Workforce Ecosystems

A New Strategic Approach to the Future of Work

Executive Summary

Ask managers today how they define their workforce, and a common answer is, “That’s a very good question.” It’s a good question, managers tell us, because they feel often squeezed between two realities. One reality is that their workforce increasingly depends on external workers. The other reality is that their management practices, systems, and processes are designed for internal employees. The struggle to reconcile these two realities is an ongoing challenge, with significant implications for strategy, leadership, organizational culture, and workforce management practices.

Our research makes clear that most managers today consider employees and other workers who create value for the enterprise — including contractors, service providers, gig workers, and even software bots — to be part of their workforce. Our recent global executive survey affirms that the vast majority — about 87% — of respondents include some external workers when considering their workforce composition.

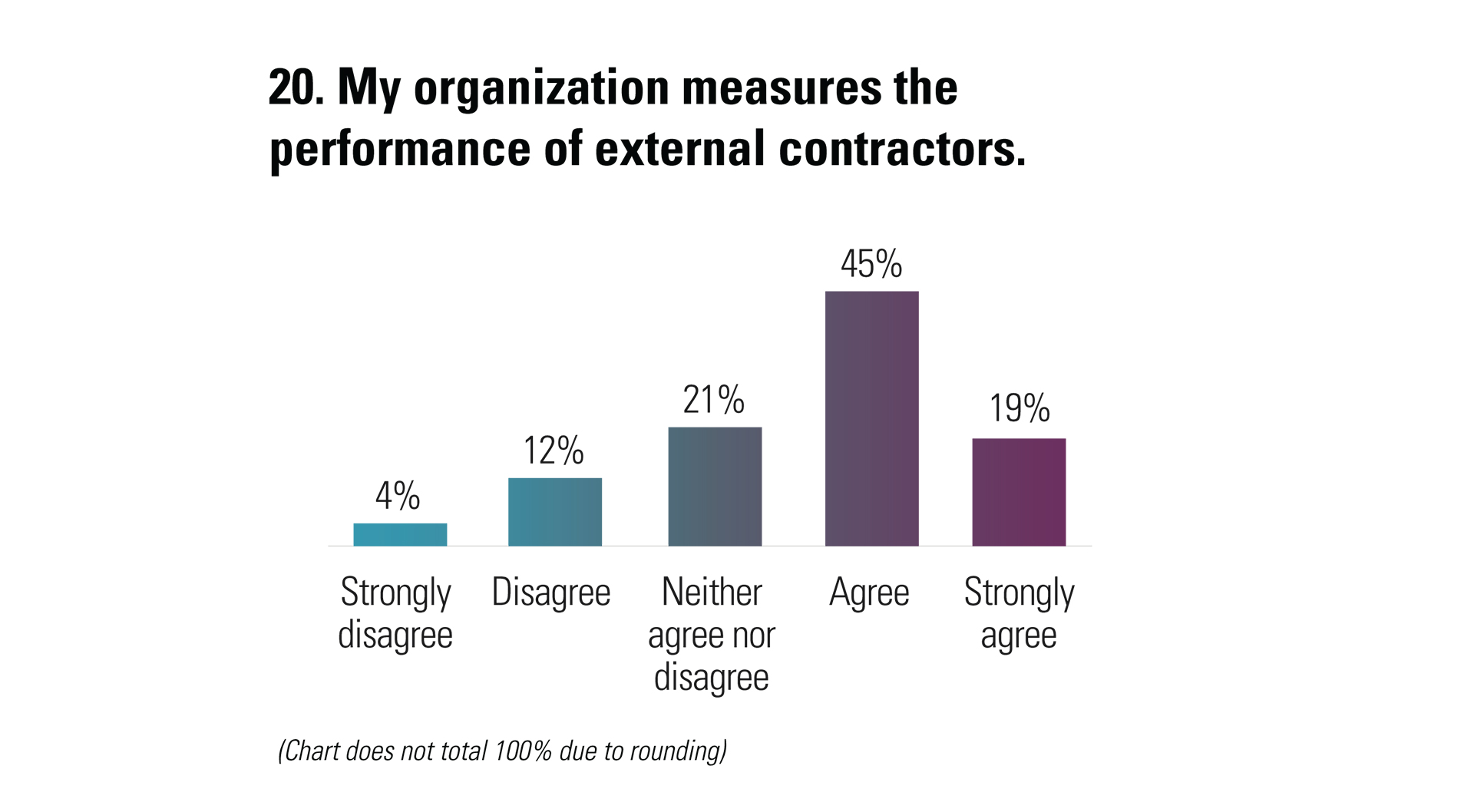

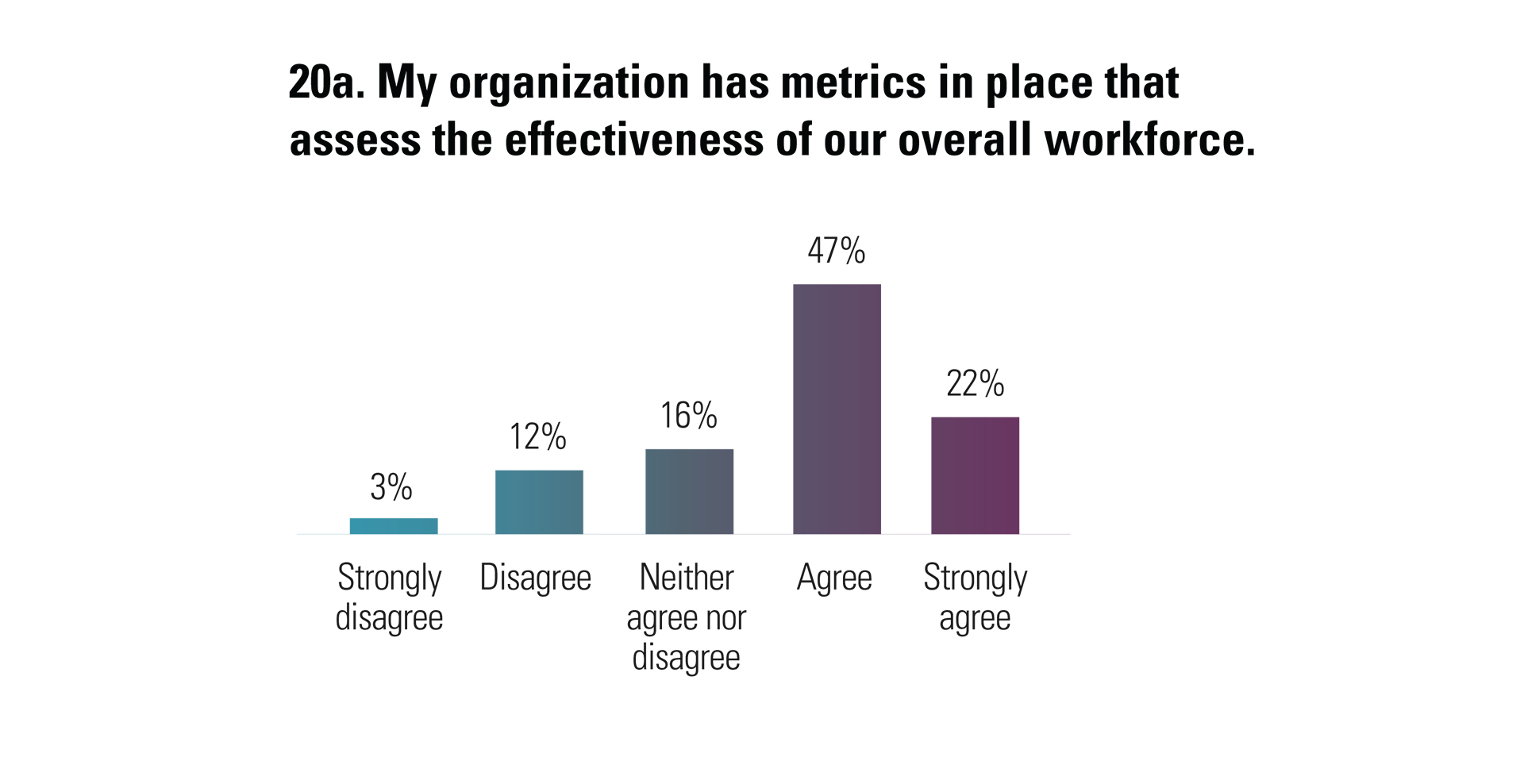

At the same time, most workforce-related practices, systems, and processes focus on employees, not external workers. Workforce planning, talent acquisition, performance management, and compensation policies, for example, all tend to focus on full-time (and sometimes part-time) employees. Consequently, organizations often lack an integrated approach to managing a workforce in which external workers play a large role.

As one of the executives we interviewed for this report told us, “Wouldn’t it make sense to become just as mature about managing this segment of the workforce, which can be even bigger than your payroll workers?”

The search for an integrated approach to strategically managing a diverse group of internal and external workers has led some forward-thinking executives to the idea of a workforce ecosystem.

We define a workforce ecosystem as a structure focused on value creation for an organization that consists of complementarities and interdependencies.1 This structure encompasses actors, from within the organization and beyond, working to pursue both individual and collective goals.

This promising idea — which we discuss in detail in this report — offers several potential benefits that could help managers think through the strategic, organizational, regulatory, and practical implications of a workforce comprising employees, external workers, and others.

This report explains what workforce ecosystems are, reflects on the trends driving their emergence, discusses their benefits and challenges, and identifies shifts in management practices associated with creating and managing a workforce ecosystem. Our discussion is based on findings from a recent global executive survey of 5,118 professionals, 27 executive interviews, and a review of human capital and ecosystem management literatures.

This research is part of a multiyear MIT SMR and Deloitte research collaboration on the future of the workforce.2 Our research to date offers compelling evidence that many of today’s executives expect workforce ecosystems to be a significant part of their futures. It is an open question whether the trends that have been moving companies toward workforce ecosystems — such as the changing nature of work, and shifting worker preferences — will continue to drive companies in this direction.

Introduction

Concentric rings, a continuum, a community, a patchwork — these are a few analogies that leaders turn to when considering the broad range of workers who create value for their organizations. Today’s workforces increasingly comprise an array of players, including not only employees but also contractors, gig workers, service providers, external app developers, crowdsourced contributors, and more. British multinational creative company WPP, for instance, has more than 100,000 employees and relies on several hundred thousand freelancers. WPP visualizes its workforce as concentric rings. Global chief people officer Jacqui Canney notes that, when thinking about culture and career building, the company doesn’t limit itself to the innermost rings. “We’re not going to just think about the hundred thousand people,” she says. “We’re going to think about the outer rings — the over 500,000 people that touch a WPP client.”

Enterprise software company Workday uses a continuum analogy. Barbry McGann, executive director of Workday’s Office of CHRO Solution Marketing, says, “We are seeing an emerging workforce continuum that includes work from nonemployees such as contingent workers and freelancers, to contributions from employees who include both hourly and salary workers.”

Even an organization as steeped in tradition as NASA is finding conventional workforce conceptions insufficient. Nicholas Skytland, deputy chief of NASA’s Exploration Technology Office, sees its future workforce as encompassing both “somebody who loves their job so much they will stay for a 30-year career and the project-based gig worker who works at NASA for a season, possibly while also working at multiple other jobs at the same time.” Skytland contends that NASA’s future workforce also includes citizen scientists contributing their talent to the agency’s mission through events such as the annual International Space Apps Challenge or NASA’s many other open innovation platforms.

Applause is especially reliant on external actors and views its workforce as a community: It is a software testing company that doesn’t count a single software tester among its 400 employees. Instead, the company’s crowdsourced community — 700,000 strong, from 200 countries and territories — does its testing work. Founder, chairman, and CEO Doron Reuveni sees great benefit in this workforce model. “It’s much better than hiring someone to do a job,” he says. “Here, you actually have data about what that person did — which projects they worked on, which bugs they submitted. You have real data on their value.”

Catherine Popper, an angel investor and board member at Launchpad Venture Group, uses a patchwork metaphor to describe how startup ventures with limited resources use a variety of talent arrangements to get work done. “You end up thinking about all of the various ways you can use talent: part-timers, temps, the platforms, the agencies, the remote developers, advisers, your lawyers, your bankers,” she says. “Every hire that a startup makes is a financial bet. Having a bigger patchwork allows you flexibility.”

Contributors are not limited to freelancers and gig workers; they also often include external organizations. Amazon has more than 1 million employees, but more than 2 million independent business owners offer merchandise in the Amazon Marketplace, according to Jeff Wilke, the company’s retired CEO of consumer business. Those sellers, though independent, complement Amazon’s business in the sense that they add value to Amazon Marketplace.

Are these stories typical or atypical? We interviewed 27 leaders from business, academia, and government and conducted a global survey of 5,118 managers and executives. Our research clarifies the extent to which companies are orchestrating internal and external contributors as well as external organizations. Our survey found that 87% of respondents define their workforce in broader terms than just full- and part-time employees. (See Figure 1.) This MIT SMR and Deloitte 2021 Future of the Workforce report proposes a workforce ecosystem approach to address this challenge. In this report, we:

- Explain the workforce ecosystem concept and highlight several forces driving its emergence.

- Discuss how workforce ecosystems may influence strategy; leadership; culture; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and workforce governance.

- Identify important management practice differences between a workforce ecosystem approach and the traditional employee life cycle model.

This project extends our collaborative multiyear research initiative on the future of the workforce.3 Based on our cumulative pre-2020 work and current research, our evidence strongly suggests that the trends driving workforce ecosystem adoption were happening before work-related shifts associated with the COVID-19 global pandemic and will likely continue as extreme conditions related to the pandemic subside.4

Beyond an Employee-Based View of the Workforce

Leaders are beginning to think more expansively about who is in their workforce; many expect more external workers to be part of their workforce in the future. (See Figure 2.) Some are even thinking structurally about what their workforce is, and we see an increasing trend toward a workforce ecosystem approach. Several interviewees already describe their workforces as ecosystems. Reuveni says that Applause’s large community of software testers “is really an ecosystem.” IBM chief human resources officer (CHRO) Nickle LaMoreaux says that the technology company thinks of its expanded pool of workers as “the broader ecosystem,” for example. WPP’s Canney says the company considers its full-time workers and its freelancers to be “part of our ecosystem.” Nike’s former vice president of human resources Karen Weisz calls the total workforce “an expanded ecosystem.” These executives are already thinking about their workforces in an integrated way.

Building upon our data and recent management research, we define a workforce ecosystem as a structure focused on value creation for an organization that consists of complementarities and interdependencies.5 This structure encompasses actors, from within the organization and beyond, working to pursue both individual and collective goals. By complementarities, we mean that some members of the system (workers or organizations) work independently yet together offer value for their mutual customers. By interdependencies, we mean that some members rely upon one another for their shared success (or failure); they win or lose together.

This ecosystem approach is a significant departure from the traditional view of the workforce, which envisions individual employees performing work along linear career paths to create value for their organization. Where the traditional workforce perspective establishes a human resources structure for managing employees, replete with systems, processes, and oversight, this new approach treats the workforce ecosystem itself as a structure. Managing employees and managing a workforce ecosystem structure are fundamentally different processes.

Workforce Ecosystems Include a Broad Community of Workers and Organizations

A workforce ecosystem includes both employees and external parties that don’t work directly for an organization yet may be integral to its success. Ecosystem members — whether individuals, companies, or technologies — might have interdependent and/or complementary relationships. Together, they make up a diverse community that an organization builds, nurtures, grows, and leverages to meet its objectives.

For example, Wilke explains the logic behind the decision to open Amazon Marketplace, which resulted in 2 million third-party sellers: “We could have continued to operate our own store very successfully, but we thought it would be better for customers if we allowed competitors, including small businesses, to offer their wares alongside ours. That benefits everybody.”

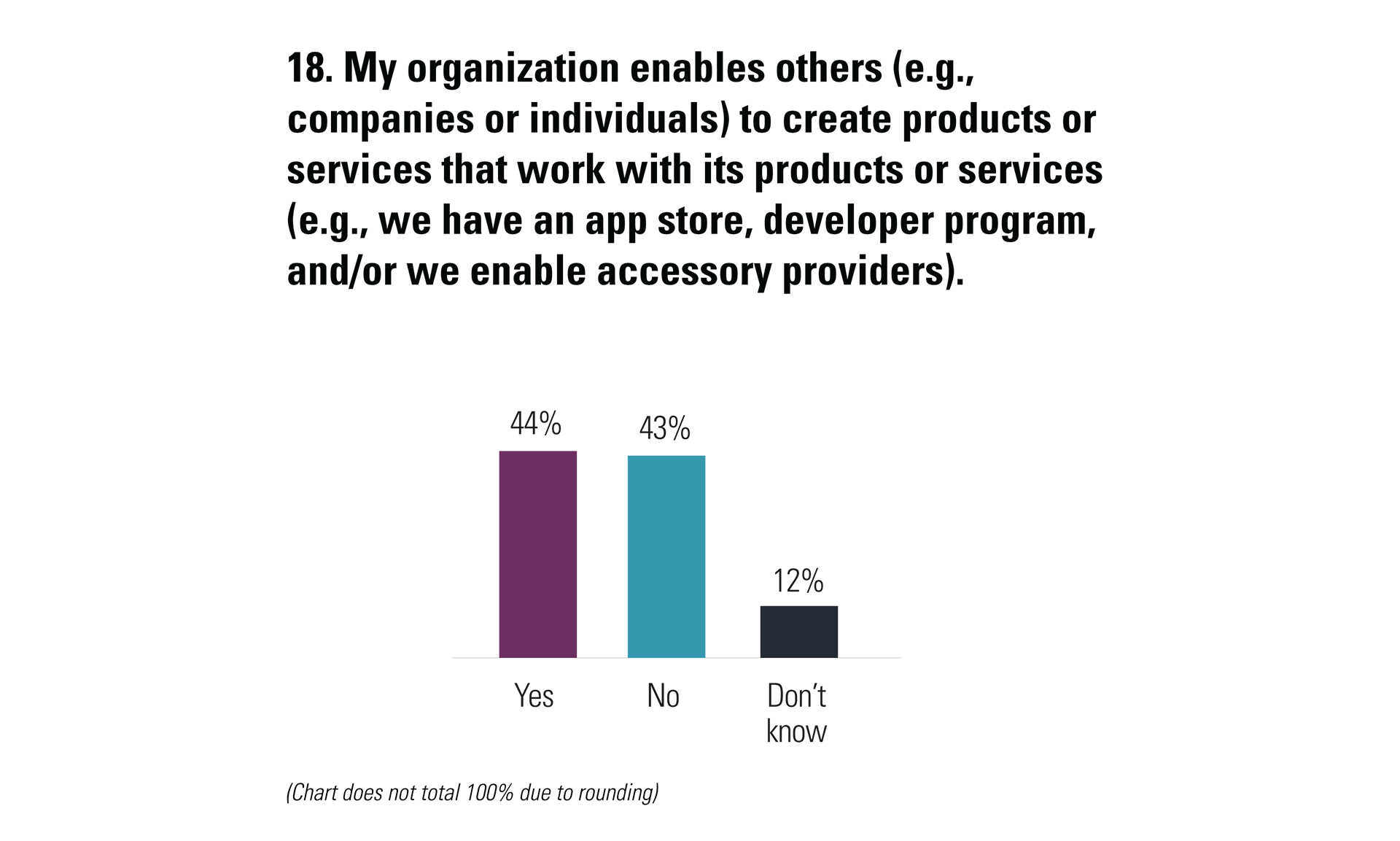

Alan Trefler, founder and CEO of Pegasystems, also sees advantages to including complementors as part of the software company’s strategy, a trend he believes is on the rise. Optimizing the workforce, he says, isn’t just about “helping you assign and manage work seamlessly across your enterprise. It’s also about being able to reach into the enterprises of others and bring the work they might be doing into a common channel for your client. I expect to accelerate our involvement with partners who offer complementary technology to what we deliver.”

The workforce ecosystem may include individuals who do not currently create value for an organization but are potential workers. At Applause, only 25% to 30% of the company’s 700,000 software testers work on paid projects at any given time. The rest have the opportunity to build skills and gain experiences regardless of whether they are participating in paid work. Meanwhile, Applause aims to build loyalty, trust, and a sense of community and belonging among ecosystem members — an effort that transcends traditional notions of employee engagement.

In a very different organization, the U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. Ronald Clark, chief of staff of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, considers not only military, civilian, and contracted personnel to be part of his workforce, but families as well. “I include our families,” he says, “because a lot of work in and around units is done by volunteers through soldier and family readiness groups.”

Including organizational alumni and retirees, sometimes referred to as boomerang employees, is another way to augment workforce ecosystems.6 IBM’s LaMoreaux notes that “it’s important, as you think about the life cycle of an employee, to know that there will be entries and exits, and you need to be thinking about how you manage that and provide engaging experiences at every point.”

Elizabeth Adefioye, senior vice president and CHRO at Ingredion, says the multinational ingredient provider occasionally brings back alumni for part-time work “because we need a particular critical skill or competency.” Similarly, we have seen overwhelmed hospitals worldwide ask retired health care professionals to return to help treat COVID-19 patients; tens of thousands have answered the call.7

With a workforce ecosystem approach, organizations may also share employees or other workers with other ecosystem members to fill short-term gaps. This has myriad cost, time, and opportunity benefits for workers and organizations. Brian Baker, global people strategy business partner at WPP, describes how clients with openings in marketing functions have asked WPP to lend them employees to fill slots for a specific period. In these cases, WPP and its clients become part of each other’s ecosystems. “We give the employee an actual experience of someone they serve every day and have our own people growing our clients,” Baker says. “And then, for our clients, it’s not only a cost play, but it’s a total rethinking of their own gig mentality, because they know they have a trusted partner who has a track record of delivery. And it’s reliable and easy.”

Workforce Ecosystems Recognize That External Workers Are Doing More, and More Significant, Work

Across industries, external actors and businesses are doing a significant share of organizations’ work. Cris Wilbur, chief people officer at Roche, estimates that contingent (i.e., nonpermanent) workers account for approximately 25% of the Swiss health care multinational’s total workforce. McGann says that some of Workday’s customers have workforces that are as much as 50% contingent. Arun Srinivasan, general manager of software company SAP Fieldglass, which helps clients manage their contingent workforces, notes that “if you look at certain industries like energy and natural resources, financial services, and technology, you will be surprised that often there are more external workers than employees in a given time period.”

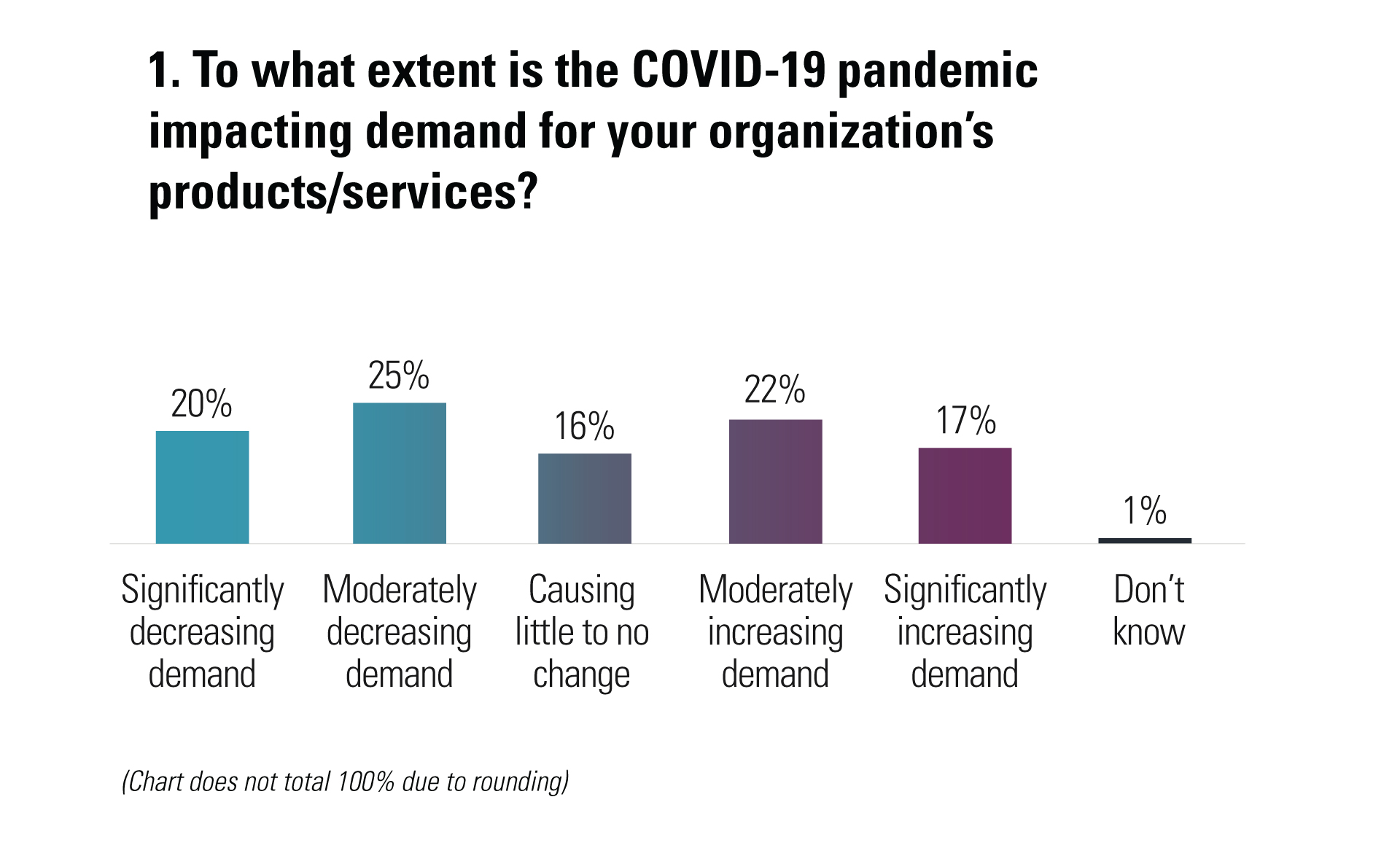

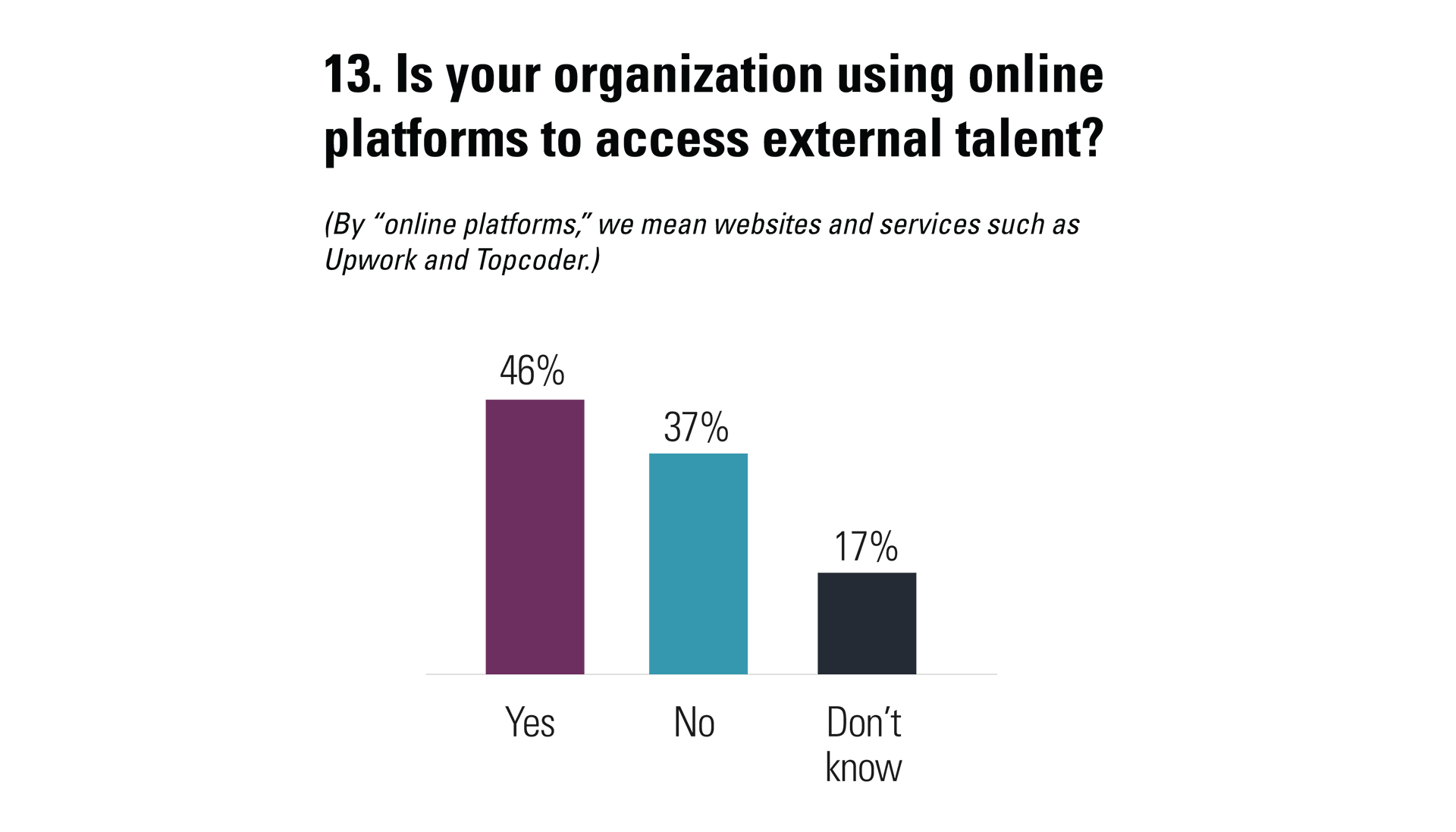

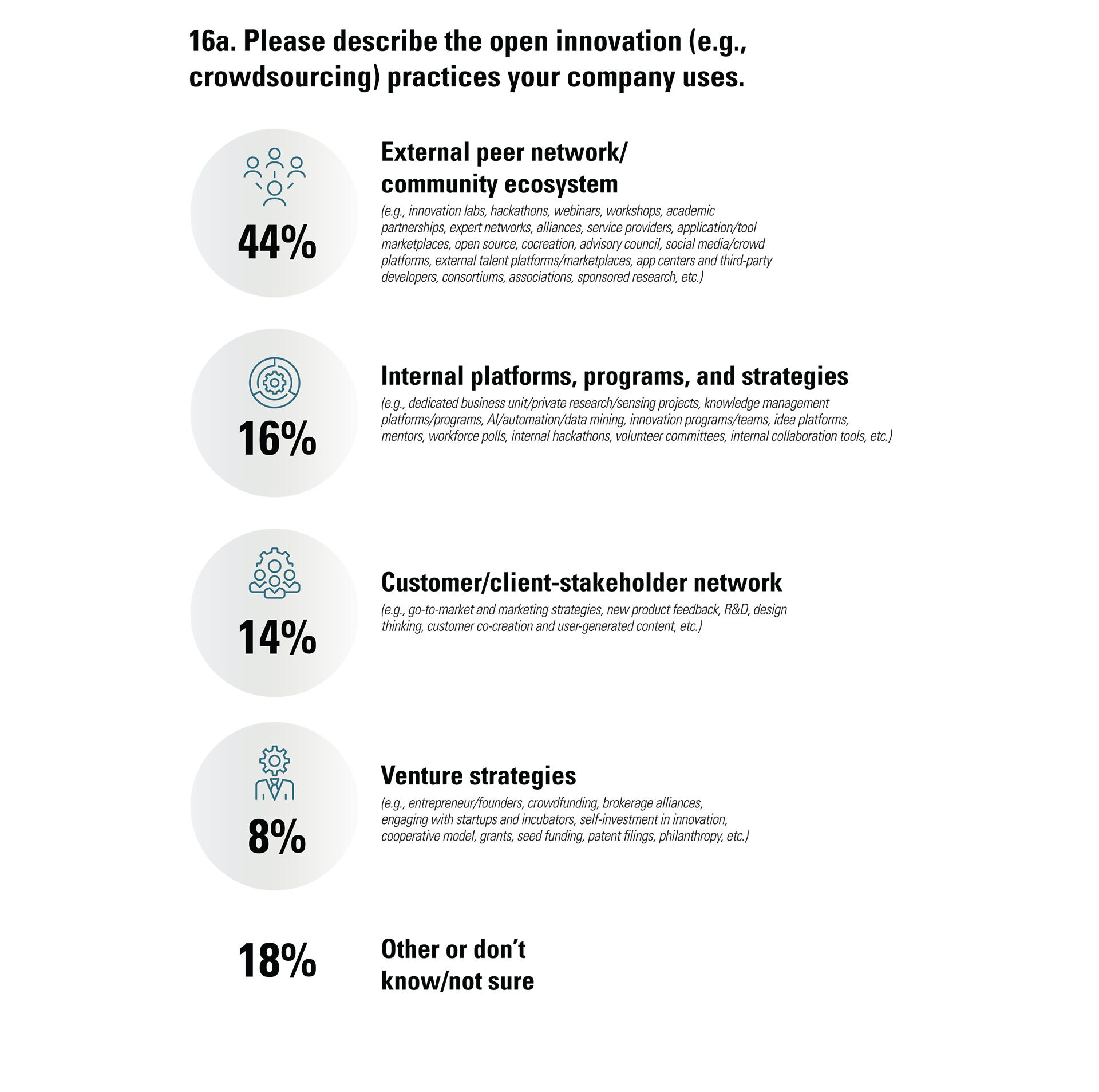

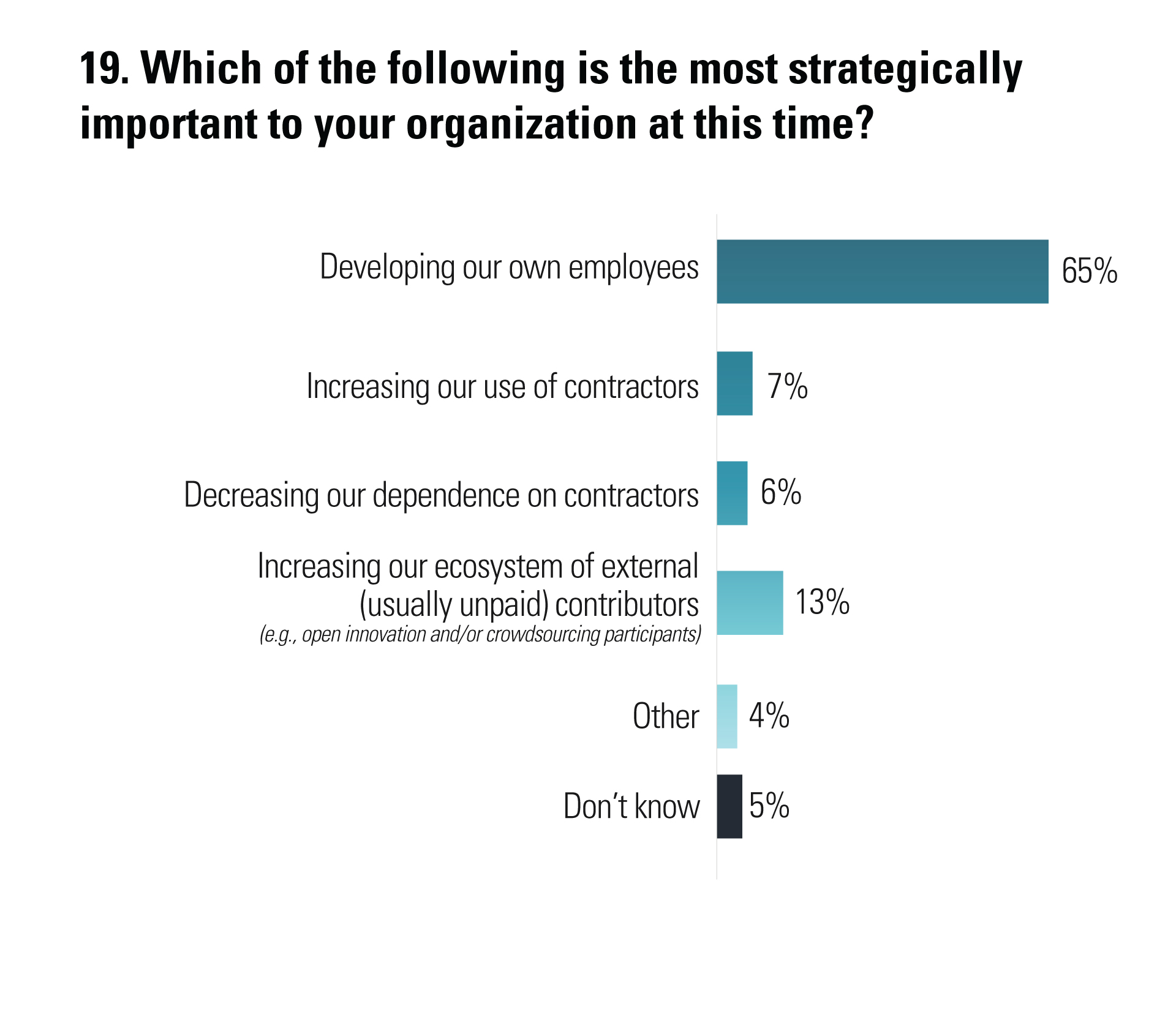

Our survey data suggests that a substantial number of respondents believe their workforces are moving in this direction. A third of our survey respondents (33%) expect to increase their dependence on external workers in the next 18 to 24 months. This holds true regardless of whether managers agree that demand for their organization’s products or services have been positively or negatively affected by the pandemic. Adefioye is acutely aware of the importance of external actors to Ingredion. “Today you have temporary workers, contingent workers, consultants, full-time employees, and those that are job-sharing,” she says. “We have to be prepared for all of those types of workers, because they bring different value.” Our research shows that more than half of organizations expect to increase their use of online platforms to access external talent. However, few are preparing to manage a workforce that depends increasingly on external participants. (See Figure 3.)

External workers are not only doing more work; they’re doing work of more importance, too. The contingent workforce is often essential to an organization’s core mission. As Srinivasan explains, “We’re seeing organizations embracing the concept of engaging third-party providers and external talent for those highly differentiated services that they need to survive and thrive as a business.” Other research supports this observation.8

Similarly, Roche sees its workforce in terms of the entire range of contributors who help accomplish its mission of delivering innovative medical solutions. “We have been thinking about our workforce in a much more inclusive, holistic way,” Wilbur says. Beyond employees, that newly defined workforce includes, for example, “contractors who are working with us because we need specialized expertise and partners that provide us certain skills in a flexible and scalable way.”

Launchpad’s Popper says that filling vital roles externally has long been routine for startups. With limited resources, a startup might not be able to afford a full-time CFO, for instance, but it might have someone come in once a week to act as CFO. Popper has noticed that these days, more established companies are functioning this way too. “Can you use another resource to accomplish something that is better done by somebody other than your full-time employees? It’s easier, and it’s more high quality, to do it that way now than it was in the past,” she says.

Drivers of Workforce Ecosystems

Organizations relying on a variety of actors to capture and deliver value isn’t new, although the scale at which it is happening is. This growth has been driven by several significant shifts that profoundly alter the way many organizations address talent needs. The nature of work is changing, the preferences of workers are evolving, and technology is transforming how many organizations engage with and manage their workforces.

The Nature of Work Is Changing

The mechanistic, process-driven view of work focused on optimizing job performance has largely given way to a team-based, project-based view of work that’s focused on speed, innovation, and relationships. These changes are compelling some leaders to make new decisions about how to orchestrate their workforces.9

The transition to project-based work creates new requirements and opportunities for organizations to bring in external talent for specific engagements or to use internal talent marketplaces that enable employees to move easily among departments to meet emergent demands. Pegasystems’ Trefler declares that “the right way to think about a workforce of the future is to think about the work. What is it you’re trying to achieve? When you start by looking at the work, then you get to really look at the problem from the center out. What are the core elements of work, and which of those core elements should be done by staff who work for me?”

In addition to more project-based work, many organizations are also increasingly open to remote work arrangements, fueled in part by COVID-19 lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. Relatedly, starting long before the pandemic, researchers had begun studying the “work from anywhere” trend, addressing corporate real estate costs, immigration constraints, potential efficiency increases, and other related issues.10

Together, these trends improve the conditions for workforce ecosystems in several ways: They enable the relaxation of geographic constraints for organizations looking for workers, they permit workers looking for opportunities to search beyond their local areas, and they allow organizations to more easily match project-based demands with appropriate types of workers.

Workers’ Preferences Are Shifting

Many of our interviewees have observed that workers across all generations are prioritizing purpose, flexibility, and personalized experiences over job stability and security. Lynda Gratton, professor of management at London Business School, and Andrew Scott, professor of economics at London Business School, recognize that people across generations are changing their expectations for their careers, noting (in a coauthored article) that “individuals are starting to experiment with new stages of life and creating different career structures.”11 These new paths, including aligning lifestyle with work style, upgrading skills, and working beyond age 65, are well supported within a workforce ecosystem approach.

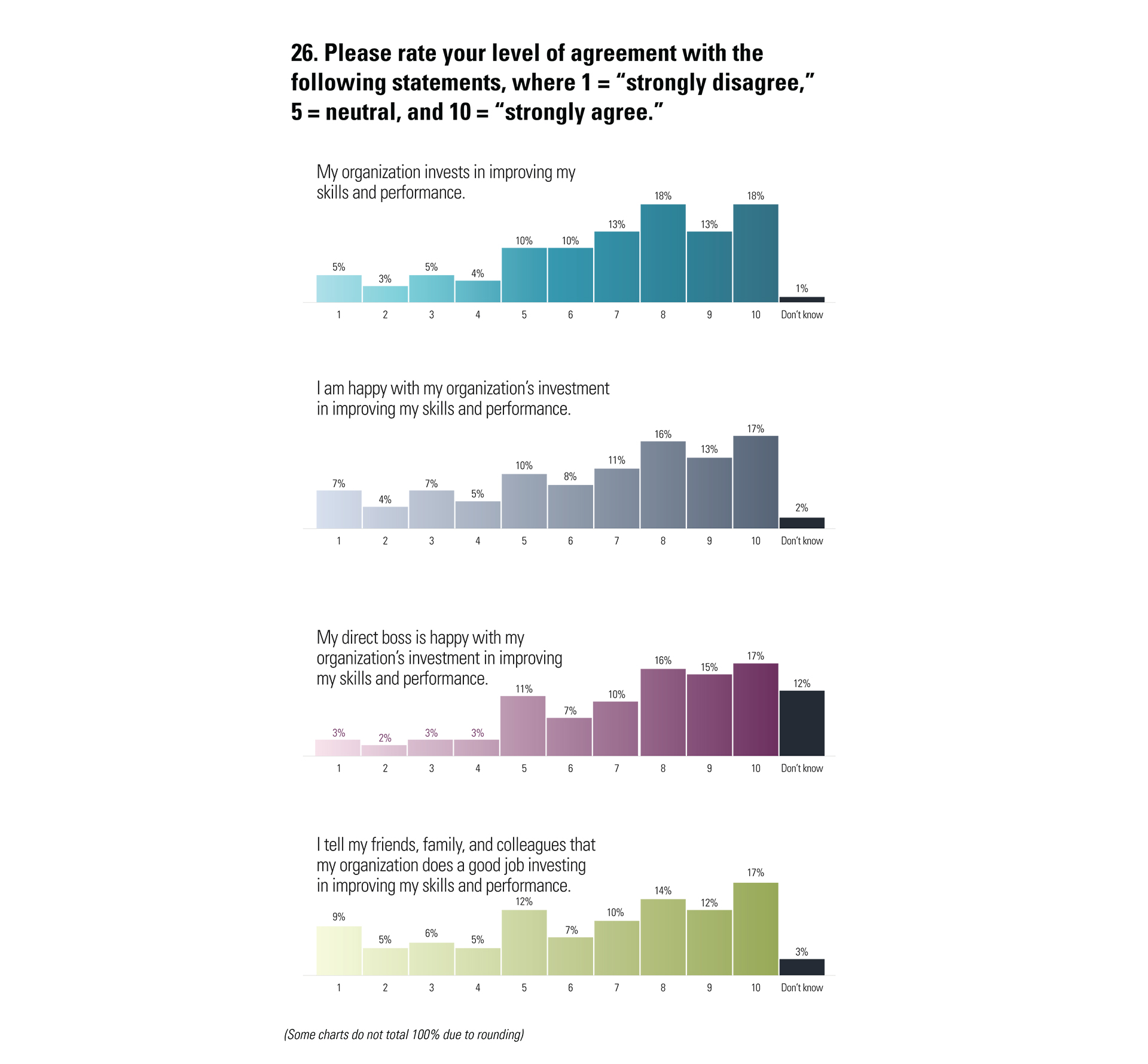

Launchpad’s Popper believes that for millennials, for whom corporate values are a preeminent concern, “tenure and longevity and loyalty are a thing of the past. That generation will vote with their feet. If they don’t like what they’re seeing, they’ll leave.” In fact, our research shows that many workers consider themselves to be “free agents” rather than “loyal employees,” even when they are permanent employees. (See Figure 4.) U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Milford H. Beagle Jr. notes that younger generations of recruits “want autonomy, purpose, and motivation. The early generations preferred the continuity and stability — the fact that ‘I’m here and have thrived in this environment; I’m stable.’ I think that with future generations, like the current one, you’re going to have to keep them challenged.” Workday’s McGann adds, “Employees value growing their skills and their capabilities. They want more projects and more gigs to build career currency through experiences, rather than climbing the ladder.”

Notes SAP Fieldglass’s Srinivasan: “Workers who are just joining the workforce and workers who are perhaps toward the last segment of their careers are both expressing a desire to engage in a different way. They’re saying, ‘I want to do meaningful work. I want purpose behind that work.’”

Technology Is Transforming How Many Organizations Engage With and Manage Their Workforces

Technology is essential to enabling workforce ecosystems (such as by improving internal talent management systems and external labor platforms) and providing tools that enhance value (such as through data analytics, AI, or machine learning).12

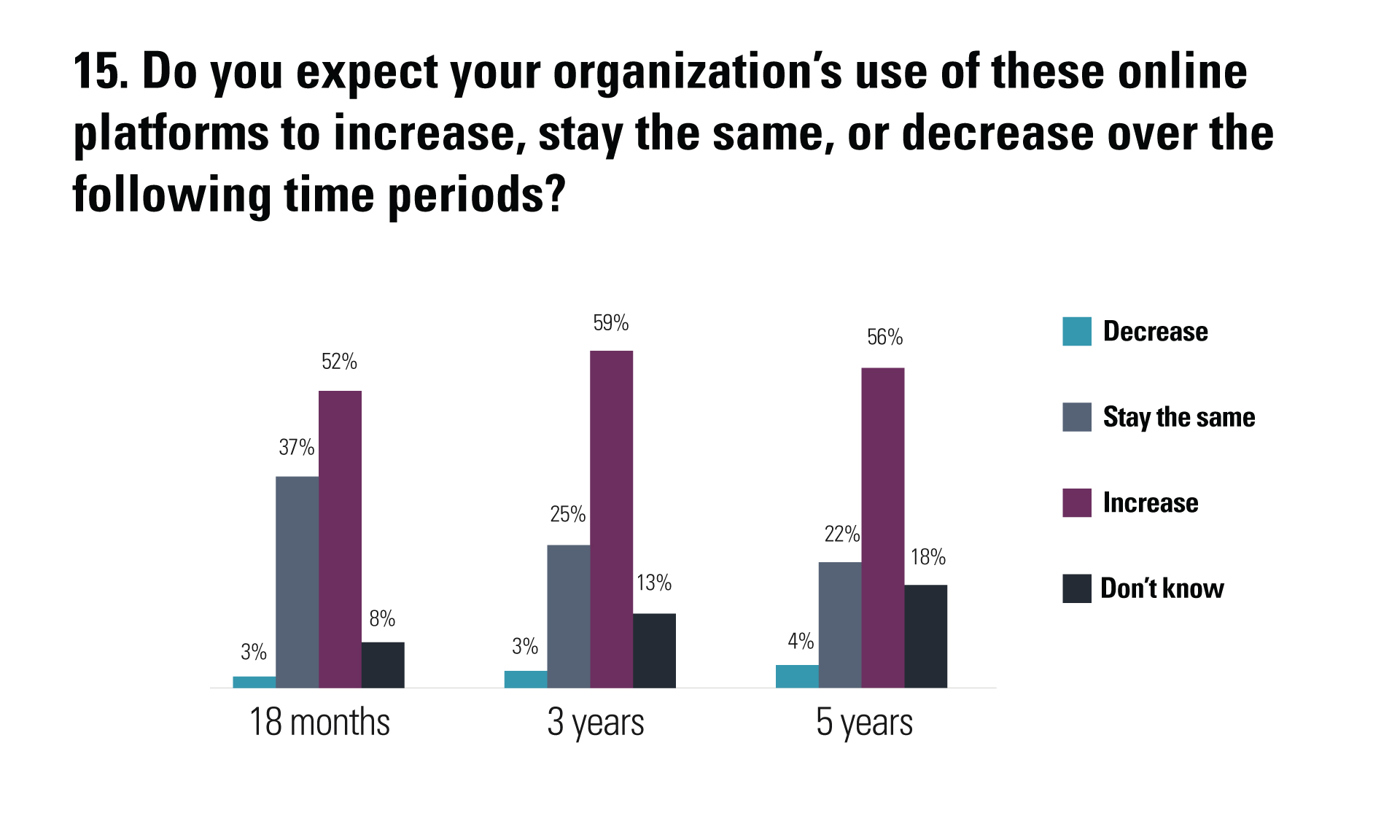

Gretta Corporaal, a research fellow and British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at Oxford’s Saïd Business School, points to the rise of online labor platforms, which make it easier and less expensive for organizations to find and engage external workers on demand. Corporaal is part of Oxford University’s iLabour Project, which developed the Online Labour Index, an economic indicator that tracks trends in online labor.13 “Over the last three years, we’ve seen that it has increased year on year on year,” she explains, noting that 30% of Fortune 500 companies use online labor platforms to find expertise they lack internally. “We think this is a trend that will continue to grow,” she adds. This data is consistent with our survey results: 52% of respondents expect their organizations to increase their use of such online platforms during the next 18 months.

Donna Morris, chief people officer at Walmart, recognizes that platforms are a source of talent and skills for a variety of needs, not only for short-term gigs: “You can use a platform to engage those services for the needs that you have, whether they be very transitional in nature or longer term.” Launchpad’s Popper highlights the changing role that these platform technologies play within workforce ecosystems. “It’s just dramatically easier to find the people,” she says. “All the tech enablers that allow you to find and then work with people anywhere are dramatically different.” Additionally, while these technology trends are benefitting many organizations by increasing their capabilities and access to resources, these same technologies are also helping workers by making it easier for them to develop and market their skills to hiring organizations.

Beyond providing the infrastructure that is powering workforce ecosystems, technology — both hardware and software — can also be a “worker” itself, performing or assisting with tasks. Amazon has 200,000 physical robots working among its human warehouse workers. This is also the case at NASA. “At NASA, the space agency has virtual bots that can be thought of in some ways as employees,” Skytland says. “To integrate with our IT systems, bots are given unique IDs when issued virtual employee badges.”

Workforce Ecosystem Characteristics

Workforce ecosystems may vary considerably from one organization to another, but they all have several characteristics in common: They enable value creation, they rely on complementarities between ecosystem members, and they include interdependencies among participants such that workers depend upon each other for their success or failure.

Integrated Structures That Create Value

Every organization’s overriding goal is to deliver value to its stakeholders. Workforce ecosystems enable organizations to create and capture value by coordinating workers and contributors of all types; they build communities consisting of workers interacting with the organization and with one another. However, given the scope and complexity of all of these interactions, management of these engagements is often fragmented and highly decentralized. A workforce ecosystem perspective offers visibility into the entire workforce, deepening managers’ perspectives on who is creating value for the organization.

The COVID-19 pandemic led Nike to realize that it needed to better understand and manage the workforce structure it had in place, Weisz notes. “We all woke up one day in March 2020 realizing we could not show up on our campus or in our places of work in the way we could the prior week,” she explains. “We began figuring out how to handle things like pay continuity, absenteeism, and need for leaves of absence for those employees who couldn’t work remotely, like our teammates in distribution centers and Nike-owned production facilities. But we quickly realized we needed to consider our contingent workforce as well. That was the initial impetus that really drove us to say, ‘OK, so how big is that box? Do we know who and where they are? Can we find them quickly if we need to?’ And when we say we want to do the right thing for our extended family of Nike workers, are we all defining that family the same way?”

Some organizations are already predisposed to using a workforce ecosystem approach, such as those accustomed to dealing with fluid (transient and often shifting) populations and those that have a clear mission, such as the military, research institutions, and universities. They tend to have systems in place to address many types of workers and keep a steady focus on their key goals and objectives. We have also found that organizations may have more than one workforce ecosystem, depending on their overall size, scale, and scope. For example, a consumer-facing division may be coordinating one ecosystem while an enterprise-focused division is managing another.

Complementarities Strengthen Workforce Ecosystems

Complementarities are essential to workforce ecosystems because they represent how distinct players can work independently while together providing value for mutual customers.14 Mayo Clinic, for instance, explicitly embraces an ecosystem approach that relies on complementarities to accomplish its mission. Mayo is a nonprofit academic medical and research center with many geographically dispersed doctors, nurses, scientists, and administrative staff. Its Mayo Clinic Innovation Exchange connects external entrepreneurs with internal innovators to advance breakthroughs in health care. Jared Mueller, the exchange’s director, notes that its mandate is consistent with the clinic’s overall workforce approach.

“We think of ‘workforce’ in a really holistic way that includes our own workforce but also goes beyond in terms of other actors that will help improve patient care, both within Mayo and across the world,” Mueller observes. “It’s a complex workforce, but we’re not just focused within a walled garden of our close to 70,000 staff. We’re really excited about a strong workforce of collaborators who might be on the other side of the world. We are about the mission, and the mission is accomplished in partnership with a lot of people who have many different email domains.”

Interdependencies Link Successes Within Workforce Ecosystems

The entities within an ecosystem rely upon others to get work done and accomplish shared objectives. Their successes (or failures) hinge upon their ability to collaborate effectively. Such interdependencies are fundamental to workforce ecosystems. For example, military organizations encompass a diverse mix of internal and external actors, all of whom rely upon one another to ensure successful outcomes for their missions. In discussing training for contingencies, the U.S. Army’s Clark emphasizes that exercises must include all those who would be involved: “We train as we would fight, and when I say fight, I mean it broadly; we could be fighting a natural disaster. There’s a certain percentage of Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy Reserve who we pull in to conduct the exercise and have contributions from all those parts of our workforce.”

As the commanding general of Fort Jackson, South Carolina, the Army’s largest basic training enterprise, Beagle is also aware of the challenges of orchestrating a large, diverse workforce that includes members of the military, civilian personnel, and contractors. His ecosystem contains wide generational diversity, ranging from baby boomers, who appreciate stability, to members of Generation Z, for whom stability is less essential. “We have to now set a baseline of, ‘Where is that common culture?’” Beagle says. “Our shared belief is the U.S. Army. We trust our mission.”

Challenges and Risks of Workforce Ecosystems

Workforce ecosystems bring challenges as well as benefits. Some of these are internal to an organization, such as cultural barriers, while others are products of the context in which the organization operates, such as legal and regulatory matters. A third set of issues concerns unintended societal effects, such as the potential need for governments to bear the burden in future years if there is an increase in the number of retirees who lack retirement benefits and savings.

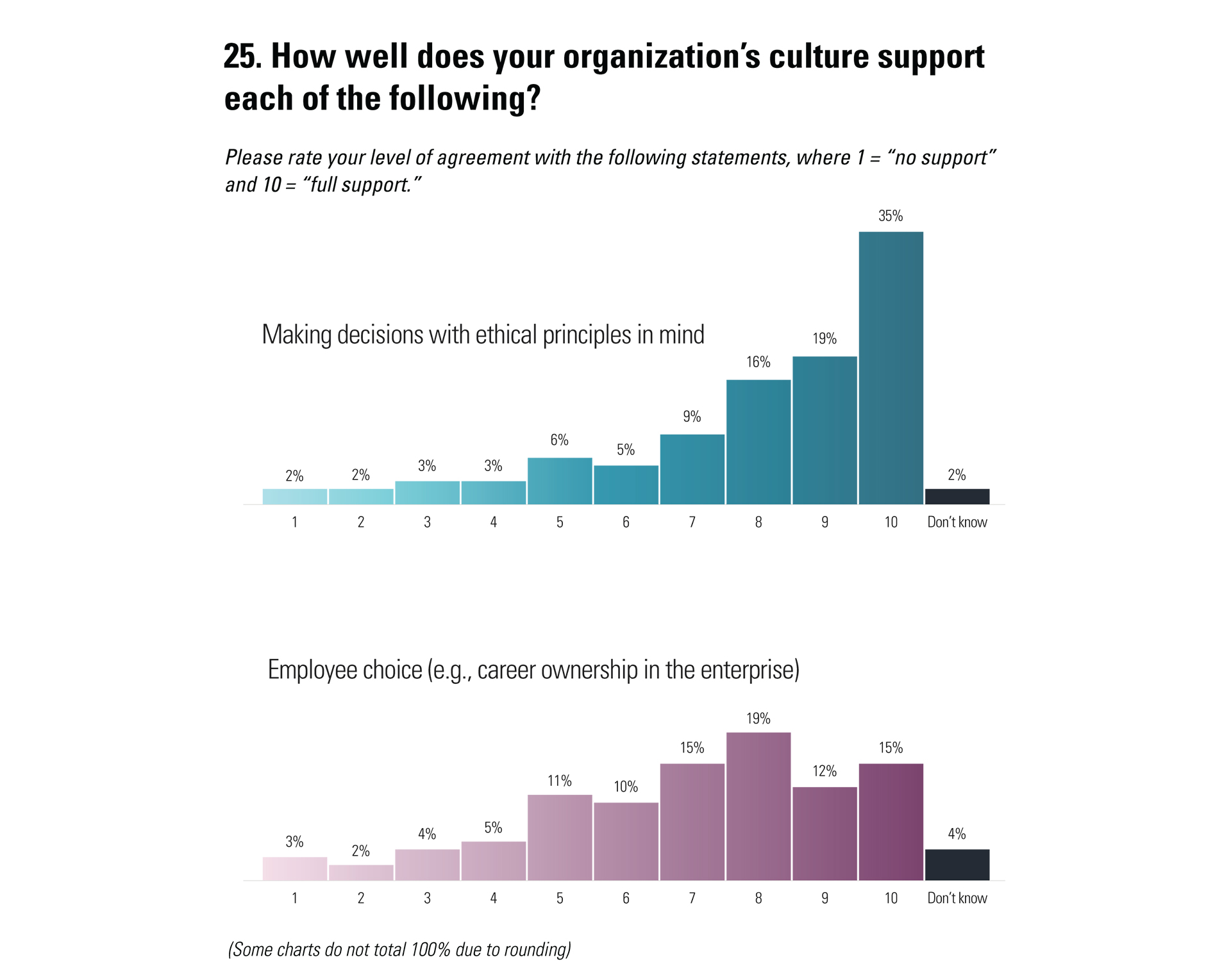

Organizational Culture and Established Practices Can Act as Barriers

Strong internally focused cultures, resistance to change, and organizational silo behaviors can stymie workforce ecosystems. Even before the pandemic, creating and maintaining a consistent organizational culture was difficult, especially in large and highly dispersed organizations. Add remote work, then layer on the challenges of managing an array of external contributors, and cultivating a strong organizational culture becomes even more difficult.

An additional tension for an organization is to be confident and determined in its direction while at the same time being open to new ideas, especially from external contributors. Mayo Clinic’s Mueller notes that advancing his organization’s mission requires openness to new ideas from a variety of players, and that, in turn, requires humility. At the same time, Mayo’s 2030 strategic plan is centered around boldness. Mueller describes a “tension between humility and boldness” that is ultimately productive. Being humble is necessary to accept input from a range of actors, but, he says, it “doesn’t give you license to be passive.”

Oxford’s Corporaal sees cultural barriers to adopting workforce ecosystems, explaining that “often there is little communication between line and staff departments, and with insufficient executive support, this can lead to a lack of budget support to experiment and to do pilots with engaging external talent.” She further recognizes that managers may not understand the value of online labor platforms and can be threatened by the notion of a gig economy — “where internal employees may fear that if they start using these platforms, they will make themselves obsolete.”

Legal and Regulatory Issues Worldwide Present Complex Hurdles

Labor-related legal and regulatory frameworks have been honed over the years to protect employees. The challenge today is ensuring that those regulatory protections remain in place while allowing the growth of new workforce strategies that can extend opportunities and benefits. Companies will need to overcome issues such as HR technologies that are aligned with an employee life cycle approach tracking only internal employees, and geographic, legal, and privacy constraints that prohibit certain types of data from being shared. Regarding Applause’s large crowdsourced community of software testers, Reuveni acknowledges, “Culturally, we treat them like employees. Technically, from a legal perspective, they’re different.”

These regulatory differences pose a familiar challenge for organizations that have a lot invested in how the government classifies workers. In 2018, the California Supreme Court unanimously held that workers must be presumed to be employees, with the burden of proof falling on companies to claim that a worker is an independent contractor. This made drivers for ride-sharing companies eligible for benefits guaranteed to employees by state law. But in 2020, California voters approved Proposition 22, allowing these companies to treat workers as independent contractors. Litigation continued, as a federal court recently ruled to proceed with a class-action lawsuit.

These questions are further complicated in organizations where workforces are dispersed globally, because requirements differ by country. Labor laws in the European Union, for example, provide employee protections, but the EU is currently considering legislation to improve gig worker protections as well. Large organizations often operate in multiple geographies with different approaches to regulating labor markets; workforce ecosystems add to this complexity.

Quality, Brand, and Intellectual Property Represent Vulnerabilities

Pegasystems’ Trefler puts what he calls “the enormous risk'' in stark terms, asking, “How do you maintain quality in a world in which you’re just, in effect, buying slices of somebody’s time?” Susan Tohyama, executive vice president and CHRO at Ceridian, a human capital management software company, points to the risks that may be introduced in using contingent workers. “A company has a product, and you have to have a core team of people who understand that product. Can you augment that team with people who have external expertise? Absolutely,” Tohyama says. “Every company will have a different level — 20%, 40%, 50%. But you have to have a core group of people who truly understand what your product is and what your culture is and make sure that you’re not betraying or straying from that.”

Similarly, Walmart’s Morris points to the reputational risks of using external contributors to fulfill elements of the company’s value proposition: “I might have fulfilled your order and gotten it ready. If I’m using a third party to deliver it and that’s a disaster, you’re not going to care that it’s a third party; you’re going to just care that it’s the company. Regardless of what the alternative forms of a workforce are, because it’s your brand, you have to be responsible from a reputational viewpoint for the delivery of whatever that service is.”

Finally, in traditional employee-centric businesses, ownership of intellectual property is straightforward: The company owns it. When independent contributors simultaneously work for multiple (potentially related or competing) organizations, possibly including their own startups, the question of who has the right to use created property, and on what terms, becomes much more complex. And again, related laws vary by location.

Pay Equity and Parity Reflect Social Justice Issues in Workforce Ecosystems

Adoption of workforce ecosystems may have unintended social justice consequences related to pay equity and parity within organizations and beyond their boundaries. For example, contingent workers may become more vulnerable to exploitation if compensation does not align with that of permanent employees. How should companies define pay equity among internal and external workers? Should they try to do this? What are appropriate metrics across organizational boundaries?

Daniel Rock, an assistant professor of operations, information, and decisions at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, notes that companies do not want “employees internal to the firm to feel uncomfortable when there are multiple layers of treatment. They don’t want tiered systems where internal employees get the benefits of working for the firm and outside contractors don’t. In addition to generating fairness concerns, that creates cognitive dissonance that’s challenging and costly to manage.” Organizations should be careful not to alienate internal employees by treating other workers less favorably.

Another risk is that companies use workforce ecosystems to increase their dependence on external workers in part to avoid paying retirement and other benefits. Workers who neither receive retirement benefits nor save on their own may experience financial disadvantages decades later. The absence of benefits for some worker groups may transfer social safety net responsibilities from businesses to governments.15

Workforce Ecosystems Implications and Takeaways

Adopting a workforce ecosystem has significant implications for a wide range of management activities, including strategy; leadership and culture; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and ecosystem governance. Beyond just being a source of additional resources, these structures provide new ways of organizing and delivering value that can profoundly impact how enterprises operate and deliver value.

Workforce Ecosystems Inspire New Approaches to Strategy

Traditionally, workforce strategy has followed business strategy. With workforce ecosystems, business strategy may follow workforce strategy. Imperial College London’s Christopher Tucci, professor of digital strategy and innovation, describes a “reverse causality,” in which companies “create strategy or influence strategy based on shifting the workforce toward more ecosystem thinking.”

Carmelo Cennamo, professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at Copenhagen Business School, explains, “We tend to see the workforce as a top-down process. We set strategy; we have goals. Then it comes down to operations: ‘We need these resources, and human capital is one. Do we have these people? No, let’s hire them.’ But the other way around — bottom up — will be that the resources you have might actually push you to explore other directions. Some of this pool might be seen as a way to leverage innovation opportunities or strategic directions for the company itself.”

“True competitive differentiation comes from understanding the total workforce,” SAP Fieldglass’s Srinivasan observes. “When I think about business strategy and planning for the future, organizations that are ahead of the curve start with the workforce planning process.”

Tobias Kretschmer, professor of management and head of the Institute for Strategy, Technology, and Organization at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, sketches a scenario in which business strategy might be derived from the workforce ecosystem. “You have access to a much wider range of skills,” he says. “Let’s say I’m a firm that wants to expand to a developing country. If I have temporary workers that have a deep knowledge of this market, I can get them to help me with analysis, with competitor assessment, with market entry strategy. This would have been prohibitively costly before because I would have had to hire someone for that country. To be able to get more fine-grained expertise allows implementation of more fine-grained strategies.”

Our survey highlights organizations’ demand for new skills. An overwhelming majority of respondents — 91% — agree or strongly agree that upcoming changes to their organization’s business strategy require it to improve access to new capabilities, skill sets, and competencies. Accessing new skills through online platforms can produce other benefits, such as insights obtained through the platforms’ data. As Oxford’s Corporaal explains, “First, there is adoption of a platform by a large enterprise to fill immediate hiring needs. But then platforms can also capture things like hiring patterns and seasonality in skills needs. And those are second-order data effects; data is a form of capital that can be leveraged by these platforms.”

Strategy Takeaways

- By encompassing all types of workers in a workforce ecosystem and recognizing the various forms of value that they bring, organizations can develop an integrated workforce view to inform strategic decision-making.

- As part of strategic planning, organizations usually consider how to address workforce needs; with a workforce ecosystem approach, they can choose from an array of mechanisms beyond traditional long-term hiring of employees.

Workforce Ecosystems Call for New Leadership Practices

Workforce ecosystems raise the question of how leaders can create an equitable and inclusive workforce environment across internal and external boundaries. Clark emphasizes the importance of leading all of the diverse actors on a military installation. “Part of it is understanding how to lead everybody, not just the uniformed personnel,” he says. “You have to think about it holistically, and you have to really harness the power that is your entire workforce to be successful. I’ve got to make sure that we’re building an entire team and that it’s inclusive. You have to find a way to build trust within the ecosystem at all levels.”

Companies frequently administer surveys to measure engagement, culture, and other factors. In our research, we found that these surveys often are provided only to employees and not to other worker types, such as contractors and gig workers. Yet, in some cases, these alternative workers may constitute a large percentage of an organization’s workforce. For Clark, the idea of not surveying the total workforce means that “you’re abdicating responsibility to lead the contract personnel — you’re just managing them, which is not good enough.” He adds, “It’s about pulling everybody in. We can’t have people who are not inside the family being treated differently: They’re here. Somebody brought them to the family reunion.”

Leadership Takeaways

- Leaders of workforce ecosystems should recognize and address all types of workers contributing to their ecosystems and engage with all of them.

- Workforce ecosystems, by their nature, are more open and flexible structures, encompassing a diversity of worker types and environments. This may be quite different from an organization’s legacy context and may require new leadership practices.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Considerations in Workforce Ecosystems

Embracing diversity, equity, and inclusion in workforce ecosystems can lead to increased innovation and value creation, along with greater opportunities for fairness and representation. “When we talk about diversity, we’re not just talking about gender, we’re not just talking about race,” says Ingredion’s Adefioye. “We’re talking about experiences. We’re talking about your background and experiences — where you live, where you vacation, the cultures you’ve been exposed to. If you want to have access to the best talent, you have to value and appreciate diversity. With the impact of the pandemic, work can happen anywhere now and, given the disproportionate impact on women in particular and those with caregiver responsibilities, flexibility is key, and people want flexibility.”

NASA’s Skytland adds, “We know from open innovation that no matter how smart you are, the smartest person probably isn’t inside the room with you. That’s why diversity is so valuable.” Walmart’s Morris notes, “If you’re really going to drive creativity and innovation, you have to engage everyone. You have to engage people across the diversity spectrum. Having a diversity angle to what the future of the workforce looks like is really, really important.”

Ceridian conducted a global survey in which it asked employees whether they would be willing to make a lateral move or even take a lesser role in order to gain a new skill set or have a new experience. More than half said they would. “Employees aren’t thinking that they’re chasing titles; they’re chasing experiences,” Tohyama says. “They’re looking for experience equity within their career and not just title equity within their career. Companies are going to have to morph to align with that.”

With a workforce ecosystem approach, managers can rethink geographic boundaries that may have inhibited racial, economic, and other types of equity. At Dell Technologies, chief digital officer and CIO Jen Felch notes that the company has widened its hiring aperture beyond gender and race: “We’re also bringing in people who are neurodiverse, for example, through our Autism Hiring Program, which is designed to provide career readiness training and possible full-time opportunities for individuals on the autism spectrum. We hired more than a dozen new interns in 2020, filling critical positions across cybersecurity, data analytics, software engineering, and artificial intelligence — all while transitioning to a remote working environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. That successful transition showed us that we no longer need to be coupled to a location when it comes to sourcing new talent.”

During the pandemic, WPP made its college internship program a virtual event. “We had hoped that the 300 people we thought would be our interns would sign up to do this 10-week program fully online,” Canney recalls. “We wound up with more than 900, and they were 55% people of color, 71% women, and from 300 universities in 27 countries. It was more diverse than we ever could have imagined.” As a result, the company will likely hire a more diverse group of employees in the coming years.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Takeaways

- A workforce ecosystem approach calls for a reconsideration of what diversity, equity, and inclusion means for your organization and how your workforce policies align with those values.

- Organizations should implement governance and controls to be sure that workforce ecosystem efforts align with social justice initiatives and don’t just enable short-term fixes.

Workforce Ecosystems Present New Governance Opportunities

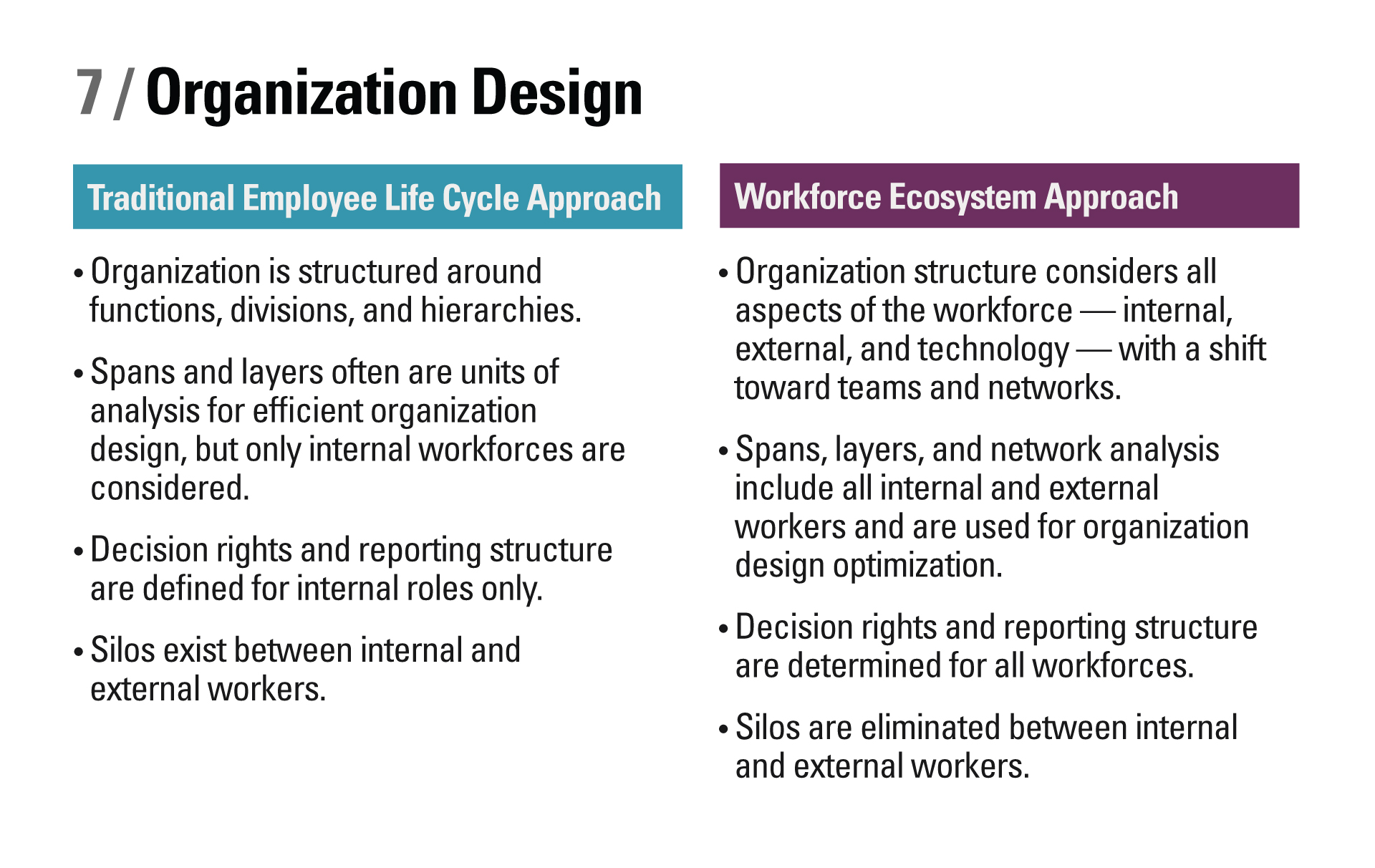

Adopting a workforce ecosystem approach has broad implications for organizational design and governance. “If you’re managing an ecosystem, your organizational design has to be different,” Kretschmer asserts. Traditional organizational designs for an employee-focused workforce typically have separate, unintegrated processes and systems for managing internal and external workers. Responsibility for internal employees rests with HR, while procurement and other departments typically orchestrate external workers.

Shifting to a workforce ecosystem calls for an integrated approach to managing internal and external workers. Our interviews suggest that that shift can be fraught. For many companies, taking responsibility for the contingent workforce means managing risks and the costs of external workers without seeing the benefits of increased productivity. According to interviewees, taking responsibility for external workers is a shared responsibility that crosses functional lines. Nike is recognizing and addressing this challenge. “This is more than just an HR issue — finance, legal, and procurement all have skin in the game,” says Weisz.

Other organizations take a different approach. The management of its contingent workforce was fragmented, so Roche recently brought it under the umbrella of its HR function (now recast as People & Culture). “You have the procurement piece that negotiates the contracts, you have the IT piece that coordinates the access to systems, but there was no one really owning it holistically,” recalls Wilbur. “And when we talked with the other functional areas, there was real support to say, ‘This belongs in People & Culture because it is the whole integrated workforce. We have an opportunity to really understand the capabilities that quite a number of people bring to us that aren’t as deeply established in the current employee base.’” Typically, overall responsibility for workforce strategy rests with the CEO and the CHRO. (See Figure 5.)

Governance Takeaways

- Adopt a cross-functional approach to managing a workforce ecosystem, but also decide who is ultimately responsible. There is no single right approach for all organizations.

- Create a technology infrastructure that can gather and share data and analysis to evaluate what is happening in the workforce ecosystem, whether the ecosystem structure is addressing skills gaps, and how well the ecosystem is accomplishing objectives.

- Ensure that executives with workforce ecosystem governance responsibilities have accountability and incentives related to the performance of the ecosystem.

Rethinking Workforce Management Practices

When the workforce changes from being primarily employee-centric to encompassing a diverse community that crosses an organization’s boundaries, core talent processes must evolve. Most of these processes have been in place for generations and were designed and refined to support a traditional employee life cycle approach. Moving to a workforce ecosystem approach calls for a shift in practices, including making adjustments to underlying philosophies, systems, and processes.

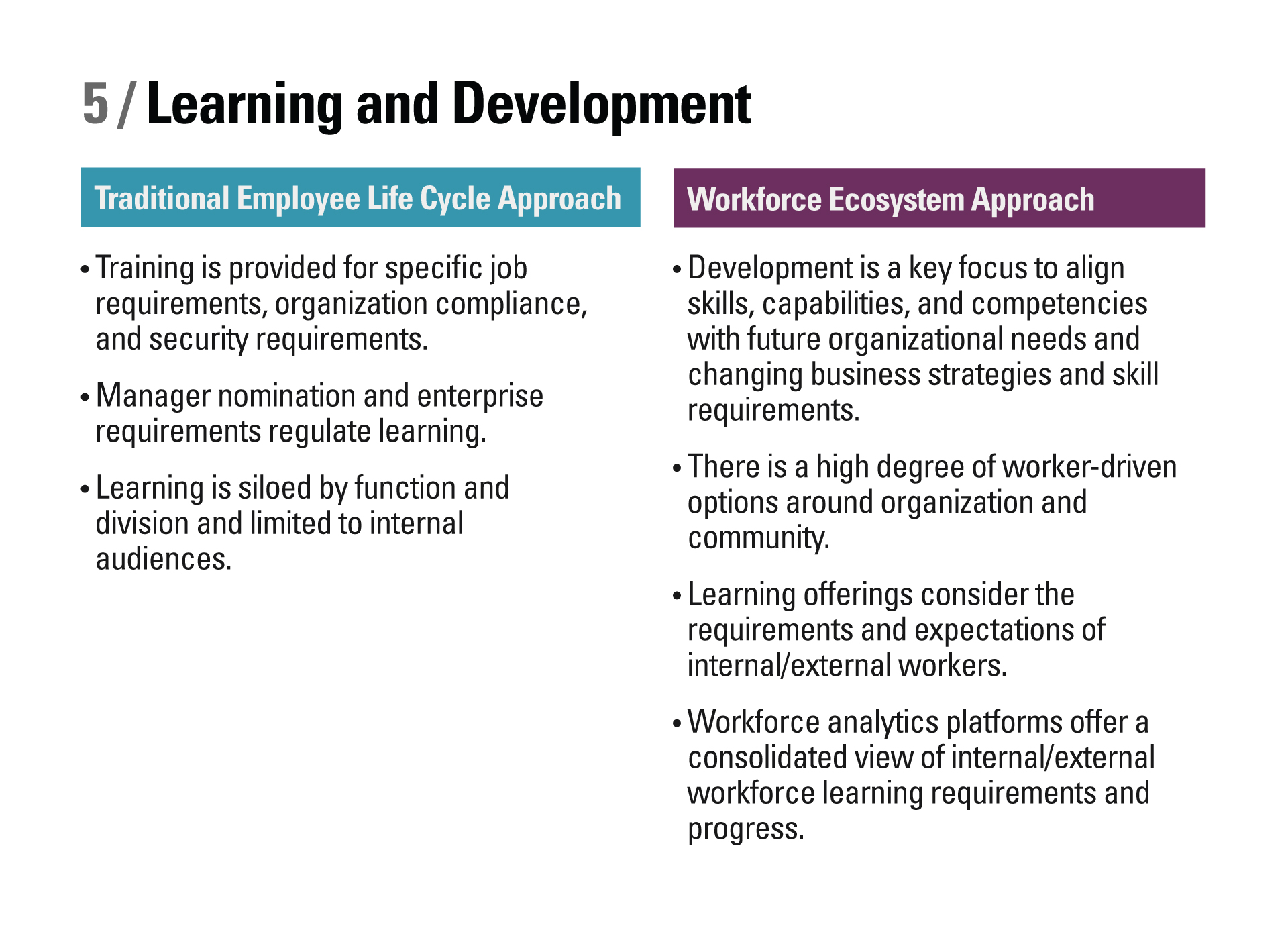

Figure 6 summarizes this shift in terms of differences between the traditional employee life cycle approach and the workforce ecosystem approach across seven areas: workforce planning, talent acquisition, performance management, compensation and rewards, learning and development, career paths, and organization design. For example, the workforce planning process could transition from taking a narrow view of employee roles to adopting a much broader definition that includes both human and digital workforces accessed from a wide range of talent sources. Further, talent acquisition likely changes from a decentralized HR function — which recruits employees independently with minimal coordination across other departments — to an integrated, multifunctional process that spans HR, procurement, IT, and other teams.

Similarly, performance management may move away from annual reviews to become better aligned with ongoing organizational needs. Learning and development efforts should support strategic skills and competencies. Career paths can evolve from traditional latticed structures to encompass both internal and external opportunities through talent marketplaces. Finally, in a workforce ecosystem, organizational structures are more likely to accommodate all aspects of the workforce by shifting toward more team- and network-based approaches. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6: Workforce Ecosystems Call for Shifts in Management Practices

Conclusion

Effectively managing a workforce that comprises internal and external players in a way that is both aligned with an organization’s strategy and consistent with its values is a critical business necessity. However, legacy management practices often remain centered on an increasingly outdated employee-focused view of the workforce. Executives face key choices about how to manage their workforces. They can either continue to manage employees, external workers, complementors, and others through different, often parallel, systems, or they can develop a new, more holistic workforce approach that spans organizational boundaries and different types of workers and contributors. Reframing from an employee-centric approach to a workforce ecosystem approach can drive significant strategic value.

About the Research

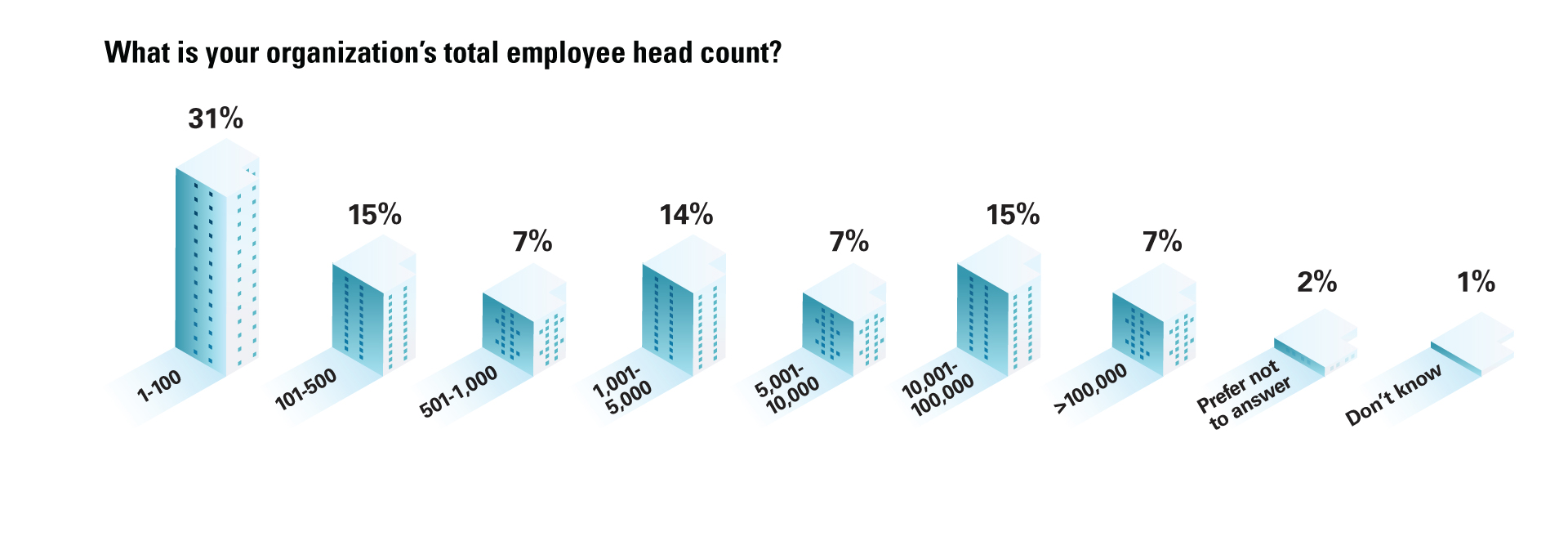

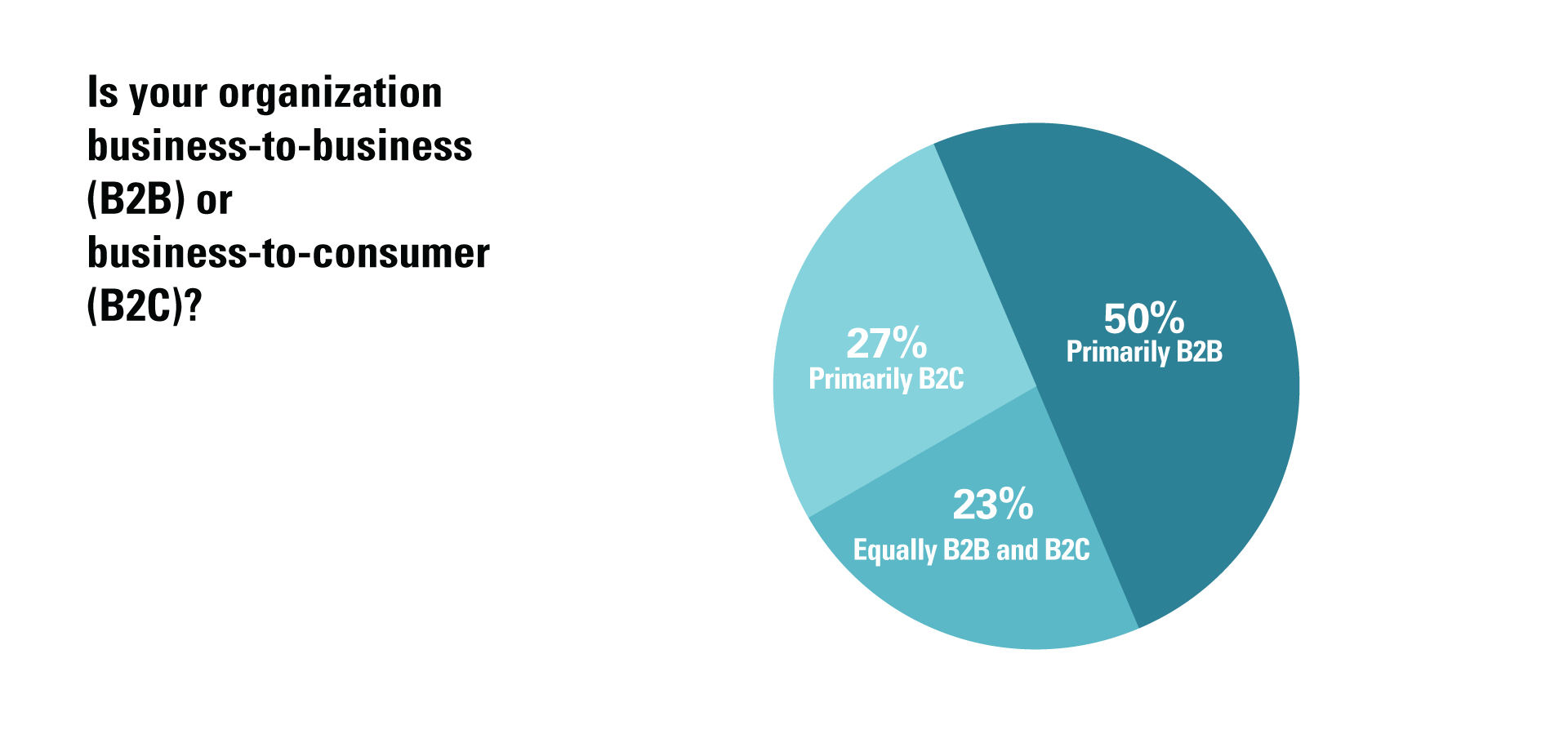

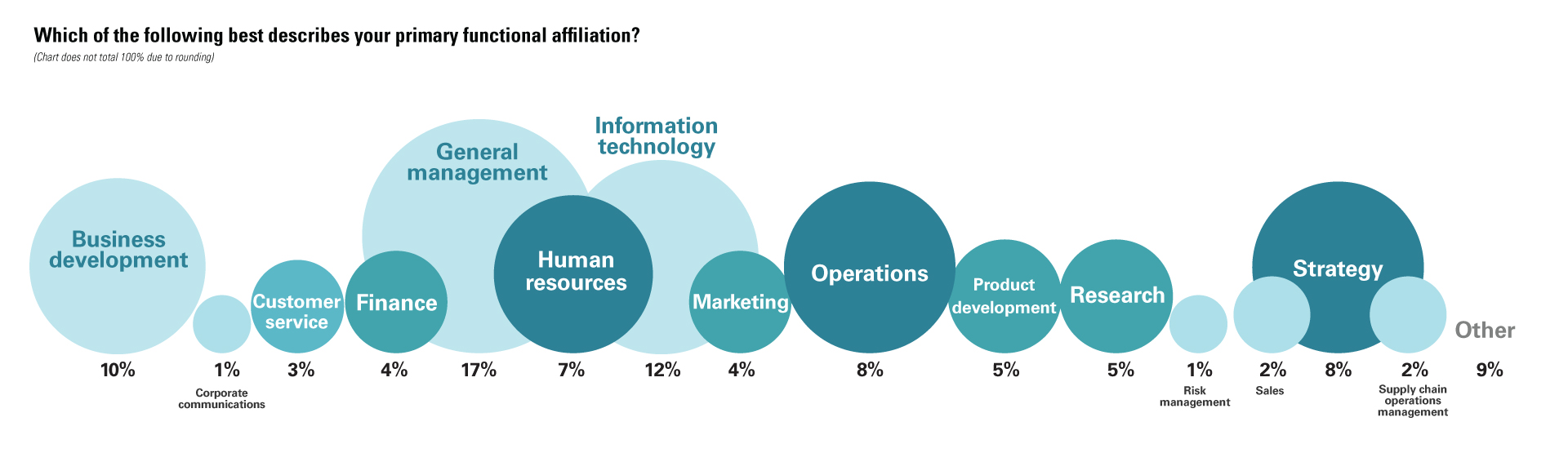

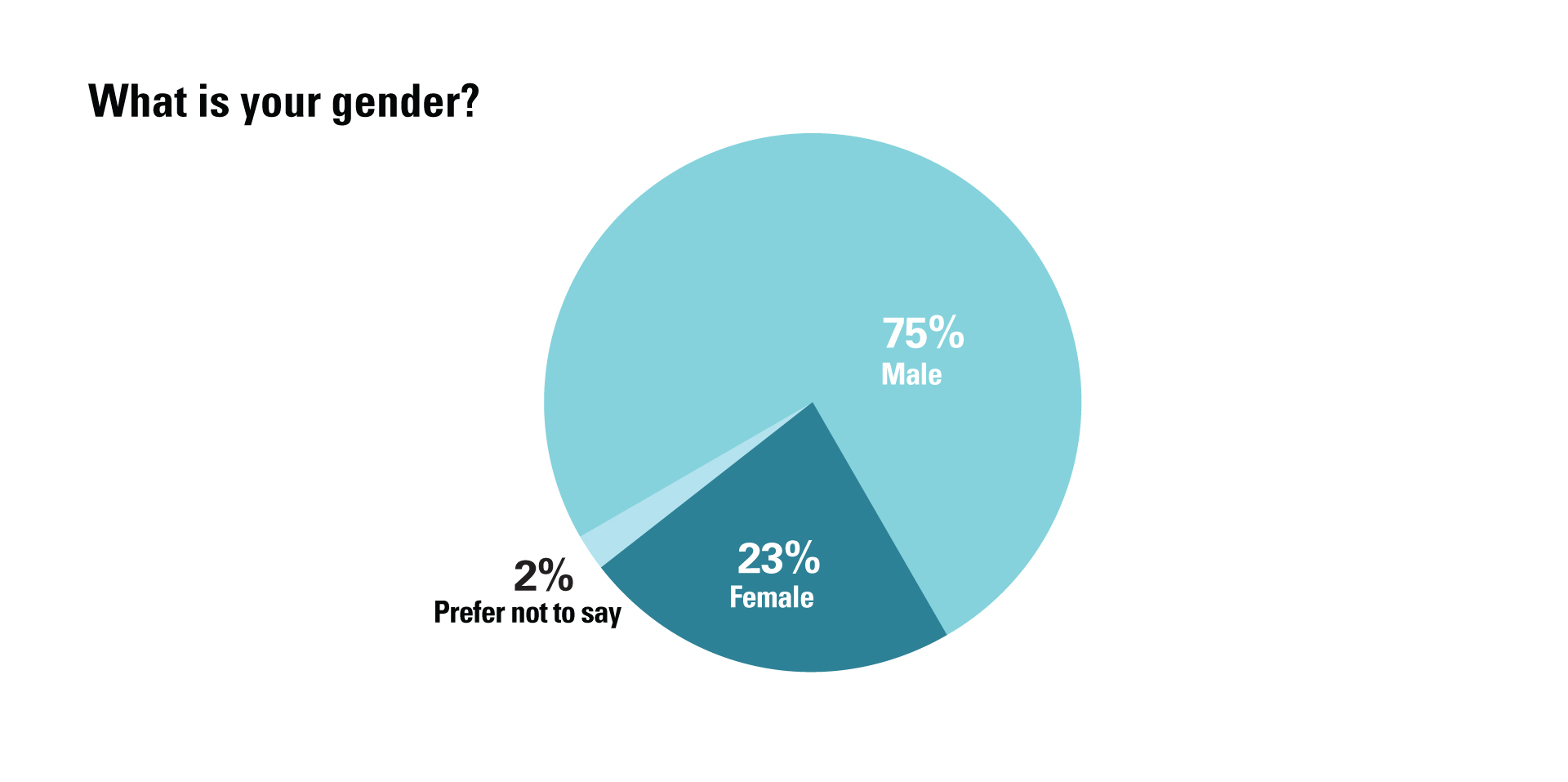

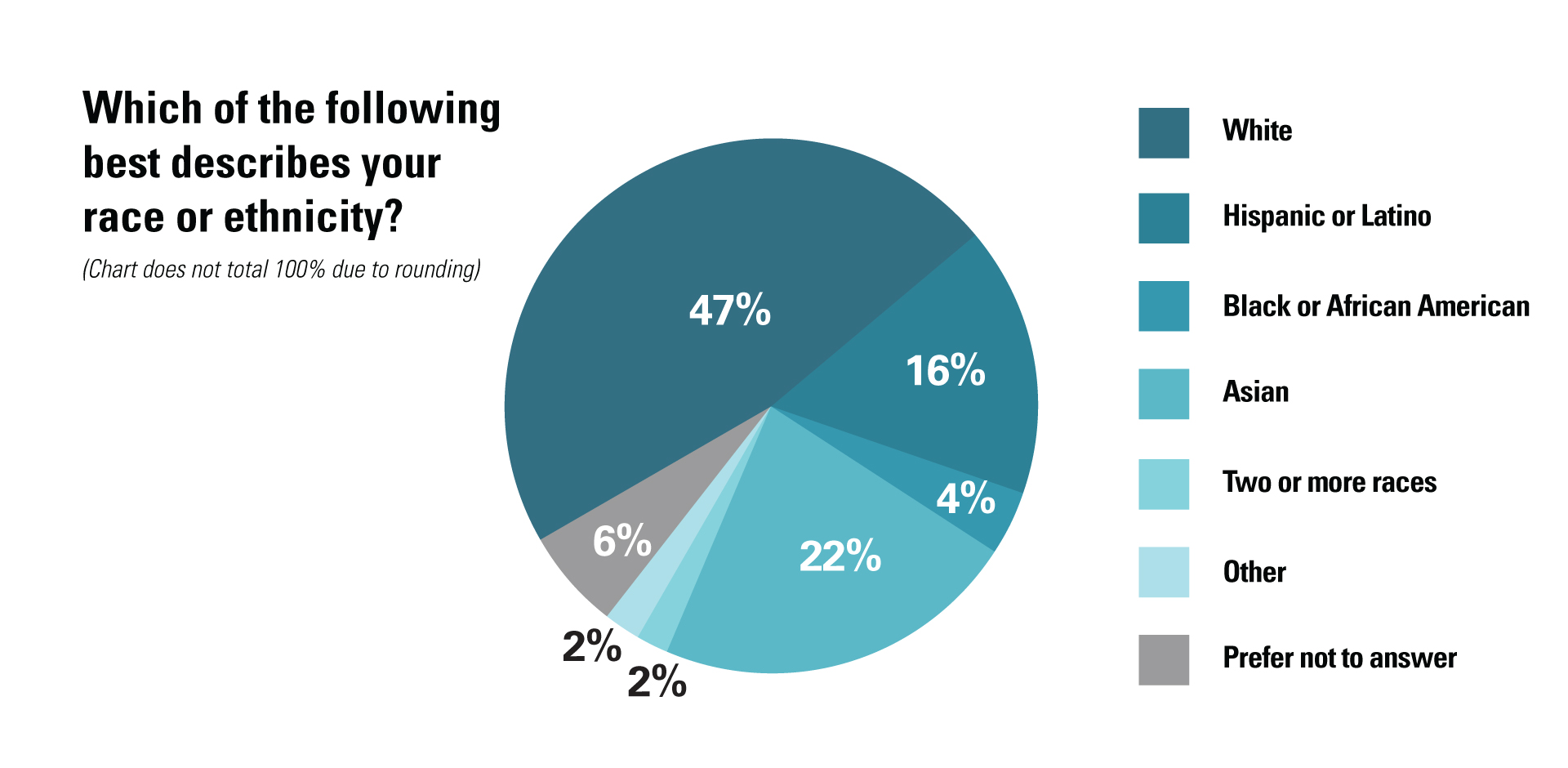

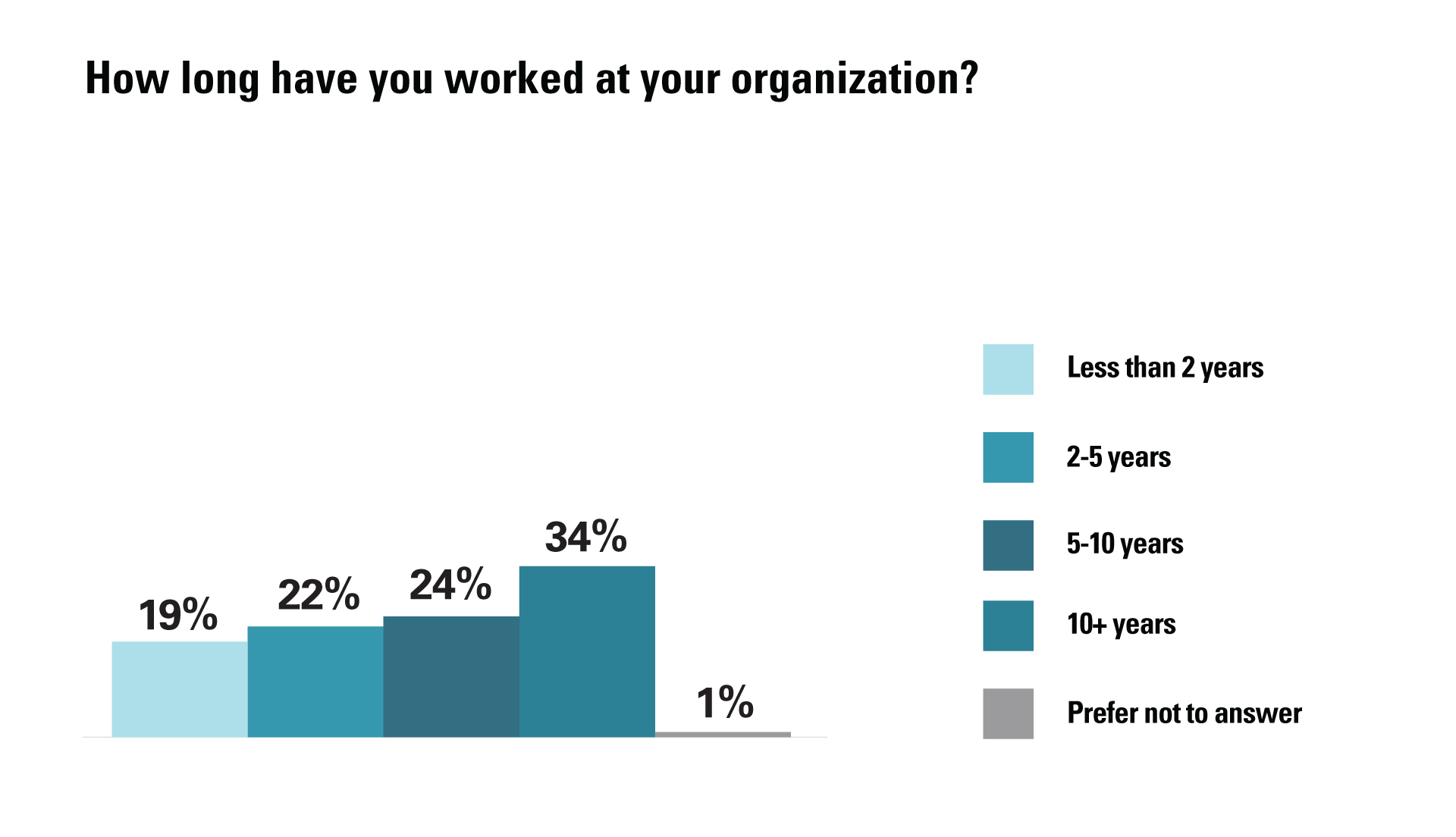

In the fall of 2020, MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte surveyed 5,118 managers and leaders from around the world to better understand how they approach strategic workforce management issues. Respondents represent 138 countries, more than 29 industries, and organizations of various sizes. More than two-thirds of the respondents were from outside the U.S., and over 30% have personally worked in a contingent (nonpermanent) capacity in the past five years. The sample was drawn from a number of sources, including MIT Sloan Management Review readers, Deloitte’s network of executives, and other interested parties.

Additionally, the research team conducted 27 comprehensive interviews of C-suite executives and other senior leaders from private industry, the public sector, higher education, and government to explore topics such as shifts in perceptions related to workforces; links between these shifts and organizational strategy and culture; and implications for management practices. Finally, the team analyzed the management and strategy research literature on ecosystem dynamics, frameworks, and governance structures.

In addition to obtaining the survey results, the team created two workforce definition archetypes based on the responses that reflect which of six categories of workers respondents considered to be part of their workforces. Those who selected full- or part-time employees only were considered to have the most narrow view of the workforce. (See Figure 2.) Those indicating that they considered contributors from all six categories (including gig workers, professional service providers, and developers) to be part of their workforce were considered to have the most broad view of the workforce. Based on this categorization, the team analyzed how the narrow and broad groups responded to the full set of survey questions.

The research for this 2021 report was conducted during the COVID-19 global pandemic, when survey and interview respondents were living through a dramatic shift in workforce practices. Our survey data and interview responses suggest that many trends driving workforce ecosystems were underway before the pandemic began and are likely to continue after the most extreme effects of the pandemic subside. Still, we recognize that some trends were likely accelerated during the time of the research, and others may have been dampened. It remains to be seen what the trajectory of these trends will be in future years.