Is It Really Lonely at the Top?

Maybe not. Life revolves around three social spaces: personal private space, public or work space and a kind of “social courtyard” space in between the two. Savvy executives learn to develop relationships that thrive in that in-between social courtyard space.

Topics

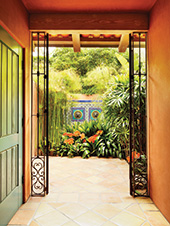

Physical courtyards serve a unique function in mediating between public outdoor space and private indoor space.

Last summer, we were strolling through the streets of Madrid when we came upon an unexpected entrance. A heavy wooden door stood open, offering passage from the crowded city street to a beautiful, enclosed courtyard. The hushed space, framed by lush green plants, was surrounded by sky blue walls that reflected the delicate floor tiles. A mirror hung on one wall, and on the opposite side was a stand for umbrellas and a place for shoes.

Another door at the back of the courtyard led to a private space. It was closed.

Internal courtyards are common in European cities. In the summer, the shaded confines of a courtyard cool the hot fumes from the street before they reach the private space. During winter, the courtyard’s sheltering walls temper icy blasts. The mirror allows for one last appearance check before entering either the public or the private space. Wet umbrellas and shoes can be temporarily discarded so as not to sully the private space and then picked up again upon leaving.

Physical courtyards serve a unique function in mediating between public and private spaces and between the public outdoor world and the private indoor one. Physical spaces have analogous social counterparts. From our perspective, life revolves around three social spaces: personal private space, public or work space — and what we call courtyard space. Each of these spaces can be associated with a certain type of relationship: friends, allies and what we call “chums.”

Personal space is occupied by friends, a term we use to indicate relationships where acceptance is close to unconditional. You may not like some of the behaviors of your closest personal friends, but the relationships will probably continue. They have been, and likely will remain, part of your inner circle.

The public space, by contrast, is the social sphere of highly conditional relationships. These relationships come and go, lasting only as long as they help both parties achieve valued goals. Colleagues, clients, prospects, acquaintances, customers, teammates, bosses, peers, classmates and subordinates are all members of conditional relationships, and they all occupy the public social space.

In the business world, colleagues, peers and other contacts work together as what we call allies when it is in their mutual self-interest to do so. They can easily oppose one another in one area of work while agreeing in another. One might feel anger and hostility toward a business ally because he or she works against one’s self-interest, but one should not feel a sense of betrayal. Only friends can betray.

But there’s a third kind of business relationship that’s often overlooked: the relationships in between friends and allies — in other words, business relationships with people you enjoy being with. We call these people chums, and we think their importance too often goes unnoticed. Chums occupy a space that is not quite the same as the one inhabited by either friends or business allies.

The social courtyard is the space for turning allies into chums. Dale Carnegie’s best-selling book How To Win Friends & Influence People is not, in fact, about making friends in the sense of forming unconditional relationships. It is instead a practical classic on the art of cultivating chums — of inviting business allies into your courtyard while keeping them out of your kitchen.

The tools for developing chums are seldom taught in business schools or in corporate leadership programs — yet the art of doing so is critical to all companies that operate in the knowledge industry, where productivity often depends on people developing effective business relationships that enable them to work well and efficiently with others. Business-development professionals, for example, are on the front lines of client acquisition: They cultivate prospects for specific assignments and perhaps turn them into clients. Using this framework, they convert contacts into allies.

However, successful rainmakers go one step further: They turn clients who are allies into chums. Indeed, rainmakers are perceived to “own” the client relationship because when they leave a company, many clients end up following their chums. This emotional bonding clearly differentiates rainmakers from other business-development professionals — and has business benefits. Rainmakers understand that inviting business relationships into the courtyard of their lives is not the same as inviting them into their kitchens.

One of the tools for developing chums is the smart use of the courtyard concept. Consider the golf course. Playing 18 holes can easily consume four or five hours of time away from the work space. The traditions that surround the game — the language used, the acceptable response to a particularly poor or outstanding shot, and so on — discourage private-space behavior and spontaneity about anything other than the game at hand. The business purpose of golf is to convert allies into chums, though it is not the only activity that could be considered for that goal. Taking clients to the theater and then talking about the show over dinner could also be considered courtyard time.

The social courtyard can mediate time demands between personal and professional spaces. Activities such as volunteer work in professional or industry associations or in one’s community can help to recalibrate work/life balance and develop allies into chums. New business relationships can be cultivated from unexpected sources and help moderate the time demands of one’s profession without turning one’s back on it.

You’re probably familiar with the business cliché that claims “it’s lonely at the top.” The idea is that powerful people have few real friends but many superficial relationships from which they derive little emotional satisfaction. Our experience in working with successful corporate leaders suggests otherwise: Yes, these executives may have only a few intimates. But their world is crowded with chums, with whom they enjoy spending time. They are far from lonely — because they have mastered the art of relationships in the social courtyard.