Profits and the Internet: Seven Misconceptions

Topics

Most managers rightly see profitable growth as essential to their business. However, given the realities of competition and the irreducible uncertainty in business, there will always be a gulf between the pursuit of profitable growth and its achievement. When the Internet arrived, many believed the gulf would narrow. Unfortunately, the opposite has been true.

To be sure, the Internet is powerful. It is opening the way to new markets, customers, products and modes of conducting business. But it also is prompting newcomers and veterans alike unwittingly to embrace some dangerous half-truths and to neglect serious tensions beneath seemingly sensible strategy choices. The consequences are visible in the long list of failed dot-coms. At established companies, the effects might be muted, but if the past is any indicator, they too are susceptible to the penalties of inadequate strategy scrutiny.

In assessing Internet-related business opportunities, companies must not let what is technologically feasible overshadow what is strategically desirable. To minimize any unintentional destruction of value, they must think through the full implications of the strategy choices they are making. In particular, they must be alert to seven widely held misconceptions.

The “First-Mover Advantage” Misconception

A land-grab mentality has pervaded the Internet, not just in startups such as Bluefly, ChateauOnline and QXL.com, but also in established companies such as Microsoft, Telefonica and Reuters. The logic is that one driver of success (if not the key driver) in Internet-related business is being first. That view has merit. Being first can give a company a frontier-pushing aura (as it did for Apple Computer); can generate free publicity and valuable brand recognition (Amazon.com and Yahoo! Inc.); can move companies down proprietary learning curves (Intel); and can provide a bigger opportunity to lock in unattached customers and achieve critical mass (America Online).1

Yet, in Internet business, first-mover status is a precarious perch on which to rest strategy, and managers should not overrate the importance of early entry and the durability of the advantages it might bring. To see why, consider three strains of first-mover advantage.

The Limits of Preemption

The strategic strain of first-mover advantage rests on preemption — the premise that “the early bird gets the worm.” It applies, for example, to airlines’ choices of routes and oil refiners’ capacity decisions. However, preemption works only when two conditions are satisfied.2 First, the opportunity under consideration must be efficiently sized. The company must be big enough for the opportunity, and the opportunity must be big enough for just one company. (Think of the corner grocery store.) Second, the product or service must be simple enough that offerings are hard to differentiate, as is the case with gasoline, airline seats and television-cable service. Otherwise, later entrants can induce buyers to switch by offering better products and service, as is the case in apparel retailing, restaurants and software.

Those two conditions have important implications for Internet businesses. Most opportunities on the Internet are far from meeting the one-company-is-enough criterion. And even in exchanges and Web portals, where that criterion might hold, products and services are far from simple. In fact, there is tremendous scope for differentiation. Just ask QXL.com, the pan-European first mover in Internet auctions. Rival eBay is surpassing QXL even in its home market. Or ask Netscape, whose browsers were abruptly displaced (even on Macintosh computers) by Microsoft’s Internet Explorer. Or PointCast: The first Internet company to deliver free news online, it is now a footnote in history.

The Importance of Being the Best

In the traditional strain, first-mover advantages are based on three sources: the scarcity of key inputs or distribution channels; sustained cost differentials between first entrants and subsequent entrants; and user-trial and -switching costs.3 None of those holds as much sway in Internet business as in traditional business. Consider Yahoo. In the Internet-portal business, neither the scarcity of inputs (information on Web sites), nor cost differentials (to build and maintain search directories), nor user-switching costs are significant issues. Yahoo is not successful because of being a first mover, but because it is a best mover. If users come to favor Lycos or some other portal, Yahoo will replay Apple’s decline. That is true of other business-to-customer companies, including Amazon.com, TheStreet.com and Travelocity. And, higher switching costs excepted, it is true of business-to-business companies such as FreeMarkets, Reuters and SAP.

The Limits to Exploiting the New Rules

The New Economy strain of first-mover advantage relates to the concepts of critical mass and network externalities.4 Critical-mass effects are present when a threshold proportion of actors (the critical mass) has adopted a particular product, technology or market location, and the remaining actors tip to that choice. Network externalities are present when the benefits that accrue to an actor from adopting a particular product, technology or market location increase with the number of others who make the same choice.

Critical mass and network externalities attract attention because they fuel user adoption and lock-in, and can trigger a winner-take-all dynamic. Lock-in might take the form of a coordination trap — it makes sense to switch only if everyone or nearly everyone else switches. It might also take the form of a system-compatibility trap: If users have made related investments in compatible complementary products and services, then switching on the focal item might entail expensive switching on related items as well.5 In either case, the adopted standard prevails even if offers from other companies are objectively better.

This strain of first-mover-advantage theory is compelling to many managers, but they seem to be forgetting one thing. Although the new rules hint at disproportionate gains, it is far from evident that these rules are exploitable. In particular, there is no guarantee that the benefits of user adoption and lock-in will go to the first mover. Consider that Microsoft overcame being a late mover in PC operating systems or that Matsushita beat Sony in VCR formats or that Cirrus prevailed over Citibank in ATM protocols.

There are several reasons that first movers may not win even in the presence of critical mass and network externalities. First, the processes set in motion often take a long time to play out. If the market is insufficiently ordered, the first entrant may be too early.6 Second, when individual companies try either to monopolize or expressly manipulate the standard, potential users (and other producers) likely will resist getting trapped. Finally, a standard might emerge, but not one that is proprietary to any single company. Witness the ubiquity of public standards such as keyboard layouts, cell phones and the wireless Internet. In short, winner-take-all worlds tend to be accidental, not engineered. In that sense, new or not, the rules are not easily exploitable. It is time to stop grabbing the land and start cultivating it.

The “Reach” Misconception

A company’s potential customers often are distributed in heterogeneous rather than homogeneous segments: for example, corporate and retail segments, affluent and economy-minded, professional and lay. And companies have long perceived that the more they can deploy existing activities and resources to pursue new customer segments and extend reach, the more they can grow their revenues and earnings.

With the Internet, the allure of heterogeneity, or reach, has grown even stronger. It is tempting both new and established companies to use their resources (including brand, bandwidth, capabilities and content) to pursue unprecedented numbers and types of customers.7 Reach is the reason that Reuters, a traditional business-to-business player, contemplated a bold gambit to offer retail customers the content and trading services that it provides commercial institutions. It is the reason that WebMD wants to serve you and me and doctors and nurses and pharmacies and hospitals. And why Enron, another traditional B2B player, weighed a venture with Blockbuster that would have leveraged the cable bandwidth Enron sells to businesses so as to sell movies on demand to consumers.

Some such ventures might indeed lead to new profitable growth, but reach is far from an unmixed blessing. The more reach a company attempts, the greater the risk it runs of undermining fit — the coherence with which a company’s activities interconnect and reinforce one another. Fit is essential to a company’s health and future success.8 Digital Equipment Corp., for example, faltered when it sacrificed fit to reach, attempting to make PCs, workstations, minicomputers and mainframes under one roof.

Greater reach might lead to profitable growth, but it must be undertaken in a manner that preserves or reinforces fit. As eBay considers entering the B2B space or as Intel considers entering the B2C space, each must work out the implications of the reach-fit tension to ensure profitable growth.

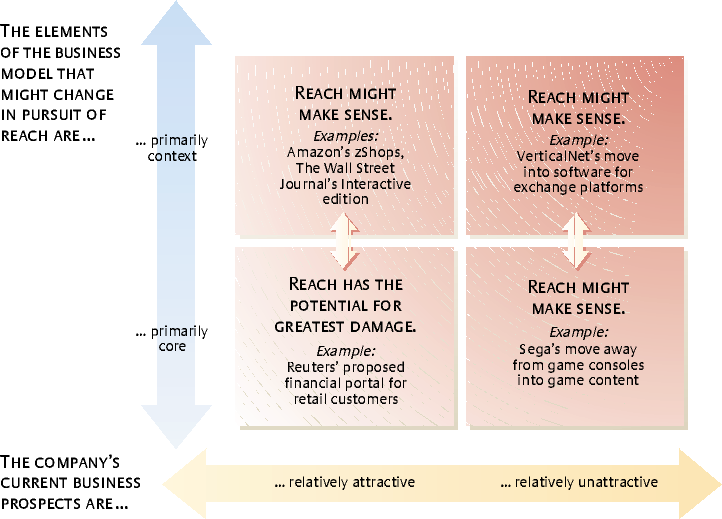

A useful way to evaluate reach opportunities is along the core-context dimension.9 (See “When Reach Makes Sense.”) Core elements and core activities are key to customer value. More important, they drive other elements and activities in the business. Natural-language recognition and search algorithms are core for a site such as Ask Jeeves. A context activity for Ask Jeeves is the design of different interface menus to meet particular customer needs.

Companies in healthy businesses should be wary of reach opportunities that call for changes in core elements or activities. In contrast, changes required to accommodate reach might be fine if they affect only context elements or activities. However, interconnections within established activities may be extensive but not apparent, so companies will seldom find it easy to insulate core activities from changes in context. Moreover, changes in core activities, intentional or not, are hard to reverse.

Amazon.com’s zShops (a network of Amazon-hosted Internet merchants) illustrate how reach can be balanced with fit. The zShop concept does not force Amazon to change its core activities; nor is it hard to reverse. Merck-Medco Managed Care and STMicroelectronics are other examples of companies that successfully balance reach with fit.

If the pursuit of reach means reconfiguring core activities that now cohere well — or making changes in context that will have serious repercussions on the core — beware. Even if the impact would be delayed, companies should resist the temptation. Of course, if the company’s business prospects aren’t that attractive, preserving fit is less of an issue.

The “Customer Solutions” Misconception

Another tempting growth strategy is to provide customer solutions. Here a company goes beyond providing a simple product or service and offers customers access to valuable complements — other products and services that they require to make better use of the core offering.

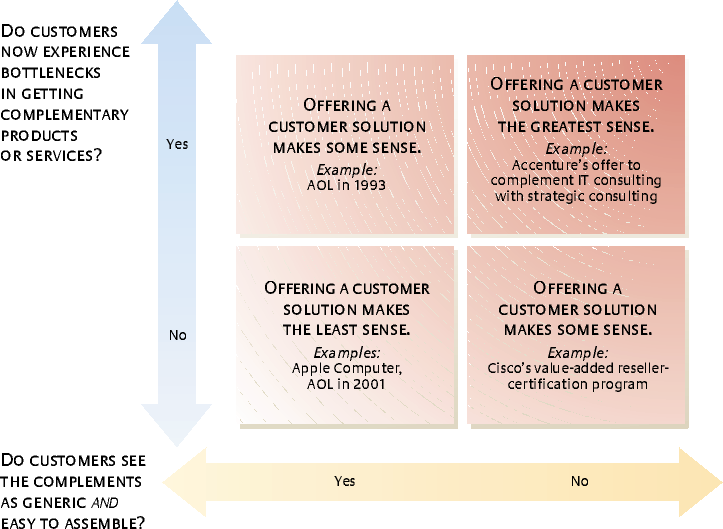

Companies generally offer customer solutions under one of two circumstances. (See “When Offering a Customer Solution Makes Sense.”) First, when a company has acquired a customer for one of its products or services, it might enhance its business by offering complementary products and services to the same customer. The customer gets greater convenience; the company gets greater share of wallet. The extended service warranties that hardware manufacturers offer are a good example. Companies also offer a solution when the complements that customers need are too expensive or are unavailable in sufficient quantities. In that case, without a solution, the company would be unable to sell its core offering to a significant set of customers. Thus Accenture, for example, decided to complement its information-technology consulting services with strategy consulting for senior managers.

As in the reach strategy, however, there is an underlying tension to the customer-solutions strategy that many companies don’t see. This time the tension is between providing a solution and maintaining focus. Focus is about specialization, doing one thing better than anyone else, and it goes to the heart of a company’s business strategy. As Adam Smith noted 200 years ago, specialization can drive both effectiveness and efficiency. When the market is large enough, it pays to specialize. If the market is competitive, it will hurt not to do so. That is why until recently Intel focused on hardware, why Microsoft focuses on software, and why Dell focuses on integration. Apple, on the other hand, tried to do all three. Its aim of providing customers with a convenient solution was noble, but it failed to see the penalty it would pay in both cost and performance.

If companies decide to provide customer solutions internally, they must consider whether potential profits will sufficiently offset any accompanying loss of focus. Companies such as AOL Time Warner, Reuters and Sony are implicitly or explicitly choosing convenience and solutions as their Internet business strategies. If they neglect the tension between providing solutions and maintaining focus, they will pay a price. The diseconomies of scope might be hidden, but they will eventually bring companies down. That point is as important today as it was before the Internet.

Intel, Charles Schwab and Toyota Motor have enjoyed enviable successes. They have asked and answered the question: “What business should we be in?” Then they have worked to be among the best in their business. In a growing Internet-driven global economy, specialization will become more widespread. Generalists that fail to confront the what-business-are-we-in question will find success all the more elusive.

The “Internet Sector” Misconception

Perhaps one reason companies don’t ask hard questions about their business focus is that they view the Internet as an undifferentiated landscape. The B2B and B2C categories are useful shorthand, but they do not help managers identify with the value propositions that ought to underlie their business. Knowing that you operate in, say, the B2B space gives you almost no clue about your company’s raison d’être, customer value drivers, key internal competencies or competitive landscape.

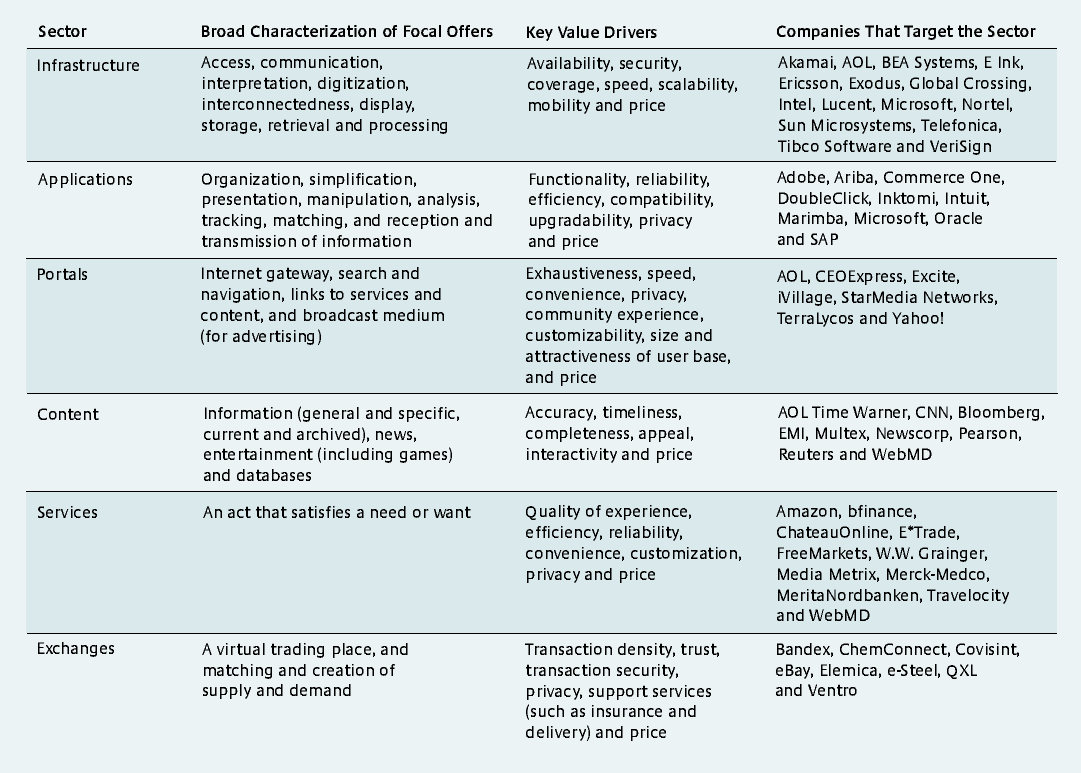

Before it can formulate and evaluate Internet-related strategy, a company must identify the specific Internet sector or sectors in which it is operating. (See “Six Broad Internet Sectors.”) Such identification is critical because three key aspects of competitive advantage are likely to differ across sectors: customer value drivers, performance drivers and the metrics by which each is gauged.

For example, in the services sector, speed, convenience and price might be key value drivers for customers. In the infrastructure sector, availability (24 hours per day, seven days per week), scalability and compatibility might top the list. Similarly, insourcing logistics and keeping a low proportion of fixed costs might be key performance drivers in the services sector, but in the infrastructure sector the performance drivers might be sufficient investment in product design, rigorous testing, and a modular approach to systems and operations. Also, in the services sector, performance and productivity metrics might include brand recall or maintenance cost and transaction value per registered customer. In the infrastructure sector, however, key metrics might include a customer-satisfaction and -retention index, annual billings per customer and profits per employee.

Without developing and tracking sector-specific performance metrics, managers are likely to make poor decisions in allocating resources. That is why industries as varied as consulting, retailing and publishing, to name a few, develop yardsticks suited to the specific nature of their markets and operations. In Internet-related businesses as well, developing sophisticated and sector-specific metrics — beyond Web-page hits and registered users —is essential to formulating and assessing strategy.

There may be more sectors than those we’ve identified. The exact sectors are not as important as realizing that focal offerings in Internet space vary and that customers will have different reasons for selecting them. Settling on a focal industry will help a company decide the depth and breadth of each product or service it wants to offer. It also will help when the company evaluates alternatives and changes to its scope. Failure to decide the company’s core sector may keep it from being best — or invite it to conduct potentially dangerous experiments along the dimensions of reach and customer solutions.

The Misconception of “Best-of-Breed-Partner Leverage”

To resolve the tensions between reach and fit and between solutions and focus, managers are increasingly opting for a partner-leverage strategy — capitalizing on or creating a market opportunity by combining their resources and capabilities with those of other companies. There are many types of partnership arrangements: codevelopment and learning alliances such as those between Philips Electronics and Sony; partnerships to deliver existing products to existing customers more efficiently, such as Covisint (General Motors, Ford and DaimlerChrysler’s online marketplace). The variant that is of interest here is best-of-breed-partner leverage.10

In best-of-breed-partner leverage, a company identifies and works with one or more partner companies, each of which is called on to make a discrete and complementary contribution toward the pursuit of a target opportunity. Thus Palm partners with Nokia to extend its “reach”; and Cisco creates ties with Cap Gemini Ernst & Young and IBM to offer “solutions.” Best-of-breed partnerships may have different goals, such as to extend reach or offer a solution, but they share three characteristics that distinguish them from other partnerships. First, the partners’ roles in creating customer value are stable, and the relationship is expected to be long-term. Second, there is a significant degree of coordination and cospecialization among partners. Finally, no one partner has legal control over any of the others.

Best-of-breed-partner leverage can be a sensible approach, but managers should not elevate it to the status of unambiguous virtue. True, the Internet makes it easier and cheaper to align activities across company boundaries, but it does not do much to align interests across those boundaries. Without aligned interests, joint value creation (let alone joint value appropriation) remains a strategic hope rather than a business reality.11

A more disciplined approach is to balance partner leverage against the less fashionable concept of control.12 Control is what gives top management the right to exercise discretion over how resources will be allocated and which actions to pursue. Control is not that critical when things go well, but when they don’t, as is inevitable at least some of the time, all sides will be clamoring for discretion over strategy. That is one of the main reasons such alliances seldom succeed for long.

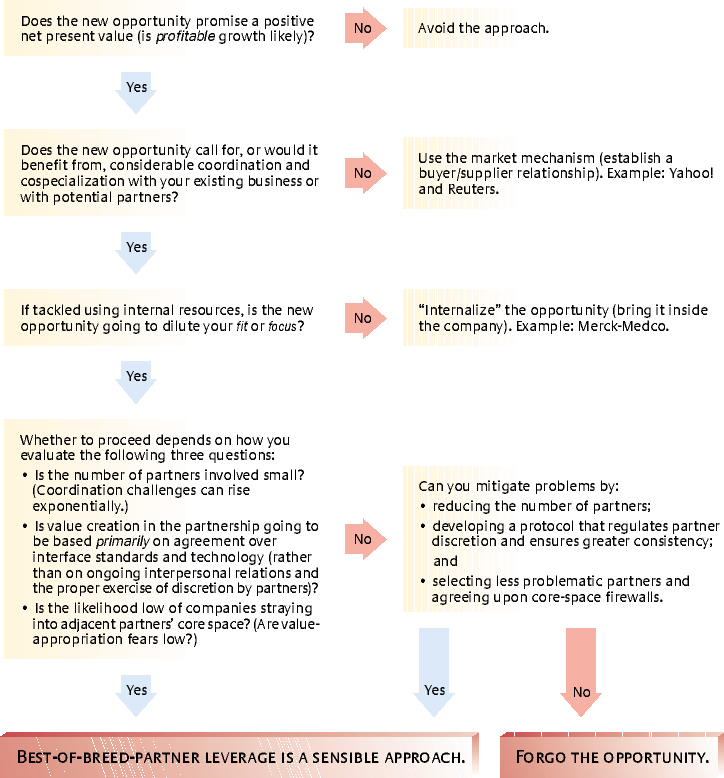

In deciding whether or not to rely on best-of-breed-partner leverage, there is no substitute for good judgment.13 Good judgment, however, ought to be informed by the principles of prudence and process. The principle of prudence argues that partner leverage is worth considering only if the company needs access to an activity or business that otherwise would disrupt its fit or dilute its focus; and if relations with prospective partners are not going to be cumbersome. (See “When Best-of-Breed-Partner Leverage Makes Sense.”)

The principle of process says that when making decisions that will impact all the partners, companies must adhere to the elements of fair process — they must engage, exchange and explain.14 Intentions, actions and volition play a key role in any endeavor, especially one that calls for various entities to cooperate. The track records of eBay, Intel and Nokia, for example, show that it is possible for companies to balance partner leverage with control and use it to achieve profitable growth.15

The “Born Global” Misconception

Seeing an end to border tyranny, many commentators and managers believe that Internet businesses can spread across the globe effortlessly. It’s easy to see why they think that: Bits and bytes travel at the speed of light and at very low cost; Web sites are accessible from anywhere the law and equipment permit.

Unfortunately, that born-global view, although appealing, is a dangerous half-truth. All successful global companies will go to the Internet, but not all Internet companies will be able to go global. To be successful abroad, they will have to learn what MTV, Wal-Mart, Honda and others have discovered: You must first be successful at home, then move outward in a manner that anticipates and genuinely accommodates local differences.

To go global, Internet businesses must overcome at least three hurdles. First, potential customers must know that the company exists. There are so many sites: Surveys by the Internet Software Consortium (http://www.isc.org) reported registered domain names in the tens of millions as of July 2000. Despite the emergence of search robots, a company typically must make a heavy investment in local marketing.

Second, users must trust the company enough to conduct business on its site. Trust increases with local presence. Local management and employees bring local relationships and contacts; local presence allows local media access and scrutiny and enables local legal recourse. All those factors contribute to trust. Contrary to the hyped model of servers in Boston, software in Bangalore and customers in Berlin, dot-coms must establish local sites, country by country — as successful companies such as eBay, Schwab and Yahoo! know well.

Finally, people must want to buy the company’s offering. Unless you’re an Intel, that means more than rolling out home-grown products and services. National borders embody discontinuities, which may include language, currency, income levels, consumer tastes or differences in the regulatory and competitive landscape. The Internet doesn’t eliminate them. Companies must adapt or fail. AOL is an also-ran in nearly all the foreign markets it has entered. Amazon, Priceline and QXL.com also have discovered the myth of the born-global Internet business.

The “Technology-Is-Strategy” Misconception

The misconception that equates technology with strategy is perhaps the most deadly and persistent. Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla states that now “technology is a driver of business strategy” and that, within Old Economy companies, a visionary CIO will be “the key to a company’s success.”16 Geoffrey Moore, another Silicon Valley guru, adds, “In this new age, IT is not about the business — it is the business.”17

Technology has made immeasurable contributions to society and to the success of countless companies. Like electricity 100 years ago, the electronic phenomenon we call “digiticity” is likely to have a profound influence on what, how and for whom companies produce. Yet the fundamentals of economics and strategy have not changed and are not about to. Technology and strategy are strong complements, not substitutes. Companies that understand their technology better than they do their customers and their competition won’t succeed in any economy, old or new. Would Lexus have penetrated the auto industry if Mercedes had thought more about customers than technology? Would AT&T have had to pull out of the credit card business if it had understood customer-credit scoring as well as it understood back-office operations? Then there are the billions that General Motors sank into technology during the 1980s and the costly debacles at Globalstar and Iridium Satellite.

The sooner companies stop confusing what is technologically feasible with what is strategically desirable, the sooner they will realize that a company can achieve and sustain profitable growth only to the extent that it delivers on two strategy fundamentals: product advantage and production advantage.18

Product Advantage

Product advantage is a company’s ability to offer genuine and unusual customer value — in short, to be the best or among the best in class. Amazon, Adobe, Nortel, Nokia, Sony and Schwab have demonstrated product advantage. Such advantage emerges from many sources (including serendipity), but the result always represents a valuable advance on genuine customer problems, needs and aspirations. Thus, product advantages always correspond to demand-side insights, and companies should gauge product advantage against demand-side parameters, such as efficacy, excellence, variety, convenience and speed.

Production Advantage

Product advantage alone is not sufficient for profitable growth, however. Customers — both corporate and retail — operate under budget constraints and perceive value not only in the performance of an offer but also in its price. That is why unit costs play an important role — and why a second strategic fundamental is production advantage.

A company has production advantage when it can extend its offering to customers at prices that the mainstream market deems affordable and that the company deems profitable. Nokia, Microsoft and Intel have production advantage (as demonstrated by their high return on capital), but as yet, most newly launched Internet businesses, including Amazon, E*Trade and Yahoo, do not.

Like product advantage, production advantage can come from many sources. The common aim is to lower total unit costs without diluting product or service quality. Further, once a company achieves those lower costs, it must be able to sustain them. Thus production advantage corresponds to insights on the supply side. However, production advantage must be gauged not only against supply-side parameters (quality-adjusted productivity, throughput, learning-curve coefficients, turnaround times and the like), but also against target-price parameters. The target price should reflect both customers’ willingness to pay and the prices of rival offers.

When observers point to Cisco, Schwab and Exodus Communications as technology leaders, they make an incomplete, if not incorrect, attribution for the success of these companies. Their success is first and foremost rooted in their insightful grasp of customers’ needs, aspirations and constraints. Working from that foundation, they used technology to deliver value in a creative, effective and efficient way.

Asking the Right Questions

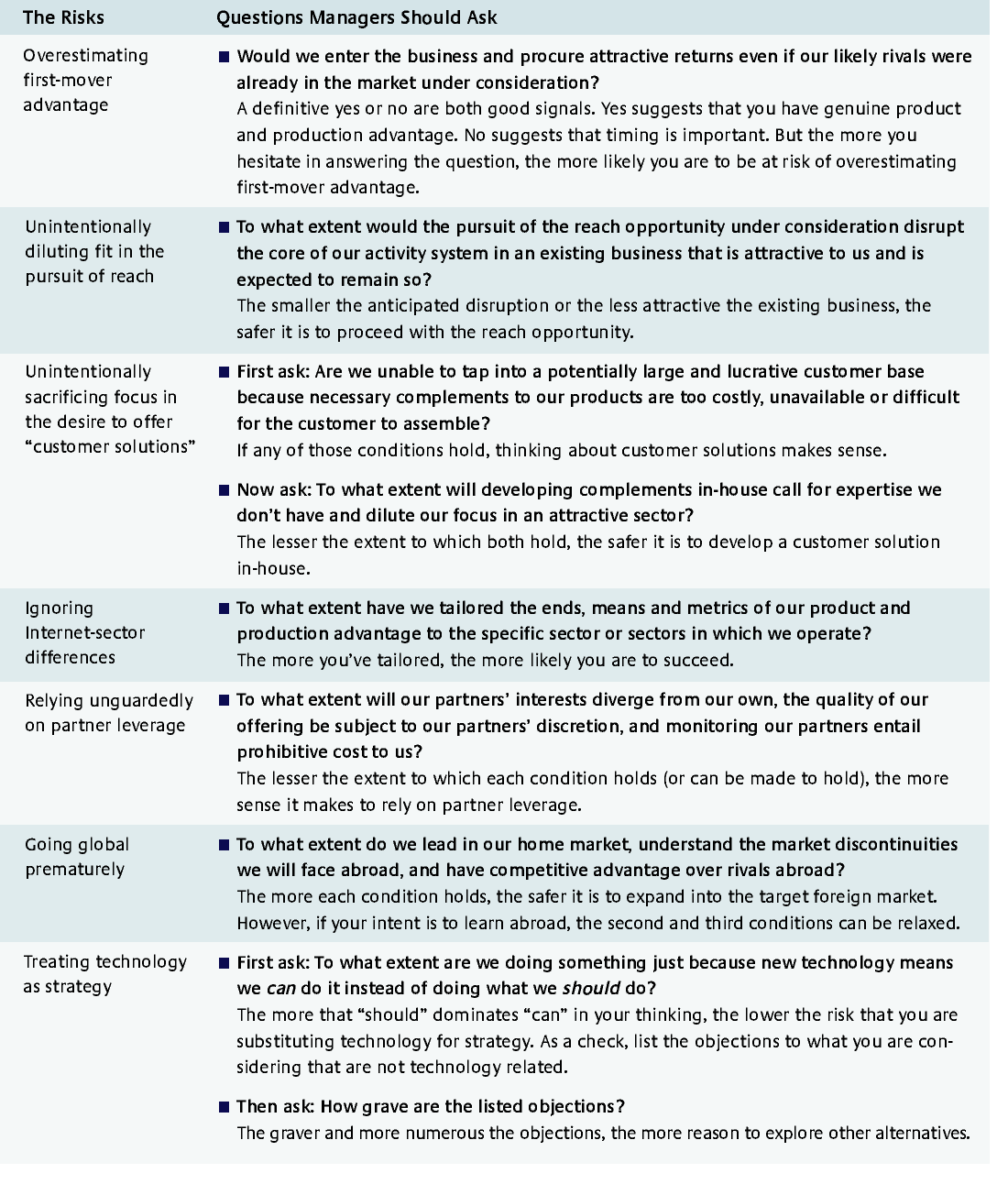

The risk that attends a new and powerful technology like the Internet is that companies selecting growth opportunities let possibility overshadow profitability. The way forward will doubtless be paved with experimentation. But wise managers will shape the bounds and direction of their experiments with good judgment, asking questions about potential strategies rather than hastily embracing popular views.(See “Avoiding the Risks of Internet Misconceptions.”) Because the relative dangers are not the same for Old and New Economy companies — and because the risk will not have the same relevance or severity for all companies at all times — each manager must carefully weigh the importance of each individual risk.

Options emerge from technology, choices from strategy. That is why we have emphasized that although technology and strategy are strong complements, they are not substitutes. To be members of the Profitable Economy, companies must attain both product advantage and production advantage. Although the landscape has changed, the path toward profitable growth has not.

References

1. For a review of several theoretical and empirical studies on this topic, see F.M. Scherer and D. Ross, “Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990), 407, 586–589.

2. M.E. Porter, “Competitive Strategy” (New York: Free Press, 1980), 336–338.

3. M.B. Lieberman and D.B. Montgomery, “First-Mover Advantages,” Strategic Management Journal 9 (September 1988): 41–58; and I. Dierickx and K. Cool, “Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage,” Management Science 35 (December 1989): 1504–1511.

4. C. Shapiro and H.R. Varian, “Information Rules” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998), chapter 7. We have seen no consensus on the distinction between Old and New Economy companies. One way to contrast the two might be to categorize New Economy companies as those operating businesses in which standards tend to matter, product life cycles are relatively short, and network externalities generally hold.

5. G. Saloner, A. Shepard and J. Podolny, “Strategic Management” (New York: John Wiley, 2001), chapter 9.

6. M. Cusumano, Y. Mylonadis and R. Rosenbloom, “Strategic Maneuvering and Mass-Market Dynamics: The Triumph of VHS Over Beta,” Business History Review 66 (spring 1992): 51–94.

7. P. Evans and T.S. Wurster, “Getting Real About Virtual Commerce,” Harvard Business Review 77 (November–December 1999): 85–94.

8. For a full discussion of the concept of fit, see M.E. Porter, “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review 74 (November–December 1996): 61–78; and N. Siggelkow, “Change in the Presence of Fit: The Rise, the Fall and the Renascence of Liz Claiborne,” Academy of Management Journal 44 (August 2001).

9. G.A. Moore, “Living on the Fault Line” (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), chapter 1.

10. For a discussion of competitive leverage (using rivals’ strengths to advantage), see M. Cusumano and D. Yoffie, “Competing on Internet Time” (New York: Free Press, 1998). For a discussion of internal leverage (leveraging core competencies), see G. Hamel and C.K. Prahalad, “Competing for the Future” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1994).

11. For a discussion on the importance of governance in Internet-related business, see N. Venkatraman, “Five Steps to a Dot-Com Strategy: How To Find Your Footing on the Web,” Sloan Management Review 39 (spring 2000): 15–28.

12. O.E. Williamson, “Markets and Hierarchies” (New York: Free Press, 1975), chapter 2.

13. For a discussion of when and how alliance arrangements can play a role in organizing for innovation, see H.W. Chesbrough and D.J. Teece, “When Is Virtual Virtuous?” Harvard Business Review 74 (January–February 1996): 65–73; and Y. Doz and G. Hamel, “Alliance Advantage” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

14. C. Kim and R. Mauborgne, “Fair Process: Managing in the Knowledge Economy,” Harvard Business Review 75 (July–August 1997): 65–75.

15. For a discussion of how companies might deal with this growing challenge, see A. Gawer and M. Cusumano, “Platform Leadership: How Market Leaders Drive Industry Innovation” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, spring 2002).

16. D. Champion and N.G. Carr, “Starting Up in High Gear: An Interview with Venture Capitalist Vinod Khosla,” Harvard Business Review 78 (July–August 2000): 99.

17. Moore, “Living on the Fault Line,” 20.

18. For perspectives on how companies can create customer value and sustain competitive advantage, see C. Kim and R. Mauborgne, “Value Innovation,” Harvard Business Review 75 (January–February 1997): 103–112; and Porter, “What Is Strategy?”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

In recent years, many works have focused on the Internet and its impact on business strategy. Among them, a 2000 McGraw-Hill book, “Net Ready,” by Amir Hartman, John Sifonis and John Kador, offers managers a big-picture view of the possibilities associated with the Internet. It makes the applications concrete by describing the practice at Cisco Systems, where Hartman and Sifonis are executives. “

Finding Sustainable Profitability in Electronic Commerce,” by J.M. de Figueiredo, from the summer 2000 issue of MIT Sloan Management Review, provides an insightful discussion on when and how companies can orient e-commerce strategies for competitive advantage. “

Internet Business Models and Strategies,” by Allan Afuah and Christopher Tucci, published this year by McGraw-Hill, attempts to link Internet technology, business models, the competitive landscape and company performance.

A 2001 Strategic Management Journal article, “Value Creation in e-Business,” by R. Amit and C. Zott, examines the sources of value creation in the business models of 59 U.S. and European businesses. The article explores the business model as a locus of innovation.