Prepare Your Company for Global Pricing

“Give me a global-pricing contract, and I’ll consolidate my worldwide purchases with you.” Increasingly, global customers are demanding such contracts from suppliers. For example, in 1998, General Motor’s Powertrain Group told suppliers of components used in GM’s engines, transmissions and subassemblies to charge GM the same for parts from one region as they did for parts from another region.1

As globalization increases, customers will rachet up pressure on suppliers to accept global-pricing contracts (GPCs). Purchasers may promise international markets, guaranteed production volumes and improved economies of scale and scope. But what if they fail to deliver or if suppliers’ global-price transparency inspires them to make unrealistic demands?2

Suppliers must make three key decisions: whether to pursue a GPC, how to negotiate the best terms and how to keep a global relationship on track. We have found that the best tool for suppliers is solid information on customers. Information can help the supplier make a sensible counterproposal to demands for the highest levels of service at the lowest price.

Ignorance is dangerous. Consider an advertising agency we’ll call Proscenium XL. In 1996, Proscenium XL agreed to a global contract to manage worldwide advertising for a U.S. Fortune 100 company. Having no significant business with the client in non–U.S. markets, Proscenium XL saw an opportunity to expand its relationship. However, the contract stipulated that Proscenium XL would charge lower fees in anticipation of higher volumes and would not represent any of the client’s non–U.S. competitors.

Upon inking the contract, Proscenium XL discovered new information. The client’s managers in non–U.S. markets had considerable autonomy. They demanded localized programs and services — and resented having to displace their old agencies. When many of the client’s managers abroad stopped using Proscenium XL, the agency’s U.S.–based global-account-management team was powerless, fearing to jeopardize U.S. business with the client. Soon the client dropped all non–U.S. business with Proscenium XL, which then was in a worse position in markets where it had sacrificed existing relationships with the client’s competitors.

Managers can learn much from other companies’ GPC experiences. We saw a need to extend current globalization research and study how suppliers approach global-pricing contracts. (See “Research Methodology and Data Collection.”)

Should Suppliers Accept Global-Pricing Contracts?

For suppliers to understand when they could benefit from a GPC, they should first consider why customers want them and then what they — the suppliers —might gain.

Why Customers Want GPCs

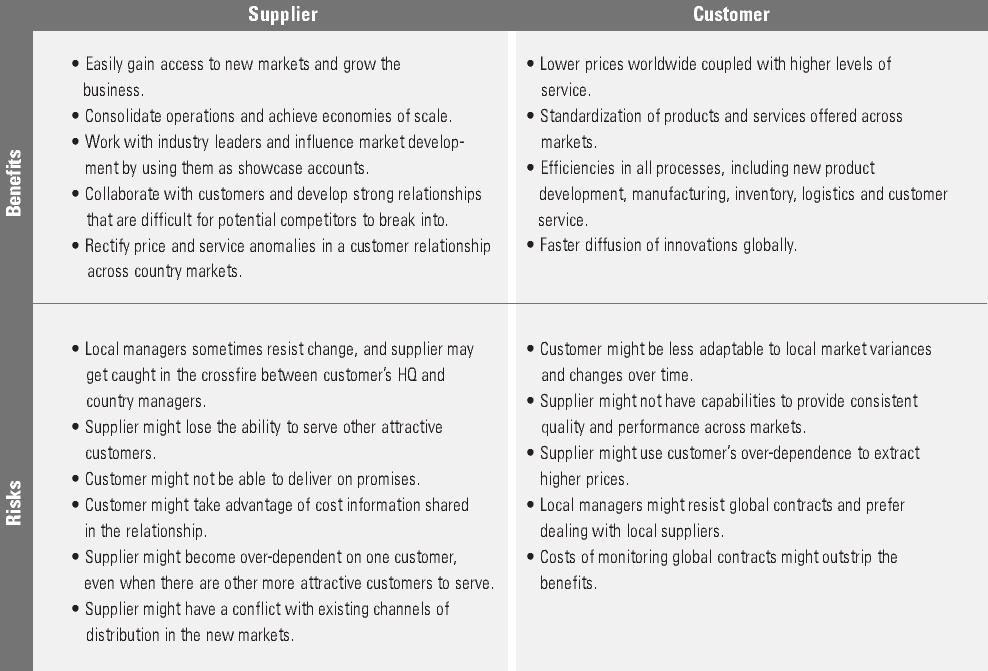

Customers’ recognition of procurement as a value-adding activity has sparked their interest in GPCs. Global customers now have the information technology and standardization of product lines to track suppliers’ product and service prices worldwide, consolidate demand and purchase centrally. Multinational corporations’ country subsidiaries continue to reduce autonomous contracting for supplies. So far customers enjoy most of the benefits, but some GPCs help suppliers, too. (See “Global-Pricing Contracts: Suppliers and Customers Have Different Benefits and Risks.”)

For the customer, a GPC improves operations efficiencies — for example, in product development, inbound logistics and marketing. A GPC helped one manufacturer (building the same motor to different design specifications, with different parts from suppliers in different locations) get a central design team, a standardized design and a single global supplier.

What Do Suppliers Gain?

Suppliers do not need to lose out when customers globalize. The most attractive global-pricing opportunities are those that involve suppliers and customers working together to identify and eliminate inefficiencies that harm both.

Sometimes suppliers do not have a choice. They don’t want to shut themselves out of business with their largest and fastest-growing customers. Supplier Procter & Gamble finds that 39 customers with international sales distribution account for 47% of total sales to P&G’s top 100 customers — and are growing 3% faster than the other 61.

For smaller suppliers and those lacking global reach, GPCs can provide international legitimacy and access to global markets. Multiyear GPCs can give suppliers a predictable flow of business, eliminate competition and tighten customer relationships. Suppliers with guaranteed volumes do not have to worry as much about beating the bushes for customers.

Also, global customers can become showcase accounts, bathing suppliers in a halo effect. One chemicals manufacturer concentrated on relationships with a few select customers. It had decided that its strength lay in value-added services but that potential customers in emerging markets were fixated on price. The select customers, however, were interested in money-saving supply and inventory-management initiatives developed jointly with the supplier.

Once the systems were established and providing benefits, competitors of the chemicals supplier’s showcase customers had to develop equivalent systems. Their first choice for a supplier was obvious.

Negotiating a Global Contract

If suppliers think a GPC will have a negative impact, they should negotiate better terms. The supplier should never customize to the point that it cannot transfer the learning and economies of scale. (See “Before You Sign: A Checklist for Suppliers.”)

The successful chemicals supplier customized only logistics and inventory-management systems, whereas Proscenium XL, the advertising agency, was forced to customize the basic product and incurred added costs. The chemicals supplier’s cost savings let it reduce the prices it charged the customer, creating a win-win situation. Proscenium XL found a whole new meaning for win-win: The customer won twice at the supplier’s expense.

A supplier’s size and account concentration can determine if a GPC is worthwhile. Committing to a global supply contract may increase risks for suppliers that are smaller than their global customers. One medium-sized Brazilian chemicals manufacturer committed 80% of production to a pharmaceutical company and nearly collapsed when the customer integrated production into its own operations.

Without a clear plan for how to serve global customers, suppliers can end up forging market-entry strategies on a case-by-case basis, as U.S.–based Entex Information Services Inc., discovered. That company’s entry into new countries is dictated primarily by the support requirements of its global customers.3

Global customers’ demands for detailed cost information also can put suppliers at risk. Toyota, Honda, Xerox and others make suppliers open their books for inspection. Their stated objectives: to help suppliers identify ways to improve processes and quality while reducing costs — and to build trust. But in an economic downturn, the global customer might seek price concessions and supplementary services. Throughout the 1990s, Japanese automotive companies pushed suppliers to accept lower margins. Since Asia’s economic downturn, large Asia-based electronics and personal-computer customers have postponed or delayed purchasing from smaller U.S. suppliers and have demanded price reductions.

And a global customer’s sudden growth can hurt the supplier who fails to think long term. Bausch & Lomb was supplier to Sunglass Hut, but the U.S.–based B&L account manager who negotiated the contract failed to anticipate the customer’s subsequent overseas expansion; he arranged a quantity discount schedule that was not anchored to the U.S. market. When Sunglass Hut expanded globally, the order quantities it placed with B&L soared; B&L had to supply large volumes of lenses globally at lower prices and margins than would have been the case with country- or region-specific pricing contracts.

The supplier has many questions to research. Will its products and services represent such a high percentage of the customer’s cost in a country that constant cost-reduction requests are likely? Will the supplier’s standardization spur customers to compare the supplier’s prices across markets, divert products across countries (creating gray markets) and resolve anomalies that might have given the supplier higher profitability?

Suppliers must gather information on competitors in local markets (specific geographic markets). Full-line suppliers may be able to offer lower prices through distribution economies of scale but then find that specialty players offer both cost savings and superior cross-border logistics management. Detailed information means informed decisions and better terms.

To design an effective global-pricing strategy, suppliers also must determine whether numerous single-country customers might be easier to deal with and more profitable than a large global customer. Suppose a supplier has been using local distributors to access and support local customers. A new global contract would mean having to sell directly to one enterprise while supporting others through independent channels. Suppliers must determine whether the global contract brings enough extra volume in a particular market — and an insignificant enough price spread — to warrant acceptance.

Will the global customer deliver on its promises? If the customer’s local operating units have profit-and-loss responsibility and see no price advantage in using a global supplier, they won’t. Only if local compliance is essential to a customer’s global strategy (for example, to ensure product integrity) or has a significant economic benefit can a supplier expect to be able to enforce a global contract.

Homework on Global Contracts

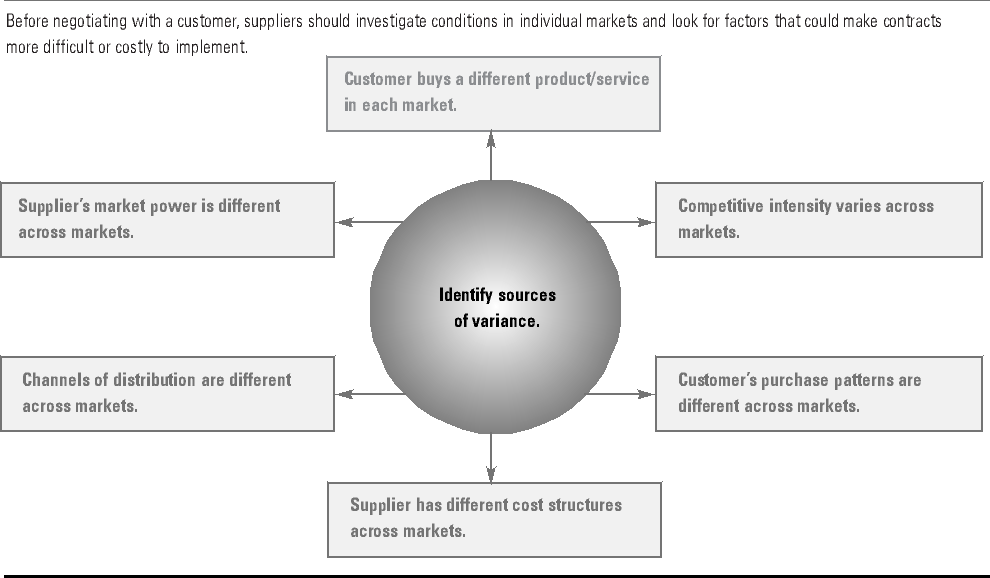

To extract prices that are commensurate with service levels, suppliers need a thorough knowledge of how customers vary in their product and service requirements across various country markets. They also need good information on their own company’s experience in different markets — the competitive intensity, distribution costs and price levels. (See “Suppliers Need To Do Research Before Signing Global-Pricing Contracts.”)

A product sold in different markets might vary as to formula, packaging or size, depending on local tradition, regulations or customer preferences. A supplier who forwards freight cannot offer the same price everywhere. The procedures involved in clearing products through customs and the costs of setting up warehouses vary. A supplier needs detailed, activity-based cost information before discussing global pricing.

All variations that affect the cost of serving a global customer (expedited delivery, backup inventory, technical assistance, after-sale service) should be reflected in a supplier’s price. One freight forwarder had useful information — a customer’s headquarters wanted faster cycle times, but its country managers cared most about lower handling costs; the firm was able to define the scope of services for each country and spread the price across markets.

Suppliers should research all variances: how global customers’ local managers differ as to typical size, frequency and predictability of orders; or whether a country offers only one distributor, which can charge whatever it wants.

Information is also needed on sourcing (whether the government mandates local sourcing of raw materials, transportation, processing and labor), different production costs in plants of varying sizes, and exchange-rate fluctuations. Because contractual terms can be difficult to change, anticipating ways to handle variances is important.

A supplier’s ability to extract different prices is also affected by competitive intensity in local markets. If one of a supplier’s subsidiaries controls a particular country’s supply, it can charge a higher price there. But if a supplier has broken into a new market using a low-price strategy to compete with an incumbent, it will have difficulty securing higher prices from a global customer in that market.

To prepare for a GPC, a supplier also must have detailed information about its own costs and prices worldwide. GPCs invariably reveal anomalies. Suppliers must try to resolve matters such as the same customer paying different prices for the same product in different countries. Otherwise, suppliers could be blindsided by a customer or competitor with greater knowledge of their prices than they themselves possess.

That is happening to suppliers of telecommunications infrastructure. Their fastest-growing customers —regional and global telecom operators — are uncovering price discrepancies. Customers that find significant variations righteously demand that suppliers lower prices (but without compromising service).

However, customers truly committed to the global marketplace realize that suppliers have legitimate cost variances that necessarily result in pricing differences. They hesitate to push too hard for the lowest price for fear of reduced service quality or suppliers’ unwillingness to help out in times of need. The more powerful a supplier, the less likely it is to offer the lowest price — especially if it expects a chain reaction among its other customers.

Ironically, the customer pressing for uniform prices is often itself pricing differently in different markets. It should be made to acknowledge this fact (another information-gathering task for the supplier). Suppliers need all the leverage they can get — especially if the customer commands a large percentage of the supplier’s profits.

How Suppliers Should Respond When Asked to Bid

When invited to bid on a global contract, a supplier may: decline to bid, submit a bid but hope to lose, bid for the business using the customer’s current terms, or bid only after modifying the terms.

Declining to Bid.

Declining to bid is feasible only if the global customer is peripheral to the supplier’s current sales (and the loss of business can be made up) or if the customer is not critical to the supplier’s future strategy. The option is viable for suppliers with diverse, fragmented customer bases that show no signs of consolidation and for suppliers that favor other global customers for strategic reasons.

Bidding to Lose.

Bidding to lose is an option for a supplier that already has good customers at the global customer’s country level. If the supplier is sure it can sustain the higher prices it gets from those customers, it might bid to lose is by demanding exclusivity. Most customers won’t accept that, fearing the supplier will leverage its monopoly later to raise prices.

Accepting the Terms.

A small or midsize supplier with international ambitions might accept a global customer’s terms. If the supplier is recently internationalized and lacks the solid local support organizations it needs, it might welcome the short-term convenience of a global contract. Or the supplier might accept the terms because it is highly dependent on the customer and cannot afford to lose the business.

Modifying the Terms.

In negotiating or bidding on the contract, the supplier might want to modify terms that define, for example, who makes decisions, what products and services are covered, the geographic scope, and the mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding price concessions. It might insist that the customer’s decision-making unit include line managers not just in procurement — especially those who like the supplier’s products and services and are not principally focused on price.

One of the most important areas for negotiation is service. The supplier should try to move the procurement discussion from product volumes and prices to cost-to serve (what it costs the supplier to serve the customer at the levels of quality, availability, warranty coverage and speed-of-repair service the customer wants).

A regional contract could be a test. If the supplier’s market share, positioning and pricing are more similar within a region than globally, a regional contract might be less disruptive. Or a supplier might offer a progressive year-end rebate based on the customer’s purchases (or on its increase over the previous year). A rebate concept can test the customer’s commitment and its ability to deliver. Even in industries that have well-documented adversarial buyer-seller relationships, suppliers can find the right GPC customer.4 In 1990, ABB found one in Ford, which cooperated on a deferred-fixed-price contract.5

Keeping the Relationship on Track

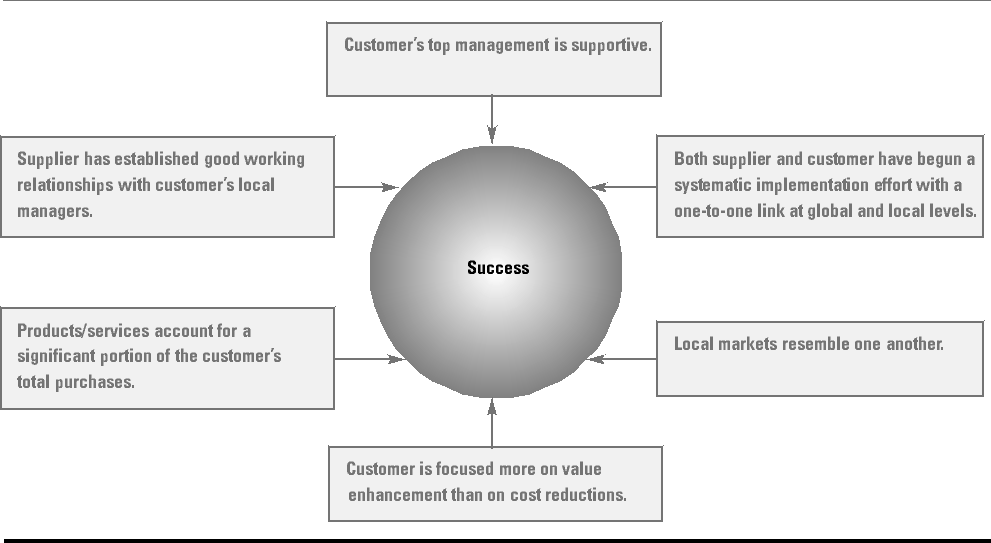

Thus, to ensure that a GPC will work for them, suppliers should gather information about the customer, the markets and the supplier’s own practices worldwide. Additionally, our research suggests that six factors are critical. (See “Factors That Affect the Success of a Global-Pricing Contract.”)

First, a customer’s senior managers must communicate total commitment — a prerequisite for overriding pockets of resistance from country subsidiaries.

Second, a customer’s corporate purchasing staff must not be the sole GPC implementers. The supplier’s local offices and the customer’s local managers must establish a good working relationship prior to the global contract, or it will buckle under resistance from purchasers who favor past suppliers.

Third, a systematic implementation process is needed for dealing with the idiosyncrasies of individual markets. Both suppliers and customers must contribute respected, empowered people to the implementation team — people able to analyze and assimilate cost-to-serve and price variances across markets and to get acceptance from stakeholders.

Fourth, the ease with which the two sides can work through the process is a function of the degree of homogeneity across the customer’s local markets. Markets that “march to a different drummer” are sometimes handled better on an exception basis.

Fifth, suppliers — especially suppliers of products that are core to a global customer’s business —should guide the customer away from a focus on price alone and toward an emphasis on value enhancement combined with price.

Sixth, suppliers can promote value enhancement through more efficient logistics and inventory management, although most customers would consider only the top 5% to 10% of their suppliers as suitable for such coordination. Only those top suppliers sell the customer enough to enable lower costs through logistics and inventory enhancements.

Once the supplier has weighed the six success factors, it should adopt six behaviors that, according to our observations, ensure optimum preparation for global pricing:

- being selective

- aligning one’s account-management organization with the customer’s power structure

- recruiting appropriately

- compensating appropriately

- providing price flexibility and

- building information systems (See “Preparing for Success.”)

Gaining Mutual Advantage

Many global customers try to have it both ways. They want low global pricing from suppliers but prefer their own customers to accept prices based on costs and service. But when procurement consolidation occurs at one level of the value chain, the principle of countervailing power inevitably stimulates interest in global or regional contracts at the next level. Interestingly, in contrast to today’s focus on worldwide contracts, Ignacio Lopez, the former General Motors manager — known for, among other things, successful procurement — did not pursue GPCs. His attitude toward cross-border price differences was that GM suppliers should justify their pricing logic to their customers. Although he never obtained the same price for a Pirelli tire supplied in different parts of Europe, for example, he made procurement savings a source of value to his company in an era of corporate restructuring.

Ted Dalrymple, AMP Inc.’s global-marketing vice president, sums up the plight of vendors that manage global customers in a reactive mode: “Customers love a vendor’s global-account-management system because as soon as a global-account manager is designated, they see one person whom they can beat to death to get a lower price.”

Suppliers need to be masters of their own fate. Preparing for global pricing does not mean preparing to charge the same price everywhere — or to be beaten to death. It means establishing information-gathering and coordination processes that ensure the logic and sustainability of prices worldwide. A supplier-friendly GPC doesn’t have to inconvenience customers. Collaboration with suppliers has been shown to help some buyers save hundreds of millions of dollars.6 In most of those cases, customers first had a multifunctional team select suppliers; then they collaborated with suppliers to reach target prices. We believe that, with proper planning, a proactive approach and successful negotiating, a global-pricing contract can be a winning outcome for the supplier and serve as the foundation for a broader, mutually advantageous customer relationship.

References

1. “GM Powertrain Suppliers Will See Global Pricing,” Purchasing 124 (Feb. 12, 1998).

2. E.R. Silverman, “Adding Value Anytime, Anywhere — Channel Players Have Different Ways of Handling the Challenges of Offering VA Services Globally,” Electronic Buyers’ News, January 2000, 18.

3. C. Zarley and J. Rosa, “Going Global,” Computer Reseller News, Sept. 8, 1997.

4. S. Helper, “How Much Has Really Changed Between U.S. Automakers and Their Suppliers?” Sloan Management Review 32, no. 4 (summer 1991): 15–29.

5. S.C. Frey Jr. and M.M. Schlosser, “ABB and Ford: Creating Value Through Cooperation,” Sloan Management Review 35, no. 1 (fall 1993): 65–73.

6. D. Asmus and J. Griffin, “Harnessing the Power of Your Suppliers,” McKinsey Quarterly 3 (1993): 63–79; and

J. Stevens, “Global Purchasing in the Supply Chain,” Purchasing & Supply Management, January 1995, 22–25.