The Case for Standard Measures of Patent Quality

The current balkanized approach to measuring patent quality is not serving the users of the world’s patent systems.

Topics

An essential role of any government in supporting its nation’s scientific and commercial innovation is to define and enforce property rights.

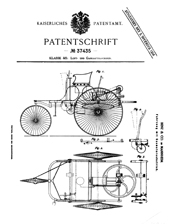

In the late 18th century, scientific inquiry was leading to major discoveries that fueled industrialization and increased international trade. At the time, nations relied on different systems of measurement developed in earlier eras of limited international exchange and communication of ideas. Lack of standardization posed an impediment to both scientific advancement and industrial growth. To address the problem, both the French and British governments considered reforming their systems of weights and measures and establishing a decimal-based measurement. In the newly formed United States, Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State and the country’s first patent commissioner, proposed such a system as well. Although the United States and Great Britain didn’t remain on this path, the French went ahead and adopted the modern metric system, which today is widely used in science, education and industry throughout most of the world.

Now fast forward to the Information Age. Today, intellectual capital and intangible assets — including technology, brands and strategic competencies — comprise more than 50 percent of the business outputs in the U.S. economy. Smart government policy worldwide encourages investment and growth in innovation, while balancing people’s needs for better and more affordable access. Although patent offices around the world implement their own country’s policy goals regarding intellectual property, they are also promoting innovation, globalization, trade and better lives for people everywhere.

Like those advocating for the metric standard two centuries ago, we have an incompatibility problem today in the international patent system. How the global patent system is organized and managed has far-reaching implications for innovation, consumer choice and corporate profits. Demand for patent examination is rising: In 2008, the most recent year for which good data are available, the World Intellectual Property Organization estimated the number of patents in force around the world at 6.7 million, with an increasing share of inventions being patented in more than one country. Unfortunately, there is no common “quality” standard. Like a patent Tower of Babel, the lack of a common language stands in the way of coordinating and building a useful common asset.

The current balkanized approach to measuring patent quality is not serving the users of the world’s patent systems. In fact, it blocks different offices from cooperating and sharing work product, thus preventing innovators from having a more efficient global system of patent protection and requiring the expenditure of more applicant fees and precious government resources at a time when both private and public budgets are under pressure. A rational approach to defining, measuring and comparing the output of our offices — a new “metric standard” for patent quality — would allow each nation’s patent office to promote their domestic policy aims while also participating in a standardized system, thus allowing patent offices worldwide to do a better overall job both in producing high quality output and supporting economic growth.

Why Patent Quality Matters

Every patent office says that “quality” is its number one priority. But when it comes to formulating patent policy, what is quality? If a country’s patent application allowance rate is very high, does that mean the patent office is not being sufficiently selective, or does it mean national lawmakers have made choices in favor of patentability to serve larger economic goals? If the allowance rate is low, does that indicate higher quality selection, or does it suggest that the technologies coming in the front door are less inventive? To be sure, part of the problem comes with the abstract nature of what patent offices seek to codify: A patent application is a complex legal document drafted as a series of claims that attempts to describe new and nonobvious processes, machines, manufacturing methods or composition of matter. Any document that attempts to describe a physical phenomenon that’s new to the world with mere words risks being challenged on its precision.

An essential role of any government in supporting its nation’s scientific and commercial innovation is to define and enforce property rights. Innovators create value by generating new ideas and bringing better products and services to market. It follows that offering greater certainty over IP rights to innovators and those considering investing in innovation would be a priority.

On the other hand, government leaders must balance many interests. Although society has an interest in maximizing certainty around patents to protect what belongs to the inventor, it also has an interest in properly protecting what is in the public domain. There are costs to society of getting the balance wrong, including over- or under-investment in innovation, unnecessary and wasteful duplication of creative effort and inadequate notice to the public about what activities are legal uses of technology and which are illegal infringements.

The reality is that none of the quality metrics that patent offices have used fully take account of the different views of the various actors operating within a country’s patent system. And when one looks at the international dimension of patents and the different economic perspectives from country to country, the problem becomes much more complicated. But it is precisely because innovation is a global concern that we need to make international comparisons about patent quality. In their efforts to gain increased patent protection, innovators are going to patent offices in multiple countries, which leads to escalating transaction costs on innovators operating globally.

Eliminating duplication on patent review processes for the same invention would strengthen the global innovation system. Between 1991 and 2009, patent applications to the United States Patent and Trademark Office surged 171%, from 178,000 to 483,000. Much of the work the USPTO does duplicates efforts being done elsewhere: Since 2008, more than 50 percent of U.S. patent applications have come from non-U.S. inventors. Much the same is occurring across the globe, contributing to larger and larger backlogs at the world’s patent offices. In 2009, the average time a patent application spent in the examination queue was 34.6 months in the United States, 35.3 months in Japan, and 41.7 months in the European Patent Office. Clearly, the demand for patent office services is swamping capacity, and it underscores the growing need for a common quality standard.

Normalizing for National Differences

Fundamentally, each nation has its own approach to patenting. In the United States, policymakers — Congress, the president, and the courts — have given broad scope to patentable subject matter, covering every new idea that is not “abstract” (which according to the Supreme Court includes “anything under the sun that is made by man”). In the 1980s, the U.S. government extended patent protections to the life sciences before other governments were prepared to address this area of innovation, and the U.S. biotechnology industry flourished.

The U.S. system differs from those of other nations in other important ways: The government requires applicants to disclose useful information such as relevant prior art; it establishes low fees — especially for small entities — to encourage entry into the patent system; and perhaps most importantly, it creates an enforcement regime that is more favorable to patent holders than anywhere else in the world. If damage awards in litigation are a useful indicator, other systems produce a lower value product than the United States in terms of enforceable rights. The patent laws of other countries reflect different priorities, often placing a premium on certainty and limitations and yielding more restrictive patent grants.

Our purpose here is not to advocate for a single approach or one approach over another. Governments need to decide for themselves which patent system suits their overall national interests based on their economic objectives, educational system and goals for long-term employment, capital investment and other factors. While we must acknowledge the differences, we should not allow these differences to prevent us from operating more economically and reducing transaction costs to users of the global system. And the first key step to such collaboration is a common system of measurement.

How do we begin to build a common view of quality? The USPTO set out to address this issue in 2010. Recognizing that no single measure was adequate, we invited interested parties — corporate managers, patent attorneys, inventors and scholars — to provide feedback on appropriate measures. After conducting public hearings and looking at numerous proposals, the USPTO announced a set of seven new quality metrics in September 2010. These new metrics encompass the effectiveness of prior art search and examination, compliance with best practices and procedural rules during patent examination, and a statistical analysis based on quality-related indicators and surveys conducted of both applicants and examiners. By using an array of inputs rather than just one, our goal is to improve the predictability of our measure.

The new USPTO metrics have been in place since October 2010, and the early results have been encouraging. They have allowed the USPTO to triangulate on a measure that better reflects the true quality of our process while also helping us understand the quality of incoming patent applications (our inputs) and patent grants (our outputs). To be sure, our approach defines U.S. patent quality within the context of U.S. laws and regulations. Yet the U.S. focus of these new metrics highlights an important issue any serious effort to assess patent quality more broadly must deal with: The national systems we’re trying to normalize across are just different, and the solution will require dealing with the differences.

A New Metric for Quality

What is needed, but does not yet exist, is an approach that normalizes for the differences in patent laws and regulations across countries as the basis for meaningful quality comparisons. It would account for the aspects of patent systems that allow for more or less precision, and for differences in industrial policy. We cannot reasonably expect that patent offices around the world will subscribe to each other’s rules anytime soon. But rather than focusing on the impediments that such differences present, it may be more productive to work toward normalizing for the differences. By focusing on developing standard measures, patent offices worldwide can uncover the specific opportunities and limits of worksharing in search and examination.

The world’s patent authorities cannot just keep doing the same thing and expect different results. The explosive growth in patent applications worldwide and the increasing backlogs provide strong reasons for moving in a more collaborative direction. The fact is that different patent offices already use many of the same concepts, even though they may use them in different ways. For example, Europe, Japan, and the United States all use similar “inventive step” requirements for patentability (called “nonobviousness” in the United States). They should be able to use other similar requirements as building blocks to establish comparable standards. We recommend the following first steps:

1. Recognize that leadership matters. Serious efforts at normalizing for different laws and practices must be supported from the top of the organization and not left to periodic perfunctory discussions that have produced too little progress in the past.

2. Pursue early successes by focusing on areas that could yield large benefits. Many offices already share similar standards related to accuracy in searching for all prior art and in making novelty and obviousness determinations in technologies over which there are few debates about what is patentable subject matter. Fortunately, these are by far the most important parts of the examination process in most cases.

3. Rely on independent analysis using relevant information. Neutral professionals — not cheerleaders — should conduct robust analyses of the differences in laws and practices and recommend ways to calibrate the standard, using the best and most up-to-date information available.

4. Account for errors in both directions. Any serious effort at measuring quality must account for mistakes made in granting patents erroneously as well as in failing to grant patents that should have been granted.

The potential payoffs of standard measures are clear: By allowing increased worksharing for examination and search, patent offices could charge innovators lower fees and provide faster patent examination not only to their own national users but to the international innovation system at large. Common measures would allow governments to focus on the laws and regulations that can pay the largest dividends and make better decisions affecting international harmonization. In an increasingly global innovation market, with inventors seeking patents around the world, common metrics would allow patent offices to provide efficiencies on both sides of the equation: Inventors would have greater access to global protections, and patent offices would be able to reduce costs and offer better services.

The 19th century has been called the “century of industrialization.” It ran on standardized ribbons of steel, with factories churning out products built upon laboratory advances that were enabled by standardized measures. What standards will we rely on in our own, a century propelled by knowledge and intangibles? Unless we have the ability to measure quality in intellectual property rights and permit investments and markets to work efficiently, we may not get to the better world that ingenuity and the human spirit are able to produce.