Should Your Business Be Less Productive?

In service businesses, increased productivity does not always translate into higher profits. Here’s why.

Topics

Many contemporary businesses are on a quest for productivity gains. They seek to maintain quality and quantity of output at ever-decreasing cost, yielding higher profitability. As advanced economies move more into the service sector, that means many managers devote a lot of attention to designing automated processes that reduce the need for people — typically their most expensive resource.

Sometimes, this works spectacularly well. Alaska Airlines, an innovator in streamlining the passenger experience, deployed a new check-in system at Anchorage International Airport in 2007, called the Airport of the Future project. By 2008, 73% of the airline’s passengers departing from Anchorage checked in via kiosks or the Web, a percentage that was significantly higher than the 50% industry average at the time. That represented a substantial cost savings,1 and the company experienced an 18% improvement in labor productivity. Between 2007 and 2009, Alaska Airlines reduced its work force by 10% and increased its net income by 25%.2

However, not all productivity gains yield such clear victories. Mass media and communications company Comcast Corp. increased its labor productivity by 11.4% from 2006 to 2007, and by another 10.9% from 2007 to 2008. Unfortunately, there were signs that customer satisfaction may have suffered. Comcast may have saved money by increasing its labor productivity, but its customer satisfaction score for subscription television services, as reported by the American Customer Satisfaction Index, fell between 2006 and 2008 and, by 2008, it was substantially below the industry average for that category.

Comcast’s story suggests that in service businesses, productivity gains are not always easy to make without sacrificing perceptions of quality. For service businesses, quality perceptions tend to correlate with investments in labor. The truth is that things are different in service, and unlike on the assembly line, increased productivity may not always lead to increased profitability.

In this article, we propose that in a service business, productivity must be treated as a strategic decision variable, not as a reliable path to greater profitability. We’ll show you the research that explains why productivity improvements often have counterproductive results in a service business. We’ll also explain why managers continue to adopt technologies that alienate their customers. Most importantly, we’ll offer a model for managing productivity strategically rather than optimizing it reflexively. In light of the examples we’ll present — and recalling your own experiences as a frustrated customer — our solution may strike you as obvious. However, as we will show, the belief that productivity increases are always good for any business is a fallacy that is hard to kill.

When Productivity Does Not Lead to Profits

Executives typically think about productivity as something to be maximized; if capitalism were a religion, the virtues of pursuing productivity would be a key tenet. After all, at a macroeconomic level, more productivity always means more profit and ultimately more wealth. If employees do more work than before, how can that be bad? But at a micro level, we believed that the dynamics could be different. To help us understand how service productivity works, we conducted a large-scale study of hundreds of U.S. service companies. (See “About the Research.”)3

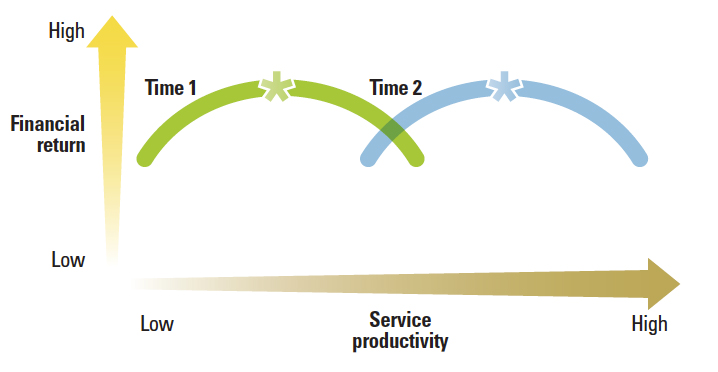

Our model permitted us to test the effect of a number of variables that were predicted by our theory to influence the optimal productivity level. Our analysis showed that for a given level of technology, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between productivity and profitability, implying an optimal level of productivity. (See “The Optimal Level of Productivity.”) Typically, service companies become less profitable if they are either too productive or not productive enough. However, because technology advances over time, the optimal productivity level increases over time.

The Optimal Level of Productivity

For any given level of technology, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between productivity and profitability in a service company. However, as technology advances over time, the optimal level of productivity, noted in each of the curves below with an asterisk, increases.

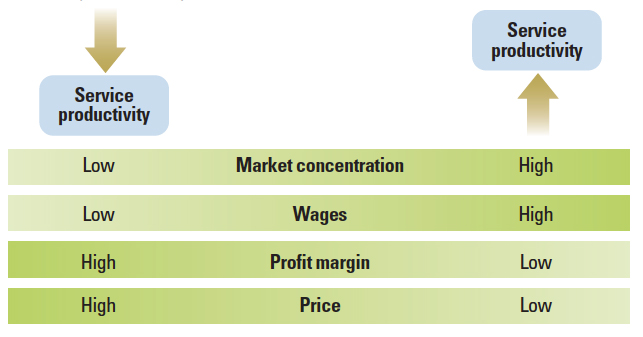

We also found that several factors cause the optimal productivity level to be higher or lower. In general, a higher profit margin and higher price drive a lower optimal productivity level, while fewer competitors and higher wage rates discourage investment in service, encourage productivity investments, and drive a greater optimal productivity level.

The optimal productivity level is not set in stone. As technology advances, the optimal productivity level increases. In fact, we observed that the optimal productivity level increased, on average, by about 20% between 2002 and 2007. An example of this is the evolution of online travel reservation systems. Advances in online technology enabled online travel service Expedia Inc. to increase its productivity by 15% from 2005 to 2010, with no damage to customer satisfaction. Similarly, online tracking in the express delivery business has resulted in increased labor productivity for both United Parcel Service and FedEx Corp., again with no damage to customer satisfaction. In 2003, for example, it cost FedEx $2.40 for a customer service representative to track a package for a customer who called on the phone compared to just four cents to track a package online.4

Managing Productivity as a Strategic Decision Variable

Our research suggests that instead of seeing productivity as an outcome to be maximized, it is better for service companies to view productivity as a strategic decision variable that depends on the business and the technology in question. A company needs to choose the right level of productivity, neither too high nor too low, to maximize its profitability.

Based on our model, the key to making decisions about productivity is considering two factors: (1) the state of the technology and (2) the relative importance of customer satisfaction. In particular, we believe the importance of customer satisfaction is too often underestimated. When customer satisfaction is more important than efficiency, a service company’s optimal productivity level should probably be comparatively lower. Intuitively, this makes sense: Satisfying the customer in a service business is all about anticipating needs, and the greater the number of people available to satisfy those requests, the more satisfied the customer is likely to be.

When should customer satisfaction be given more weight than efficiency? When margins are higher. The Kroger Co. and Whole Foods Market Inc. are both U.S.-based supermarket chains, but Whole Foods, a more upscale food retailer chain based in Austin, Texas, has an incentive to use more labor to serve grocery customers. In other words, the same factors that encourage the provision of better service quality also encourage a lower level of productivity. (See “When to Emphasize Service Productivity.”)

When to Emphasize Service Productivity

When circumstances encourage the provision of better service quality (comparatively high profit margin, high price, low market concentration and low wages), companies should emphasize customer satisfaction more; when the opposite factors are present (high market concentration, high wages, low margin and low price), they can stress service productivity.

On the other hand, there are businesses where, in effect, “your call is not all that important to us.” If the company’s industry is highly concentrated (in other words, there are few competitors) and the customers have fewer alternatives, customer service tends to be less of a priority. Customer satisfaction may be less important, because customers will choose from among fewer competitors. In such a condition, a service company might reduce its labor (increase its productivity) and not worry about losing the customer. With less need to compete, productivity should be higher.

Second, if wages are higher, it becomes more expensive to provide good service. In such a case, the company may wish to automate more, pushing its customers to self-service. Customer satisfaction may suffer somewhat, but the loss of revenue might be made up for by the reduction in costs. So if wages are higher, productivity should be higher.

Figuring out what productivity level to seek can often be facilitated by comparing the company strategically to its competitors. For example, does it have higher prices and/or higher margins than its competitors? If so, this suggests the company should have a lower level of productivity than its competitors. Wage rates can also be analyzed in this way. For example, if a U.S. company is competing against a Chinese company, the U.S. company should probably seek to use less labor (be more productive) than its Chinese counterpart. One of the authors visited a car factory near Guangzhou, China, in the late 1990s, when Chinese wage rates were still very low, and observed Nissan Motor Co. Ltd.’s Altima assembly line. In China, Nissan had an army of workers making each car. In Japan, where wages were high, the car was manufactured almost entirely by robots.

We can get a better intuitive sense of how to manage service productivity by considering “perfect storm” incidences of high productivity and low productivity. Imagine a fast food restaurant in Santa Barbara, California. This is a low-price, low-margin industry located in a wealthy town, where wage rates are high. Zoning restrictions may limit the number of such restaurants, resulting in low competition. Under such conditions, the restaurant should minimize its usage of labor and automate as much as possible. This is the perfect high-productivity situation.

At the other end of the service spectrum, consider an expensive French restaurant in Shanghai, China. Prices and margins are high. At the same time, wages are relatively low and there are many competitors. Under these conditions, the restaurant should use as many employees as it takes to satisfy the customer. In fact, that is often what you see: Visitors from high-wage societies are frequently astonished by the number of service employees in high-end restaurants in cities like Shanghai and Beijing, but they shouldn’t be. That is the perfect low-productivity situation.

Different Companies, Different Solutions

Let us examine several other companies, to see how the model helps us determine whether productivity should be high or low.

- The Kura “revolving sushi” restaurant chain in Japan offers low price and low margin in a high-wage rate environment. Sushi restaurants are numerous in Japan, so competitors abound. Under such conditions, three of the indicators (low price, low margin, high wages) suggest that a high-productivity strategy may be best, and that is exactly Kura’s approach. Kura automates much of the process of making and serving sushi, including involving robots in making sushi; delivering and serving sushi plates by conveyor belts; keeping track of plates by matrix codes; automatically counting finished plates for bill calculation; and cleaning the returned plates. The idea of serving sushi on conveyor belts was not new, but Kura took the appropriate high-productivity strategy to its logical conclusion. As a result of the automation, only a few servers and kitchen staff are needed to serve a 196-seat restaurant.5

- Jetstar Airways Pty. Ltd. is the Qantas budget airline in Asia-Pacific. It is a low-margin, low-price competitor, and aviation regulations typically restrict the number of competitors. These variables (low margin, low price, few competitors) suggest the advisability of a high-productivity strategy. To implement this, Jetstar has adopted a production-oriented high-efficiency strategy; with extensive use of information technology and computation, it attains faster turnaround times and smarter scheduling than competitors. Jetstar has even taken PCs out of airports and operates only on thin clients.6 Everything is designed to increase efficiency and cut costs.

- By contrast, Singapore Airlines Ltd. maintains higher prices and a higher profit margin than its Asian competitor China Eastern Airlines Corp. Ltd. While Singapore Airlines is highly efficient in non-customer-facing operations, it lavishes attention on its customers. All of this gives Singapore Airlines lower productivity than China Eastern Airlines. But the airline routinely wins international service awards, and its advertisements accurately describe itself as “the world’s most awarded airline.”

Toward a New Theory of Service Productivity

Other management scholars have considered similar problems — enough that there is now a large and vibrant movement among some of our colleagues to try to rethink a science of management that was originally forged in the product-dominated world of mass manufacturing. In the manufacturing-dominated economy of 50 years ago, mass production and mass marketing were the name of the game. Quality meant standardization — manufacturing every part the same. Sales were often one-off transactions.

Things have changed dramatically since then. Today every developed economy is predominantly service; for example, the service sector accounts for about 80% of the U.S. economy.7 Information and communications technologies have also made it possible for companies to develop closer relationships with their customers without a huge increase in labor. Yet the same forces driving the expansion of the service sector are also increasing the extent to which service permeates the goods economy.

Increasingly, many goods have become commodities. Only customization, personalization and service produce large profit margins. In fact, much of the goods economy has been offshored to countries with cheap labor. To keep up with this trend, companies like IBM Corp. have transformed themselves from primarily manufacturers to primarily service providers. Nor is Big Blue alone. Many technology companies these days are increasingly service-oriented, and information services is one of the biggest growth areas of the service economy.

A movement known as “service science” has arisen, spearheaded by IBM and other tech giants. In the academic world, this new service science is now being integrated with older, more established thinking about service that began to be developed in the 1970s. The bottom line from both industry and academia is that the shift toward a service economy has transformed the way businesses should be managed. The traditional manufacturing-based, goods-oriented view of the business world no longer works — particularly with respect to how we think about productivity.

Focusing on the Right Goal

The implication is that whether your company is in service or manufacturing, these days, the chances are good that your company is at least partly a service company. If that’s the case, you should reexamine the assumptions about productivity that are embedded in management training and reward systems. In many ways, companies create incentives for managers to increase productivity, even at the expense of revenues and profits. If a manager thinks that he or she will make more money from increasing short-term productivity than from building long-term profits, the company may suffer. (See “The Trouble With Layoffs.”) If you’re an executive, you need to reorient your policies to allow for decisions to be made that compromise productivity to achieve higher long-term returns.

The hard decision to reduce productivity can be made. Consider the implementation of self-serve checkout lanes in supermarkets. Grocers found this technology highly attractive, because they could use fewer workers and increase productivity. Unfortunately, this increase in productivity came at the cost of lower customer satisfaction. According to the Food Marketing Institute, the use of self-checkout in supermarkets reached a peak of 22% in 2007, but it had fallen to 16% by 2010. Grocery shoppers are more satisfied when dealing with a human being. In 2011, Big Y Foods Inc., based in Springfield, Massachusetts, decided to eliminate its self-checkout. Major chains such as Albertsons LLC and Kroger have also removed self-checkout lanes from many of their stores.8 In 2012, when Wal-Mart Stores Inc. expanded its self-checkouts, Whole Foods and Kroger did the opposite: They reconfigured their checkouts with more employees on the premise that using more employees to serve customers was the best way to retain their customers.9

Identifying an Optimal Level of Productivity

How can executives at service companies identify the optimal level of productivity for the organization? Try the following steps.

Compare your company with your competitors.

If your prices and margins are lower, and your employees have higher wages, then a higher productivity strategy is in order. Try to automate more than your competitors. If the opposite is true, focus on providing the best service in your industry, even at the expense of productivity. Where you can get higher satisfaction, use labor where other companies use automation.

Draw a graph, where one axis is customer satisfaction and the other axis is productivity.

Map your company and your competitors on this graph. Consider whether increasing customer satisfaction and sacrificing productivity (or vice versa) might effectively differentiate your company from your competitors, moving your market position away from that of your competition. This could mean adopting more of a high-productivity strategy or more of a high-customer-satisfaction strategy.

Think very carefully before outsourcing services, for example, through offshore call centers.

Seek evidence that the probable decline in customer satisfaction will be offset by increased productivity in labor dollars. If possible, run a test implementation to measure the effect on both customer satisfaction and productivity. Do return on investment analysis on the combined impact of the productivity improvement and customer satisfaction decline, to make sure the outsourcing is justified.

For all major automation decisions involving customer contact, carefully project the impact on customer satisfaction as well as the increase in productivity.

Again, a test implementation, or observing previous implementations by other companies (perhaps in other industries), can provide satisfaction impact data as well as productivity improvement and cost savings. This can enable a fully informed analysis of the resulting productivity-satisfaction trade-off.

Service companies shouldn’t maximize productivity — rather, they should find the most profitable level of productivity. By managing service productivity as a strategic decision variable, a company can balance efficiency with customer satisfaction, enhancing the long-term health and profitability of the company.

References

1. D. Demerjian, “Hustle & Flow,” Fast Company, March 2008.

2. Authors’ analysis of data from the Compustat database.

3. See R.T. Rust and M-H Huang, “Optimizing Service Productivity,” Journal of Marketing 76, no. 2 (March 2012): 47-66.

4. The Economist, “Boosting Productivity: On the Shop Floor,” Sept. 11, 2003.

5. H. Tabuchi, “For Sushi Chain, Conveyor Belts Carry Profit,” New York Times, Dec. 30, 2010.

6. G. Stalk, Jr., “Curveball: Strategies to Fool the Competition,” Harvard Business Review 84, no. 9 (September 2006): 114-122; and B. Winterford, “Q&A: Jetstar CIO Talks Lean IT,” iTnews, June 8, 2010.

7. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment, Hours and Earnings,” 2012, www.bls.gov.

8. A. Knapp, “Humans Are Stealing Robot Jobs at the Supermarket,” Forbes.com, Sept. 28, 2011; and S. Reitz, “Study: Shoppers Prefer Customer Service to Self-Checkout,” Sept. 26, 2011, USAToday.com.

9. “Wal-Mart to Expand Self-Checkout Deployment,” Supermarket News, Nov.1, 2012; and M. Halkias, “Supermarket Checkouts Are Stuck in the Past,” Dallas Morning News, March 3, 2012.

i. For more details about our analysis, see Rust and Huang, “Optimizing Service Productivity.”

ii. See R.T. Rust and M.-H. Huang, “Service Productivity Strategy,” MSI Reports, no. 09-120, 2009.

iii. Newsweek, “The Case Against Layoffs: They Often Backfire,” Feb. 4, 2010.

View Exhibit

View Exhibit View Exhibit

View Exhibit

Comment (1)

Rabindranath Bhattacharya