Competitive Pressure Systems: Mapping and Managing Multimarket Contact

Topics

Recent research on multimarket contact — the partial overlap of two firms’ geographic or product markets — has stimulated new thinking about how and why firms put pressure on each other.1 Not surprisingly, overlaps put pressure on competitors and escalate the rivalry between firms in chess-like matches for control.2 But under certain conditions, overlapping markets can also create reciprocal threats that cause firms to reduce their rival-rous behavior.3 By exchanging footholds (moderate market share positions) in one another’s important markets, two firms can create “mutual forbearance” — a lesser propensity to attack each other with aggressive price, advertising or innovation wars for fear of damaging counterattacks in other important markets — and a greater inclination to seek growth in nonoverlapping markets.4

Most firms don’t do a good job of managing, through competitor and market selection, the pressure they experience. All organizations sense pressure intuitively, but it is often difficult to see the overall pressure system — a complex, shifting pattern of overlapping contacts among rivals that continually alters the climate of an industry by changing the incentives for players to compete, mutually forbear or even formally cooperate. Fortunately, these systems can be mapped and, unlike weather pressure systems, controlled to a significant extent if they are understood well enough.

Typically, the competitive pressure within an industry is thought of as a continuum, running from hypercompetition to collusion. An industry’s competitiveness is traditionally measured by antitrust experts using an industry’s concentration ratio or Herfindahl index, both based on the distribution of the market shares of firms within the industry. But recent multimarket research indicates that competitive pressure is more complicated than that. Overlaps between different pairs of competitors vary widely, reducing or escalating rivalry differently. And pressure is “asymmetrical”— that is, the pressure firm A places on firm B does not necessarily equal the pressure that firm B puts on firm A, because their overlapping markets may differ in importance to each one’s portfolio.5 Each firm in a system is uniquely affected. Some are targets, whereas others are aggressors or orchestrators of the overall pattern of pressure. Still others are isolated from the brunt of pressure. With all the possible combinations of overlaps that can exist between numerous rivals, no two pressure systems are exactly alike, even if the traditional measures of industry competitiveness are identical. (See “About the Research.”)

As difficult as it is, it is vitally important for an organization to understand its industry’s pressure system. Otherwise it can find itself the industry’s lightning rod, attracting attacks from all quarters. It obviously can’t avoid competitive pressure by cooperating with every competitor in all markets: That’s illegal. Nor can it put pressure on every competitor everywhere: That’s suicide. Managers must understand how to use competitive pressure to create an optimum combination of competition and cooperation among selected rivals.

Unfortunately, managers almost always lack objective measurements and useful pictures of the pressure patterns they face. Typically, strategists see competitive pressure as being based on five forces: buyer power, supplier power, barriers to entry, threats posed by substitute products and intraindustry rivalry.6 Measurement of intraindustry rivalry has been proxied by factors affecting the degree of price competition in a market, such as the number and concentration of competitors, the rate of growth in demand, the industry’s capital intensity and fixed costs, the lack of differentiation, switching costs, the diversity of strategic groups within the industry and the magnitude of exit barriers.7 However, none of these factors explicitly accounts for the complexities presented by recent multimarket contact research nor for the variety of pressure patterns that comprise and influence intraindustry rivalry.

A map based on measured pressures is essential to answering questions vital to the dynamic stability of an industry and the profitability of firms in it. It has important implications for an organization’s market and competitor selection, growth plans, product portfolio and diversification strategy, resource allocation priorities, competitive intelligence system, merger and acquisition strategy, and scenario planning process.

An overall picture of an industry’s pressure system can allow managers to proactively and intelligently decide whether to counter the pressure of a rival or let another competitor do it. Organizations can apply pressure to mold the strategies of others and even to create “win-win” situations in which both rivals advance or protect their positions. They can tailor their selection of markets or competitors in ways that legally redirect pressure, create mutual forbearance or encourage indirect competition. They can avoid entering “attractive” growth markets that will bring on intense retaliatory pressure from unexpected quarters. When used moderately, these tactics can prevent an industry from becoming a pressure cooker. Or they can heat things up when opportunities for capturing or holding industry leadership arise.

For any organization, measuring and mapping the invisible pattern of competitive pressure among its rivals is the first step in creating order out of the confusion that is destroying the profitability of many highly competitive industries.8 Because of frequent internal destabilizing actions and occasional external shocks, pressure systems can never be frozen. The best that can be achieved is a kind of dynamic stability. Companies must seek superior position when possible and avoid intolerable pressure when necessary — but it is most valuable to gain superior strategic influence over the evolution of the system. This results from superior knowledge plus the resources and intent to carry out a coherent competitive pressure strategy.

Pressure System Mapping

The more two firms’ product or geographic markets overlap, the more pressure they exert on each other. The pressure is proportional to the importance of markets to each firm and the degree of penetration by each firm.9 This simple concept enables organizations to quantify the degree of pressure that one rival puts on another. (See “Pressure Measurement.”)

When measuring and mapping competitive pressure, it is not easy to define, on an a priori basis, the boundaries of or key players in an industry. It is best to do this empirically by beginning with all competitors whose markets overlap significantly with the focal firm (the one creating the map) and then including firms that pressure those competitors. The primary purpose of pressure mapping is not to illustrate the current use of competitive tactics (i.e., price, advertising or innovation wars) but to provide insight about who has the potential and the incentive to make or avoid future use of pressure. By casting the net wide, it is possible to find tacit allies and to identify potential acquisitions or opportunities to enter new markets that could shift the balance and direction of pressure applied to selected rivals.

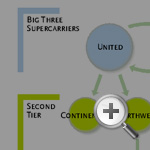

Once relevant rivals are identified and competitive pressures are quantified, they are mapped with symbols. Companies are represented by circles, tacit or formal alliances by lines connecting them, and pressure by arrows showing its direction. Thick, solid arrows indicate strong pressure, and thin or dotted arrows indicate milder pressure. Relative circle size represents the relative size of firms. The mapping is based on hard market share and revenue data that are often readily available in marketing, competitive intelligence or strategic planning groups.

An initial pressure map is apt to be dauntingly complex, a formless array of sources and targets of pressure with a spaghetti-like tangle of lines and arrows connecting them. It is often useful to locate the most focal firm or the most aggressive or targeted rival at the center of the map, or to place the industry leaders at the top of the map to minimize the number of intersecting arrows. Omission of low-pressure relationships and inconsequential rivals can simplify the map to show only key relationships that yield clear insights.

Analyzing Pressure Systems: A Look at the Early 1990s Airline Industry

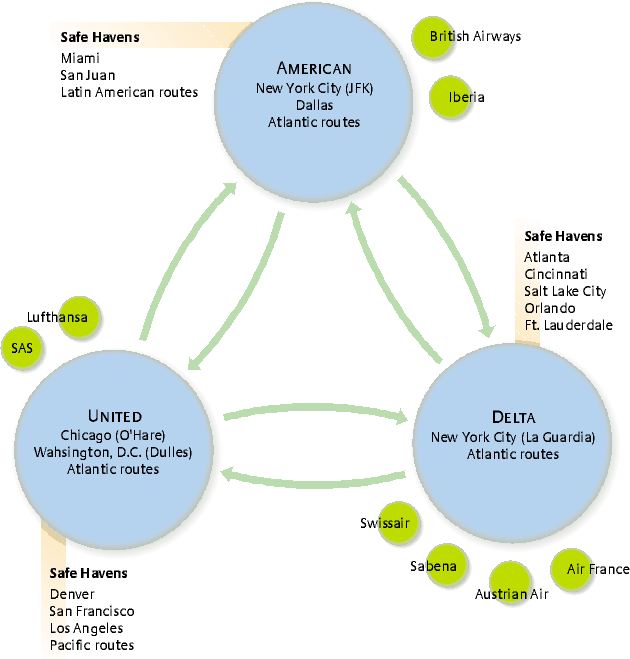

Consider the airline industry as it existed in the early 1990s. While the industry at that time appeared highly competitive to most observers, closer investigation reveals embedded patterns of pressure that mixed incentives to compete and cooperate. (See “Pressure Map of U.S. Air Carriers in the Early 1990s.”)

The map reflects that the industry leaders in the early 1990s were American, United and Delta — collectively known as the “Big Three Supercarriers.” These three had deep pockets and large hub-and-spoke systems with economies of scale and wider connectivity than the other carriers. Second-tier players were large national carriers that were not leaders for a variety of reasons. Some were financially weakened by a combination of hostile unions and excessive post-deregulation growth or competition (Continental and Eastern). Others were more concentrated regionally despite their national reach (Northwest and US Airways). Two low-cost niche players had arisen after deregulation: America West and Southwest. America West was built on a hub-and-spoke system, whereas Southwest focused on direct flights to secondary airports. Local and regional players, like Aloha and Alaska Airlines, were engaged in a struggle for the same geographic markets. And parts of the industry were suffering from aggressive, sporadic (some might even say almost continuous) price wars in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Fierce turf battles were being played out as competitors entered each other’s markets, resulting in numerous overlapping geographic markets that had not existed at the time of deregulation in the early ’80s.

When interpreting any pressure map, it is often helpful to start by looking at the current position and behavior of the industry leaders. Is there one firm (or a dominant coalition of firms) that seems to be applying a lot of pressure? Are the leaders aggressively applying pressure among themselves or just against lesser firms? Has a leader applied pressure that is so great it constitutes a major invasion or are the leaders avoiding contact by taking only minor positions in each other’s markets? Is the pressure exchanged between the leaders asymmetrical or balanced in intensity? Such questions naturally lead to others: Why are they acting as they do? Are there any explicit, implicit or even unconscious strategies unfolding? Who is central to the evolution of the system, driving the actions and position of others?

It is also useful to look for subsystems composed of smaller numbers of firms tightly organized in pairs or triangular relationships to see how their interdependence influences their behavior. Triangles may involve formal alliances or multimarket contacts that create mutual forbearance between all or just two of the members. The subset of firms may act as a united bloc, have a central player that influences the other two, or two members that share the third as a common rival.

Consider the incomplete triangle of Delta, Eastern and American. Although they are fighting over some of the same turf, Delta is pressuring Eastern, but not vice versa. Delta has taken large market share in markets important to Eastern, but Eastern has taken only minor positions in Delta’s important markets, giving Delta the advantage. This is a clear case of asymmetrical pressure. Delta lacks incentive to forbear with respect to Eastern’s markets unless Eastern were to take some moderate footholds in Delta’s most important markets (an opportunity that Eastern missed). In contrast, Delta and American each have moderate positions of about equal strength in the other’s markets. These “hostage markets” are not big enough to create a struggle over identical turf, as between Southwest and America West, but just enough to restrain Delta and American from attacking each other aggressively.

This type of mutual opposing and equally balanced pressure does not completely eliminate competition between two rivals, but has the potential to redirect it in two important ways. First, Delta is free to take on Eastern even more aggressively, without fear of a two-fronted battle against Eastern and American in different regions. Second, rigorous research in numerous highly competitive industries has shown that firms pressuring each other in this way often improve their profitability, avoid further expansion in the overlapping rival’s markets, limit aggressive actions to the rival’s least important markets, and focus on growth elsewhere. Rivals may even give up share in their weak markets in exchange for greater share in their strong markets so they both gain economies of scale.10

Looking at the third leg of the triangle, the mutual forbearance between American and Delta also influences the American-Eastern relationship. American is deterred from forging a merger or formal alliance with Eastern that would resuscitate Eastern with a cash infusion. In fact, after Eastern ceased operations in 1991, Delta benefited by picking up many of Eastern’s markets, giving it control of some “safe haven” airports. These included hubs and mini-hubs that were largely untouched by American, which could have invaded them were it not for the pressure-based incentives to avoid conflict with Delta.

Examining the pressure map of the early ’90s airline industry, one can see that several subsystems shaped how the industry consolidated and which carriers survived. There were four principal dynamic forces at work: Two-directional pressure between American and Delta and between American and United created a triumvirate of mutual forbearance that freed each company to put pressure on the second-tier players without the threat of intervention by another supercarrier. This allowed a division of labor among the Big Three, with American, Delta and United each targeting and weakening a different second-tier player. This further allowed each to focus its resources on one or two targeted carriers at most and enabled a downward pressure cascade, which tends to cause market consolidation. American was in a central position in the pressure system and played the role of enforcer. Whenever Delta and United acted against each other (because they lacked incentives for mutual forbearance), American was caught in the crossfire, forced to defend its interests and perhaps even to use disciplinary actions. These included the use or the threat of temporary but punishing market entries and price-based retaliation to keep the rest of the Big Three focused on the second tier rather than on one another.

Between 1990 and 1995, as a result of these dynamic forces, Eastern, Pan Am and Braniff all but disappeared. TWA, Continental and Northwest were financially weakened to the point that they could never make a play to join the Big Three, even if they had merged. US Airways acquired its main competitor, Piedmont, but was never financially strong enough to make a play for a leadership position in the industry. And Southwest won the low-cost niche, defeating America West and Midway.

By 1995, the original three-tier hierarchical pattern of pressure had consolidated into a stable power-sharing among the three supercarriers in which each dominated domestic hubs where the other two dared not expand, thereby improving profitability for each. (See “Pressure Map of the Big Three Supercarriers, 1995–2001.”) To perpetuate this favorable pressure system, they needed to stay out of each other’s most profitable turf and to refrain from placing further pressure on the remaining non-supercarriers to avoid antitrust issues. The non-supercarriers moved into the domestic territories not occupied by the Big Three, avoided aggressive competition in the supercarriers’ hub cities, or established positions in the less-traveled foreign routes to Asia or Latin America. The price wars of the early ’90s disappeared, and industry profits shifted from a $13.1 billion loss in the first five years of the ’90s to a profit of $23.2 billion from 1995 to 2000, according to the Air Transport Association’s 2001 annual report.

Funded by a stable home front, the supercarriers shifted their attention to the transatlantic market through alliances with European carriers, eventually dividing the market about equally. They launched their own Web sites and cooperated to create a joint Web site (Orbitz.com), selling airline tickets at a discount to put pressure on potential disrupters of the current pressure system, such as Priceline.com and Travelocity. With roughly equal market share and deep pockets, the Big Three competed only indirectly through international growth and improved operational efficiency from greater volume funneled from overseas. The pressure system remained more or less in equilibrium until the external shock caused by the events of September 11 destabilized it.

Proactive Intervention: Setting a Strategy for Competitive Pressure

In any industry, companies can develop competitive strategy by using a pressure map to answer two critical questions: If the current pressure pattern continues, what position will my firm ultimately hold? How can my firm stabilize or shift the direction of pressure to reduce (or enhance) the predicted impact of the current pressure system?

Had the airline industry’s second-tier carriers asked these questions, for instance, they could have countered the four principal dynamics that enabled the Big Three to control the downward flow of pressure. For example, the second-tier players could have weakened American’s enforcer role by attacking it from all directions. If American were besieged, the other super-carriers may have joined in the attack because an overwhelmed American could no longer enforce its threatened use of hostage markets. While it may seem implausible that simultaneous attacks by small players could vanquish an industry leader, it happens frequently. Sears, for instance, fell victim to upstart discounters, newly consolidated department store chains, new specialty catalogues, growing hardware franchisers, new category killers in consumer electronics and home appliances, and Home Depot.

Alternatively, some of the second-tier carriers could have consolidated and attacked the markets exchanged as hostages among two of the Big Three. By combining as one major player, they could also have worked to establish their own mutual forbearance with some of the supercarriers. While there would have been many obstacles to such a merger, it would have unraveled the triumvirate by forcing some of them to fight with each other and that would have alleviated the downward cascade of pressure. As a third possibility, Eastern, which was once one of the largest airlines in the world, might have moved to undermine the triangle formed by American and Delta by reallocating its routes to create mutual forbearance with at least one of those players.

Whether a company is the beneficiary or the victim of the pressure system in its industry, it can intervene to alter that system and gain strategic advantage through competitor and market selection, mergers and acquisitions or formal alliances, and other powerful strategic tools described below. Depending on the situation, the goal may be either to stabilize the current system or to destabilize it and redirect the existing pressure patterns.

Stabilizing the Pressure System

In 19th-century Europe, royal families cooperated in what was known as a “concert of powers” to control disruptive nations while continuing to compete among themselves for colonies, economic power and influence. In business, most industries have only a few leaders and they frequently exhibit a similar dynamic, as evidenced by the preceding airline industry example.

Similar to the “great power nations” of world history, industry leaders generally prefer stable systems and employ five time-tested mechanisms to achieve that stability: checks and balances; tit for tat; shared power systems; polarized blocs; and collective security arrangements.11 Over time, the use of these mechanisms signals each leader’s tolerances and limitations to the others. These mechanisms are used in sequence or in combination, depending upon the financial and strategic capability and will of an industry’s leaders to carry them out.

Checks and balances.

Industry leaders simultaneously use competitive pressure to hold ambitious competitors in check either by containing, constricting or undermining their growth and economic power. This was the case when the major airlines took on Peoples Express during the 1980s. Similarly, to support its Java programming language, Sun Microsystems organized an informal “everybody-but-Microsoft” alliance of software and hardware makers in the ’90s to check the power of Microsoft’s ActiveX language.

Tit for tat.

Individual leaders sequentially discipline potential rivals when they threaten the current pressure pattern, as American Airlines did when it acted as enforcer during the early ’90s, using selective fare wars to keep the other supercarriers off its turf. This pattern began at Texas airports during the ’80s when American played tit for tat against Braniff and Texas Air, two Texas-based airlines whose strong growth strategies threatened to preempt American’s home base in the Dallas/Fort Worth hub.

Sharing power.

Leaders achieve a consensus that no major competitor will attempt to disrupt the pressure system, as the Big Three Supercarriers did in the late 1990s. Each is free to pursue growth in new areas and to poach on nondominant players that are not cooperating with the coalition. However, if one of the leaders gains too much power, it will be ostracized and lose its influence. For example, Sony and Philips Electronics have evolved a power-sharing arrangement that has both tacit and explicit aspects. Sony has traditionally focused on the United States and Asia, while Philips has dominance in Europe and Latin America. The two share power over traditional Asian “fast followers” and component suppliers. Recently, the two companies entered into an agreement to develop a joint operating system for digital consumer-electronic systems that will network home computers, television, video games, personal digital assistants, home appliances and audio equipment. The intent seems to be to block Microsoft’s Windows CE from reaching prominence within the consumer electronics world. It remains to be seen if Philips’ recent troubles with high manufacturing costs and downsizing will make Philips a junior partner in the power-sharing arrangement. It also remains to be seen if Matsushita will be invited to adopt the Sony-Philips standard, forgoing historic rivalries to fend off the computing hardware makers that are converging on the digital appliance and home server markets.

Polarized blocs.

These are modified shared-power systems. When there are two or more leaders in an industry, they can enter into shared power arrangements in separate blocs of opposing alliances. Unlike shared power systems, a polarized bloc may include industry nonleaders. Polarized blocs compete with each other, but strongly encourage nonaligned players to join the blocs. Nonleaders that align with a bloc benefit from preferred relationships within the bloc, but can be ostracized if they refuse to take sides or prove disloyal. Probably the most well-known polarized blocs are affiliated with Coca-Cola and Pepsico. Their blocs include other beverage makers that distribute or bottle using the blocs as alliance partners, suppliers, bottlers, consultants and advertising agencies. This bloc system helped Coca-Cola and Pepsico contain Cadbury Schweppes’ attempt to form a new major player during the 1980s and 1990s.

Collective security arrangements.

These stabilize relationships among industry leaders and among lesser firms by giving all players an incentive for peaceful coexistence. Leaders in digital hardware (such as Nokia, IBM, Intel, Motorola, Toshiba and Lucent) as well as hundreds of less powerful firms (such as Acer, AMD, and Delco) have formed a collective security arrangement around Bluetooth, a designer and manufacturer of chips that enable short-distance, digital wireless connections. By spring 2000, more than 1,800 companies had agreed to use Bluetooth’s technology. The ostensible benefit for everyone is universal connectivity among all the devices that they make, but the other benefit is stability in the relationships among these players. Even if Bluetooth does not survive as the supplier of choice, it is unlikely that any single ambitious player will be able to use a new digital wireless technology to disrupt the status quo.

Destabilizing and Redirecting the Pressure System

An organization that is not benefiting from an existing pressure system or will not benefit from that system’s current path of evolution may want to destabilize it and redirect pressure among its rivals. This requires two crucial strategic choices: selection of the appropriate allies and selection of the appropriate target(s).

Interventions in a pressure system, based on alliances and targeting, can be used to signal dissatisfaction with the position or moves of a rival. They can also be used to entice, pin down or distract a competitor in certain markets. They can mold the market selection strategy of a rival, establish the borders between the market domains of two firms, force another player to converge on or diverge from a position, or eliminate a player or the allies of others. And targeting can create mutual forbearance or natural alliances between those with common rivals.

Allies should be selected to establish at least one of five clear types of alliances — each with a different strategic intent. Allies can be surrogate attackers that help a company conserve its own resources by putting pressure on a desired target. They can be critical supporters that help the company apply pressure to a common rival or passive supporters that refrain from pressuring the company while it puts pressure on another firm. In other cases, allies can act as flank protectors to relieve pressure on the company or as strategic umbrellas to prevent pressure on the company. In its early days, Microsoft used Apple and then Intel as strategic umbrellas, inhibiting IBM from squashing Microsoft before it became strong enough to stand on its own. Once IBM realized that Microsoft was a threat, IBM’s actions were inhibited by the potential reactions of the umbrella firms with which Microsoft had alliances. These five types of alliances can be established informally by signaling through public announcements or by applying pressure to create mutual forbearance, or they can be created formally through joint ventures and long-term contracts.

Desired alliance partners often ignore suitors’ overtures if they do not currently share interest in a common target or a common vision for the pressure system’s future. So it is up to the suitor to shape the potential ally’s interests. Public signals or formal offers of alliance must be preceded by competitive pressure to put teeth into the signal or offer. Methods for realigning the willingness of others to ally (or accept common targets) include the divide and conquer, balancer and assimilator strategies.

Divide and conquer.

By separating central players from their mutual forbearance or alliance relationships, each member of the coalition can be induced to reassess its position. Coca-Cola did this when it severed Pepsico’s 50-year Venezuelan distribution partnership with the Cisneros family by convincing the family to sign a more lucrative deal with Coke. Pepsico’s market share in its only real foothold in South America fell from 42% to zero overnight. American Airlines also used a divide-and-conquer strategy when it forced the breakup of a US Airways-British Airways alliance upon making its own controversial alliance with British Airways for transatlantic travelers. Resistance from government agencies in the United States and Europe ultimately gutted the power of the American-British Airways alliance, but American kept the alliance, perhaps to block British Airways from forming an alliance with one of the other Big Three.

Balancer.

A balancer throws its weight back and forth between rivals, enabling it (or the firm that encouraged it to get into the balancing act) to influence the rivals’ positioning and movement. For example, in defense contracting, Boeing and Lockheed Martin compete for major contracts. Winning the contract depends upon the support of radar and avionics suppliers (e.g., Northrop Grumman) and airframe designer/manufacturers (e.g., British Aerospace) that regularly switch allegiances between the two defense giants. Their influence is considerable because contract awards are typically all or nothing. The jet engine manufacturers (e.g., General Electric, Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce) have chosen not to play this game, often supplying whoever wins the contract.

Assimilator.

This strategy is based on acquiring the tacit or formal alliance partners of your rivals, balancers and/or your rivals’ rivals. Assimilation can be accomplished through merger and acquisition or through exclusive supply or distribution contracts. For example, in 1998 and 1999, Microsoft paid $5 billion for a chunk of AT&T, $600 million for a stake in Nextel, $200 million for a piece of Qwest Communications, $1 billion for a portion of Comcast, $400 million for a stake in Canada’s Rogers Cable, $212.5 million for part of Road Runner cable modem service, as well as making investments in several dozen other telecom and cable companies. Sun Microsystems’ CEO Scott McNealy saw this as an assimilation strategy to squeeze his company, since Sun’s biggest business at the time was selling Sun’s Solaris Unix operating systems to communications companies, its largest customer segment.12

In choosing the right targets, several options exist. A company may want to take on its biggest threat, the weakest of the major players, a rising or aggressive player, or a competitor that doesn’t pressure it directly but represents an attractive market. The choice usually depends on the targeting firm’s goal for the pressure system’s future pattern, the feasibility of the action and the opportunities that present themselves.

Consider AOL’s Internet service provider business in Europe. Despite coming late to the market, by 2001 AOL had attained the number three position in a fragmented market with three other leaders: number one T-Online (based in Germany), number two Tiscali (Italy) and number four Wanadoo (France). T-Online, a Deutsche Telekom (DT) subsidiary, is by far the largest European ISP and holds the leadership position in its home market because its service is provided, by default, to DT subscribers. T-Online has had some trouble replicating its success outside of Germany but does have a presence in several other countries and grew 35% in fiscal year 2001 to 10.7 million users. Growing-but-weak Tiscali has made numerous small acquisitions in 15 countries, but it holds only the number three or four position and has low brand recognition in most of them. In its home market, it holds only the fifth spot. Wanadoo has a strong position in its home market, as well as a strong position in the United Kingdom because of its acquisition of Freeserve, the country’s top ISP.

In this case, AOL had several options: Attack or acquire into the leader’s (T-Online’s) home market; target markets not important to T-Online; go after the home market of the most vulnerable player (Tiscali); or target no one and grow diffusely across Europe. While AOL is making inroads across Europe, it appears to be targeting T-Online. AOL is exerting significant effort in Germany, packaging its content to keep its users online 2.5 to 4 times longer (by different estimates) than T-Online users, suing DT over its allegedly favorable telephone rates for T-Online users in Germany and using massive ad campaigns to capture German users. Because T-Online lacks any counter-pressure through a foothold in AOL’s home ISP market (the United States), AOL has not been constrained from its aggressive efforts.

Most industry leaders prefer to fight small battles rather than large, risky ones, so they target the most vulnerable player. However, this is not always the best choice. It is often better for a company to redirect pressure away from itself or to weaken several players simultaneously than to eliminate the weakest player, because the latter scenario leaves major competitors capable of exerting a lot of pressure. Not targeting the weakest player may leave more rivals on the field, but each with reduced focus and power.

Consider General Motors’ position in the automobile industry. Its home market is the United States, but it has a strong foothold in Europe (its Opel division). Ford presents a strong challenge in the U.S. and also has a strong position in Europe. Toyota has the dominant position in Japan, with a strong and expanding foothold in the U.S. DaimlerChrysler has a strong position in Europe and a weak position in the U.S. GM could target the weakest global player, DaimlerChrysler, which is in financial difficulty, but it would still face two powerful competitors (Ford and Toyota). Or it could target the strongest competitor on each continent: Ford in the U.S., Toyota in Asia and Daimler in Europe. This seems to be GM’s preferred strategy, as evidenced by the fact that it has been buying up or taking minority stakes in the weaker players of Asia and Europe. This strategy may be difficult to realize, since both Ford and Toyota are strong in the U.S. and Toyota’s position in Japan is unassailable given the existing trade and cultural barriers. But in the unlikely event that GM succeeds, it would become the undisputed global leader, facing three weakened competitors.

Enhancing the Pressure Map: A Look at the European Wireless Telecom Industry

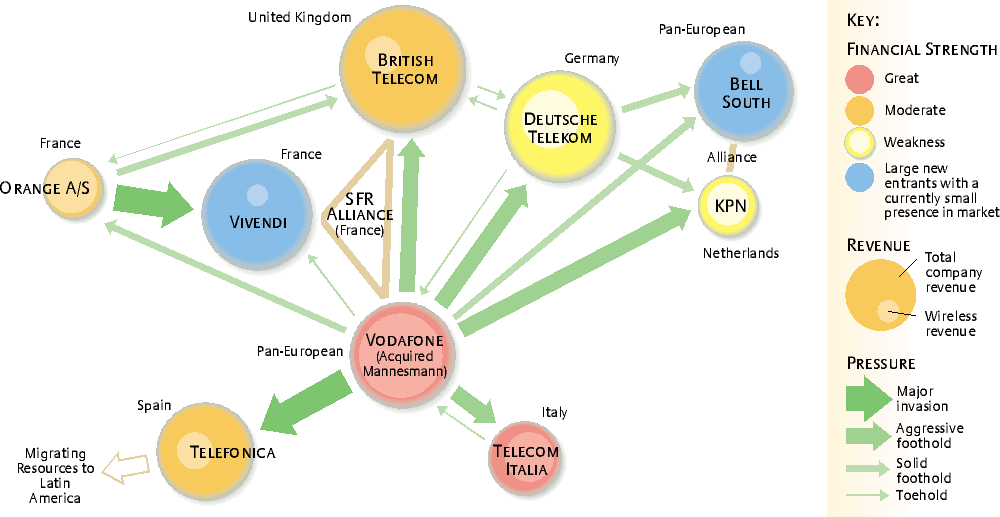

The at-a-glance information in a pressure map can be greatly enhanced in a number of ways. Safe havens (relatively uncontested markets), formal alliances and an industry’s stabilizing mechanisms can be shown graphically. Circles can be color-coded to indicate the financial strength of each company. Interior circles can be included that are proportional to the size of a company in the markets being considered or in its home geographic or key product market. The arrows can be color-coded to reflect relative advantage in price, advertising, innovation quality or service. Dotted arrows can be added to indicate the migration of the players to markets outside of the industry, with the size of the dotted arrow representing the magnitude of resources being devoted to the move.

An enhanced pressure map can concisely present a considerable amount of information about the balance of power in an industry. Look, for example, at the industry landscape that was created when U.K.-based Vodafone acquired Germany’s Mannesmann in June 2000, forming a pan-European giant with $24 billion in revenues and 34 million customers — in an industry that had previously been operated by nationally dominant state-owned or -regulated firms. (See “Enhanced Pressure Map of the European Wireless Telecom Industry, 2001.”)

In 2002, Vodafone is the undisputed industry leader with lower subscriber acquisition costs and greater economies of scale and connectivity than its competitors. It has strong, positive free cash flow and holds strong positions — approximately one-third of the home market — against each of the national wireless leaders in Germany (DT), Italy (Telecom Italia) and Spain (Telefonica). It’s partnership with Vivendi, SBC Communications and British Telecom, called SFR, holds a third of the French market against France Telecom’s Orange A/S.

The enhanced pressure map of the wireless industry helps make sense of a seemingly simple situation that has triggered complex maneuvers with sometimes-obscure rationales. On the surface, the map indicates clearly that, in 2001, players such as British Telecom, France Telecom’s Orange A/S and DT were on the defensive and had to counter Vodafone if they wished to avoid becoming second-tier players. The simple solution — an assimilation strategy — would have been to merge their mobile operations, attract several smaller players and form another pan-European mobile telecom, a powerful counter-balancing rival to Vodafone, thereby creating two polarized blocs in the European wireless industry. But this strategy would have been politically impossible, given the current nationalistic regulation of European telephone companies.

Analysis of the map also suggests that the players could check and balance Vodafone in more complex, but still effective, ways. That seems to have been the chosen strategy, and, in 2002, Vodafone has begun to feel the counter-pressure. In Germany, Vodafone faces a strong defensive counterattack from DT. Vodafone lost 400,000 subscribers in that country in the first quarter of 2002 alone. In its home U.K. market, Vodafone is in a tight market-share race with British Telecom’s Cellnet (rebranded mmO2), France Telecom’s Orange A/S, and DT-owned One2One (rebranded T-Mobile). Given its active defense in Germany, DT is aggressively attacking and taking market share in the United Kingdom, unfettered by fear of Vodafone retaliating in the German market. France Telecom’s Orange A/S is even more aggressive, attacking Vodafone in the United Kingdom, unconstrained by fear of counterattack in its home market where it holds 43% market share.

Vodafone appears to be trying to hold its market share position against British Telecom and France Telecom’s Orange A/S in the U.K. to reduce its pressure against DT in Germany and to concede to Orange A/S in France. Meanwhile, Vodafone’s strategy seems to include attacking Telecom Italia — its financially strongest opponent but lacking the multimarket contact to counterattack elsewhere — and Telefonica, which has demonstrated a lack of commitment to Europe by migrating excessively (dotted arrow) to Latin America.

The SFR alliance, originally conceived as a counterbalancing move against France Telecom by two British firms (Vodafone and British Telecom), is troubled by the conflicting interests of its partners, including an intense rivalry between Vodafone and British Telecom in their home market and Vivendi’s redeployment of resources to the entertainment industry. Vodafone was reported to be interested in buying out Vivendi’s stake13 — perhaps to make SFR an aggressive counterbalance against Orange A/S in France once again — and British Telecom has indicated its willingness to sell out as well.

In addition, Vodafone is reportedly considering exiting its joint venture with Verizon in the U.S. wireless market to bring cash home to support its European initiative. This may be necessary because of the rising counterpressure from rivals, the fear of a consolidation of several rivals if political conditions were to permit, and the need for funds (for initiatives such as 2.5 and 3G technology) to remain the leader.

The European wireless industry illustrates how an enhanced pressure map can enable “what if ” exercises and contingency planning, allowing all players to anticipate with greater accuracy the outcomes of their own or others’ potential strategies. In fact, if Vodafone’s competitors had used pressure mapping to do what-if analyses, it might have stimulated a more aggressive preemptive assimilation or alliance strategy among them before Vodafone acquired Mannesmann.

Putting Competitive Pressure in Context

As the old military maxim goes, a good plan never lasts longer than contact with the enemy. But, by using competitive pressure maps and a systems approach to understanding the dynamic patterns underlying multimarket contacts within an industry, competitors can make a good plan for making contact with enemies and allies alike.

Systems of mixed cooperation, competition and forbearance exist in every industry and are not necessarily anticompetitive, collusive oligopolies. Pressure maps are not intended to encourage firms to conspire in smoke-filled rooms. They merely indicate and help predict the economic incentives for, and consequences of, given actions. If taken too far, of course, mutual forbearance can reach the point of collusion, but there is a lot of room for cooperation before it reaches that stage. In fact, if used properly, pressure mapping can actually reduce the temptation to collude, drive industry growth to new heights and in new directions through increased indirect competition, and make room for clever small players that act as balancers or members of polarized blocs and collective security agreements. In the end, use of pressure and mutual forbearance must be responsible and tailored to avoid violation of antitrust and any other relevant national laws. As with any strategy, companies should use their ability to change the pressure situation in their industries for the greater good of shareholders, customers and society as a whole.

Although the general logic and strategy of pressure systems will apply to a wide variety of situations involving geographic and product markets, there are industries in which pressure patterns are obvious and maps may not be revealing. Still, evidence of significant profit impact from pressure based on multimarket contacts has been found for industries as diverse as banking,14 cement,15 hotels,16 knitwear manufacturing,17 mobile telephone service18 and petroleum19 — on both the global and local levels.

Of course, competitive pressure is not the only force that affects profitability and survival. To be effective, pressure maps must be interpreted in the context of the macroeconomy. Major discontinuities, such as terrorism or technological revolution, can destroy even the most stabilized systems. And firms can implode from labor problems, poor management and implementation errors that shift the balance of power among the players to stronger players outside the current leadership.

The changing nature of industries and the external forces that affect them suggest that pressure systems require constant reexamination. And pressure mappings can show dynamic shifts in a visual way. Indeed, if several maps done at periodic intervals are viewed electronically in rapid sequence, like an animated film, an industry can be seen evolving, providing a powerful and visceral understanding of how the world is moving and how the pressure is flowing.

References

1. R.A. D”Aveni, “Strategic Supremacy: How Industry Leaders Create Growth, Wealth and Power Through Spheres of Influence”