Three Ways to Sell Value in B2B Markets

Value-based selling can boost margins and competitiveness, but vendors must first advance beyond the prevailing one-size-fits-all approach.

Image courtesy of Dan Page/theispot.com

The ability to quantify and communicate value in business-to-business (B2B) sales is more important than ever. As customers face pressure to reduce costs while maintaining profitability, and more competitors are digitally enhancing or “servitizing” their offerings, value-based selling (VBS) has become critical in B2B markets.1 Yet when it comes to turning the idea into action, many companies seem to stumble.2

The key challenges of VBS often stem from the confusion and uncertainty about the actual value salespeople are supposed to sell, the outcomes they are supposed to price, and the risks and responsibilities the seller and buyer are supposed to share.3 While current literature considers VBS to be essentially a one-size-fits-all approach to sales, it leaves managers clueless about how to apply it in different situations. This is particularly acute in B2B markets, where vendors need different capabilities depending on whether they are selling high-value products, value-intensive services, or performance-based solutions.4

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

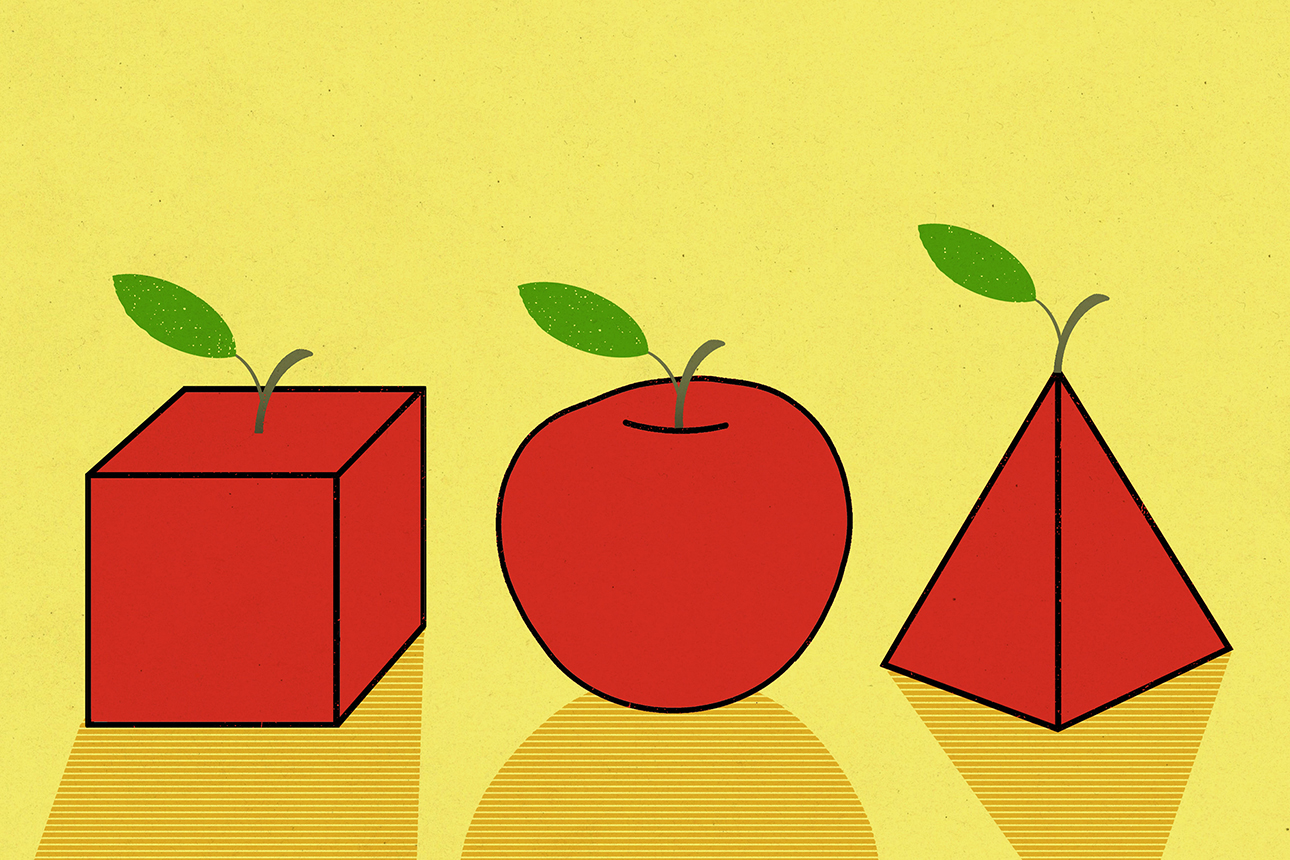

Based on our decade-plus of field research with more than 70 companies in a wide range of B2B industries, we suggest that rather than viewing VBS as a single strategy, vendors should choose from three different approaches. Our findings suggest that vendors can adopt either a product-centric, customer process-centric, or performance-centric VBS approach. In this article, we highlight the key characteristics, requirements, and challenges of each option and provide guidance on how to choose the right approach based on the circumstances.

The Key Capabilities of VBS

VBS is based on demonstrating and documenting the monetary worth of the economic, technical, service, and social benefits a specific customer receives in exchange for the price that customer pays.

References

1. A. Hinterhuber and T.C. Snelgrove, eds., “Value First Then Price” (London: Routledge, 2017); M. Bertini and O. Koenigsberg, “Competing on Customer Outcomes,” MIT Sloan Management Review 62, no. 1 (fall 2020): 78-84; and J. Keränen, A. Salonen, and H. Terho, “Opportunities for Value-Based Selling in an Economic Crisis: Managerial Insights From Firm Boundary Theory,” Industrial Marketing Management 88 (July 2020): 389-395.

2. H. Terho, A. Eggert, W. Ulaga, et al., “Selling Value in Business Markets: Individual and Organizational Factors for Turning the Idea Into Action,” Industrial Marketing Management 66 (October 2017): 42-55.

3. W. Ulaga and J.M. Loveland, “Transitioning From Product to Service-Led Growth in Manufacturing Firms: Emergent Challenges in Selecting and Managing the Industrial Sales Force,” Industrial Marketing Management 43, no. 1 (January 2014): 113-125.

4. W. Ulaga and W.J. Reinartz, “Hybrid Offerings: How Manufacturing Firms Combine Goods and Services Successfully,” Journal of Marketing 75, no. 6 (November 2011): 5-23.

5. J.C. Anderson, J.A. Narus, and W. Van Rossum, “Customer Value Propositions in Business Markets,” Harvard Business Review 84, no. 3 (March 2006): 90-99.

6. J.C. Anderson, N. Kumar, and J.A. Narus, “Value Merchants: Demonstrating and Documenting Superior Customer Value in Business Markets” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007); K. Storbacka, “A Solution Business Model: Capabilities and Management Practices for Integrated Solutions,” Industrial Marketing Management 40, no. 5 (July 2011): 699-711; and H. Terho, A. Haas, A. Eggert, et al., “‘It’s Almost Like Taking the Sales Out of Selling’: Towards a Conceptualization of Value-Based Selling in Business Markets,” Industrial Marketing Management 41, no. 1 (January 2012): 174-185.