How Secure Is the Internet?

Given its increasingly integral role in business and society, the Internet’s security flaws are troubling, to say the least.

For businesses, the Internet continues to represent a tool of great potential in areas as diverse as cost-cutting, collaboration and retailing. But there’s a big, potential problem with the increasing reliance by business on the Internet. A 2005 report submitted to President Bush by the President’s Information Technology Advisory Committee described the problem bluntly: “The information technology [IT] infrastructure of the United States, which is now vital for communication, commerce and control of our physical infrastructure, is highly vulnerable to terrorist and criminal attacks.”

Further Reading

For a sobering assessment of the vulnerabilities of the Internet and related infrastructure, read the 2005 report Cyber Security: A Crisis of Prioritization by the President’s Information Technology Advisory Committee.

According to Tom Leighton, a professor of applied mathematics at MIT as well as co-founder and chief scientist of Akamai Technologies Inc. — a developer of techniques to handle Web interactions based in Cambridge, Massachusetts — the difficulty lies in the very design of the Internet. Leighton, who served on PITAC and chaired its subcommittee on cyber security, explained that the Internet protocols used today were in many cases built on top of the original Internet protocols developed almost 40 years ago. And the security needs of the Internet in those early days — when it was used by only a small number of trusted researchers at places like government labs and a few universities — were very different from those of today’s massive global network. “The [Internet] protocols that were developed then were developed in an environment of trust,” Leighton explained. “There were only a few people using the Internet back then, and they were very knowledgeable and very trustworthy.” Times have changed. “Now we have a situation where we have tremendous adoption and use of the Internet and the Web — with very little security,” states Leighton. This vulnerability, according to him, has implications not only for businesses but also for national security.

Leighton should know about Internet security issues. Akamai operates what is known as a “content delivery network” — in essence a worldwide, decentralized network of servers that hosts Web sites for other organizations and delivers their Web content and applications. For example, if a site using Akamai’s services receives a large spike in traffic, that traffic can be distributed throughout the network of servers so that the site’s operation is not disrupted.

What does Leighton see as some of the big security threats facing the Internet? In addition to the more well-known threats such as viruses and “phishing” (the practice of sending bogus e-mails purportedly representing a business in an attempt to get access to a person’s password and account), Leighton described the following problems:

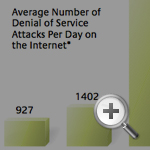

Denial of service attacks. In a “denial of service attack,” a Web site’s IP address is bombarded with traffic in an attempt to overwhelm the infrastructure managing the site. “Bad guys,” Leighton explained, can use armies of “bots”— computers controlled, often unbeknownst to their owners, after having been infected with a virus or worm — to launch denial of service attacks. Such an attack can be targeted at a company or more broadly. For example, InformationWeek reported on February 6, 2007, that on that day a denial of service attack “nearly took down” three of the Internet’s 13 so-called root servers, temporarily slowing the three servers. Though the attack did not have a significant effect on Internet endusers, what would happen if a denial of service attack ever actually succeeded in bringing down all 13 of the Internet’s root servers? Were that ever to occur, it wouldn’t take long before “your browser wouldn’t be able to go anywhere; you wouldn’t be able to send e-mail. Nothing on the Internet would work,” Leighton said.

“Pharming.” “Pharming,” Leighton explained, often exploits a weakness in the DNS, an Internet protocol that allows a “bad guy” to tell a device known as a name server, of which there are millions, that it owns the IP address of an organization such as a financial institution. The hacker will then receive the traffic from that name server meant to go to the financial institution, and the hacker can then send that traffic to a bogus Web page that looks like the financial institution’s own sign-in page. In the process, Leighton explained, criminals can gain password and account information. What’s more, the user may not realize what has happened. Leighton added that another type of “pharming” can use a different Internet protocol, known as the BGP protocol, to siphon off some of the traffic intended for a given site to a bogus site, again in an attempt to gain password and account information.

More troubling still are the larger implications of these techniques if applied against a nation rather than for commercial gain. For example, Leighton noted that one worry is if terrorists could gain account and password information to access critical infrastructure, such as the nation’s utilities system.

What can be done? The PITAC report made a number of recommendations, including increasing federal funding for long-term, fundamental research on cyber security issues. Leighton noted that, if the U.S. government were to fund research to develop more secure protocols to replace those currently used on the Internet, the government could then lead the way by adopting the improved protocols for its own use. That, in turn, would hopefully lead to wider adoption of improved Internet protocols and to a more secure, reliable Internet infrastructure.

“It seems to me that we’re not taking the steps needed to fix the problem,” says Leighton. “But I think it could be done.”