, the scorecard is very tightly aligned to digital.”

“With most people, it was very liberating because it set an aspiration of something they’d completely, to that point, failed to imagine, and it was fun.”

— David Gledhill

3. Changed the culture that supports performance management. In addition to providing a unifying sense of purpose to the organization, the GANDALF goal has focused DBS on its company culture. Through a process called Culture by Design, DBS has been extremely precise about codifying the culture it wants to establish: one that gives its 26,000-person workforce the feel of a startup. The acronym ABCDE details the characteristics of the culture: Agile (adapting more quickly), Be a learning organization (adopt new ways of approaching the business), Customer-obsessed (understanding customers’ pain points), Data-driven (using data holistically to transform internal processes), and Experiment and take risks (encouraging the 4D process: discover, define, develop, and deliver).

“Once we defined these key characteristics, we started reinforcing them by making aspects of these traits and behaviors a requirement for everyone,” Cobban explains. “We continue to reinforce these characteristics throughout the bank through multiple learning and collaboration programs. We focus on identifying ‘blockers’ to our cultural innovation and set about targeted countermeasures to address them.”

For instance, the company’s meetings, according to Cobban, were frequently ineffective. Problems included “people being late, unprepared, poor agenda, too many people in the meeting, too many meetings generally.” A program called Meeting MOJO was conceived to overcome this particular blocker. Under MOJO, every meeting now has a meeting owner (MO) who in turn appoints a joyful observer (JO). The MO, according to Cobban, ensures that the meeting has a clear agenda, that it starts and ends on time, and that there is “equal share of voice” throughout the discussion. At the end of the meeting, the JO provides feedback to the MO about whether the meeting was a success according to those criteria. “The results have been dramatic,” Cobban says. “More of our meetings start and finish on time, and they now have more structure and engage more attendees.”

“If you give people a sense of purpose and get out of the way, it’s far more powerful than trying to incentivize somebody with money.”

— Paul Cobban

In addition, in 2017, DBS launched DigiFY, a mobile learning platform and online course intended to transform the company’s bankers into digital bankers. The program imparts skills in seven categories: agile; data-driven; digital business models; digital communications; digital technologies; journey thinking; and risk and controls. By the time employees achieve mastery in the three-part course, they are qualified to teach its precepts to their coworkers. Once the company decided it required digital bankers, it methodically set about defining, creating, supporting, measuring, and developing them.

As Cobban explains, all these changes took place within a traditional performance management system; what’s more, they were divorced from financial incentives. “We have not set out to change the culture of performance management directly through compensation. My experience is that it’s not effective in shaping a company,” he says. “Our performance approach is very conventional. We have an annual appraisal process. We have KPIs that we need to meet. If you give people a sense of purpose and get out of the way, it’s far more powerful than trying to incentivize somebody with money.”

Creating Buy-In at the Customer Center

Improvements to the customer center at DBS exemplify the shifts taking place within the organization at large. Beginning in 2014-2015, at the customer center as well as throughout the enterprise as a whole, performance management was used to drive the digital agenda. DBS’s head of customer center Geeta Sreeraman states that while the center, like most contact centers is “a highly KPI-driven environment;” the KPIs were very aligned to the bank strategy. “And our focus was, and continues to be,” she adds, “how do we participate in this whole digital transformation?” The answer was to use technology to engage the staff, improve efficiency, and enhance the customer experience.

A top priority was changing the mindset of the 500-plus customer care representatives. This was accomplished in part by enlisting the employees to collaborate in the creation of the unit’s KPIs. “We don’t want a top-down KPI that doesn’t account for their challenges,” Sreeraman says. The “culture of cocreation,” she observes, resulted in “a lot more buy-in.” Moreover, management regularly reviews and refines the unit’s metrics as the nature of engaging with customers changes. For instance, DBS customers increasingly use chat to handle simple banking issues. As customers turn to phone calls as a last resort to address more complex technical problems, KPIs related to the average time of a phone call are of lesser relevance. Metrics relating to first-contact resolution and customer satisfaction become more critical.

By the time customers do make phone calls, then, there is a strong possibility that they’re experiencing a problem that they were unable to solve using self-service online tools. DBS began using speech analytics not to punish poor performance but to understand both the challenges faced by call center staff and customer pain points. “A lot of our high-emotion calls were because of confusion,” Sreeraman says. If, for instance, the analytic tools revealed that callers were frustrated because they couldn’t access their bank statements, the company specifically trained employees to assist customers in accessing their statements online. (This solution had the added benefit of supporting DBS’s agenda to get its customers to go digital.) Similarly, if an urgent problem arises, the company can figure it out more quickly by registering an increase in negative emotions associated with calls.

Access to data enabled innovations at the customer care center. “We enhanced our internal data capabilities to make sure that we capture real-time data through dashboards,” Sreeraman says, adding that the data also facilitates any “real-time management that we need to do.” As part of having a transparent and open culture, an in-house mobile engagement app called Alive makes performance data available 24 hours a day. Managers can see which employees need additional support and which are in a position to stretch themselves. The app is also used to encourage employees to manage their own performance. They can “benchmark their performance with the rest of the cohort to assess if they are on track to meet their objectives,” Sreeraman says. Employees are encouraged to take responsibility: to self-assess, seek feedback from managers, and set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound) goals. This “self-driven” performance management, she says, is “where we are headed right now.”

Conclusion

As DBS’s recent accolades suggest, the bank has been successful in aligning its performance management system, its KPIs, and its culture with an ambitious digital transformation agenda. Of course, work remains to be done. Gledhill is interested in applying principles of performance management to the company’s teams; he also wants to deploy machine learning and advanced analytics tools to further optimize customer interactions. But as he measures DBS against the tech giants, reflecting on the audacious goal of putting the D in GANDALF, he is confident that the company will continue to make progress. “I would say we’re a long way away from some of the advanced tools and techniques these guys use, but here’s the point,” he reasons. “If this is always your North Star, you will always progressively move closer and closer to it. That’s how we look at it.”

David Gledhill

group chief information officer and head of group technology and operations

David Gledhill is group chief information officer as well as head of group technology and operations at DBS Bank. In 2017, he was the recipient of the MIT Sloan CIO Leadership Award, becoming the first CIO from an Asian company to have won. Prior to joining DBS in 2008, he worked for 20 years at JP Morgan.

Paul Cobban

chief data and transformation officer, technology and operations group

Paul Cobban is chief data and transformation officer, technology and operations, at DBS. He joined DBS in 2009 as managing director for business transformation, and was chief operating officer of technology and operations from 2013 to 2017.

Prior to joining DBS, Cobban held a variety of roles at Standard Chartered Bank, and he also worked at JP Morgan UK as an IT project manager and at IBM as a programmer and project manager.

Geeta Sreeraman

head of customer center, Singapore, technology

and operations

Geeta Sreeraman is head of the customer center at DBS Bank, where she leads a team of 600 employees. Since joining DBS in 2011, she has held various senior positions, from managing relations with regulatory bodies to leading the development of the department. Under her leadership, her group has won many accolades, include Best Contact Centre at the Annual Contact Centre Association of Singapore Awards. She started her career as a relationship manager for Citibank India.

Banking On Technology-Enabled Performance Management

By Peter Cappelli

The DBS Bank example is a good illustration of how to pull off organizational change, especially a big one. The key is to use many different levers to get employees to behave differently. In this case, performance management is one of those.

It is useful to think of organizational change as similar to trying to get an individual employee to behave differently, but you have to do it at scale. There are all kinds of reasons we keep doing things the same way, but the most important is arguably that change is both unsettling and, in many cases, risky, especially if what we have been doing has been working pretty well for us.

It helps to have a powerful need for change. Some people refer to this as a burning platform — a pressure that is big enough that we cannot simply ignore it. DBS wasn’t failing; it just wasn’t very good. The pressure had to come from someplace else.

The success of DBS seems to have come from two initiatives. The first was empowerment. We’ve long known that employees can be engaged to work hard and creatively on projects for which they are responsible and that they own. The Singapore work culture is generally quite top-down, so the decision to empower teams to take on projects is more radical than it sounds. I suspect the employees responded to it with even more energy than they might elsewhere.

The second initiative relates to performance management, specifically the creation of measures of success. It is hard to engage people in anything if they do not know how they are doing, and it is especially difficult to improve if you cannot measure whether you are doing better: Imagine trying to improve your golf game if you went to the driving range and could never see where the ball went. The truly innovative initiative at DBS was to create a measure of performance — hours of customer time — that had face validity (we can see why it is good for business and for customers to bank faster), will stay in place over time, and is comparable across parts of the bank.

Paul Cobban says that the bank’s performance appraisal system is very conventional, but the management team did make changes in it that drove behavior in a different direction. That began with new organizational measures, a balanced scorecard, and new measures of individual behaviors that the team wanted employees to execute. We should not underestimate the importance of training on those behaviors because a big cause of resistance to change is employees who aren’t sure whether they will be able to hit the new goals, so they often do not try. Good training goes a long way toward taking that fear away.

Even with all these efforts, organizational changes typically fail. They are working at DBS in part because the leaders smartly let the new practices drive culture changes and aligned efforts to move employees in a new direction. DBS leaders provided a compelling vision of becoming a digital company, empowered employees to act on that vision, measured how they are doing, and gave them the skills to succeed. As with any successful change, it is a lot more work to make it happen than it sounds from a story. The key element here is leadership commitment: Put time and sustained resources into the effort and see it through to a conclusion.

Peter Cappelli is the George W. Taylor Professor of Management at The Wharton School and director of Wharton’s Center for Human Resources. He is also a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, served as senior advisor to the Kingdom of Bahrain for employment policy from 2003-2005, and since 2007 is a distinguished scholar of the Ministry of Manpower for Singapore.