The Need for a Corporate Global Mind-Set

Topics

When a certain U.S. multinational corporation sought to adopt a global policy on employee mobility, it convened a yearlong symposium with representatives from units worldwide. Through a format that encouraged brainstorming and in-depth discussion, a consensus gradually emerged that enabled executives to reduce mobility classifications from eight to two. One category, the expatriate assignment package, encompassed managers who agreed to a company-requested posting of two or more years; it included 23 core elements that were standard. The other category, the international assignment package, covered employees who were assigned to a position for less than two years or requested an international posting; that had 13 core elements and left the other 10 adjustable to local situations. Both the policies themselves and the process used to develop them were well received abroad.

In another U.S. multinational, however, a task force of U.S. employees from different levels and functions drafted a major revision of work-force policies. The draft was discussed in several managerial forums, and a detailed questionnaire solicited the opinions of all U.S. personnel. Corporate executives considered the final product, which reduced the number of policies from 120 to 10, a notable success. Unfortunately, the process included little input from overseas. Instead, headquarters presented the results to all geographic units as a fait accompli. A company executive later commented, “International participation was an afterthought.” The policies and the process were not well received abroad.

Both companies had progressive reputations. Why then did they approach international involvement in such different ways? A corporate global mind-set was the critical difference: The first company showed it, whereas the second did not. We define a global mind-set as the ability to develop and interpret criteria for business performance that are not dependent on the assumptions of a single country, culture or context and to implement those criteria appropriately in different countries, cultures and contexts.1 The global mind-set is a critical component of globalization. And as often noted, the truly globalized corporation is more a mind-set than a structure.2

Getting to a corporate global mind-set requires individual managers to demonstrate a glocal mentality, which features three components.3 First, think globally; recognize when it is beneficial to create a consistent global standard. Second, think locally: The process of becoming “truly global … means deepening the company’s understanding of local and cultural differences.”4 Third, think globally and locally simultaneously; recognize situations in which demands from both global and local elements are compelling. Our research reveals that the corporate version of an individual manager’s global mind-set emerges from policy development led by a core group. A core managerial group with a glocal mentality is an essential component of a corporate global mind-set.5 However, such a mind-set will not become embedded in an organization until executives pull the structure, process and power levers to activate it. Then the newly glocalized lower-level managers will pull their levers to convert employees in cascading fashion through critical parts of the company.

Formerly, it was possible for a close-knit network of leaders to handle organizational tensions through informal dialogue. But as businesses grew more complex, fast-paced and dispersed, a small group could no longer do everything, necessitating a broader base of managers to share in global decision making. Lacking globe-spanning experience, the broader group often demonstrated a parochial view just when global expansion was tearing the fabric of home-country-bound corporate cultures. That’s why the global mind-set is such a vital evolutionary adaptation, one that helps companies give recognition, respect and representation to all employees while improving agility and competitiveness.

On the Road to a Global Mind-Set

To increase its global presence, a company must manage its global work force. Geographic dispersion and cultural diversity create challenges in their own right. The prospect of uniting employees in pursuit of company prosperity is further daunting. Yet success depends on a corporation’s ability to direct employee behavior toward collective goals. Thus, a company must optimize its relative emphasis on worldwide requirements and country variations.

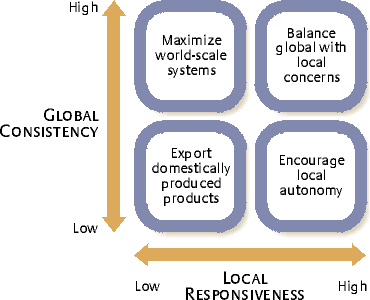

Academics have long highlighted the need to adjudicate between global consistency and local responsiveness.6 Ill-advised scope can have far-reaching implications: Companies that short-change global reach lose opportunities to maximize efficiencies and consolidate costs; companies that shortchange local responsiveness endanger market share and alienate employees.

For example, tensions surfaced at Sun Microsystems when local managers were accorded wide discretion in adopting employee stock-option plans. The longtime practice perturbed the central human-resources and finance executives, who wished to manage incentive compensation as a strategic tool. Conversely, Cisco Systems pushed for a global culture that encouraged employees to disregard hierarchy, upsetting Asian employees’ tendency to look to higher levels for authority.

A grid can help crystallize the organizational parameters. (See “The Global Consistency/Local Responsiveness Grid.”) Companies that emphasize global consistency seek cost advantages by maximizing world-scale systems. Those maximizing local responsiveness adjust for country differences by allowing local autonomy. Those combining both dimensions use mutually inclusive arrangements.

There are no pure types; all organizations must optimize the balance between two forces inherently at cross purposes. Variables such as industry sector, company strategy and organizational capability will pressure companies toward different points. Even within companies, functions have different grid locations. Marketing, for example, often must respond to local tastes, whereas finance pursues a globally unified approach. In addition to such complexities, work-force management decisions must take into account the cultural, governmental and social dimensions that affect human behavior and limit managerial discretion.7

To enact the particular work-force management approach that best fits their company’s positioning on a consistency vs. responsiveness continuum, managers need tools. The two most often used criteria for evaluating management decision making have been effectiveness and efficiency. Effectiveness means extracting maximum gain from the external environment; efficiency is the ability to secure optimal use of internal resources. But work-force management policies also directly affect employee well-being, so recent studies accent the importance of a third criterion, fairness.8 Policies judged as unfair will be resisted and hence will be neither efficient nor effective.

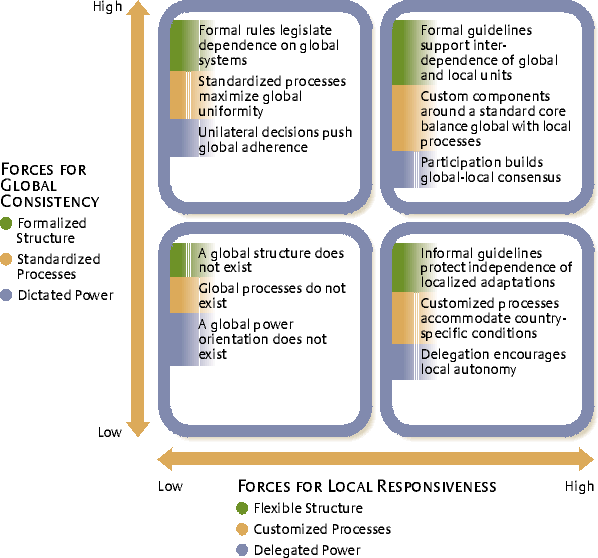

In our research, executives strove to deal with all three work-force management concerns amid the tensions of the competing forces. For effectiveness, they structured policies to channel employee behavior toward productive activity, asking, To what extent should policies be set as formal regulations or as flexible guidelines? For efficiency, they streamlined the process for policy enactment, framing the key question as, To what extent should policies be universally standardized or locally customized? And they sought to enhance fairness by locating the power to develop policy at the suitable level of organizational hierarchy, asking, To what extent should policies be centrally mandated or geographically delegated?

When the dimensions of each tension are placed in a grid, the resulting planes clarify options available to decision makers in formulating policies worldwide. (See “The Three Tensions of a Global Business.”) Policy development challenges managers to enact the skill contours of a glocal mentality — that is, to recognize when global consistency, local responsiveness, or a balance of global and local tensions is best. By dealing with the tensions, companies can ensure that the glocal mentality of individual executives becomes embedded enterprisewide.

The Structure Tension: Global Formalization vs. Local Flexibility

The primary structural tension concerns the proper mix of rules vs. guidelines (and guidelines can be formal or informal). A case in point, U.S. companies continue to wrestle with enforcing the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. The act prohibits bribery of foreign officials to procure business. Following a formal-rules approach, Intel strictly defined a bribe as “a thing of value given to someone with the intent of obtaining favorable treatment from the recipient.” The company specifically proscribed payments to expedite a shipment through customs if the payments did not “follow applicable rules and regulations, and if the agent gives money or payment in kind to a government official for personal benefit.”

Texas Instruments adopted the middle way, a formal-guidelines approach. It called on employees to “exercise good judgment” in questionable circumstances “by avoiding activities that could create even the appearance that our decisions could be compromised.” TI further required employees to abide by the letter and spirit of the company’s code of conduct as well as country laws. Analog Devices, following an informal-guidelines approach, set up a policy manager as a consultant to overseas operations. The policy manager helped callers think through the issues and informed them how the corporate office handled similar situations — but also emphasized that the decision was local management’s.

The Process Tension: Global Standardization vs. Local Customization

The primary process tension concerns the appropriate blend of uniformity and uniqueness in worldwide processes. Companies deal with the tension when they ponder the development of processes for performance reviews, for example. Adopting a standardized-process approach, EMC identified 15 competencies required of all executives. The company initiated a process to evaluate managerial performance against the same competencies worldwide, using a standard form and a common set of defined steps. The executives in our study believed it provided a basis for evaluating talent and developing managerial skills.

IBM sought to customize performance appraisal processes around a standard core. Dimensions that reflected its win/execute/team core values were mandatory. But the company allowed customization of particular steps in the process according to national, divisional or functional needs. The number of items rated and their effect on pay differed by country. Meanwhile, GTE opted for customized processes in its international units and encouraged (but did not require) overseas operations to tap the expertise of other units and headquarters.

The Power Tension: Global Dictate vs. Local Delegation

The primary fairness tension involves the locus of power in the exercise of worldwide decision making. Corporations address the tension as they consider how to design and implement incentive compensation schemes. Recently, companies have reacted differently to questions about who should decide the form and amounts of such incentives. The questions are particularly relevant to the power-orientation dimension.

SCI Systems, a company that globally enforced its unilateral policies, developed the same reward formula for top managers in each of its 35 plants worldwide. Sun Microsystems took a participative approach. In response to requests from country units, it sought to extend profit sharing worldwide. Negotiated agreements between country units and corporate headquarters ensured that both corporate requirements and local needs were accommodated. At Seagate Technology, control was delegated to local units, which were responsible for adapting incentive schemes to their needs.

Applying the Model

Use of the structure, process and power-orientation grid helps embed a corporate global mind-set. But because top managers control the necessary levers, they must have a glocal mentality themselves as well as a vision for guiding the company toward a global mind-set. When a core group initiates a process to identify the optimal configuration of global and local elements, it can begin to establish its mind-set in the company. In the context of policy development, application of a global mind-set requires executives to recognize options presented by various locations in the grid. Then they can make decisions that maximize three important kinds of consistency: consistency across the structure, process and power dimensions within each policy; consistency between policies; and consistency of the policies with the values guiding the company’s approach to global work force management. Within-policy and between-policy consistency are virtues only if alignment occurs with values. So a corporate global mind-set also is demonstrated in the emphasis on the values that guide a company’s orientation toward work force management issues.

Within-Policy Consistency

Choices made on the structural, process and power-orientation questions are interdependent. Consistency across the grid is desirable; inconsistencies generate problems. For example, in the past, Hewlett-Packard’s benefits managers tried to combine insurance coverage of many countries to get volume discounts. Following the company’s consensus-oriented culture, a task force was formed that spanned national, divisional and hierarchical lines. After a lengthy process, member support was split among several alternative plans attempting to address concerns of all parties. Minimal cost advantage was obtained. The integrative task force’s processes and the company’s participative orientation combined to undermine the formal rules needed for cost savings. More recently, as part of a move toward accentuating the primacy of performance, a few executives at headquarters formally centralized the criteria for insurance vendor selection, identified substantial cost savings through worldwide pooling, and then communicated the selected vendors and rationale to benefits managers in various countries.

Between-Policy Consistency

Policy optimization occurs when a policy not only shows internal consistency but also fits with other company policies. The resulting alignment reduces friction and supports global efforts. More than one-third of the companies studied were in various stages of completely overhauling work-force management policies. A goal was to purge the policy set of inconsistencies and mixed messages. Compaq, for example, having acquired Digital Equipment and Tandem within a short period, sought to create unified work-force management policies. The task was rendered especially difficult by Digital’s extensively detailed policies and by some idiosyncratic Tandem policies that reflected its Silicon Valley heritage. Hewlett-Packard’s recent acquisition of Compaq has generated a new round of policy alignment to merge divergent corporate cultures.

Policies’ Consistency With Values

A company can attempt to change its policies for global work-force management, but it also must align them with corporate values. By the same token, policies can be valuable in recasting company values.9

For example, when Texas Instruments shifted from predictable competition for defense-related contracts to volatile markets for fast-changing, high-technology products, executives jettisoned the company’s massive policy manual. To herald movement from the high consistency corner of the grid toward a position closer to the high consistency/high responsiveness corner, TI sought worldwide participation to identify a few values that embodied its evolving philosophy. It then developed formal guidelines to facilitate the interpretation of its major global policies. In the words of an executive, TI exchanged a strictly defined “Ten Commandments” for “Six Commandments and Four Suggestions.” Supported by a succinct pamphlet communicating the revised values, the approach was a powerful stimulus to organizational change.

Choosing a Location on the Consistency/Responsiveness Grid

In choosing a position on the grid, companies should consider their particular situations. A need for global consistency would favor policies that accentuate formalization, standardization and global dictates, whereas a need for local responsiveness would favor flexibility, customization and delegation. U.S. companies operating abroad gravitate toward global consistency through heavy emphasis on formal rules, standardized processes and headquarters control, an approach that elicits charges of insensitivity and even colonialism.10 However, companies that permit local autonomy forgo the benefits of global scale and cross-national learning. When companies need both dimensions, policies that allow balance are best.

In practice, relatively few companies have been able to move in the high consistency/high responsiveness direction, an increasingly attractive location that can modulate difficulties when strategic direction faces cross-cultural constraints. For example, the need for U.S. companies to enforce consistent behaviors for the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act may create a challenge for companies that favor locally responsive policies. However, the German requirement to consult employee representatives prior to major decisions necessitates that U.S. companies moderate any preference for consistency. When companies face both kinds of demands, a high consistency/high responsiveness pattern offers flexibility in handling pressures.

Several executives we interviewed maintained that work-force management policy decisions, in particular, require an increasingly high consistency/high responsiveness approach. They argue that a company’s vision and values must show global consistency. However, a company’s workplace practices, which translate policy guidelines into day-to-day procedures, should be locally determined. The only way to integrate philosophy and practice is through policy guidelines.11 Further, in a multicultural work force, corporate values will inevitably clash with local cultural values. Solutions that are high in both consistency and responsiveness preserve a balance and avoid either forcing corporate values on the local culture or acquiescing counterproductively to local values.

Although there is progress in functions such as marketing and new-product development, our research indicates that a glocal mentality has yet to take hold with human-resources executives, the prime custodians of work-force management policies. Once labeled the most local of corporate functions, HR has shifted toward an emphasis on consistency in worldwide corporate culture and the policies and programs that support it. HR also must pay heed to national culture, government fiat and idiosyncratic social systems, but even as HR executives widely hail the glocal mentality as a key managerial competency, many remain uncertain how to move their own managers toward it.

HR can greatly influence a company’s ability to inculcate a glocal mentality. Given the glocal mentality’s increasing importance, what are the organizing principles that enable company executives to encourage it in work-force management issues? Academics in international management, organizational design and corporate culture have begun to identify ways to create opportunities for glocal thinking and to describe the activities of executives who have translated their glocal mentality into a corporate global mind-set.12

Developing a Global Mind-Set

Developing a global mind-set requires movement toward the high global/high local corner of the structure, process and power grid. That involves balancing formalization with flexibility through modular networks and communities of practice; balancing standardization with customization through distributive management, centers of excellence and corporate vision; and balancing global dictates with delegation through the application of procedural justice.

Balancing Formalization With Flexibility

Two approaches that managers can use to ease the inherent tension between global and local structure are modular networks and communities of practice.

Modular networks.

In between the dependence that formal rules impose and the independence that informal guidelines encourage, the formal-guidelines approach fosters interdependence. Executives should seek avenues of mutual reliance and benefit, crystallized around modular networks. Instead of emphasizing formalized headquarters communication to divisional and regional units, the webs created by modular interaction underscore a more flexible give-and-take among the divisions and units themselves. Thus, in an effort to increase cross-unit communication, GTE and MediaOne emphasized serving as consultants to geographic units. GTE executives posed a challenge: “We have global talent; how can we use it globally?” They referred country units experiencing problems to other country units that had solutions. Soon the Puerto Rican unit, which had considerable experience with broadbanding, reached out to the Venezuelan unit, which had needed advice. Flexible adjustments to broadbanding, suggested by the Puerto Rican unit, enhanced the likelihood of successful implementation in Venezuela.

To integrate the network, executives must reinforce its use. A key requirement is to reward managers for synergistic cross-unit projects. At General Electric, where cross-unit collaboration is an integral component of the management culture, executives are recognized for using it.

Communities of practice.

Another integrative device is communities of practice.13 At NCR the first community consisted of a worldwide intranet site using proprietary technology called “Round Table,” which let the company’s compensation professionals resolve problems and share innovative approaches. Active contributors to the community were rewarded.

Balancing Standardization With Customization

Distributive management, centers of excellence and corporate vision assist managers in resolving process tension.

Distributive management.

Distributive management accords significant decision-making responsibilities to managers in dispersed locales and provides the resources to implement the decisions. Distributed resources enable integration of standardization with customization. But executives must ascertain a company’s work-force capabilities worldwide. Many companies with a sophisticated U.S. skills-inventory system lack such systems overseas. Hence a software-services company encountered the perils of negotiating large worldwide contracts. Without a worldwide skills inventory, the company was flying blind. Whenever it was successful in the bidding process, the company had to scramble to find ways of servicing the contract. Consequently, management was sometimes immersed in last-minute efforts to build capabilities in new locales. That made it hard to provide good service and hampered cost control.

Centers of excellence.

The next step is to determine how to distribute responsibilities and resources across geographic locations. Through centers of excellence around the globe, companies can effectively leverage capabilities by parlaying strategic knowledge to other units.14 For example, strict employment laws and strong unions in France encourage expertise in manpower-planning systems. That knowledge can cascade across the company by means of a center of excellence. Although increasingly prominent in fields such as marketing, information systems and research and development, the notion of distributed centers is not yet ensconced in human-resources management.

By strengthening the role of regional headquarters, companies can counterbalance the current predominance of industry-based structures and worldwide divisions that push for standardization. Regional groups can become centers of excellence developing customized organizational capabilities. Most companies already have regional headquarters to represent, at least for administrative functions, Europe, the Middle East and Africa; the Asia-Pacific area; Latin America; and North America. SCI Systems executives believe that intraregional interests lend themselves to cross-unit meetings, whereas cross-regional assemblies share fewer problems. Oracle has focused its shared services at the regional level to attain high effectiveness at low cost, reasoning that “someone answering a phone in Iowa is not going to know much of what affects a caller in Europe or Asia.” IBM is also retreating from global policies to focus more attention on regional centers. It believes direct movement to worldwide processes might be too great a leap, if even desirable. Regionwide policies carry potential because of cultural similarities within a group of countries.

Corporate vision.

Integrated networks also allow managers latitude to develop a customized solution for their locale, based on awareness of alternatives used elsewhere in the organization. The challenge is to ensure that customization takes place within shared parameters. That means top management must stimulate a global mind-set by promoting a corporate vision that values glocal thinking. The process for inculcating the overarching vision is socialization.15 Companies must provide opportunities for managers to interact in forums. Message dissemination can occur through worldwide conferences and meetings, electronic-communication technology, executive role modeling, measurement and reward systems, and worldwide rotating assignments. Such processes of “glue technology” promote trust and solidify bonding.16 Corporate education centers serve the purpose well. Focused management-development programs are useful if a company wishes to signal changes in the vision. When Texas Instruments recast its core values, it instituted management development programs. The sessions underscored the need for a new vision, established parameters for desired changes and defined action steps.

Balancing Global Dictates With Delegation

Procedural justice can assist managers in resolving tension over power.

Global dictates often yield substantially uneven benefits, depending on locale, and thus impede distributive fairness. In such situations, attention to the psychological aspects of the decision-making process becomes essential. Participative decision making has proved effective in achieving procedural fairness. Two-way communication helps dispel perceptual inequity. Provision for feedback contributes to a climate of open exchange. Moreover, engagement of overseas units pays dividends because employees who provide input into the decision-making process are more likely to support and implement the final results. Conversely, estrangement from the decision-making process can induce powerful resistance to change.17 Participation at the country level also opens the possibility of more-creative solutions.

3Com has processes for systematic worldwide input into decisions bearing on work-force policies. If a policy change is under consideration, 3Com executives notify HR managers worldwide. As the policy statement evolves, the managers evaluate its potential fit in their respective countries and raise any red flags about problems that might attend implementation. A couple of people in a region may be designated as the unit’s eyes and ears for a particular policy. For policies under development, 3Com designed an internal, password-protected Web site to facilitate dynamic and continuous dialogue. In evolving an inclusive process, the next logical step would be to assign primary responsibility for global-policy formulation to units outside the United States.

Clearly, a corporate global mind-set is not simply “all in the head.” Rather it requires supporting policies and practices. To formulate appropriately consistent policies, executives must assess and align structure, process and power tensions. Although any point on the grid presents a possible salutary response, work force management policies appear to call increasingly for an approach high in both consistency and responsiveness.

A Competitive Advantage

Many respondents considered a global mind-set to be a desirable state, believing that competitive advantage ensues from actions consistent with it. The literature reinforces the view that such actions can improve financial performance, employee commitment and receptivity to organizational change.18 Yet in every one of our sample companies, such a comprehensive perspective lagged the company’s global expansion.

IBM seemed to have made the greatest strides toward a global mind-set. In the 1960s, so rigid was its emphasis on global consistency that every employee received the same benefits regardless of need. The company even funded medical benefits in countries that guaranteed their citizens universal health coverage. Then, shaken by its early 1990s crisis, IBM embraced a more flexible approach, including global policy-development teams, worldwide knowledge networks and the IBM performance management system. In attempting to balance global with local concerns and inculcate a global mind-set, IBM executives have pushed many levers, but they report a gap they still need to close.

Because many U.S. executives regard globalization as the pursuit of standardized products through centralized decision making, they naturally favor global consistency over local responsiveness. Yet in their relentless rush toward consistency, they have not secured the cooperation of local constituents. Through a global mind-set, corporate decision-making processes become more permeable to ideas and influences from beyond the home country. As evidence of the mind-set, management must recognize when an issue calls for a locally adaptive response, a globally consistent response or a response featuring both elements. The third response is rapidly expanding its sphere. The corporate global mind-set is more than a catchphrase; it is a requirement for motivating a diverse and sprawling work force. The global mind-set offers the promise of a corporation energized and enhanced by all its employees.

References

1. See M.L. Maznevski and H.W. Lane, “Shaping the Global Mind-Set: Designing Educational Experiences for Effective Global Thinking and Action” in N. Boyacigiller, R. Goodman and M. Phillips, eds., “Teaching and Experiencing Cross-Cultural Management: Lessons From Master Teachers” (London: Routledge, in press). We have slightly modified Maznevski and Lane’s individual-level definition so that it refers instead to the company level.

2. See C.A. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution,” 2nd ed. (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998), and “The Myth of the Generic Manager: New Personal Competencies for New Management Roles,” California Management Review 40 (fall 1997): 92–116; V. Govindarajan and A.K. Gupta, “The Quest for Global Dominance: Transforming Global Presence Into Global Competitive Advantage” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001); and T.P. Murtha, S.A. Lenway and R.P. Bagozzi, “Global Mind-Sets and Cognitive Shift in a Complex Multinational Corporation,” Strategic Management Journal 19 (February 1998): 97–114.

3. G. Svensson, “ ‘Glocalization’ of Business Activities: A ‘Glocal Strategy’ Approach,” Management Decision 39 (2001): 6–18.

4. R.M. Kanter and T.D. Dretler, “Global Strategy and Its Impact on Local Operations: Lessons from Gillette Singapore,” Academy of Management Executive 12 (November 1998): 60–68.

5. N. Athanassiou and D. Nigh, “The Impact of the Top Management Team’s International Business Experience on the Firm’s Internationalization: Social Networks at Work,” Management International Review 4 (spring 2002): 157–181.

6. For example, Y.L. Doz and C.K. Prahalad, “The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision” (New York: Free Press, 1987); and C.K. Prahalad and K. Lieberthal, “The End of Corporate Imperialism,” Harvard Business Review 76 (July–August 1998): 68–79.

7. In an attempt to limit the variation induced by multiple country and industrial sectors, the research focused on U.S.-based high-technology companies, including most of the major companies in computer hardware, software and services as well as the telecommunications industry. The momentum and magnitude of this sector make it an attractive domain for exploring how companies face the challenge of managing a worldwide work force. Moreover, many of these companies are regarded as management trendsetters.

8. For example, J. Greenberg and R. Cropanzano, eds., “Advances in Organizational Justice” (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2001).

9. T.M. Begley and D.P. Boyd, “Articulating Corporate Values Through Human-Resource Policies,” Business Horizons 43 (July–August 2000): 8–12.

10. E. Yuen and H. Kee, “Headquarters, Host-Culture and Organizational Influences on HRM Policies and Practices,” Management International Review 33 (fall 1993): 361–383; and M.P. Kriger and E.E. Solomon, “Strategic Mind-Sets and Decision-Making Autonomy in U.S. and Japanese MNCs,” Management International Review 32 (fall 1992): 327–343.

11. R.S. Shuler, P.J. Dowling and H. De Cieri, “An Integrative Framework of Strategic International Human-Resource Management,” Journal of Management 19 (summer 1993): 419–460.

12. Bartlett, “Managing Across Borders”; R.E. Miles and C.C. Snow, “Fit, Failure and the Hall of Fame: How Companies Succeed or Fail” (New York: Free Press, 1994); J.C. Collins and J.I. Porras, “Built To Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies” (New York: HarperBusiness, 1994); and Greenberg, “Advances in Organizational Justice.”

13. E.C. Wenger and W.M. Snyder, “Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier,” Harvard Business Review 78 (January–February 2000): 139–145.

14. K. Moore and J. Birkinshaw, “Managing Knowledge in Global Service Firms: Centers of Excellence,” Academy of Management Executive 12 (November 1998): 81–92.

15. Collins and Porras, “Built To Last.”

16. P.A.L. Evans, “Management Development as Glue Technology,” Human Resource Planning 15 (1992): 85–105.

17. See, for example, W.C. Kim and R.A. Mauborgne, “Making Global Strategies Work,” Sloan Management Review 34 (spring 1993): 11–27.

18. K.L. Newman and S.D. Nollen, “Culture and Congruence: The Fit Between Management Practices and National Culture,” Journal of International Business Studies 27 (fall 1996): 753–779; S. Taylor and S. Beechler, “Human Resource Management System Integration and Adaptation in Multinational Companies,” in S. Prasad and R. Peterson, eds., “Advances in International Comparative Management” (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1993), 155–174; R. Gill and A. Wong, “The Cross-Cultural Transfer of Management Practices: The Case of Japanese Human Resource Management Practices in Singapore,” International Journal of Human Resource Management 9 (February 1998): 116–135; and B.L. Kirkman and D.L. Shapiro, “The Impact of Cultural Values on Employee Resistance to Teams: Toward a Model of Globalized Self-Managing Work Team Effectiveness,” Academy of Management Review 22 (July 1997): 730–757.