Managing Service Inventory to Improve Performance

In service businesses as in others, work can be performed and stored in anticipation of demand. By wisely choosing what kind of inventory to hold, companies can improve quality, response times, customization and pricing.

Topics

In recent years, the practice of pushing product by building inventory in anticipation of demand has fallen out of favor. Many companies have shifted to a“pull” environment, in which they build product only in response to actual demand. These firms have moved the “push-pull boundary” — the point at which a supply chain switches from building to forecast to reacting to demand — away from their end customers. By decreasing the amount of work completed before actual demand is known, firms avoid costly mismatches in supply and demand. For example, Dell Inc. has assumed and maintained a leadership position in the personal computer industry in no small part by setting its push-pull boundary to offer customers greater customization.

Given that repositioning the push-pull boundary has paid huge dividends for many product-based firms, it is only natural to wonder what kind of promise this approach holds for service firms. On the surface, the answer seems to be very little. A basic tenet of service management is that services cannot be inventoried; without inventory, the location of the push-pull boundary seems to have little relevance. Yet this view relies on an extremely narrow definition of inventory as finished product waiting for customers. In practice, inventory also serves as a way to store work; because the work has been stored, customers don’t have to wait for it to be performed. In a service setting, then, the placement of the push-pull boundary defines the portion of the work that has been performed and stored before the customer arrives. We call this work “service inventory.”

Service inventory includes all process steps that are completed prior to the customer’s arrival. As with physical inventories, service inventories allow firms to buffer their resources from the variability of demand and reap benefits from economies of scale while also providing customers with faster response times. Having service inventory also facilitates using the customer as a resource and offers the potential for automating the process. By using the correct form of service inventory, companies can offer better quality, faster response times and more competitive pricing. In this article, we will discuss how moving the push-pull boundary in service firms can be a strategic lever in designing and managing service offerings.(See “About the Research.”)

Services as Attributes and Processes

Service inventory needs to be viewed in the context of how firms compete and create value for customers. Every service represents a bundle of attributes — quality, speed, customization and price — produced through a set of processes. Customers elect to buy from a service provider only if the attributes of its offering are more attractive than the available alternatives.

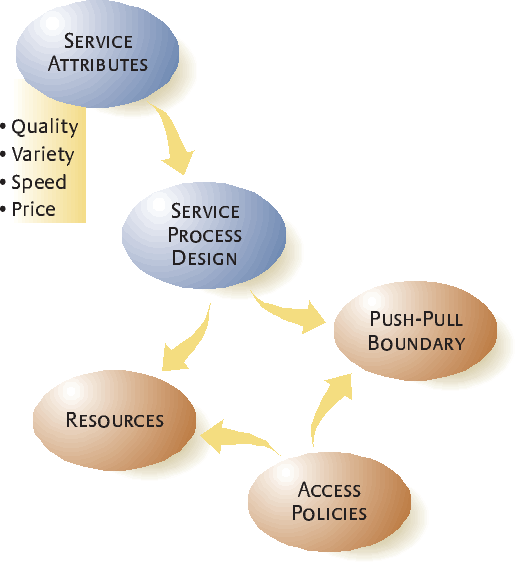

How well a service firm delivers its bundle of attributes depends on its process choices. Thus, process design is one of the most fundamental managerial decisions. We emphasize three drivers of performance: the placement of the push-pull boundary, the level and composition of resources and access policies. (See “A Framework for Service Process Design.”) The push-pull boundary determines how much work is done and stored as service inventory in anticipation of demand. Resources —that is, the people and the equipment that the provider employs — are used to perform the actual work of delivering a service. And access policies are used to govern how customers are able to make use of service inventory and resources (for example, when does an airline traveler complete check-in at a kiosk instead of going through an agent at the counter?). Most studies of service processes have focused on resources as the key lever in service design and performance. However, decisions about the push-pull boundary, resources and access policies are interrelated. A firm’s ability to deliver targeted levels of quality, speed, customization and cost for given resource levels depends on both how much work is done ahead of demand (and thus how much work must be done in reaction to demand) and how the firm allows customers to tap into its resources. Where to locate the push-pull boundary is thus a significant decision in service-process design.

The Role of Service Inventory

There are many different types of service inventory, and the choices a service provider makes depends on its industry and desired position in the market. A rheumatologist, for example, needs to produce letters for insurers on the status of patients. A system that automatically helps generate these letters represents a type of service inventory. The tools that help customers set up and run online auctions on eBay Inc. constitute another type of service inventory. Credit rating agencies, which sell consumer data and credit scores to financial institutions, have built their entire industry around service inventory. Financial institutions, in turn, have their own form of service inventory in the predetermined rules they apply to different customers on the basis of their financial profiles and credit scores. In all these examples, the service providers have shifted the push-pull boundary by performing some part of a service before the service request has arrived.

The title insurance industry illustrates some of the potential gains of moving the push-pull boundary closer to the customer. Title insurance assures a prospective property buyer (or, more specifically, a buyer’s lender) that a particular property title is unencumbered by liens or any inheritance claims. The title insurance industry has traditionally operated in a pull mode: Research about a property is initiated only when a customer requests a new policy. However, the Radian Group of Philadelphia has begun to alter this practice by gathering and storing the title information in anticipation of customer demand. Radian collects existing tax records, probate filings, deed registrations and other public records related to properties. Because it stores the records in its own database, Radian can offer title insurance on refinancings quickly and cheaply. It charges just $250 for a refinancing, several hundred dollars less than a conventional firm.1

Radian’s database of tax histories and deed recordings represents service inventory — indeed, it performs the same basic functions as conventional product inventory. The inventory acts as a buffer, allows the company to take advantage of economies of scale and expedites customer service. Traditional title insurance firms do little to buffer themselves from variability in the market. They must either carry excess resources to respond to demand spikes or impose long waits on customers, possibly resulting in lost sales. A traditional firm pulls tax records on only a handful of pending transactions at a time, but Radian can collect all the tax records at once — thus exploiting economies of scale for a much lower cost per unit. When a customer requests information, the turnaround time is rapid.

Radian’s service inventory is like product inventory in another important respect: There are real risks that it may go to waste. Many of the houses on which Radian collects information may not be sold or refinanced for years. Even when a property is sold, the buyers may seek title insurance from a competitor. Additionally, service inventory, like product inventory, limits what the firm can deliver quickly. If Radian does not have data from certain counties, it loses its advantage over other title insurance firms working in those markets.

As the title insurance example shows, service inventory is frequently made up of information such as databases or decision-support mechanisms. The availability of cheap computing and massive data storage often argues in favor of maintaining service inventory. In theory, Radian’s strategy of compiling information in advance of demand could be achieved without any computers, but this would require an army of clerks duplicating county records and a file cabinet for virtually every neighborhood. The costs of building and storing the inventory would outweigh its potential advantages.

Although service inventory is often based on information, not all information qualifies as service inventory. It must represent pre-performed steps in the delivery process that reduce the amount of work required when an order arrives. A database of consumer credit scores is service inventory for a mortgage lender, because evaluating credit history is a large part of the lending process. A database of everyone who has applied for a mortgage in the past year, however, does nothing to reduce the work required to reply to a service request; it is not service inventory. Similarly, code that allows house hunters to search real estate listings is service inventory, but generic software such as a word processing program is not. The house-hunting code includes logic to narrow search choices and display results prioritized by the client’s criteria; it therefore replaces a real estate agent’s time and effort. Word processing software and a personal computer simply replace a typewriter; the user must still compose the letter.

Service inventory based on information is in some ways distinct from product inventory. Creating a database is expensive, but thanks to the extreme economies of scale, the incremental cost of adding records to an established database is small. While the cost of producing 2,000 cars is much higher than the cost of producing 1,000 cars, the cost of building a database with 1 million records is not significantly higher than a database with 2 million records. Nor does service inventory get depleted the same way that product inventory does. A car dealer needs to have two vehicles to make two sales, but a service provider can allow hundreds or even thousands of users to tap into the same database simultaneously. Considerations in managing service inventory are thus different from those in managing product inventory. Much of supply chain management has focused on how much inventory to hold (that is, how many copies of one item); for service inventory the fundamental decisions turn on what kind of work to store. The service provider must determine for which of its offerings it should build inventory and at what stage of completion the services should be.

Our concept of service inventory is different from Theodore Levitt’s vision of industrialization of service.2 Levitt argued that a standardized service (such as Jiffy Lube International Inc.’s oil changes for vehicles) would result in significant reductions in cost. But such cost savings come at the expense of flexibility and variety (for example, Jiffy Lube does not service brakes). Moving the push-pull boundary toward the market can allow service providers to make decisions about which areas of improvement to emphasize: consistency, speed, customization or costs.

Service inventory is distinct from simple automation to reduce cost. Because it is often made up of information and algorithms, service inventory benefits from information technology. But successful implementation usually depends on human intervention. For example, while computer systems make it possible for Radian to collect its property tax records, people are needed to create customer value: Underwriters need to evaluate the information, address lender concerns and finalize the policies. Even when service inventory allows for a fully automated process, people will still be necessary to handle exceptions and adjust decision rules over time.3

The Strategic Impact of Pushing Services

Companies seeking to improve their competitive capabilities by using service inventory should pay attention to the four major service attributes: quality, speed, customization and price.

Quality

Consumers value various aspects of service quality, but in many cases transactional conformance — being able to get a well-defined service reliably and accurately — is the No. 1 concern. In this case, moving the push-pull boundary toward the market and increasing service inventory tends to increase service quality. An investor looking to rebalance his or her portfolio or sell stock, for example, places an extremely high value on transactional conformance. The investor wants reliable, accurate information about how best to make the adjustments, and service inventory provides an effective mechanism for satisfying this objective. Boston-based Fidelity Investments has reacted to this need by developing service inventory in the form of Web-based tools that allow investors to perform a variety of analyses.

Transactional conformance is also critical for purchasing airline tickets, making hotel reservations and seeking technical support. It is not surprising that firms have moved such transactions to centralized call centers and Web sites. A call center agent can work through a script to answer a customer’s question or can direct the customer to a Web-based “Frequently Asked Questions” page that presents the answer online. In either case, companies rely on service inventory to optimize the quality of the transaction and the experience.

Service inventory can also improve service recovery. Research has shown that customers encountering a service failure want the firm to assume responsibility for any shortcomings and guide them through a quick, hassle-free recovery process.4 Shifting the push-pull boundary and preparing for failures allows firms to respond smoothly and efficiently, assuming that they can anticipate the nature of the service failure. In air travel, for example, missed connections are inevitable. An airline could begin to rebook stranded customers once a delayed flight arrives. Alternatively, it could initiate the rebooking process before the flight even touches the ground. The latter approach, of course, requires building service inventory and may result in wasted effort if customers object to the proposed rerouting. However, if it’s handled well, passengers will be delighted.

Speed

Service inventory can shorten service turnaround time by reducing the amount of work required once customers enter the process. For example, a customer picking up laundered shirts and a suit from the dry cleaners frequently must wait for an employee to locate the items. Obviously, it would be faster for the customer if the cleaner consolidated orders in advance. This is what Zoots, a chain of dry cleaners based in Newton, Massachusetts, does. The company even takes the idea one step further; it puts the customer’s items in a secure locker (accessible 24 hours a day) and bills a preapproved credit card. Zoots has reduced the pull portion of the pickup process to a minimum. The customer spends less time in the store and is free to pick up dry cleaning at any time. No matter when customers show up, Zoots is able to achieve a higher level of staff utilization because employees are able to work at a steady rate.

Beyond trimming the amount of work done in the pull phase, moving the push-pull boundary can shorten waiting times by making it economical to use large amounts of inexpensive capacity. If the more difficult work is completed before a customer arrives, the required skill level for frontline workers can be reduced. Since lower-skilled labor generally costs less, firms thus can afford to deploy more capacity. The airline check-in process provides a good example. A common complaint about the traditional check-in process is not the time of the actual transaction —an experienced service representative can check in a passenger in a minute or two — but the time it takes to reach the counter. Because employees are expensive, check-in counters have usually been capacity constrained. Self-service check-in uses service inventory to address this problem. Today, the majority of domestic passengers check in using kiosks, which cost $5,000 to $10,000 each and are available 24/7. Since self-service check-in is inexpensive, airlines can justify providing more check-in capacity than ever before. Customers, meanwhile, benefit from less waiting.5

The goal of developing service inventory is not necessarily to simplify the service so that it can be delivered by less skilled resources. Its goal often is to save customers time by making front-line workers more productive and flexible. For example, in a financial service call center, one agent properly supported by service inventory can sell a variety of complex products and handle a range of transactions. By increasing resource flexibility, service inventory can allow customers to receive a full range of services without having to endure a series of frustrating handoffs.

Customization

Whereas inventory generally tends to constrain customer choice, well-designed service inventory can be used to offer greater variety and customization quickly, at relatively low cost. Service inventory enhances customization by allowing general capacity to deliver specific results or by giving customers increased information and control. JW Marriott Hotels and Resorts’“At Your Service” program is an example of the former. The program keeps track of individual guest preferences and complaints. If a guest prefers feather to foam pillows, it is noted in the database, and the feather pillow will be on the bed the next time that guest checks into a Marriott hotel.6 Through this program, Marriott is building up its service inventory and using the inventory to customize its offerings. Marriott can take what would otherwise be a generic hotel room and tailor it to the traveler’s individual taste.

In contrast to manufacturers who need to weigh the economics of increasing their inventory’s amount and variety, many service providers are finding that they can shift the push-pull boundary closer to the customer at very little cost. There are three key reasons why service providers are in a better position than manufacturers to offer variety by building service inventory. First, as noted, service inventory is cheap to hold and maintain. Marriott can afford to track its guests’ idiosyncrasies because the cost of storing and accessing data is minimal. This is in stark contrast to manufactured products, such as personal computers, for which the cost of holding all possible configurations in inventory is prohibitive. Second, the uniqueness of a service often comes from the information individuals enter themselves, not from any special processing. For example, the specific makeup of someone’s investment portfolio is unique, but the processing required to analyze the portfolio is standard. Well-built analytical tools permit each investor to perform an analysis that is tailored to his or her own situation. The same is true for online auctions through eBay. Although every auction is unique in terms of the merchandise and bidders, they can all be set up and run using the same generic tools. Finally, service inventory built on information is inherently modular. This enables service providers to use a limited number of parts to produce a wide variety of outputs, depending on a specific user’s preference. For a Web portal such as Yahoo Inc.’s My Yahoo, for example, the service inventory is composed of databases that hold the articles and the queries used to create customers’ customized Web pages.

Firms can use service inventory to increase customization by giving customers more information and control. Precor Inc., a manufacturer of high-end fitness equipment based in Woodinville, Washington, does this by giving customers a tool to evaluate how its equipment will work in their home. Precor’s products represent a significant purchase for most consumers, so the sales process involves considerable consultation. To facilitate the process, Precor’s Web site includes a feature called “Space Planner.” Customers can specify the room under consideration (such as a bedroom), its dimensions, fixed features (such as closets) and other restrictions (such as beds), and the tool offers suggestions for locating the equipment. By giving customers greater control via service inventory, Precor offers a highly customized service. Other companies use service inventory to make customization opportunities available. Airline kiosks present passengers with a map of the available seats on their flight and allow them to choose the one they prefer. According to Kinetics, a maker of self-service kiosks based in Lake Mary, Florida, and a subsidiary of NCR Corp. of Dayton, Ohio, improving service from the customer’s perspective is essential to implementing a self-service program successfully.7

Price

Moving the push-pull boundary in the direction of end users can offer significant cost savings, giving service providers greater pricing flexibility. The savings can flow from simply using less expensive resources and developing self-service options. Alternatively, service inventory can enhance the productivity and flexibility of frontline workers. Operating a technical support help desk, for example, is less costly if user problems are handled quickly and correctly the first time.

Service inventory also lowers costs by fulfilling the basic roles of inventory: exploiting economies of scale and buffering resources. For example, Radian is able to undercut a traditional title insurance firm’s price in part because it collects information in batches, which greatly reduces its marginal cost of evaluating a property. Marriott’s “At Your Service” program lowers the company’s cost by allowing for higher staff utilization. By anticipating guests’ needs, the hotels are able to customize rooms early in the day, instead of having to respond to everyone’s requests at the end of the business day. (See “How Service Inventory Improves Performance Along Service Attributes.”)

Locating the Push-Pull Boundary Strategically

Although many companies are already using service inventory to carve out unique positions in their markets, we believe significant opportunities await firms that are willing to rethink the location of their push-pull boundaries. For example, industry experts estimate that only 10% of telecommunications industry service orders are done through the Web (compared with about 30% of airline ticketing). Since the cost of processing a transaction through a traditional call center is about 10 times that of processing the same transaction over the Internet, there is clearly a payoff in moving more customers to cheaper resources.8

This is not to say that all service inventory is worth building. Before investing in service inventory, a service provider must consider when service inventory will enhance its competitive position and how its access policies can be adjusted to maximize the chances of success.

Determining the Right Level of Service Inventory

The ideal location of the push-pull boundary depends on the specific characteristics of the particular market and the cost of creating service inventory. The market characteristics determine the likelihood that service inventory will actually be used; the cost influences how risky it is to build service inventory. As with product inventory, building service inventory is more attractive when there is a greater chance that it will actually be used or when the cost of building it is low.

One market characteristic favoring high levels of service inventory is when customized service can be delivered through the application of a common process. Automated teller machines at banks, self-service check-in at airports and eBay auctions are good examples; the process is standardized, but the transaction details differ. In each case, a standardized process allows for the building of service inventory. This, in turn, facilitates self-service by the customer, quickly and at low cost. By concentrating on what is common across the various service requests, the firms can build service inventories with the knowledge that they will, in fact, be used.

Another market factor favoring service inventory is the presence of frequent users who value customization. Marriott maintains significant service inventory in the form of information on repeat customers, and it uses the customer data to adapt from one guest to the next. Because the service inventory revolves around regular customers, it is likely be used over and over. High levels of service inventory are also justified if it is cheap to maintain, store and augment. Thus, firms such as Web portals can build high levels of service inventory because the marginal cost of adding and storing records is small. Further, a greater breadth of coverage increases the value of the service to customers.

The level of service inventory can be increased if its modularity supports wide product variety and allows one process to deliver highly customized results. Modularity allows each additional item in service inventory to increase the variety of offerings exponentially. (See “Moving the Push-Pull Boundary.”)

Controlling Access to Increase the Value of Service Inventory

Once a firm has created service inventory, it is important to encourage as many customers as possible to use it. For example, having a check-in kiosk provides little value to an airline if most passengers continue to wait in line for customer service representatives. Some firms have responded to this challenge by forcing customers to access service inventory before placing demands on more expensive resources. For example, American Airlines usually allows domestic passengers to access its counter personnel only after they have used a self-service check-in terminal. In other settings, firms have built-in profiles for identifying complex transactions that cannot be handled using service inventory. For example, lenders might develop automated rules to create three groups of loan requests — accept, reject and further processing. Only the requests that require further processing find their way to a person.

One way to direct customers to service inventory and away from expensive resources is to impose different costs. The difference may simply be a higher price; for example, most airlines now levy surcharges on tickets bought through a call center rather than over the Web. Alternatively, the higher cost may be levied in the form of reduced convenience. Most airlines have enough capacity that there is rarely any wait to check in at a kiosk, but there is almost always a line for an agent.

When the goal of service inventory is to increase customization or to provide additional services, access policies can be designed to reward the most valuable customers and to encourage retention. For example, Marriott’s “At Your Service” program is available only to frequent guests. Similarly, Fidelity makes its portfolio analysis tools available at no charge only to customers with significant account balances; other customers must pay to use the tools. In these examples, service inventory serves to increase the customer’s perceived value of the service. Regulating access allows companies to make sure that only certain designated customers receive these benefits.

Focusing on the push-pull boundary provides a distinct and novel way to think about service management. In evaluating where to set the boundary, service providers should think of service inventory as providing structure and support to the service encounter. The relevant questions for companies are: What do customers value? Do they want a simple, fast process, or do they want a single point of contact that can deliver a range of services? The former favors using service inventory to offer speed through ample, cheap capacity; the latter favors using service inventory to enhance the productivity of skilled resources. A focus on the push-pull boundary can help guide firms in designing their service processes. They can identify which process steps to complete in advance in order to move the push-pull boundary closer to the market and to elevate performance to higher levels.

References

1. Traditional title insurers have mounted legal challenges to Radian’s entry in the market. L. Gomes, “It Will Still Take Time, But Net Is Modernizing Home Buying, Selling,” Wall Street Journal, Dec. 6, 2004, sec. B.

2. T. Levitt, “The Industrialization of Service,” Harvard Business Review 5 (September–October 1976): 63–74.

3. T.H. Davenport and J.G. Harris, “Automated Decision Making Comes of Age,” MIT Sloan Management Review 46, no. 4 (summer 2005): 83–89.

4. S.S. Tax and S.W. Brown, “Recovering and Learning From Service Failure,” Sloan Management Review, 40, no. 1 (fall 1998): 75–88.

5. C. Fishman, “The Toll of a New Machine,” Fast Company 82 (May 2004): 91.

6. C. Harler, “CRM at Your Service,” Hospitality Technology (June 2002): 27–29.

7. Fishman, “Toll,” 91.

8. S. Andreu, E. Benni, W. Pietraszek and H. Sarrazin, “Automated Self-Service Comes to Telcos,” February 2005, www.mckinseyquarterly.com

Comment (1)

Pam Lassila