Knowledge Management’s Social Dimension: Lessons From Nucor Steel

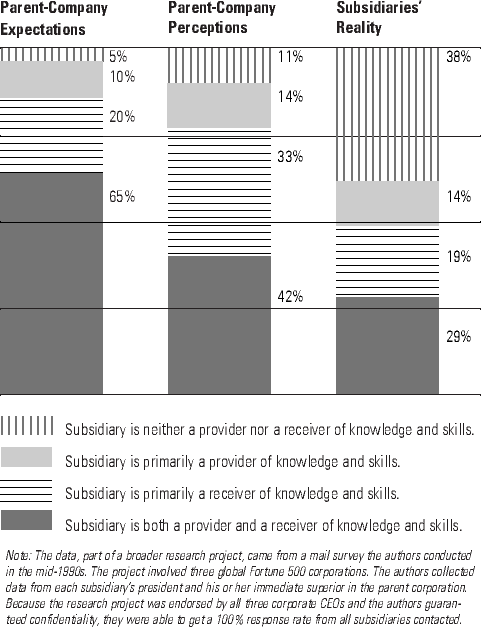

A gap exists between the rhetoric of knowledge management and how knowledge is actually managed in organizations. There is widespread awareness of the economic value that creating and mobilizing intellectual capital can unleash. Yet, for most companies, the reality rarely matches the potential. As the CEO of a commercial-services company lamented in an interview, “We provide pretty much the same services in every location. But my regional managers would rather die than learn from each other.” Our research suggests the CEO’s experience is not an isolated one. In fact, too often, actual knowledge sharing doesn’t just fall below executives’ expectations; it doesn’t even match their perceptions about the extent to which knowledge is being shared within their organizations. (See “The Potential vs. the Reality of Knowledge Sharing: Survey Results from Three Large Global Corporations.”)

The Potential Vs. The Reality Of Knowledge Sharing: Survey Results From Three Large Global Corporations

Building an effective social ecology — that is, the social environment within which people operate — is a crucial requirement for effective knowledge management. Nucor Corp., the world’s most innovative and fastest-growing steel company for the past three decades, is a case in point. The company’s phenomenal success cannot be explained without examining the exemplary social ecology that Nucor has created for accumulating and mobilizing knowledge. By adopting a similar framework, any company can convert itself into an effective knowledge machine.

The Central Role of Social Ecology in Knowledge Management

Because all knowledge starts as information, many companies regard knowledge management as synonymous with information management. Carried to an extreme, such a perspective can result in the profoundly mistaken belief that the installation of a sophisticated information-technology infrastructure is the be-all and end-all of knowledge management. Effective knowledge management depends not merely on information-technology platforms but more broadly on the social ecology of an organization.

Social ecology refers to the social system in which people operate. It drives an organization’s formal and informal expectations of individuals, defines the types of people who will fit into the organization, shapes individuals’ freedom to pursue actions without prior approval, and affects how people interact with others both inside and outside the organization.

References (7)

1. For an extensive discussion of the pathologies that bedevil companies in utilizing knowledge within or outside their corporate boundaries, see also:

J. Pfeffer and R.I. Sutton, “The Knowing-Doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge Into Action” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).