How an “Abundance Mentality” and a CEO’s Fierce Resolve Kickstarted CSR at Campbell Soup

In his tenure as president and CEO of the Campbell Soup Company, Doug Conant first helped steer the company to financial stability, and then set the stage for aggressive sustainability goals.

Topics

Leading Sustainable Organizations

Douglas R. Conant, former CEO, Campbell Soup Company

During Doug Conant’s ten years as president and CEO of the Campbell Soup Company (he retired last fall), Conant helped refocus the company. In the first half of his tenure, his goal, he says, was to bring the company from being “a poor performing company to being a competitive company to being a good company.” Once that was achieved, about five years in, “we said, ‘we can do better,’ and we started to explore how we could bring what I call our DNA, our natural inclination to corporate social responsibility, to a new level, and kick it up a notch.”

The notion of corporate social responsibility and sustainability has been part of the fabric of the Campbell Soup Company since its inception. The company partners with “fifth generation family farms, to help sustainably advance their agricultural efforts in ways that have been environment friendly as it was understood at the time, for decades,” Conant says. “Most food companies have a ‘reap what you sow” kind of mentality,” and the farmers in the supply chain have their own concerns about making sure their land will be useful in the long term.

In 2006, Campbell Soup began studying what sustainability commitments would mean for the business. In 2008, it recruited a specialist to head up the efforts. And in 2010, Conant set out some “big, hairy, audacious goals” to pursue — like cutting the company’s environmental footprint in half by 2020.

In a Q&A with MIT Sloan Management Review‘s Nina Kruschwitz, Conant talks about his long-time practice of writing 10 to 20 personal notes a day to employees, the power that comes from the “fierce resolve” of the CEO and the “abundance mentality” that allows companies like Campbell Soup to embrace what business author Jim Collins called “the genius of the ‘and’ instead of the tyranny of the ‘or.'”

You say that thinking about sustainability has naturally been part of the Campbell Soup Company’s DNA. But actively pursuing an organized effort takes considerable executive commitment, right?

Yes. In today’s environment, with people getting pushed and pulled in so many different directions, if you really want to get traction with a CSR or sustainability effort, you have to lead from in front. The CEO has to make it a priority. If it doesn’t fall into the priority list, it’s at risk.

When I was there we made it a priority, and it was led by me. I’m the one who created the job for Dave Stangis, our vice president of corporate social responsibility and sustainability at Campbell Soup, to come and do. [See MIT Sloan Management Review‘s interview with Stangis, “Using Creative Tension to Reach Big Goals,” from last fall.] At that point it’s about organizing to execute it in a quality way. You can talk about making it a priority, but if you don’t organize to do it in a priority way, it doesn’t get done. It has to have a line that gets all the way up to the CEO in a compelling way.

What did you do as CEO to lead that effort?

We recruited Dave, we organized to execute, we built a plan and we hold ourselves accountable. We report on it every year. [See the Campbell Soup Company’s 2012 Corporate Social Responsibility Report and its current Sustainability Scorecard.]

I think by doing that, we have built it into the fabric of how we manage the company.

What I was always anxious about was that I never wanted it to be some kind of siloed effort that was incremental to all the other work that we did. I thought it was very important that it be built into how we were making decisions every day. Every decision, you could use a lens on it: How can we do this in a more sustainable and more responsible way?

One of the challenges as a leader is to bring what the late author and business guru Stephen Covey called an “abundance mentality” to the work. We’re talking about doing two things at the same time, creating economic value and social value. People have an appetite to try and tackle that. The places where I see it falling flat are places where the leadership is not actively engaged, and where they employ more of a scarcity mentality — when they say, “what do you want to do, create economic value or social value?” Jim Collins spoke about the “tyranny of the ‘or'” and “the genius of the ‘and'” and I think we put that to work every day at Campbell.

Talk a little bit more about that abundance mentality, which is such a great phrase. You said people have an appetite to create both economic value and social value.

People hunger to be part of an organization that is aspirational. What I have found is that the key to winning in the marketplace is creating a winning workplace, where employees are highly engaged in their work. And by putting this corporate social responsibility lens on all of our conversations at Campbell, people are naturally more engaged. They’re citizens, too, and they care about society. If they can have a choice between creating economic value for the company only, or creating economic value for the company and social value for the community, they’re going to pick the latter every time. We found that as we led from in front on corporate social responsibility, it drove employee engagement. And the more the employees got engaged, the more we advanced our social agenda — and the better we performed.

People spend more of their waking hours either working or thinking about work than anything they do, including being with their loved ones. They want that time to be associated with a worthy endeavor. That’s part of what Covey framed as the abundance mentality. It’s not one or the other, it’s both.

My observation is that increasingly, companies are finding the power of abundance thinking. I find that to be one of the more encouraging trends in the corporate landscape.

When you decided to take this “leading from the front” on sustainability really seriously, did you need to consult anybody? How did it work?

Well, companies go through these cycles, and when I was hired — typically when you hire any CEO from outside — there’s a reason for that, and our company was troubled when I came on. We had lost half of our market value in one year, and we were really struggling to be competitive in the food industry.

So for the first five years I was there, we were really focusing on just getting our house in order, getting the right team in place, and meeting our commitments to go from being a poor performing company to being a competitive company to being a good company.

As we started to get our sea legs and get the fundamentals right, about five years in, we said, “now we can take on more.” If we had tried to take on more earlier with the old management team, it’s not clear to me it would have worked.

We looked at best practices. We secured some resources and partners from outside to help us evaluate how we ought to think about this and approach it. After about a year of study, we figured out what we needed to do. We declared a commitment to it. We went out and hired a leader for it, and then with that leader in place, we started to bring it to life organizationally. In 2010, two years ago, we made this decade commitment that by 2020, we had some big, hairy, audacious goals we were going to pursue, like cutting our environmental footprint in half. We started to operationalize that commitment in 2010.

What do you think are the qualities needed for a good management team for sustainability initiatives?

I think it’s not just for sustainability, it’s for running a company. The simple way to think about it is Jim Collin’s work in Good to Great, but also as it applies to the non-profit world as well. The first thing he says is, before you can make any headway against any major challenge, you have to get the right people on the bus, and they have to be in the right seats. That was our challenge as well. In the first three years I was at Campbell, from 2001 through almost 2005, we turned over 300 of the top 350 leaders.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Stephen Covey, who passed away recently. He was a dear friend, and he used to say, “you can’t talk your way out of something you behaved your way into. You have to behave your way out of it.” And our company had behaved our way into some bad practices, and it took us three years to begin to behave our way out of those practices.

We did that, and in the first three years we went from being totally uncompetitive to competitive in terms of our marketplace presence, our market shares, our earnings and the way we managed the fundamentals of our business. And as we got that bedded down, we were then able to aspire to do more. But to have tried to do more earlier would have been a fool’s errand, in my opinion.

They say a good strategy well executed beats a brilliant strategy poorly executed every time. And we could have come up with a brilliant strategy, but I have no confidence that we would have had the ability to execute it any earlier than we did. Part of the challenge of a leader is to be sensitive and in tune to the capacity of the organization to execute. My judgment was we weren’t ready sooner. I will say that so far, I think we’ve evidenced that we were ready when we did take it on, and it is working.

How would you characterize your role throughout the process?

We stormed through an analysis of the kind of impact we could have. And I say stormed though because it was difficult. We were talking about, “how can we change the world?” Our organization is built on a continuous improvement model which says we’re going to continue to make little changes and eventually they become big changes. This was a different change model.

We said, okay, we want to set some aspirational goals a decade out. And we came up with a big goal in each one of four areas — consumers, neighbors, employees and planet. That took about a year of study and decision making to get anchored in so that the teams owned them and were prepared to act on them.

The full process was managed by our head of CSR, Dave. The teams, which were virtual, reported to my executive team. We had a process where they signed up for these goals, like cutting our environmental footprint in half, even though they didn’t exactly know how they were going to do it. They had enough indicators that it was possible, so they were willing to pursue it. But we had to manage that delicately, because all the study we had done and the lessons learned said, if the organization doesn’t own this, it doesn’t happen.

Were you actively engaged with any of these teams, or did you just hear about things from your executives?

I was engaged in the review process, but I think as a leader the qualities you have to bring to this work are an openness, a humility to realize you don’t have all the answers and a fierce resolve to get it done. And if there’s one thing I did, I was a broken record. I brought a fierce resolve to the work, and this notion of we were going to persevere through the challenges and we were going to find a way. There was no equivocating on this. This determination to find a way and to build a better world, while we were also trying to create economic value for our shareholders: that to me was my primary role.

If I were a lower level employee at Campbell Soup, how would I know that you were saying that? You said you were a broken record.

Well, we would have employee forums every quarter. I had a pulpit in our portal for our Internet. My executive team and I would meet with the four virtual teams that were creating the goals.

So they would hear directly from you?

Yeah, I’d be in the room. And it’s amazing how word travels.

It was also built into the performance expectation process. We had what we called a balance scorecard, where we had expectations of every leader in the company, every individual in the company, that revolved around their role in helping us deliver certain financials, certain marketplace performance and certain key projects. It affected not just their performance evaluation, but their compensation.

So you have to declare it, and you have to hold people accountable for it. You have to review performance, and you have to do it with this kind of fierce resolve that lets the organization know that you’re serious.

Throughout that whole process, what surprised you in a positive way?

What surprised me in a positive way was that I thought this was going to be a harder sell, because everybody has so much work to do. The average employees get what, 200 emails a day? I thought they’d think, “And my God, you want us to do this, too? Isn’t it hard enough to win against our peer group, and now you want to build a better world? Give me a break.”

So I was prepared for resistance, but what was so gratifying is that this was stuff people wanted to work on. They wanted to go home and say, “hey, honey, guess what? We’re building a 60 acre solar field in Napoleons, Ohio, that’s going to be a state of the art facility for harvesting energy from the sun.”

Did you see or hear any of that directly?

Oh, yeah, I would get notes on it from employees. I had a couple practices at Campbell that are relevant to this conversation. One is I would write personal notes to people, and I would write about ten to twenty a day.

Ten to twenty personal notes a day! How did you choose who to write to?

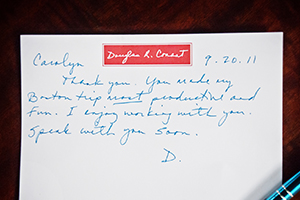

Conant actively engaged staff in CSR with his practice of writing ten to twenty personal notes to employees every day.

Well, I had access to our portal and I would see all the things going right in the company. With the aid of a staff member, I would pick about ten to twenty things every day and I would hand write a note to the person saying, “Thanks for your help on the solar field in Napoleon, Ohio. I understand we’re ahead of schedule. Nice job.” It wasn’t just on CSR issues, but it included CSR initiatives. Over the course of my career I sent out about 30,000 personal notes, and we only had 20,000 employees.

So I was personally connecting with them, and as I would send notes to them, it created a platform where they would send notes back to me. We sort of naturally had this unique dialogue that could be hand written or via email, where employees would start sending me things, like “I think this is a cool idea. Couldn’t we look at a solar field in our facility?”

Another way was, I practiced management by walking around. Inevitably, every day, I would have a half an hour or an hour free, where a meeting would end early or be changed. And whatever time that was, I’d go in my office, I’d put on my walking shoes and pedometer and I’d go walk around our complex. And people would talk to me. I’d bump into somebody in our R&D kitchens who were working on a healthier version of a particular product, where we were trying to reduce sodium in one of our soups or something, and we’d start talking about that, which was one of our big consumer efforts. And before you knew it, I’d be plugged into what was going on with the sodium reduction effort, and they would know that I was interested in it.

This is not rocket science. Tom Peters wrote about it in In Search of Excellence about 25 years ago, that management, by wandering around, helped learn what was going on. But it also signaled to people that I was paying attention. And if I was having a conversation around some CSR initiative with somebody, they would tend to tell somebody else.

I guess the third area that really brought it to life for our employees is I started to talk about it more boldly publicly. I find if you want to get an organization to pay attention, start telling people externally that you’re going to do something. Dave Stangis started getting out more publicly, and I did, and we were signaling to the organization that this was here to stay.

So between my notes, my walking around and my public speaking agenda, I think we brought it to life for employees in a very out-in-front kind of way.

Tell us more about that solar energy field.

That’s a project around our energy usage. When we’re making soup, we use a lot of energy. And our supply chain was running out of ways to re-imagine how the company can continue to reduce its reliance on traditional energy sources in a responsible way and still meet the demands of our soup business. We said, “We can’t think about this incrementally any more. We have to think about this differently if we want to get there.” We started to re-imagine what our other choices of energy were, and chose to lean into solar.

We earnestly investigated the potential of leveraging solar energy more completely. We built what was at the time the largest solar energy field in the United States. It’s 60 acres of solar panels in Napoleon, Ohio, to help meet the energy needs of our plant.

Now we have a glide path over the decade that we can envision tremendously significant reductions in our cost of energy, so that will allow us to be more cost effective with our products, while also using less of our natural resources.

That’s pretty powerful. Can you name any other companies you think are heading in this direction?

Oh, gosh, pick one. Coca Cola is trying to create as much water resource as they are using water. Nestle has got an amazing agenda on social responsibility. Even Goldman Sachs, which has been vilified 18 ways from Sunday, is pursuing more responsible initiatives, like their 10,000 Women program, their 10,000 Entrepreneurs program.

I’m the chairman of the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy in New York, which is an organization founded by Paul Newman and a few luminaries, and we’re exposed to 180 of the Fortune 500 companies and what they’re doing. And it’s awesome what’s going on. Things are going on everywhere, from Newman’s Own to Bloomberg to Carlson companies to General Mills.

People are seeing that as they lean into helping to build a better world, their employees are naturally going to lean in to the corporate agenda a little more. It can be a win/win deal.

Comments (3)

John McCormack

Scott Gemmill

Diana Rivenburgh