The Rhythm of Change

Topics

We are all familiar with the modern-day manager’s mantra that we live in times of great and constant change. Because the world is turbulent, it is said, and the competition is hyperturbulent, managers must take seriously the job of continually initiating and adjusting to change. Change, by definition, is good. Resistance to change is bad.

Might we suggest that you turn off the hype and look out the window? Do you notice anything out there resembling all that supposed change and turbulence? We perceive our environment to be in constant flux because we only notice the things that do change. We are not as keenly aware, however, of the vast majority of things that remain unchanged — the engine of the automobile you drive (basically the same as that used in Ford Motor Co.’s Model T), even the buttons on the shirt you wear (the same technology used by your grandparents). This, indeed, is a good thing, because prolonged and pervasive change means anarchy — and hardly anybody wants to live with that. Sure, important changes have been taking place recently, but the truth is that stability and continuity also form the basis of our experience. In fact, change has no meaning unless it is juxtaposed against continuity. Because many things remain stable, change has to be managed with a profound appreciation of stability. Accordingly, there are times when change is sensibly resisted; for example, when an organization should simply continue to pursue a perfectly good strategy. What’s needed is a framework whereby pragmatic, coherent approaches to thinking about change can be explored.

Dramatic, Systematic and Organic Change

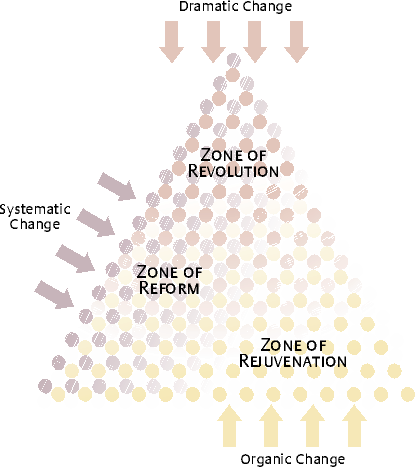

Today’s obsession with change focuses on that which is imposed dramatically from the “top.” This view should be tempered, however, by the realization that effective organizational change often emerges inadvertently (organic change) or develops in a more orderly fashion (systematic change). (See “The Change Triangle.”)

Dramatic change is frequently initiated in times of crisis or of great opportunity when power is concentrated and there is great slack to be leveraged (for example, in the sale of assets). It can range from rationalizing costs, restructuring the organization and repositioning strategy to reframing the organization’s mind-set and revitalizing its culture. Usually, a company’s leadership commands this dramatic change in the expectation of compliance by everyone else. Although this kind of initiative can be effective, it can also be misguided and engender covert resistance. For example, consider the case of Vivendi Universal. In a five-year buying spree in the late 1990s, former CEO Jean-Marie Messier borrowed heavily against Vivendi’s water-utility business, acquiring numerous telecommunications, media and entertainment firms, including Seagram Co.’s Universal Studios and the Universal Music Group, in an ill-fated attempt to build a vertically integrated media conglomerate. When the stock bubble burst, Vivendi’s market value plummeted, and Messier was fired. Seeing no synergistic benefit in these disparate holdings, his successor, Jean-René Foutou, is now selling off most of them.

Systematic change is slower, less ambitious, more focused, and more carefully constructed and sequenced than dramatic change. In a word, it is more orderly. Often it is promoted by staff groups and consultants who handle planning and organizational development. Over the years, many approaches to systematic change have appeared, including quality improvement, work reprogramming, benchmarking, strategic planning and so on. As the nature of these approaches suggests, systematic change draws heavily on technique and, in that sense, is change imported to the organization. But it can also be overly formalized and so stifle initiative in the organization.

Whereas dramatic change is usually driven by the formal leadership and systematic change is usually promoted by specialists, organic change tends to arise from the ranks without being formally managed. It often involves messy processes with vague labels like venturing, learning and politicking and is nurtured behind the scenes in the skunk works of big companies such as 3M Co. or Intel Corp. and in those near-legendary garage startups that spawned industry giants like Apple Computer Inc. and Dell Computer Corp.

The trouble is that the organic approach can be splintered and is itself anarchical. Groups may begin to work at cross-purposes and fight each other over resources. When informal groups indulge in experiential learning, narrowed competences can result if each focuses on promoting only what it knows best to serve its own interests.

The important thing to understand about organic change is that it is not systematically organized when it begins or dramatically consequential in its intentions, and it does not depend on managerial authority or specialized change agents. Indeed, it often proceeds as a challenge to that authority and those agents, sometimes in rather quirky ways. Yet its results can be dramatic. Clever leadership can, however, stimulate organic change by socializing the organization to prize it. Companies, such as 3M, Honda, Sony and Intel, have recognized that managerial support and network building can be the key to generating change initiatives at the grass-roots level.

In our view, neither dramatic nor systematic nor organic change works well in isolation. Dramatic change has to be balanced by order and engagement throughout the organization. Systematic approaches require leadership and, again, depend on broad engagement. And organic change, though perhaps the most natural of the three approaches, eventually must be manifested in a systematic way, supported by the leadership.

The Rhythm of Change

Throughout the years, we have acquired in-depth familiarity with many organizational change situations — some gleaned from our experiences as consultants or when working in managerial capacities ourselves, others as part of research projects to track the strategies actually realized by companies over many decades.1

Because dramatic change alone can be just drama, systematic change by itself can be deadening, and organic change without the other two can be chaotic, they must be combined or, more often, sequenced and paced over time, creating a rhythm of change. When functioning in a kind of dynamic symbiosis, dramatic change can instead provide impetus, systematic change can instill order, and organic change can generate enthusiasm.

We have seen this symbiosis arising in three main modes. Revolution is dramatic, but often comes from organic origins and later requires systematic consolidation. Reform is largely systematic, but has to stimulate the organic and can sometimes be driven by the dramatic. And rejuvenation is fundamentally organic, but usually must make use of the systematic, and its consequences can be inadvertently dramatic.2 In illustrating this framework, we cite older examples alongside newer ones, which helps us to make another crucial point: The problem with change is the present. That is, an obsession with the new tends to blind managers to the fact that the basic processes of change and continuity do not change. So older examples, because their consequences have settled, can be more insightful than newer ones.

Corporate Revolution

We associate revolution with dramatic acts that change a society. Yet many revolutions actually begin with small organic actions —a “tea party” in Boston or the storming of the Bastille in Paris (that released only a handful of prisoners!). These acts spark the drama; then leadership arises, but only if the conditions, organically, are right. Consider the following:

“The [American] Revolution was effected before the war commenced,” John Adams wrote. “The Revolution was in the hearts and minds of the people. … This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments and affections of the people was the real American Revolution.” A revolution without a prior reformation would collapse or become a totalitarian tyranny.3

Think of all the totalitarian tyrannies in today’s corporations —all the dramatic change devoid of organic underpinnings and lacking systematic support. The leader acts alone, heroically it seems, and everyone else is supposed to follow. Thus we get the great mergers (Daimler-Benz and Chrysler, AOL and Time Warner, Compaq and Hewlett-Packard), the grand strategies (Jean-Marie Messier at Vivendi, L. Dennis Kozlowski at Tyco) and the dramatic downsizings (“Chainsaw Al” Dunlap at Scott Paper Co. and Sunbeam Corp.). There are, however, two forms of revolution that can work.

Driven Revolution

To appreciate when leader-initiated revolution can work, consider the case of Steinberg, Inc., a major Canadian grocery chain whose strategies we tracked over 60 years. Entrepreneur Sam Steinberg propelled two major changes in 1933 and 1968, which despite their 35-year separation, were remarkably similar.

In 1933, one of the company’s eight stores “struck it bad,” as Steinberg phrased it, incurring “unacceptable” losses of $125 a week. He closed the store one Friday evening, converted it to self-service (a new concept for Montreal), changed its name, slashed its prices by 15–20%, printed handbills, stuffed them into neighborhood mailboxes and reopened on Monday morning. That certainly seems dramatic, but he did this in just a single store. Only when the changes proved successful did he convert the other stores — systematically. Then, in Steinberg’s words, “We grew like Topsy,” at least until the mid-1960s, when the company — then much larger with almost 200 stores — faced fierce competition. In 1968, the company initiated large, permanent, across-the-board price reductions, coupled with a complete shift in merchandising philosophy. It eliminated specials, games and gimmicks, and reduced service and advertising, returning to what it knew best. But these changes too began in one store before being allowed to spread to the rest of the operation, with enormous success.

Fomented Revolution

In their organic origins, corporate revolutions can also resemble the political ones of 18th-century America and France. For instance, organic changes helped to undermine established behaviors and induce new learning at Volkswagen AG, a company whose strategic evolution we have studied by looking back to the inception of its first automobile in 1934. In the 1960s, many middle managers at the company believed it had to move away from its reliance on the Beetle, but their consistent lobbying was to no avail. With the arrival of a new, deeply knowledgeable chief executive, however, that pent-up organic foment was catalyzed into revolution, and Volkswagen quickly began to produce more stylish, front-wheel-drive, water-cooled cars.

Such stories are, in fact, common. Organic changes infiltrate and bypass skeptical areas of the organization and, through gradual experimentation and persistent small victories, open up the system to really dramatic change.

Consolidating the Revolution

Revolutions must be consolidated: They have to get beyond the dramatic to the systematic and the organic. Companies are judged on the products and services they deliver, not on the changes they make. As the experiences of British Airways Plc show, there are better and worse ways to pace the consolidation of dramatic change.

In the late 1970s, British Airways was ranked among the worst air carriers for customer service and was losing money rapidly. By 1993, however, it had become Europe’s most profitable carrier and was benchmarked as a provider of world-class customer service. How did this occur? Upon his arrival in 1983, Colin Marshall, the new CEO, wasted no time in commanding dramatic change. His first two years were characterized by ambitious and rapid change: The workforce was downsized and assets were sold because of poor performance; in one 24-hour period, Marshall terminated 161 managers and executives.

Two years later, sensing that a slower, more tolerable rhythm would be appreciated, Marshall launched systematic consolidation through training programs that encouraged managers to enhance customer service. By 1985, the company opted for organic change to complement the systematic initiatives: Employees with proven interpersonal skills were asked to develop a “family” climate for customer-facing employees. In 1987, systematic and faster-paced reengineering of work processes was introduced, as BA invested heavily in information technology to build a new reservation system. Thus, BA was transformed into a profitable carrier with an enviable reputation for customer service.

In 1996, as British Airways was at its peak in profitability and customer service, Marshall stepped down and a new CEO, Bob Ayling, was appointed. Ayling anticipated higher competitive pressures in the long term and thus wanted to streamline the airline cost structure immediately. The business logic seemed to make sense, but the way he went about it backfired. Ayling suddenly announced dramatic change through major cost cutting and staff reductions on the same day when the company announced record profits. Most employees were shocked because they had not been informed, and the announcement’s timing and the magnitude of sacrifices demanded of them did little to win them over. Flight attendants went on strike. BA leadership fanned the fires of dissension by declaring the strike illegal and using intimidation tactics. In subsequent years, systematic efforts to boost low morale and declining customer service were treated with cynicism by employees. Eventually, Ayling resigned, as BA once again became an unprofitable airline with dismal customer service.

Clearly, corporate revolutions are not uniformly effective, and many times something else is called for.

Corporate Reform

Reform — by which we mean “re-forming” a social system in an orderly way — used to be favored in politics and in business. The carefully developed Marshall Plan, the subsequent growth of the European Community (now the European Union) and the successful redevelopment of postwar Japan are outstanding examples of change driven largely by systematic efforts. These are cases where the cumulative effects of the initiatives amounted to changes as massive as those of many full-fledged revolutions.

Planned Reform

In practice, systematic change must be realized organically, not only around conference tables where plans are hatched, but also in operations, where real things happen. Even strategies are not created in a formal planning process; so-called “strategic planning” is, in fact, usually strategic programming,4 which takes place throughout an organization in the minds and actions of creative individuals. This is the essence of planned reform. However, like a revolution that never advances beyond its drama, reform that becomes mired in procedures is equally useless. In one study of an airline, we found that an obsession with planning impeded strategic thinking. When operational planning takes precedence, everything can become too systematic.

Two variants of reform, though, are especially effective in stimulating organic change.

Educated Reform

Many organizations use systematic training and development programs to breed an atmosphere conducive to organic change, most notably General Electric Co.’s Work-Out process that had been launched to encourage frontline workers to improve workplace efficiency. Another interesting example described by Richard Pascale5 and his coauthors is that undertaken by the United States Army. Over a grueling 14-day period, an organizational unit of 3,000 to 4,000 people goes head to head with a competitor of like size in a highly realistic simulation, including desert tank battles and aircraft support. Six hundred instructors are involved, one for each person with managerial responsibility; they shadow their trainees through the 18-hour days. The debriefing event (or “After Action Review, where hardship and insight meet”) can be harassing, with officers often cowering under the intense scrutiny. But according to the commander of the exercise, it “has changed the Army dramatically. … It has instilled a discipline of relentlessly questioning everything we do.”

Energized Reform

Here the emphasis of the reform is to drive organic change directly. General Electric’s Six-Sigma efforts come to mind, as does kaizen (total quality management), used so successfully by Japanese companies like Toyota Motor Co.

While initially showing shades of revolution and later rejuvenation, Louis Gerstner’s changes at IBM Corp. might be best described as energized reform — steady and consistent. No great new vision or revolution emerged. The company simply returned to listening to customers and managing relationships, focusing once again on key business results, devolving more authority and accountability from staff groups to line managers and carefully reengineering work processes to reduce long-term costs.

Corporate Rejuvenation

Often, significant corporate change comes about largely, although not exclusively, as the result of organic efforts embedded deep within an organization. This corporate rejuvenation can come about in a variety of ways.

Inadvertent Rejuvenation

Organizations often learn by trying new things, by engaging in all kinds of messy little experiments. The best learners are those closest to the operations and the customers. Indeed, this is probably how most of the really interesting changes in business and even society happen. Sometimes a single, seemingly peripheral or even inadvertent initiative remakes an organization. This is not revolution, although the consequences may be revolutionary.

One of our favorite examples of this sort of inadvertent rejuvenation cum revolution is Pilkington Plc, a glass manufacturer based in St. Helens, England. Years ago, one of its engineers was doing the dishes at home, so the story goes, when he got an idea for a new way to make glass, by floating it on a bath of liquid tin. After seven years of experimentation (supported by the board) and 100,000 tons of wasted glass, he had yet to prove he could make soluble glass. As each problem was solved, a new one took its place. The engineer remained optimistic and persistent, the board remained remarkably patient, and both were rewarded with eventual success. Patents were granted, and the company licensed the process worldwide. A grass-roots, production-process redesign had transformed into a successful strategy, revolutionizing the company and its industry.

Imperative Rejuvenation

In one of our most intensive studies of change, a large telecommunications company under fierce global competition was losing market share and money rapidly. Seeking new ways to address customer needs and reduce costs, new leadership brought a wave of dramatic changes: a new executive team, a 25% downsizing, a wide array of consultants and all manner of big-change projects, including three restructurings in three years. (One of us closely studied 117 of these projects.) Only about one in five of the large change initiatives launched by their senior managers met with demonstrable success. At the same time, a host of smaller initiatives launched by middle management fared much better, with about four out of five producing good results. Whereas the dramatic revolutionary actions largely failed, the more organic initiatives sustained and revitalized the company well after the new leadership was gone.6

Steady Rejuvenation

Companies such as HP or 3M have been able to sustain their innovative capacities over long periods of time by finding a workable combination of steady organic change supported by systematic change. As Shona Brown and Kathleen Eisenhardt put it, balancing tensions between the organic and the systematic tends to keep an organization “on the edge of order and chaos” and so helps to sustain its innovative capability.7 Such organizations systematically invest in a wide variety of low-cost experiments to continuously probe new markets and technologies; they pace the rhythm of change to balance chaos and inertia by applying steady pressure on product-development cycles and market launches; and they maintain speed and flexibility by calibrating the size of their business units to avoid the chaos that is characteristic of too many small units and the inertia associated with most large bureaucracies. This kind of continuous innovation can be found not only in high-tech firms, but also in so-called staid academic institutions.

When, for example, one of us studied the realized strategies of McGill University between 1829 and 1980, he found neither evidence of anything faintly resembling a revolution in that century and a half nor any stage when many strategies were changing simultaneously. Although there was little deliberate overall strategic change — especially with regard to the essential missions of the university, namely, teaching and research — McGill was, in fact, changing all the time. Programs, courses and research projects were under constant revision and updated by the faculty. Of course, the university administration systematically facilitated the organic changes through budget allocations, facilities construction, new procedures for hiring and tenure and so on.

Although universities are unusual in many respects, they are akin to manufacturing corporations in an important way. While both organizations may tolerate occasional bursts of dramatic change, mostly they hum along, experiencing less-pervasive streams of small changes8 — here and there, organic and systematic — pursuing a process that Eric Abrahamson has labeled “dynamic stability.”9

Driven Rejuvenation

Rather than foment revolution, a leader can induce change by personal example or by recalibrating an organization’s culture to encourage its people to undertake organic initiatives. Perhaps the classic example of this is Mahatma Gandhi, the ultimate organic leader. Gandhi lived and functioned far from the centers of conventional power; he never sought election and never led by edict, but through example he inspired the Indian people to rise up and take control of their destiny. He did not drive dramatic change so much as foment popular rejuvenation.

Certainly few, if any, stories from business come close to matching that degree of poignancy, but there are many business leaders who do energize people with the palpable force of their authentic acts. Take Tsutomu Murai, who in 1982 became the new CEO of the then lackluster and beleaguered Japanese beer producer Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Murai spurred the development of the innovative Asahi Super Dry product that revolutionized Japanese drinking taste and Asahi’s fortunes by gently pushing a basic theme: He simply got the production and marketing people to talk to each other. Or consider Christian Blanc, the CEO whose first step toward revitalizing the Air France Group was to disclose that his compensation was 255th within the company — after which he took an additional 15% cut. Similarly, Roger Sant and Dennis Bakke of AES Corp., a global electricity company based in Arlington, Virginia, continually encourage frontline workers to expand their expertise and autonomy — not just by providing them with training, but also with the kind of sensitive strategic and financial information usually reserved only for senior managers. Such basic acts of conviction and faith can inspire rejuvenations tantamount to organic revolutions.10

DRAMATIC CHANGE MAKES for grand stories in the popular press, first about its promises and later about its often-dramatic collapses. Unlike the phoenix of mythology, which could rise from its own ashes but once every 500 years, companies cannot continue to rely solely upon the mythical promise of dramatic reemergence. This is not to argue that companies should abandon dramatic initiatives, but rather that lasting, effective change arises from the natural, rhythmic combination of organic and systematic change with the well-placed syncopation of dramatic transformation. The world continues to move ahead in small steps, punctuated by the occasional big one — just as it always has. It is now time to manage change with an appreciation for continuity.

References

1. H. Mintzberg, “Crafting Strategy,” Harvard Business Review 65 (July–August 1987): 66–75.

2. S.J. Mezias and M.A. Glynn, “The 3 Faces of Corporate Renewal: Institution, Revolution and Evolution,” Strategic Management Journal 14 (February 1993): 77–101. Evolution is similar to our rejuvenation, except that it is described as working within the rules; revolution disregards or breaks the rules and so is closer to what we call organic change; and institution is akin to our reform.

3. S.D. Alinsky, “Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals” (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), xxii.

4. H. Mintzberg, “The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning” (New York: Free Press, 1994).

5. R. Pascale, M. Millemann and L. Gioja, “Changing the Way We Change,” Harvard Business Review 75 (November–December 1997): 126–139.

6. Q.N. Huy, “Emotional Balancing of Organizational Continuity and Radical Change: The Contribution of Middle Managers,” Administrative Science Quarterly 47 (March 2002): 31–69.

7. S.L. Brown and K.M. Eisenhardt, “Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

8. D. Miller “Organizations: A Quantum View” (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1984).

9. E. Abrahamson, “Change Without Pain,” Harvard Business Review 78 (July–August 2000): 75–79.

10. Q.N. Huy, “Time, Temporal Capability and Change,” Academy of Management Review 26 (October 2001): 601–623.

Comment (1)

Nelson Caller