Viewing Brands in Multiple Dimensions

When General Motors Corp. tried to revive its Daewoo car division in the United Kingdom early in 2005 by rebranding it with the Chevrolet badge, it ran into big trouble. Car buyers had difficulty linking the iconic American brand — immortalized in countless movies, celebrated in numerous songs and enjoying more than 90% brand awareness — with the low-priced Korean autos. The result was falling sales and the resignation of the chief executive of GM’s operations in the United Kingdom.1 Moreover, the Chevrolet brand itself deteriorated significantly in the 2006 J.D. Powers & Associates annual satisfaction survey in the United Kingdom, ending up ranked just ahead of troubled automakers such as Fiat S.p.A. and far behind other American makes such as Ford Motor Co. or other Korean brands like Hyundai Motor Co.

In another instance, marketers at Nestlé S.A.’s British operations chose to capitalize on the brand equity of a much-loved confection, the historic KitKat bar. In a bid to boost lackluster sales in 2003, the marketers launched brand extensions in multiple flavors such as Blood Orange, Lime Crush and Christmas Pudding. Although there was temporary interest in the new launches, the experiment failed spectacularly. KitKat’s overall U.K. sales fell by 18% in the two years prior to April 2006.2 Nestlé has since dropped almost all of the unusual flavors.

These vignettes illustrate the actions of managers who fail to understand all the dimensions of a brand. Specifically, few managers grasp the fact that perceptions of a brand can and do change dramatically over time and from one social or cultural setting to another. Indeed, companies cannot so much manage a stable brand image as negotiate an evolving one — meaning that their managers must redefine the brand discourse in more flexible language.

The Heart of the Problem

At root, brands are symbols around which companies, suppliers, supplementary organizations, the public and, indeed, customers construct identities.3 It is a given that branding is a critical issue for marketing and sales; strong brands facilitate the repeat purchases on which sellers rely to enhance corporate financial performance. Brands also ease the introduction of new products and assist promotional efforts. And they enable premium pricing as well as the market segmentation that makes it possible to communicate coherent messages to specific target customer groups. Marketers are rightfully obsessed with brand loyalty, which is particularly important in categories such as food products or household cleaning products where repeat purchases foster profitability.

Too often, though, brands have been seen solely as “instruments” of management. This simplistic but prevalent view assumes that marketing or brand managers own their brands and that these brands are tools that, if managed properly, can help the organization attain its objectives. Conversely, in some instances, brands have become ends in themselves — or at least ends for the people who manage them — overlooking the fact that their critical role is as a means to an end.

Thus, what Theodore Levitt famously calledmarketing myopia (a narrow definition of business focused on what the company produces) has been augmented or replaced bybranding myopia, where the brand becomes an end in itself. As the Daewoo and KitKat stories illustrate, such perspectives leave their proponents exposed to the risks posed by changing aspects of consumption, technology and competition.

Nevertheless, for all of their influence and contrary to popular marketing rhetoric, the whole world is not in love with brands. Today, a vigorous antibranding movement4 reflects powerful antiglobalization activism and broader resistance to the offerings of large corporations. The challenges posed to companies by such changes in the business environment — an environment in which brands are no longer solely the prerogative of marketing — are likely to require refinement and extension of the ideas by which brands are conceptualized and managed. The concept of the “brand manifold,” which will be discussed later in this article, takes a step in that direction.

Revisiting the Broader Implications of Brand

During the 19th century and for much of the 20th, a company’s value, notionally represented by the net book value of assets on the balance sheet, was heavily dependent on tangible assets such as plants and equipment. However, in recent years, the gap between market capitalization and net book value has increased to enormous proportions, driven largely by the importance of intangible assets. Key elements of these so-called “soft” assets are a company’s brands — both for the company as a whole and for its separate products — and the customer and other relationships embedded therein. Indeed, research links both price premiums and market share to brand equity.5 Observers of financial markets are often intrigued to learn that the ratios of market capitalization to revenues can range from as high as 20-to-one for companies such as Microsoft, Nokia and Louis Vuitton, to as low as 0.6-toone for companies such as Ford, Volkswagen and Hertz.

Stakeholder assessments of a brand depend both on mediated perceptions and on direct experience — that is, information about a brand (brand communications) and direct interactions with a brand (brand embodiments). Brand communications comprise information from the company, customers and other stakeholders. Brand embodiments constitute the brand as experienced through products, employees, suppliers, channels, other third parties and consumers — what some call customer touchpoints. If we distinguish between factors that are and are not directly under the organization’s control — designated internal and external, respectively — we see that stakeholder perceptions of the brand depend on both internal and external communications and embodiments. Managers must therefore understand and manage meanings of the brand among both internal and external stakeholders.

In recent years, there has been vigorous debate on the role of brands in the changing marketplace,6 giving vent to perspectives that range from the radical7 to the refining.8 One aspect that has been a hot topic for discussion concerns the extent to which branding efforts are aimed at current and future employees in an attempt to deal with the consequences of permanent shortages of knowledge workers. The topic has been particularly relevant to industries such as energy and utilities, which are now threatened with significant losses of skills and institutional memory as baby boomers leave the work force.

Given such significant business factors and recognizing the escalation of competition worldwide, it is clear that the stewardship of brands becomes a strategic issue that shapes the future of a company as a whole rather than only being the work of marketing decision makers. It becomes a strategic initiative and the collective, collaborative work of the executive team. Indeed, branding may already have become too important to be left to marketers for the simple reason that brands are no longer just a marketing issue.

Relationships Among Organizations, Products, People and Brands

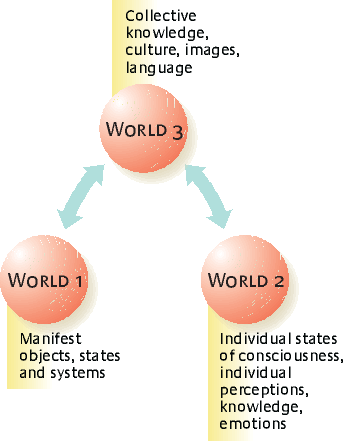

To understand the evolving marketplace, it is essential to capture the full dimensionality of the relationships among organizations, people, products and brands. Thethree-worlds hypothesis9 of philosopher of science Karl Popper10 — originally developed as a conceptual tool to explore the mind-body problem in philosophy — provides an excellent means of doing so. Popper’s World 1 is defined as the realm of physical objects, states and systems; World 2 is the realm of subjective experiences involving thoughts, emotions and perceptions; and World 3 is the world of “culture” rooted in objective knowledge, science, language, literature, and so on. (See “The Relationship of Products, Brands and Culture.”) In the context of brands, the three realms of relevance are: (World 1) manifest goods and services; (World 2) individual thoughts, emotions, needs, wants and perceptions; and (World 3) collective knowledge and images concerning brands.

Popper’s framework highlights the relationships among products, individuals and brands. It shows that the effect of a manifest product or service in World 1 (for example, an Apple computer with its familiar logo) on the collective knowledge of the brand in World 3 (the brand name Apple, Apple Computer, Inc.’s share price, its product specifications, its documented history etc.) is always mediated by, and thus a function of, intervening responses by individuals (World 2).

The framework also indicates that attempts to modify Worlds 1 and 3 — for example, by repositioning a brand — will always implicate the subjective worlds of the individuals managing and involved in the process, as well as the worlds of customers and other stakeholders in World 2. Further, it reveals that these changes can never entirely determine one individual’s World 2; that is, the meaning attributed to the brand by a specific customer.

This implies that brands are always part manifest (World 1) and part abstract (Worlds 2 and 3) and that the meanings that individuals attach to brands can range from the primarily functional (in the sense of what the branded offering can do in World 1) to the primarily enacted (what the branded offering can mean in World 3). The meanings associated with a brand in World 3 are always multiple and always equivocal because such meanings reflect individual differences in World 2. At the simplest level, what the brand means to the organization and its members may differ from what it means to its target customers or to other stakeholders, including the public at large. As such, an individual’s brand meaning and experience can never be entirely determined by the conscious intention or volition of others.

Dr. Martens shoes illustrate the three-worlds model as well as the fact that the same brand can have multiple meanings to different stakeholders. The ruggedly constructed, air-cushioned product (World 1, the physical) made by R. Griggs Ltd. became a brand (World 3, the abstract) with very different meanings to different stakeholders (World 2, the individuals). To management in the young British company in the early 1960s, the brand represented a sensible, durable shoe or boot, originally marketed to police and postal workers. But the brand took off when it was embraced by subculture groups, including punks and skinheads; to them, it represented a jarring, attention-grabbing fashion statement. And to the public at large, the brand soon came to embody a nonconformist symbol of rebellion against authority. Each constituency viewed the brand differently, and the brand shifted over time from a singular emphasis on the footwear’s physical qualities and performance to a complex image that blended manifest qualities with abstract cultural interpretations.

Refining Brand Equity: Key Dimensions

Popper’s three-worlds hypothesis highlights the fact that the role of a brand involves overlaps among all three worlds. Thus, brands can never be understood in and of themselves. They are not simply “created,” “owned” or “used” by management. Rather, they have a life and meaning beyond and, to some extent, independent of that intended by their initiators. For example, Apple’s Newton digital handheld device, abandoned by the company in the late 1990s, has attracted and still sustains a lively grass-roots brand community.11

These considerations complicate our current conceptualizations of brand equity. At the simplest level, brand equity assesses the value of a brand. Most managers understand the two current perspectives: the financial and behavioral views. The former, typically championed by consulting companies such as Inter-brand Corp., often result in press reports claiming, for example, that “Coke is the world’s most valuable brand, worth X billion dollars.” The behavioral view typically uses surveys to determine what a particular brand means to customers, how valuable it is to them and how the answers compare to those for other brands. These two perspectives are usually combined in a definition of brand equity as “customers’ willingness to pay a differential for one product over another when they are basically identical.”

The current preoccupation with brand equity is often traced back to the takeover of the British chocolate company Rowntree by Nestlé in the late 1980s.12 Many financial analysts and journalists began to see that part of the motivation for many company takeovers was the realization that the acquisition of brands was more profitable than spending years and vast sums of money to develop and nurture comparably successful brands. The shift in emphasis from physical assets to brands — from Popper’s World 1 to his World 3 — was under way.

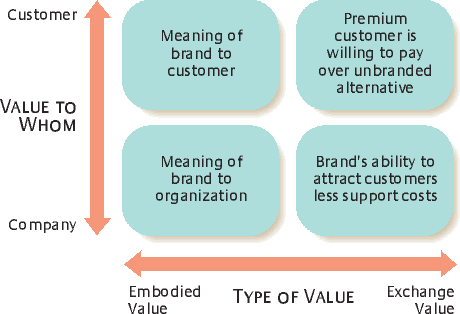

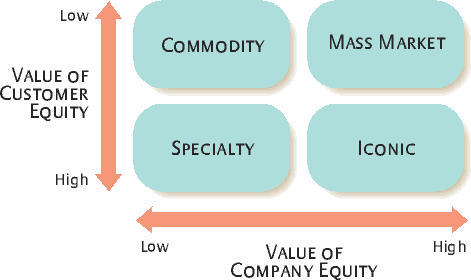

A more nuanced view of the value of a brand will distinguish between brand equity, which pertains to the perceptions of a brand, and value of the equity, which reflects the monetary value of the brand to the company. We term these two aspects embodied value and exchange value and combine them with a distinction between value to whom and type of value. (See “A More Nuanced View of Brand Equity.”)

The embodied value to the company describes the perceptions and values that the company’s managers see in the brand. Of course, even inside the company there is heterogeneity in these perceptions. Employees’ perspectives on the brand may vary by function and they’re unlikely to mesh with those of management, much less those of the marketing department. Yet the contradiction is this: Managers and employees alike are urged to manifest or “live the brand” as if it were one unified, shared concept.

The management perspective may also not coincide with those of external groups.

Customers will have their own take — witness the responses to KitKat’s exotic flavors and to Apple’s Newton. Other external audiences have their own sets of associations or embodied values: The expectations of suppliers, workers or consumer activists may differ significantly from those of brand-loyal customers, as McDonald’s Corp., now challenged to pay higher wages to tomato pickers, can attest. The expectations of legislators or regulators may well be influenced by such groups, as well as by the company that owns the brand in question.

At the same time, the “exchange” value of the brand equity in the product (or even in the company) depends on cash-flow streams resulting from the company’s ability to use a brand to acquire and retain customers — an outcome dependent not only on the premium paid by a consumer for a branded good or service above that for an unbranded version of the same product but also on the number of customers willing to pay a particular price and the number of units sold at that price (World 3).

For example, a bottle of fine French wine selling in the United States for $100 can be said to have high customer exchange value for those willing to buy at that price, whereas the company exchange value would be low because relatively few customers are willing to pay such a price. Conversely, a mass-market wine sold in high volumes at low cost, such as many of those produced by E.&J. Gallo Winery, has low embodied value and exchange value for customers and high company exchange value for the producer.

We can develop this distinction further by mapping customer equity against company equity. (See “A Typology of Exchange Values.”) Gallo wines would clearly fall in the top right-hand corner among the mass-market brands, along with many well-known names such as Tide, Lipton and Heinz. By contrast, Ferrari, Porsche, Perrier and Grolsch are solid bottom left-hand specialty performers. Meanwhile, many brands that have traditionally fallen in the top left-hand corner — with all the disadvantages that parity status entails — have worked hard to extricate themselves. Indeed, the revival of the Arm & Hammer brand of the privately owned chemical company Church & Dwight Co., Inc. demonstrates vividly that all is not lost even when your product is as unremarkable as baking soda. Until Arm & Hammer seized the day, who knew that baking soda — beyond its traditional service as tooth powder and antacid — could also be used as carpet deodorant, swimming-pool cleaner and kitty-litter freshener?

Of course, many companies seek the desirable bottom right-hand “iconic” position exemplified by Microsoft, Coca-Cola, Starbucks and Nike in recent years. There is the danger that as former specialty brands attempt to become iconic, or are deemed so by a significant number of stakeholders, their customer-embodied value deteriorates and they become mass-market brands. The once-coveted Halston and Pierre Cardin fashion brands have suffered such a fate, while Martha Stewart, Tommy Hilfiger and possibly even Tiffany appear to be headed in the same direction.13

Introducing the Brand Manifold

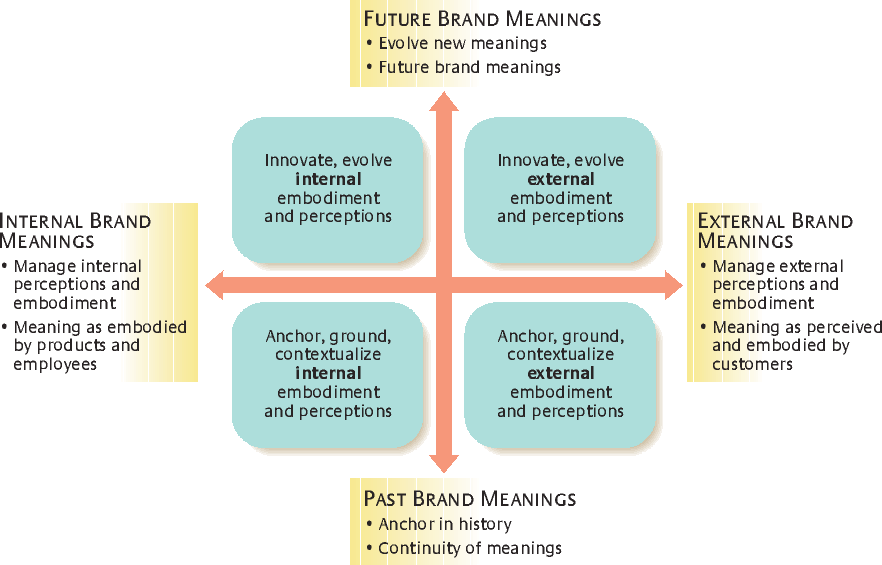

In mathematics and engineering, the termmanifold refers to a topological space or surface, and in physics it designates the space-time continuum. Similarly, the notion of a brand manifold suggests that brands have multiple dimensions: Their meaning varies over time and according to a multiplicity of constituencies. These two dimensions define a matrix of possibilities with which managers must interact.

Temporal Factors

Within a given cultural context, language and meaning are enmeshed in a continual process of evolution. The significance of a brand will change continually: Pontiac and Mercury mean something different to today’s car buyers than they did to buyers in the 1950s, now that those models share the roads with Nissans and Hyundais. The insight that brands are rooted in a broader context, taking their embodied meanings from discourses with their relevant stakeholders, carries important implications. Brand signification is never unilaterally created but always arises from dialogues in a wider linguistic and cultural community composed of various participants. As noted earlier, companies cannot so much manage a stable brand image as negotiate an evolving one. This emphasis on community, conversation and cultural change thereby assumes central importance in the management of brand meanings. Such meanings are temporal in two senses — the sense in which they change over time and the sense in which their creation is a process of longitudinal negotiation, with present meaning always rooted in the past and future meaning always rooted in the present. Thus, the stewardship of a brand focuses both on the brand’s relationship with its past and on evolving new meanings for the brand as it moves into its future.

To manage a brand’s evolution successfully requires that the brand not lose its roots in the past. Rather, management must find ways to reinterpret the past in terms of the future or, in a complementary manner, to interpret the future in terms of the past. In launching its new Maybach automobile, DaimlerChrysler AG has attempted a similar approach: A lavish publication lauds the history of Wilhelm Maybach, one of the original founders of Daimler Motors, and his creations, using both German and English on opposing pages, to strengthen the etiology of the long-dormant brand.

That “everything old is new again” sentiment is just as visible in BMW AG’s ad for its “grand touring tradition” from the 1980s. Jaguar Cars Ltd. went even further with the introduction and subsequent success of its XK models, using images of its famous 1960s E-Type model in the launch advertisements and incorporating many classic styling cues in the new car, right down to the shape of its grille. Yet Ford Motor Co. recently failed to capitalize on the retro appeal of the Thunderbird. Not only did the car’s overall design not evolve in exciting directions, but the performance of the overweight vehicle was mediocre at best. The point is that it is crucial to emphasize ways in which a brand’s present position draws on its past meanings.

Multiple Constituencies

The second dimension of the brand manifold recognizes a company’s multiconstituency nature. It expands upon the traditional distinction between company and customer to encompass a variety of external and internal stakeholders. Today, companies market almost as avidly to the investment community, to government regulators and legislators, to suppliers and to present and potential employees as they do to their intermediary and final customers.

In expanding the concept of customers to embrace external constituents and in thinking about the organization itself having internal constituents, we recognize the vastly more complicated task of managing brands in the 21st century. These various stakeholders have differing perceptions, values and expectations. Rather than mediating a dialogue between company and customer, the brands must be seen as pivotal in an expanded “multilogue.”

Putting the temporal and multiconstituency elements together, we can envision practical applications of the brand manifold. (See “Exploring the Brand Manifold.”) As an example of internal anchoring (lower left-hand corner), consider the case of an offering whose designers consciously draw on relevant brand-related meanings inherited from the past, as in the case of the much-celebrated and recently resurrected MINI by BMW. Where such meanings exemplify a more external anchoring (lower right), we find associations with the past that thrive primarily by virtue of the impression they make on customers, as in the case of Chrysler Corp.’s retro-designed PT Cruiser and Ford’s retro-styled Mustang. A more innovative form of internal evolution (upper left) would occur, for example, when a brand such as Porsche AG’s Cayenne sport utility vehicle offers advanced features that are perhaps best appreciated by the company’s engineers, its skilled workers or other automotive experts. If such features can be successfully communicated to customers, the company also achieves external evolution of the brand (upper right), as in the case of GM’s military-styled Hummer vehicles. In effect, the companies just mentioned have used brand-manifold principles in designing their products and bringing them to market.

Managing Manifold Worlds

So how best to manage with the brand manifold as much as any brand can be managed? It is not easy. With the disappearance of the distinction between products and brands, products have become symbols in themselves. The signifier — the physical product itself — has become the signified: A Bentley Continental car or a Coca-Cola drink or a Coach handbag is both a product and a symbol.

Indeed, brands themselves have become product offerings. At a store for aviation buffs in Carmel, California, one of the authors found authentic first- and business-class Pan Am travel bags on sale years after the airline’s demise. Apparently, the Pan Am brand has survived Pan Am World Airways.

The boundaries between producer and consumer have also blurred. In many cases, managers who might have thought of themselves as brand owners have become at best co-owners. In fact, their customers now own the brand in a very tangible and immediate sense. There is a powerful example in Harley-Davidson, Inc.’s14 brand, where Harley riders think of themselves as co-producers of the brand with a strong say in the design of future products, accessories and services. At another level, we find open-source software brands such as JBoss, Inc. and Linux OnLine, Inc.,15 where customers do actually co-produce both the brand and the product.

There will continue to be challenges as long as branding resides exclusively in the marketing department. At the departmental level, strategic vision tends to vanish in the “brand myopia” of day-to-day, short-term operational issues such as brand-extension decisions, customer research, packaging design and promotional tactics. Conversely, branding objectives drawn from World 3 can have major tactical and strategic implications for Worlds 1 & 2. A luxury image (World 3) may imply the use of platinum or silk (World 1) or may entail the creation of a prestige-oriented advertising theme (World 2). Think Cartier SA or Hermès International.

The implications for marketing managers are evident. We are certainly not the first to suggest that marketing executives need to consider the strategic implications of branding decisions, but it is news to many executives that customers and other constituencies will change the meaning of a brand over time irrespective of how it is perceived by the company. Thus, it is the responsibility of every marketing executive to determine how to manage the brand’s evolution. We believe that the brand manifold now gives them a sharper tool that can help them implement this advice.

At the same time, senior managers in other functions such as finance, human resources and operations must consider the impact of their actions on their organizations’ brands. The behavior of senior managers can have a significant impact on the brand perceptions of employees, customers, regulators, politicians and others. Managers’ failures to understand a brand’s embodied value can jeopardize shareholders’ interests and conceivably their own jobs, as our Daewoo/Chevrolet example illustrates. It is therefore incumbent on the chief executive officer, president and other top executives to acquire a deeper understanding of branding issues and to see the quintessential connections between those branding themes and the strategic trajectories of the organizations.

In our experience, top corporate managers have embraced the concept of brand equity. They also understand the desirability of repeat buyers and of customer loyalty. But if they think that equity and loyalty stem only from satisfaction (Popper’s World 2), they neglect the necessary provisions (World 1) that are essential to building a brand community based on trust and customer value (World 3).

The brand manifold framework reflects the energetic debate on the role of brands in the new millennium. It the fact that brands are very much alive and that they can rapidly, often in unpredictable ways. The framework also strates that brands are diverse, multidimensional — co-creations of the groups they are targeted to as much the producers themselves. Brands are embodied by products are enacted by customers and other participants in a process managers only partially control.

In short, a brand is protean and polyphonic, internal and ternal, past and future. Expressed through the instrument brand manifold, a brand plays a potential symphony of for managers who are willing to listen.

References

1. CAR, September 2005, 51.

2. D. Ball, “Flavor Experiment for KitKat Leaves Nestlé With a Bad Taste,” Wall Street Journal, Sunday, July 7, 2006, sec. A, p.1.

3. P. Berthon, M.B. Holbrook and J.M. Hulbert, “Understanding and Managing the Brand Space,” MIT Sloan Management Review 44, no. 2 (winter 2003): 49–54.

4. N. Klein, “No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies” (New York: Picador, 2000).

5. A. Chaudhuri and M.B. Holbrook, “The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loy alty,” Journal of Marketing 65, no. 2 (April 2001): 81–93.

6. F. E. Webster, Jr., “Understanding the Relationships Among Brands, Consumers, and Resellers,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28, no. 1 (winter 2000): 17–23.

7. “Death of the Brand Manager,” The Economist, April 9, 1994, 67–68

8. B. Morris, “The Brand’s the Thing,” Fortune 133, no. 4 (March 4, 1996): 28–38.

9. K.R. Popper, “Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach,” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979, rev. ed.); and K.R. Popper J.C. Eccles, “The Self and Its Brain” (New York: Springer International, 1979).

10. K.R. Popper, “Knowledge and the Body-Mind Problem: In Defence of Interaction,” ed. M.A. Notturmo, (London: Routledge, 1994).

11. A.M. Muniz, Jr., and H.J. Schau, “Religiosity in the Abandoned Newton Brand Community,” Journal of Consumer Research 31, no. 4 (2005): 737–747.

12. See for example, J.C. Ellert, D.G. Hyde and J.P. Killing, “Nestlé-Rowntree (A),” IMD Case 0111 (Lausanne, Switzerland: International Institute for Management Development, 2002).

13. T. Rozhon, “Men Ask: Who Needs to Buy Clothes,” New York Sunday, June 8, 2003, sec. 3, p.1.

14. J.W. Schouten and J.H. McAlexander, “Subcultures of Consumption: An Ethnography of the New Bikers,” Journal of Consumer Research no. 1 (1995): 43–62.

15. Y. Benkler, “Coase’s Penguin, or Linux and the Nature of the Firm,” The Yale Law Journal 112, no. 3 (2002):369–446.