How Increasing Value to Customers Improves Business Results

When Peter Leyland was appointed director of the European renal division of Baxter UK early in 1997, the business unit of the global health-care company was at a crossroads. The renal division was in the business of selling disposable bags used for kidney dialysis in the home. Although its market share for what is called peritoneal dialysis (PD) was close to 80%, PD was losing out to hemodialysis (HD), which removes toxic waste from blood. On a bag-for-bag basis, HD was cheaper. Meanwhile, new PD entrants were competing on price.

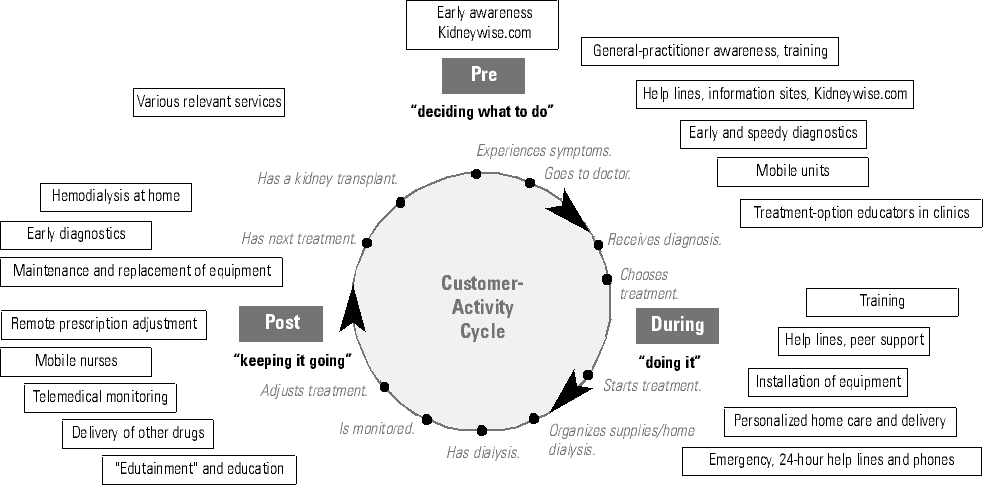

Leyland decided to cut the margin on the bags, but he would not cut costs for fear of negative customer reaction. He moved in the opposite direction, mapping with customers all the treatment activities — before, during and after the dialysis experience. Then he added value at each critical point in that cycle (helping patients, for example, to manage their private and professional lives around treatment, to update prescriptions, to dispose of used dialysis bags or to maintain machines).

Such attentions kept patients at home longer, greatly increasing the sales of dialysis bags. However, Leyland’s division was no longer thinking of itself as being in dialysis-bag manufacturing. It had started thinking like a dialysis patient caregiver. It had become a company with a customer focus. Most enterprises think they have a customer focus, but only those that have switched from traditional business thinking, which aims to extract value from products or services, really do. True customer focus means obtaining value for customers (whether or not they buy all the items they could of a company’s products and services) as well as obtaining value from customers (who voluntarily choose to stay with a company that obtains value for them).1

The problem with the conventional approach is that products and services — and the strategies designed to make and move as many such core items as possible at the maximum possible margins — are too easy for competitors to emulate and improve upon. Cost advantages appear only up to a point. And current research suggests that a customer loyalty focus based on the conventional approach leads to only short-term gains.2

Enterprises that understand and embody the vital components of customer focus can move ahead in a way that makes it difficult for others to catch up. A reinforcing mechanism enhances revenues while lowering costs, giving such companies the potential for sustained growth.

Revenues are enhanced not by selling more core items, but by increasing the amount of spending customers do with the company. Successful companies are maximizing customer spending at lower delivered cost by addressing:

- longevity of spending (perhaps even over a customer’s lifetime);

- depth of spending (greater share of wallet in specific areas of customers’ lives);

- breadth of spending (increased revenues from new sources of value, or value add-ons; for example, an airline might offer a value add-on of limousine rides to the airport); and

- diversity of spending (stretching into new areas of customers’ lives; for example, a company serving kidney patients might offer drugs for related diseases).

With customer focus, a company may end up selling fewer core items. Instead of trying to sell business customers more BP fuel to power their buildings, British Petroleum characterizes its offering as an opportunity to save on the energy bill. Rather than trying to convert companies from competitors’ products to their own, it obtains value for its customers by offering any form of energy that can save the customer money. BP expects to increase revenue and decrease costs by gaining longevity, depth, breadth and diversity of customer spending — not by obtaining increased revenue per product.

Enterprises that emphasize customer spending seek growth from customer activities. The Dutch global giant Unilever is an example of a corporation that saw its market value decline as a consequence of diminishing returns of growth through products. Unilever decided to reduce the number of its brands of home-cleaning and household products from 1,600 to 400. Today the company is capitalizing on the growing numbers of cash-rich but time-poor customers who may have been loyal to cleaning products in the past but who now want everything cleaned for them. So Unilever is becoming increasingly involved in cleaning activities. (See “Vital Components.”)3

Swinging the Power From the Company to the Customer

Enterprises that practice customer focus shift the power from providers to customers. The familiar example of Amazon.com is particularly apt. Amazon encourages customers to give feedback to fellow customers on books, CDs and services. Their experiences — good or bad — become totally transparent. Similarly, the power to be read is now in the hands of thousands of unknown writers looking for an audience: Through a special area of the Web site, they have potential access to 17 million Amazon customers in more than 160 countries. And Amazon assembles continually updated global sales listings for published authors, who are grateful to see how their books are doing in real time instead of waiting for a yearly report.

Once the basic principle of shifting the power to customers is accepted, Internet technology makes it more achievable. Sherry Coutu, founder and CEO of Interactive Investor International (iii), an online financial service started in the United Kingdom and globalizing rapidly, embedded in every step of growth the principle of delivering value at low cost.

The object was to get ordinary individuals to think of themselves as investors, rather than just savers, and to take control over their financial destinies. As Coutu puts it, “There was a disequilibrium in the market between those who knew things and those who didn’t, between those who were making the financial decisions and those who were on the receiving end of these decisions, between those who held financial power and those captive to this fact.”

In its five years of existence, iii has accumulated 1.2 million customers who visit its site regularly for increasingly longer periods — spending more per visit. They purchase the assets they want and self-assess performance as often as they like by monitoring their portfolios against all the major stock exchanges. They can talk to other online customers their own age with similar problems and aspirations — or to customers who have already bought stocks from suppliers they are considering. Professional financial advice is available from iii staff and partners by means of rapid e-mail recommendations. People who are moving about can link to iii through mobile wireless-application-protocol phones (WAPs), through personal digital assistants (PDAs) such as the Palm Pilot or through interactive television.

In another iii innovation, individuals’ requirements for loans and mortgages are auctioned on the Web to financial-services providers. The company makes relevant information, including credit ratings, available to suppliers online and then invites institutions to bid.

After iii successfully handled its own IPO issue online, other enterprises asked the company to do online IPO issues for them. The company now offers these issues to registered customers prior to official IPO listings. In the past, it was difficult, if not impossible, for people to gain early access to issues. The company also enables individual investors, not just institutions or venture capitalists, to access private equity stakes in start-ups. And because the cost of raising funds online is low, start-ups that go to iii get cheaper funding more quickly than they would from venture capitalists or merchant banks.

Achieving Customer Lock-On

Customer focus promises to provide something traditional strategies never could — increasing returns. The value an organization derives from products diminishes over time, but the value of customer lock-on can increase.

How does customer lock-on differ from product lock-in?4 With lock-in, the customer has no choice. There may be only one supplier with a monopoly for as long as its particular technology wave lasts. Or customers may have made an investment in one product and then find that the switching costs are too high. Customers may be disenchanted with a whole industry but captive because everyone in the industry operates the same way. They are locked in until an alternative comes along.

In contrast, customers who lock on select the enterprise as their sole, dominant or first choice because of ongoing, superior value at low delivered cost. So another vital component of customer focus is to get a critical mass of customers locked on. With lock-on, it is not the product that keeps competitors away, nor is it the technology; it is the customers.

Articulating New Market Spaces

Under the old diminishing-returns scenario, growth meant stealing market share from other companies. In contrast, the increasing-returns model benefits companies that concentrate on dominating activities that produce customer results in new market spaces.5

A market-share focus can hamper an enterprise’s ability to grow. Trapped in product categories and product-line growth strategies, companies run the risk of not seeing new opportunities. Consider Lego, the Danish toy company. In 1995 it had a worldwide construction-toy market share of 72%; in Europe its market share in that category was just over 90%. But children were spending more of their spare time with computers, video games and television than with traditional toys. So while Lego had been gaining market share, toys in general and construction toys in particular had been losing their share of children’s spare-time activities.

Another risk with market share is that it doesn’t reveal the real competitors. Today IBM’s competitors are more likely to be Andersen Consulting and the software houses than the other hardware suppliers. Or an IBM competitor might be a company such as Cisco, with its Internet-based global networking capability.

So another vital component of customer focus is the ability to articulate and define the market space or spaces that the enterprise wants to occupy and in which it intends to dominate customer activities and spending. (See “Guidelines for Defining Market Spaces.”)

Not until the market space has been articulated can the new enterprise know where, how and with whom it should work. Only when IBM defined its market space as “global networking capability” could the various strands of the organization be pulled together and new capabilities built so as to lock on customers.

Delivering an Integrated Customer Experience

Another vital component of customer focus is providing an integrated experience. Once the market space has been defined, the next step is to map the customer’s activities and then work backward to decide what value is needed in the customer experience, when, who should deliver it and how.

Defining the Value Add-Ons

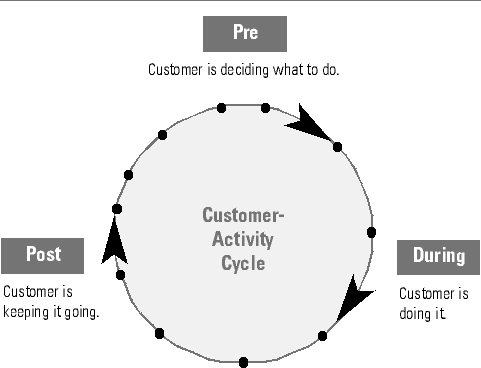

A market space is, in a sense, an aggregation of all the customer-activity cycles in a particular segment. (See “The Customer-Activity Cycle.”) In the travel industry, for example, the pre, during and post phases of a customer-activity cycle might include: first, deciding where to go and how, booking flights and getting to the airport; second, taking the trip, getting to and experiencing the destination; and finally, leaving the destination, finding transport, coming home and paying the bills. Customer-activity-cycle methodology can help managers assess opportunities for providing new kinds of value to customers at each critical experience.6

- Pre, or before: when customers are deciding what to do to get the desired result

- During: when customers are doing what they decided on

- Post, or after: when customers are maintaining the result — reviewing, renewing, extending, upgrading and updating

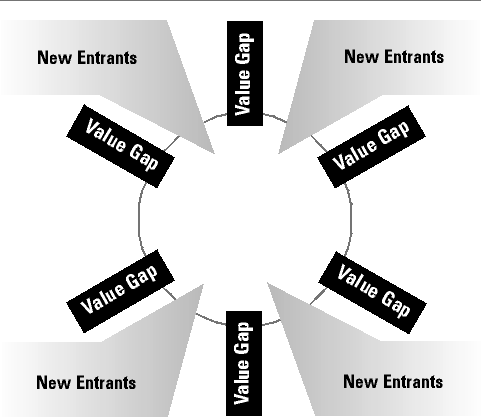

Any interruption in the flow of the customer-activity cycle creates value gaps, or discontinuities, that open access to competitors, unless the company fills the gaps first with value add-ons. (See “Capitalizing on Value Gaps.”) By filling value gaps, newcomers become killer entrants, establishing vital links to customers, building trust and opening opportunities for more business.

Filling the Value Gaps

In the late 1980s, IBM was still so fixated on PCs and mainframes that it allowed consultants, software houses, procurement specialists and third-party maintenance-service providers to leap into IBM’s value gaps and siphon off both customers and potential wealth from the global-networking-capability market space. Then Louis Gerstner and his team created a “New Blue,” aimed at providing value at critical points in the activity cycle. In the process, they made IBM the world’s largest provider of information-technology services. Today IBM earns more money from value-add-on services than from its hardware, software or middleware.

Enterprises that practice customer focus take advantage of value gaps. Amazon.com succeeded because there was a value gap in book selling. Customers wanted to find and purchase books without hassles — to get what they wanted when they wanted it, preferably from one source.

In air travel, Virgin Atlantic challenged the diminishing-returns, capacity-managing thinking of conventional airlines by merging travel and leisure into one integrated customer experience. The airline joined with limousine companies to develop a plan to take business-class passengers to many airports free of charge, check them in and issue an invitation to Virgin’s Clubhouse lounge. Today, at drive-in check-in areas specially designed for Virgin, a porter asks security questions, collects luggage and issues boarding passes. At the Clubhouse, passengers can shower, have a free manicure and pedicure, facial and haircut, or take a hydrotherapy bath. There are bars, virtual skiing devices, communications centers, libraries, music rooms with jukeboxes, rooftop conservatories and fine cuisine. Recent in-flight innovations include Jacuzzis, showers, ship-style sleeper cabins, live television and Internet-surfing possibilities. Because Virgin is a privately held company, it doesn’t share its financials, but the visible results of its approach include its ability to entice customers away from other airlines’ economy class and first class, as well as Virgin’s high valuation. The shares of other European airlines usually trade at a multiple of 0.8 of revenue. Virgin Atlantic is worth 1.2 times revenue.

Creating Breakthrough Value

As a matter of policy, Virgin goes beyond simply filling existing gaps — it consciously creates value gaps in the customer-activity cycle and then fills them with breakthrough value.

The aim is to redistribute value for business-class and first-class customers from the activity cycle’s pre stage (before take-off) and post stage (after landing) to the in-air experience. Virgin is reducing seat size for its upper-class travelers in a belief that they don’t need large seats at the pre and post stages but do want in-flight restaurants, lounges, and exercise and sleep areas at the during stage of the activity cycle. (See “A Customer-Activity-Cycle Exercise.)

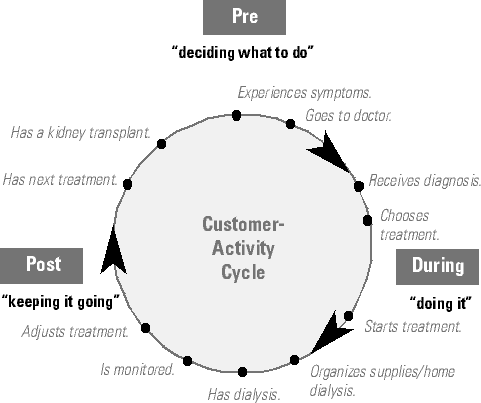

As another example, take a closer look at Baxter Renal UK. Leyland, the renal-business-unit director, collaborated with customers to map all the treatment activities — pre, during and post. Then he added value at each critical point in the cycle of activities.

Renal patients with serious kidney problems usually begin their treatment at home with peritoneal dialysis and then move on to hemodialysis, which requires four hours in the hospital three days a week — with additional, shorter stays for monitoring. Timing of the move to HD depends on how quickly the disease is diagnosed and treated.

The value add-ons Baxter introduced came in two waves. The first included all activities to obtain depth and length of spending by getting more people on PD earlier and longer; that was accomplished within 18 months. Loss of margin on the core items and the investments required to deliver value-added services were covered by selling more bags. The second wave involved getting more breadth and diversity of customer spending by moving into associated drugs (many renal patients suffer from additional diseases), competitive HD treatment (delivered at home) and transplantation research. From the customer’s viewpoint, all those areas were part of the same renal-sufficiency market space.

In the pre stage of the renal patient’s customer-activity cycle, the experience begins with symptoms, a doctor visit and choosing treatment. The during stage involves having surgery to gain access to the kidney, starting dialysis and managing the patient’s private and professional lives around treatment. Post activities include monitoring blood toxins, updating prescriptions, disposing of used dialysis bags, getting supplies, having machines maintained and replaced —and, inevitably, beginning HD and undergoing a kidney transplant. (See “How Baxter Renal Assesses the Customer-Activity Cycle of Patients.”)

Baxter’s value add-ons at the pre stage include raising patient awareness through its Web site, Kidneywise.com, speeding diagnosis and referral through mobile diagnostic centers and reaching out to general practitioners. (See “How Baxter Renal Uses the Customer-Activity Cycle by Adding Value at Each Point.”) In the United Kingdom, general practitioner outreach may take the form of working with the National Body of General Practitioners to raise the awareness of doctors who see few renal patients, inviting doctors to post-graduate nephrology seminars or educating doctors through Baxter’s Web site.

From research, the company discovered that patients choose hospital treatment rather than home treatment if they have not had enough time to think about how they will manage their changed lives. Baxter therefore put treatment-option educators in pre-dialysis clinics to take patients through the options and provide information on benefits to which they are entitled. Videos show alternative treatments, and Kidneywise.com offers support from other patients. The Web site also features “buddy groups,” from which Baxter collects information to augment its clinical knowledge. It looks for best practices and shares the learning with hospitals and doctors.

Value add-ons during the experience include training patients on treatment use and lifestyle modification. Patients can get help to set up equipment and can obtain emergency 24-hour clinical and technical help services by phone and Internet. Time spent on the dialysis machine has been turned into an educational activity, with machines linked to Kidneywise.com’s information, games, videos and patient discussions. The post stage includes home care, management of supplies and waste, and drug delivery for home or travel. Nurses regularly monitor progress. Home HD involves special telemedicine (distance-medicine) devices, equipped with software to capture information that is then disseminated over the Internet to those supervising care and to Baxter’s R&D team.

The move from selling core items to adding value to customer activities pre, during and post means enterprises can charge per customer outcome. So far, Baxter has benefited from the combined effects of longevity, breadth, depth and diversity of customer spending. Although unit profit margins had been down, by the end of 1999, sales and profits were up because patients were staying on PD longer. The number of customers lost to death, in-hospital HD or transplantation was reduced by 50% in three years. The higher number of patients on PD improved PD’s depth of customer spending. Breadth was higher, too, because the share of advanced products and services as a percentage of sales doubled. Associated drugs, home HD therapy and information on transplants —as well as Baxter’s research into xenotransplantation (transplanting parts from compatible mammals) —are all contributing to greater diversity of customer spending for Baxter Renal, which hopes to extend the life and well-being of patients and create 30-year customer relationships.

Personalizing the Value Add-Ons

Adding value for a mythical average customer will not achieve and sustain customer lock-on. True customer focus demands constantly improving value for individuals, not groups. Personalized value strengthens the bonding that enables a corporation to initiate precise customer offerings.

An enterprise can use knowledge management and electronic technology to develop an intimate, integrated, long-term view of customers. It can anticipate customer needs and work with outside players to meet those needs.

How does Baxter meet unique needs? The company uses Kidneywise.com and video cameras built into the dialysis equipment. Doctors can see how individual patients are responding and can adjust prescriptions. Technicians at a renal unit can see what patients are doing through visual links and thus be more helpful in discussing problems.

The New Economics and the Reuse of Abundant Resources

Another vital component of customer focus is being able to reduce costs and pass savings back to customers to reinforce lock-on.

Under the traditional customer-loyalty focus, companies tried to maximize volumes of core items to reduce the marginal costs per unit. With customer focus, companies do not concern themselves so much with repeat episodic transactions of core items; marginal cost figures less in the financial algorithm. Customer focus and the increasing use of information, knowledge and technology have moved companies to concentrate less on economies of scale and more on economies of skill, stretch, sweep and spread.

Economies of Skill

The skill most critical in getting superior value at low delivered cost is the use of information and knowledge, and many new offerings from companies are based on that skill. The marginal cost of using and reusing resources as abundant as knowledge and information is minimal, if not irrelevant.7 After the initial investment in getting to know the customer, the cost of updating that information is low.

Moreover, knowledge of an individual customer can be leveraged for other customers. At Andersen Consulting, for example, the expenditure of time, money and energy used to develop information about a client is never repeated, because the knowledge is immediately recorded in the firm’s Knowledge Xchange system, making it accessible to 65,000 consultants for reuse with other customers. As one executive put it, “All of Andersen Consulting’s accumulated experience and expertise can get to a client at a moment in time without any additional costs.” Thus, the system that helps a new Andersen consultant work with an old Andersen client also can release captured knowledge and information for new applications.

Using customer input (in effect, having customers work for free) is also part of what drives new economies of skill. Amazon’s customers provide book reviews, and many of the site’s most popular features are the result of customer suggestions. Baxter uses customers to give moral support to other renal patients. At Lego, many of the adult fans are programmers who use the software and adapt it by taking it apart, adding their own ideas and incorporating the ideas of others. If their knowledge is harnessed, it could be a giant source of R&D expertise for Lego.

Economies of Stretch

Once lock-on has been achieved, the enterprise can stretch its brand into other revenue-generating opportunities of customers’ lives with very low cost. Virgin epitomizes economies of stretch. As market research reveals, Virgin customers say, “If the right product comes along from Virgin, we will buy it.”8 The group now has hundreds of companies with combined revenues of billions of dollars. CEO Richard Branson’s approach differs from the conglomerate thinking of the past, which favored taking many different companies with different customers and throwing them into a portfolio. With economies of stretch, customers that have locked on in one market space are taken into new market spaces. The company has no acquisition cost and low marginal cost, because information, knowledge and relationships are already established.

Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon.com, followed a similar approach and made the controversial decision to continue basing investment choices on long-term objectives rather than short-term profitability or Wall Street’s reactions. His aim was to get a critical mass of customers locked on and therefore create a platform from which to stretch his brand into many areas of customers’ lives.

Economies of Sweep

Using the Web, the marginal costs of acquiring new customers, communicating and creating and delivering offerings can approach zero. But enterprises that use Internet technology only to leverage costs without centering on customer needs cannot expect to lock on customers or compete sustainably. Customer focus can help such companies achieve economies of sweep. Thanks to technology, increasing numbers of customers can lock on at low marginal cost to the company. Once those customers are installed, they can create revenue-generating opportunities.9 As opposed to economies of scale, which involve making and moving volumes of products or services and then selling them at ever decreasing margins, economies of sweep can generate increasing returns.

Internet technology also keeps expenses level, no matter how many customers want a service at a given time. So the more a company uses it to produce value for customers, the more that company can increase capacity at little or no extra cost.

The interactivity of the Internet enables companies to deliver ongoing personalized value while avoiding trade-offs that in the past left customers on the losing end. Gone are the tensions between giving customers personal attention and saving on expenses. Having customers stay online longer is only minutely more expensive, and the benefits to both the customer and the company may be enormous. The Scandinavian car-sales site Auto-By-Tel, for example, would never cut time spent serving the customer to save money. “Information is gathered,” says Karl Nord of the Scandinavian operation, “until a customer’s needs are assessed, a set of options can be generated, and the best choice can be made. At the point of contact, customers can stay online as long as necessary. In fact, Auto-By-Tel actively encourages this because not only do customers feel happier that way, but they also make better, more informed decisions. This saves the auto dealers time and money, potentially shaving costs even more.”

Economies of Spread

Traditional thinking held that investments in R&D, marketing and the like had to cover costs as quickly as possible before competition moved in. Managers did not plan on spreading returns over a long period, but expected to make their money up front, with diminishing returns inevitable in the long run.

But with customer focus, once companies achieve lock-on and gather the critical momentum, revenues grow and costs decline, creating economies of spread and the potential for revenue to arch upward rather than diminish.

Why does customer focus lead to economies of spread? First, its information- and knowledge-intensive offerings reduce marginal costs, so that initial investments are amortized over longer periods —and larger numbers of customers — than is the case with traditional customer-retention and customer-loyalty strategies. British Petroleum, for example, will more than offset the investment it makes in providing business-to-business customers with lower energy bills. Suppose BP offers a particular beverage company a one-year, $1.5 million fuel deal that results in a net present value for BP of between $36,000 and $126,000, given the start-up costs. A 10-year deal could boost that value to $8.6 million. And if the deal helps BP gain new expertise, the company will have that expertise available for other customers and markets. Thus BP could further amortize its initial investment. Those are economies of spread.

Second, up-front investment supports future momentum. Once Baxter Renal UK had made its investment to become the provider of renal care in the customer’s home (HD competitors focused on hospitals), it achieved new economies by spreading the expenses through later gains, including longer-term agreements with hospital buyers. (In the United Kingdom, hospitals contract for and pay for home care.) And a look at Amazon through a lens that combines its income and balance sheet suggests that, with the money it has spent on warehousing, it will have enough capacity to keep growing without continuing to reinvest.10

Third, the more Internet technology-intensive the offering, the easier to scale up without high costs or serious time delays. Penetrating a new market or country can take days rather than months or years, and the initial costs can be amortized speedily — as iii found when it went into Hong Kong and South Africa.

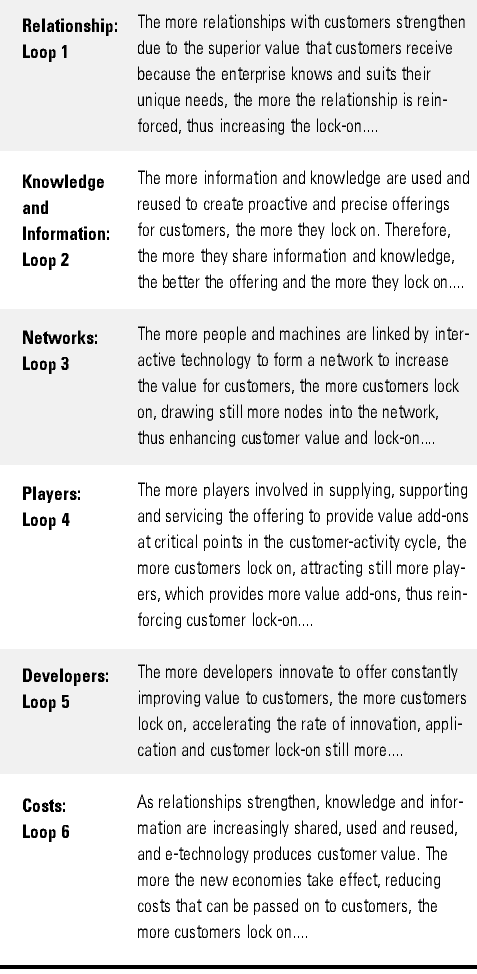

Building Reinforcing Loops Into One Cohesive Strategy

Customer-focused interactions loop back on themselves in six major areas: relationship building, knowledge-and-information acquisition, networking opportunities, increase in the numbers of players, increase in the numbers of developers and cost savings. The loop effect can create an advantage that continues to accumulate and multiply. Conventional strategies, based on unit transactions, involve continually counterbalancing demand and supply, with buyer and seller behavior discrete rather than regenerative.

Each of the six positive reinforcing loops has potential for producing its own increasing returns. When all six loops are combined into one cohesive strategy with the other vital components of customer focus, the potential is explosive. (See “Self-Reinforcing Loops Make a Competitive Strategy.”)

No matter which strategies companies used in the past (cost, differentiation, or customer loyalty and retention) to make and move more core items, diminishing returns were the inevitable outcome. Customer focus offers an alternative: infinite potential for increasing returns — and for getting and staying ahead in ways that make it difficult for competitors to catch up.

All enterprises, new or long-established, can benefit from customer focus. They don’t have to be big; they don’t have to invent or own anything. But they do have to leave behind transactional, linear thinking. With the vital components of customer focus clearly understood and firmly embedded in their strategies, they can achieve a longer, deeper, wider and more diverse share of customer spending. And they can lower their costs through economies of skill, stretch, sweep and spread. Moreover, they can increase the probability of long-lasting competitiveness — success breeding success — the ultimate aim of any sound strategy.

References

1. Paul Romer, “Increasing Returns and Long Run Growth,” Journal of Political Economy 94, no. 5 (October 1986): 1002–1037.

2. For more on the classic notions of customer loyalty and retention, see:

F. Reichheld, “The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits and Lasting Value” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

For a view on one-to-one marketing, see:

D. Peppers and M. Rogers, “The One-to-One Manager: Real World Lessons in Customer Relationship Management” (New York: Doubleday, 1999).

For research on the problems of short-term gains and diminishing returns from customer-retention strategy based on products, see:

J. Deighton and R. Blattberg, “Manage Customers by the Customer Equity Test,” Harvard Business Review 74 (July–August 1996): 137–144; and

N. Piercy, “Market-Led Strategic Change” (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000).

3. In his article “Marketing Myopia” (Harvard Business Review, September–October 1975), Ted Levitt asked managers, “What business are you in?” He pointed out that a railroad company, for example, is not in the railroad business but in the transportation business. Levitt provided the philosophic ground for thinking more about customers’ needs, but in the decades that followed managers translated his ideas into, “What other products should we be in? If not trains, then cars or trucks?”

4. For a managerial discussion of product-based lock-in, see:

A. Hax and D. Wilde III, “The Delta Model: Adaptive Management for a Changing World,” Sloan Management Review 40, no. 1 (winter 1999): 11–28; and

C. Shapiro and H. Varian, “Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999), chapter 6.

5. The notion of market spaces was first discussed by S. Vandermerwe in “The 11th Commandment: Transforming to ‘Own’ Customers” (London: John Wiley & Sons, 1996).

For related reading, see:

W. Chan Kim and R. Mauborgne, “Creating New Market Space,” Harvard Business Review 77, no. 1 (January–February 1999): 83–93.

6. The customer-activity cycle as a methodological tool for customer-transformation strategies was first published by:

S. Vandermerwe, “Jumping Into the Customer's Activity Cycle,” Columbia Journal of World Business 28, no. 2 (summer 1993): 46–65.

7. The inherent abundance of intangibles and the exponential implications are discussed in:

J.B. Quinn, “Intelligent Enterprise: A Knowledge and Service Based Paradigm for Industry” (New York: Free Press, 1992).

8. J. Ford, “The Future for Virgin: Will Branson’s Cash Keep Flowing If the Music Stops?” Financial Times, Aug. 13, 1998, 5.

9. For more on the Web and increasing returns, see:

J. Hagel III and A. Armstrong, “Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Communities” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997).

10. Conversations with Michael Mauboussin, Credit Suisse First Boston, 2000.