Information Orientation: People, Technology and the Bottom Line

Two global banks, comparable in many ways, differ in their business performance. The more successful bank is more effective in its use of information. A coincidence? Not likely.

Companies, such as these banks, are still struggling to understand how to put information to work so that it improves business performance. Two information-based management disciplines — the information-technology field and the information-management field, which involve librarians, records managers and Web-site content managers — have put more emphasis on creating systems and processes to store or classify information than on improving the way people behave with information. After spending billions of dollars on information technology, it’s still difficult for senior executives to connect their company’s technology investments to its business performance. More often than not, this technology-centered viewpoint has not encouraged more people-centered management activities aimed at improving behaviors and values for more effective information use.

If there is a starting point for improving how businesses use information, it’s in a perception many senior managers share: Companies must do more than excel at investing in and deploying IT. They must combine those capabilities with excellence in collecting, organizing and maintaining information, and with getting their people to embrace the right behaviors and values for working with information.

Is this notion right? How does the interaction of people, information and technology affect business performance? These questions led a team of 10 researchers and staff from the International Institute for Management Development, sponsored by Andersen Consulting, to conduct a 2-1/2–year international research effort to understand how senior managers perceive the relationship between business performance and three information capabilities — IT, information management, and people’s behaviors and values pertaining to the use of information.

We studied 1009 senior managers — nearly 60% of whom were CEOs, executive and senior vice presidents and general managers/directors — from 98 companies operating in 22 countries and 25 industries (see “Research Methods”).

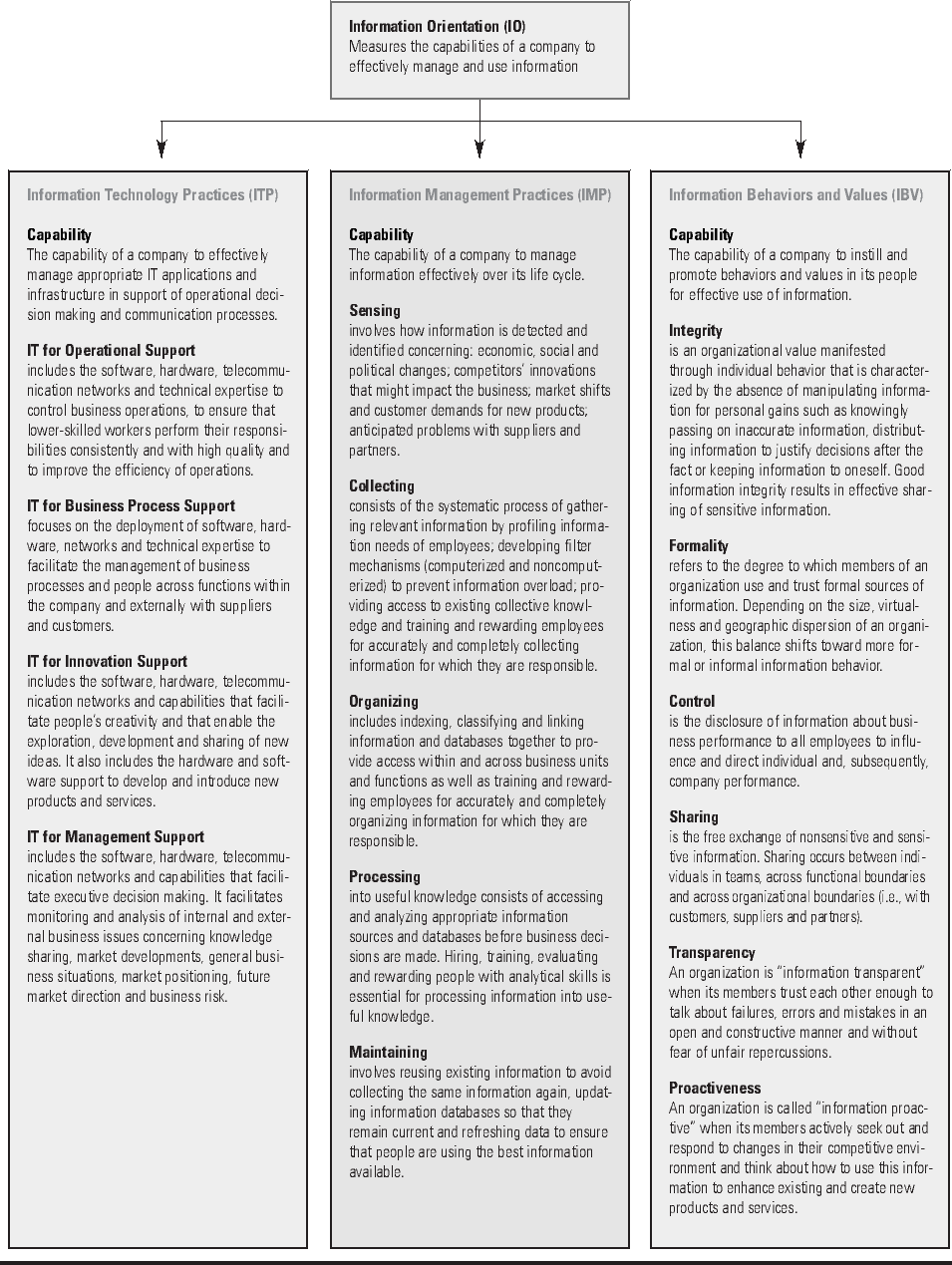

Results of the study are twofold. First, we used accepted psychometric techniques (see “Research Methods”) to model the thinking of those 1009 senior managers on “what being good at using information” means. From these results we captured their “mental model” confirming the existence of three “information capabilities,” broad sets of skills, behaviors and values — consisting in total of 15 specific competencies associated with effective information use (see “How Managers View Effective Information Use”). Further testing using a confirmatory factor analysis — a way to show that ideas are consistently perceived by a group of people — showed that senior managers viewed these three information capabilities as components of one higher-level idea we call “information orientation,” or IO, which measures a company’s capabilities to effectively manage and use information.

How Managers View Effective Information Use

Our statistical evidence suggests that strong IT practices, competent management of information and good information behaviors and values individually do not result in superior business performance.

Results from our study indicate that IT practices, management of information and information behaviors all must be strong and working together, if superior business performance is to be achieved (see “Research Methods, How We Analyzed the Survey Data”).

This link between IO and business performance, which we examined using a statistical technique called structural equation modeling (see “Research Methods”) is more powerful than a simple correlation. Our results indicate that IO does indeed predict business performance. From a practical perspective, therefore, IO represents a measure of how effectively a company manages and uses information. An organization must excel at all three capabilities (in essence, having “high” IO) to realize superior business performance.

Of course, even high IO cannot always guarantee higher business performance. Extended external shocks outside a company’s realm of influence can have a negative effect on business performance despite a high IO. For example, the Asian financial crisis had a devastating effect on the business of one European specialty chemicals company we studied despite its very high IO. And reinsurance companies often face the serious negative performance effect of repeated natural disasters.However, companies with high IO may have an easier time recovering from these shocks.

What are the managerial implications of these findings? Companies that develop the information capabilities found in companies with a high IO can improve their business performance.

Information Orientation: A Measure of Effective Information Use

Information orientation measures 15 competencies within the three basic information capabilities that managers associate with effective information use (see “How Managers View Effective Information Use”).

- Information Technology Practices (ITP). A company’s capability to effectively manage information-technology (IT) applications and infrastructure to support operations, business processes, innovation and managerial decision making. This is the realm of software, hardware, telecommunications networks and technical expertise, supporting everything from the tasks of lower-skilled workers to the creation of innovative new products and the analysis of market developments and creation of strategy.

- Information Management Practices (IMP). A company’s capability to manage information effectively over the life cycle of information use, including sensing, collecting, organizing, processing and maintaining information. This group of skills includes identifying and gathering important information about markets, customers, competitors and suppliers; organizing, linking and analyzing information; and ensuring that people use the best information available.

- Information Behaviors and Values (IBV). A company’s capability to instill and promote behaviors and values in its people for effective use of information. They include integrity, formality, control, transparency, sharing and proactiveness. Some examples are ensuring that information is accurate and not manipulated for personal gain, creating a willingness to share information with others and encouraging employees to seek out information and put it to new uses.

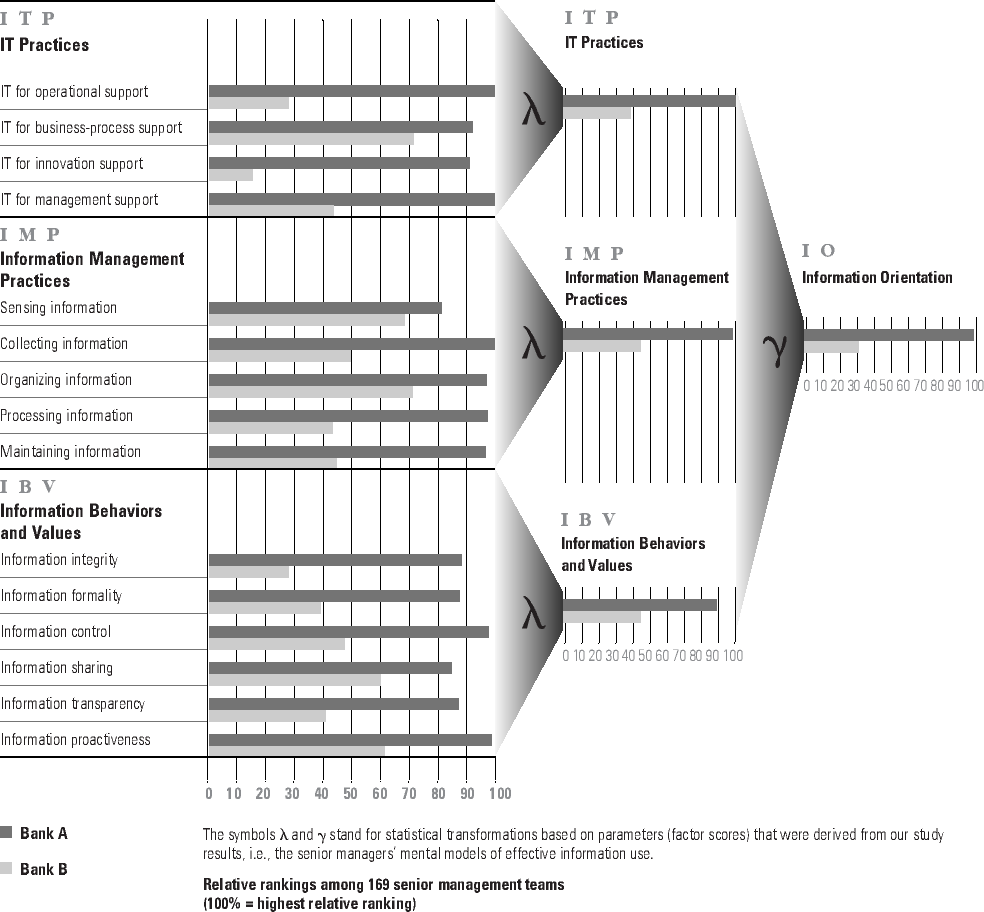

To illustrate the differences between companies with high IO and low IO, we compared how senior managers of two different retail banks evaluated the 15 dimensions of their own organizations’ IO.

For this purpose, we aggregated the responses of our sample of 1009 managers to their senior management teams. We treated each team as one business unit, for a total of 169 business units. Then, we looked at the relative rankings of each of these 169 senior management teams (on a percentage scale of 0 to 100%). On the basis of these rankings, the research team identified two companies in the same industry — one that had rated among the highest on IO and one that rated in the lower third. On-site interviews revealed contrasting practices at these high- and low-IO companies. The guidelines offered below, however, are drawn from the entire study, not just the two banks.

Achieving High Information Orientation

The retail banking units of two of the world’s top global financial services companies illustrate the difference between high- and low-IO companies. Bank A had an IO ranking of 99%, whereas Bank B ranked only 31% (see >“Two Banks, Two Information Capabilities”). These two companies faced similar business challenges within their retail banking operations over the past five years; their senior managers, however, chose to follow two different paths to achieve performance improvements in this highly competitive industry, reflecting fundamental differences in how senior managers saw the role of effective information use for value creation.

Two Banks, Two Information Capabilities

By the late 1990s, Bank A had doubled its business volume in a saturated banking market and had increased its earnings per share by 131% and market capitalization by 400%. Coincidentally, Bank A had succeeded in attaining high IO — not by massive investment in new IT systems, but through the synergy created by adopting a people-centric view of information use.

During the same time, Bank B struggled with declining market share, while losing its leadership position following the merger of its two largest competitors. In 1998, the unit continued to register a loss of $190 million.

Yet during the mid-1990s, these two retail-banking units faced similar challenges. Representing less than 20% of their respective company assets, both organizations experienced declining growth opportunities in saturated, branch-based national markets. Intense competition and frequent mergers characterized the industry. While insurance, investment and equity-trading companies broke into traditional retail banking, small start-ups, often Internet-based, conquered important market niches. The profitability of both banking units lagged that of leading competitors.

In this context, senior managers in both units drew up new business strategies. In 1993, Bank B expanded its market share by merger, making it the largest bank in its headquarters country. Over the next four years, its senior managers focused on cost cutting through three restructuring and downsizing programs aimed at integrating and streamlining the operations of the two merged banks. Growth initiatives were postponed until the restructuring was complete. The program resulted in a reduction in personnel expenses by 10%, improvement in the cost-income ratio from 103% to 85% and a reduction in domestic head-count by 21%. Improving the use of information focused almost exclusively on process integration of the two banks’ IT systems.

Senior managers at Bank A took a different strategic approach. “The bank’s morale, its profitability and credentials had to improve,” described one executive. “We needed a program to unleash the bank’s hidden value.” This program would focus on setting ambitious growth targets, achieved through an aggressive cross-selling campaign not just on a local, but a regional and global level. At the heart of this campaign was the development of an information strategy that focused on the development of appropriate IT tools for improved decision making at all levels of the company, processes for the effective management of customer and product information, and employee and manager training to ensure the appropriate use of information within an open, action-oriented company culture.

Senior managers at Bank A (high IO) and Bank B (low IO) had different views of their businesses, and each used information differently. The result was different IT practices (ITP), information-management practices (IMP) and information behaviors and values (IBV).

IT Practices of Companies With High IO Levels

Our IO model identifies four levels of IT support: IT for operational support, IT for business-process support, IT for innovation support and IT for management support. The IO ratings of Bank A and Bank B are vastly different for the IT practice capability: While Bank A ranked in the top spot at 100%, Bank B had a relatively low rank of 39% (see “Two Banks, Two Information Capabilities”).

During the 1990s, Bank A invested significantly in building a simple but elegant IT system that enabled branch representatives to merge greeting, servicing and cross-selling to customers into one act. The process of greeting the customer allows the branch representative to call up the customer account. The account provides the following information: demographics (the customer’s socio-economic profile), product usage, segment profile and all previous interactions with the bank, regardless of channels used, including ATM use, call center and Internet banking.

The rankings indicate that Bank A excels at IT for operational support (with a top rank of 100%) —managing hardware and software to improve operational efficiency. At the center of Bank A’s growth strategy is a belief that the people at the branch are the cornerstone of all bank activities. “Our head offices and our regional offices exist only to support the branches,” described one senior manager. For operations support, IT is therefore focused on making branch employees more productive through the standardization and centralization of the back office, which gives staff more time to spend with customers. Early on, Bank A’s IT platform fully integrated all three banking channels — branch, telephone and Internet — enabling staff to pull up customer and product information from any of the company’s branches and channels. This also allows a service representative to see the financial activities of each customer and allows the customer to see the financial-services company as one entity — a key element of the cross-selling system.

However, it is in the high rankings for IT for innovation support (91%) and IT for management support (100%) that Bank A shows its competitive edge. Information technology for innovation-support applications allows customization, tracking of potential new customers and identification of internal business opportunities. These applications allow branch managers to keep abreast of trends for product innovation and segment marketing. Information gathered through these applications is fed into existing management-support systems to speed new product development and future strategy formulation.

Most importantly, the customer support system provides flexible decision-making support at all levels of the company. Managers can actively monitor on a daily and monthly basis changes in customer base, product sales, business-performance goals, risk assessments and customer buying behavior. This arms senior managers with the appropriate information to set future branch business strategies.

In contrast, Bank B’s rankings tell a different story. Over the past five years, Bank B has focused the majority of its resources on IT for business-process support (with a rank of 72%), while bogging down the conversion of two merged banks’ IT operational-support systems (with a rank of 29%). The IT department of the dominant bank in the merger attempted to impose a clone of its operational IT platform onto the acquired bank. Because of very different operations and products, this conversion went very slowly; branch employees had to work for several years with two separate platforms and data centers. Additional restructuring of Bank B’s business in 1996 again tied up resources. By 1999, 80% of the two systems had successfully merged; however, channels remained fragmented. Product managers had inadequate decision-making tools and suffered from information overload. Customer-relationship managers complained about the three-month lag in obtaining changes to customer information and relied instead on their own personal information systems. Finally, senior managers blamed “IT problems” for underperforming areas of their unit. They consistently perceived that IT was adding little to innovation (low IT innovation support at 16%) or managerial decision making (at 44%).

What can we conclude from the comparison of Bank A and Bank B? High-IO companies excel at building systems that support flexible decision making by managers and employees. Bank A’s goal for IT systems development has been a straightforward one: Provide the people in the branches (“the bank’s cornerstone”) with the necessary tools to improve their decision capabilities by analyzing risk, monitoring market position, forecasting changes in business conditions and providing information for proactive marketplace responses. The following guidelines, culled from IT practices at Bank A and other high-IO companies studied, can help companies move toward a higher level of IT practice.

IO Guideline 1: Focus Your Best IT Resources on What Makes Your Company Distinctive

In most companies, the time, attention and expertise of top-quality IT people are in short supply. Companies with high levels of IO understand this. They focus their best IT resources on information capabilities that make them distinctive. They out-source the rest. The high-IO company leverages IT to create new products and services and improve management decision making. In contrast, companies with low IO dissipate their best IT resources on the functions that are necessary for the companies to operate. For these companies, there never seems to be enough time or IT people to devote to what is important, since the pressures to do what is necessary seem to be forever urgent.

For example, at Bank A, IT applications that are considered essential to compete are kept in-house and implemented by the most talented and experienced IT staff. Applications that are necessary to operate, however, are outsourced.

How do managers at Bank A know how to allocate IT resources? Each IT resource investment is sponsored and discussed across the bank’s key business areas. The managers in those areas decide together whether or not investments are strategic. In contrast, Bank B has been trying to “fix” its IT for operational support for years. It has kept its nonstrategic IT issues in-house. This has left Bank B with few IT resources to invest in new product development or better management decision making. Like other companies with low IO that we have seen, Bank B’s managers lose sight of which information capabilities could make them distinctive. In such companies, the best IT professionals often leave for more interesting work elsewhere.

IO Guideline 2: Effective IT Operations Support Effective Business Processes, Which Then Provide Information for Decision Making

For many companies with low IO, poor information for management support of strategic and tactical decisions is a direct result of ill-designed business processes. Senior managers in these companies complain that their decision-support systems do not really enable decisions. In many ways, these managers have put the cart before the horse. We observed manufacturing companies that do not focus on improving their supply-chain processes, yet they expect to have IT systems that will process information for operational and management planning, financial management or longer-term sensing and forecasting of customer demand. These expectations are unrealistic. Similarly, service companies must integrate business processes with well-thought-out operational systems before they can use IT to support the high-quality information they need to make decisions.

Companies with high IO, such as Bank A, have focused on getting IT support for key processes in place to manage customer and product information for sales support, cross-selling and customer service. From this base, they have developed sophisticated systems and databases for management support, product innovation and business-strategy formulation.

IO Guideline 3: Good IT Practices Can Uncover New Business Opportunities and Lead to Innovative Management Actions

A company with high IO benefits not only from tying its IT practices closely to the way it creates business value, but also from new business opportunities and management initiatives. It is able to do better things with IT inside the company and for customers. As companies seek to transform their business with e-commerce projects, being good at IT is critical. In the case of Bank A, IT is seen as directly influencing business strategy. “IT enabled the bank to pursue its strategy of value creation,” commented the bank’s chief information officer. Currently, Bank A is using these capabilities to develop direct telephone and Internet channels to supplement its traditional branch business. Superior IT practices also continue to play a critical role in its global expansion and merger strategy. Its IT model is considered one of its strongest capabilities and is now being exported and replicated by numerous global strategic partners. Bank B has also recently developed an Internet channel, but it faces considerable customer-service challenges because telephone, branch and Internet interfaces remain incompatible.

The Information-Management Practices of High-IO Companies

The IO model identifies five separate phases of information-management practices: sensing, collecting, organizing, processing and maintaining. Bank A and Bank B show marked differences in rankings —Bank A excels at information-management practices (99%), while Bank B is ranked at only 45%.

Managers at Bank A see the active management of information as a critical aspect of everyone’s job and an enabler of their business activity. Branch representatives are taught how to record their observations about customer demands for new products in the customer-support system (putting the bank’s relative ranking at 50%). Market shifts in customer preferences are monitored by data-mining applications. Competitors’ innovations and leading practices are monitored by people within a commercial development department who travel around the world visiting interesting companies, including those outside the financial-services industry.

Bank A pays special attention to training its employees to collect (100%), organize (97%) and process (98%) information about customers, products and performance. For example, the controlling department alone employs 10 full-time people dedicated to training and supporting Bank A’s employees in the use of new product, financial and operational information. Branch representatives are taught how to interpret acceptance or rejection of product offers, as well as how to comment on each conversation with a customer.

Bank A’s aggressive, yet focused, use of information for cross-selling places great pressure on the branches to have refreshed information about products and customers each day. Continuous updating of eight customer segments further broken down into five service types requires well-formalized information valuation and reuse practices. Special attention is paid to information maintenance (97%) because branch reps cannot offer the same product to a person two or three times without offending them.

Bank B’s IO rating paints a different picture. Senior managers believe their company is relatively good at sensing changes among their customers, competitors, suppliers and partners (67%). They are also good at organizing the existing information (71%). Unfortunately, their fragmentation of systems and structure prevents them from effectively valuing, indexing and collecting (50%) potentially valuable information. With fragmented information collection, processing (44%) or maintenance (47%) also suffers. The result: Customer representatives do not have access to detailed customer information other than size of account balances and transaction histories. Data duplication and administrative-task redundancies further burden individual units: 75% of their time is spent on administration. Managers experience information overload and make decisions based on a gut feeling, rather than analysis.

What can we conclude from these examples? Effective information management must be instilled in a company’s people. Good sensing and information-valuation and information-processing practices are critical elements of the high-IO company. The following guidelines can help managers think about how to move their companies toward better information-management practices.

IO Guideline 4: Companies With High IO Actively Manage All Phases of the Information Life Cycle

Companies with high IO view information as having a life cycle with discrete valuation points. These valuation decisions are made continuously as people work, and they are reinforced through communication, formalization of best practices and on-the-job training. New information sensed from the competitive environment is first valued for its fit with current and future information needs; if individuals qualified or trained to evaluate the information’s relevance for business needs determine that the information has high value, then information practices must permit easy collection and organization for decision making; after processing, information must be updated or discarded. High-IO companies, like Bank A, understand the importance of each of these practices and know that inadequate attention to one practice can disrupt the cycle.

IO Guideline 5: Managers and Employees Must Develop an Explicit, Focused View of the Information Necessary To Run the Business

Good information management should constantly focus on the decision contexts of managers and employees. Because it is people who use information, thinking about information needs should be part of everyone’s job. Leaving the responsibility for good information management to information specialists or IT staff may give temporary peace of mind. However, it’s a problem if people in all departments are not motivated to treat their “information responsibilities” as carefully as their other work responsibilities. In short, information responsibility should mean information accountability for everybody (see Marchand, Davenport and Dickson, 2000).

IO Guideline 6: When People Do Not Understand the Business, They Cannot Sense the Right Information To Change the Business

People can sense information effectively only when they understand what drives a company’s business performance and how they personally can help to improve performance. A company that provides information to employees to help them understand not only what they are doing, but also why they are doing it, is better able to focus on relevant business information. Companies with high IO constantly tell their managers and employees about external forces influencing business performance. This common sense of purpose fosters an environment in which people begin to look beyond their own jobs and become concerned about the information needs of others. Sensing is enhanced and information-valuation assessments become more precise.

Information Behaviors and Values of High-IO Companies

The IO model identifies six information behaviors and values: integrity, formality, control, transparency, sharing and proactiveness. Bank A’s information behaviors and values rank at 90% among the companies we surveyed. The rankings are similar to Bank A’s high IT practice and information-management practice rankings, while Bank B’s information behaviors and values rank is 44%.

A company with low IO, such as Bank B, may instill some, but not all, requisite behaviors and values. For example, Bank B shows relatively higher rankings for sharing (60%) and proactiveness (62%) but ranks relatively low on the other behaviors and values. These gaps in people’s mind-sets and behaviors — when coupled with additional deficiencies in information-management practices and IT practices — may result in lower business performance.

In contrast, Bank A’s rankings show a strong focus on all six information behaviors and values. Clearly, people matter to this company. As a corporate value, integrity is taken seriously (at a ranking of 88%). In all branches, there is a no-tolerance policy for people who manipulate information for personal gain, pass along inaccurate information, distribute information to justify decisions that have already been made or knowingly hoard information.

The integrity of information is especially important to ensure that people use and improve the formal customer-support system (87%). People’s willingness to use and improve formal sources of information at Bank A reduced the time wasted on re-collecting, reanalyzing and double-checking information.

People’s reliance on and access to formal information sources at Bank A help managers to provide employees with clear information about how their own performance relates to team and branch performance. The data show that information control, at a rank of 97%, is a key element in Bank A’s information behaviors and values. Why is control so important? “We cannot achieve our goals without a trusting atmosphere. We are conscious about having open dialogues with our employees and sharing information about the bank’s financial results and their team and individual performance,” commented the head of Human Resources. Bank A is so convinced that attention to team performance makes the difference in promoting openness that it encourages competition among teams of different branches. The winning branch receives a special prize and bonuses are paid to all its employees. Within this context of team spirit, transparency is encouraged (rank of 87%) within branch units so that mistakes and errors can be identified and learned from constructively. At Bank A they like to call mistakes and failures “future opportunities.”

Managers at Bank A are also convinced that in a working environment in which people understand how individual and team performance relates to company performance, people are more likely to share and use information in ways that benefit others. At Bank A, information sharing is not left to chance — it is an actively monitored activity (ranked at 85%). At the branch level, retired employees act as mystery shoppers and check to see that information about customers and products is shared with people in branches and with customers. Regular customer surveys monitor the bank’s ability to provide accurate customer information. Senior managers also make a conscious effort to recognize and show appreciation to those demonstrating leadership in information sharing. “The managers who share more information are the bank’s most respected employees,” commented the head of the retail-banking unit. “We also monitor sharing through performance indicators. We realize quickly when information sharing within a branch does not occur because it starts to underperform.” These indicators trigger not only the development of a recovery plan with the branch manager, but also an increase in teamwork training for all branch employees.

Finally, and most importantly, the data indicate that managers at Bank A know that effective information use ultimately depends on their ability to create and motivate information users’ proactiveness. This knowledge ranks the highest (at 99%) relative to all other information behaviors and values at Bank A. Bank A not only trains people for this behavior, but also understands that the cumulative effect of high integrity, formality, control, transparency and sharing the “right attitude” is a proactive workforce able to respond quickly to customer needs and to think about how to use company information to create or enhance products and services. To a great extent, the success of their aggressive cross-selling strategy depends on it.

This people-centric view of information use has created a powerful working context: Customer representatives are given clear performance targets and empowered with quality information; they are taught how to sense, record and analyze information from their customer contacts for use by other employees, and they are given the authority to make proactive, informed decisions.

Bank B clearly does not have a people-centric view of information use. There has been no formal corporate effort to develop appropriate information behaviors at any level of the organization. Integrity ranks very low at 28%. Lack of access to formal information on an outdated IT system that is not user-friendly forces people to rely on informal sources primarily from within their own functional boundaries. Unclear performance criteria and a focus on individual rather than team measures reduce the willingness of people to share information for the benefit of others.

Restructuring and cost-cutting programs have reduced the willingness of people to be open with information. Finally, branch managers have found it difficult to encourage proactive cross-selling strategies with customer representatives in branches, blaming the difficulty on “cultural biases” within the employee base.

The following guidelines can help managers think about how to move their companies toward more proactive information use and better information behaviors and values.

IO Guideline 7: Do Not Compromise on Information Integrity

In organizations, integrity develops trust among people by defining boundaries within which they can legitimately use power and influence. In an organization characterized by integrity, people believe in and share a set of key principles that outline appropriate conduct in the company — they feel they have a duty to act within the accepted boundaries of ethical and appropriate behavior. People with integrity will present what they know about reality candidly and fairly by not hiding bad news or glossing over important but discomforting facts or concerns.

IO Guideline 8: Team-Based Performance Information Creates Openness and Improves Information Sharing

The type of performance measures and indicators used in a company counts. Bank A illustrates how team-based performance information can create more openness and information sharing. Companies using only individually based measures may compromise on sharing and openness by creating overly competitive working environments. However, performance indicators tied only to an overall business measure —such as EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) —may not give enough information to provide adequate information control.

IO Guideline 9: People Who Understand the Business and Are Informed Will Be Proactive

The process of openly sharing performance-based information inside a company creates powerful support for employees and managers to seek new ideas and information or apply information in new ways. Proactive behavior is not an accident: High-IO companies build it up systematically over years, not only through training, but by reinforcing the behaviors values that lead to (or create) this disposition in people — integrity, formality, control, transparency and sharing. This allows high-IO companies to rely on a broader base of employees with a disposition to act to create business value every day in many small —and not so small — ways, rather than depend on the occasional heroic efforts of a few.

IO Guideline 10: Managers Can Influence Some Behaviors More Easily Than Others

Some behaviors and values, such as integrity and transparency, are more rooted in the individual person than others, such as control, sharing and formality. Managers must be aware that not all behaviors of subordinates and peers can or will change at the same time just because managers “think” that they have taken appropriate steps.

Changing mind-sets, behaviors and values is never easy. Building integrity, transparency and trust requires not only managerial action, but also employee acceptance. Managers have to persuade doubters that their steps to improve information behaviors and values not only are genuine, but will also take hold in the company’s ways of doing business over time. The best way managers can accomplish this is by mirroring these behaviors themselves. Nonetheless, many companies will need months and years of focused efforts before all information behaviors and values have been turned around.

Conclusion

The rush to e-business today only emphasizes a basic fact of organizational life: All business organizations — be they dot-coms or established companies —require excellent information capabilities. Companies that incorporate a people-centric, rather than merely techno-centric, view of information use and that are good at all three information capabilities will improve their business performance.

Leading your company on a journey to achieve high IO and attain superior business performance takes hard work, persistence and personal commitment. To undertake the journey, you will have to develop the right mind-set about effective information use in your business. Lead and inspire your people along the way — your company will be better for it.