New Greenhouse Gases Regulations Set Stage For Battle

Federal regulations over U.S. companies and their carbon emissions kicked in on January 2. The big question now is how ugly things will get in the coming months.

In a New York Times article last week, reporter John M. Broder wrote that, “With the federal government set to regulate climate-altering gases from factories and power plants for the first time, the Obama administration and the new Congress are headed for a clash that carries substantial risks for both sides. . . . the administration is on notice that if it moves too far and too fast in trying to curtail the ubiquitous gases that are heating the planet it risks a Congressional backlash that could set back the effort for years.”

Broder’s piece gives a concise summary of the state of the climate change political debate. Here are the high points as he lays them out:

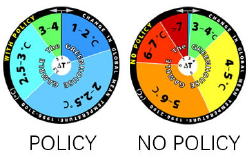

President Obama vowed as a candidate that he would put the United States on a path to addressing climate change by reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas pollutants. He offered Congress wide latitude to pass climate change legislation, but held in reserve the threat of E.P.A. regulation if it failed to act. The deeply polarized Senate’s refusal to enact climate change legislation essentially called his bluff.

With Mr. Obama’s hand forced by the mandates of the Clean Air Act and a 2007 Supreme Court decision, his E.P.A. will impose the first regulation of major stationary sources of greenhouse gases starting Jan. 2.. . . The immediate effect on utilities, refiners and major manufacturers will be small, with the new rules applying only to those planning to build large new facilities or make major modifications to existing plants. The environmental agency estimates that only 400 such facilities will be affected in each of the first few years of the program. Over the next decade, however, the agency plans to regulate virtually all sources of greenhouse gases, imposing efficiency and emissions requirements on nearly every industry and every region.

. . .

Comments (2)

Watson, Robert

Postenprofis.com