Winning the Last Mile of E-Commerce

Topics

As the holiday season drew near, e-commerce retailers were either working anxiously to get their in-house processes ready or were double-checking with partners and service providers on order-fulfillment operations. Fears of revisiting the previous year’s fulfillment problems hounded them during their preparations for the projected high sales of Christmas 2000.1 “This is the season when the last mile will be the most crucial element of e-business,” one observer declared. “Sellers who come up with creative ways to deliver will secure enormous consumer loyalty.”2 What went wrong the preceding year? Online sales were at an all-time high in 1999, but many e-tailers found themselves unable to make timely, cost-effective deliveries. Late deliveries, broken promises and unmet expectations left both consumers and investors dissatisfied.3 In part because of that disappointment, stock prices plunged. E-tailers simply had not had operational processes capable of filling customers’ orders. By 2000, many still did not.4

It is true that e-commerce has improved the efficiency of placing orders. Trading partners communicate, coordinate, share information and manage inventory better as well. But in the future, e-businesses that can deliver the goods and services at a reasonable cost will have the edge. Order fulfillment can be the most expensive and critical operation for both the online and offline businesses of companies engaged in e-commerce. The ability to fulfill and deliver orders on time could determine an e-tailer’s success.

A few companies have come up with innovative ways to apply order-fulfillment strategies. The secret lies in making good use of information and leveraging existing resources to coordinate order-fulfillment activities. The principles are not new, but Internet technologies enable them to be applied in new and expanded ways.

E-Fulfillment Concepts

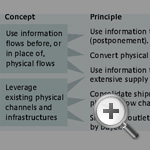

The two core concepts for making e-fulfillment efficient are: First, make more use of information flows than physical flows and, second, capitalize on current physical pipelines and infrastructures as much as possible for the last mile of delivery. The core concepts are tied to five strategies: logistics postponement, dematerialization, resource exchange, leveraged shipments and the clicks-and-mortar model. (See “From Concepts to Strategies.”)

From Concepts to Strategies

References

1. Online shopping for the 2000 holiday season was expected to jump by 80%, but according to the Web site BizRate.com, it rose by only about 60%.

2. E. Neuborne, “E-Tailers, Deliver or Die,” Business Week, Oct. 23, 2000, 16.

3. Sears found out after the Christmas season that many of its online orders were never registered within the company’s databases and hence never were filled. Toys “R” Us realized it could not deliver all its online orders before Christmas. It closed down its Web site, and three days before Christmas it issued $100 gift certificates to customers whose deliveries would be late. The same year, in a study that Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) dubbed the “e-Santa Study,” the firm’s consultants experimented with placing orders online and found that for most e-tailers, about 50% or more of the orders were shipped late.

4. An Accenture study of U.S. e-fulfillment in December 2000 found that 67% of deliveries were not received as ordered; 12% were not received in time for Christmas.

5. For an introduction to the concept of postponement, see E. Feitzinger and H.L. Lee, “Mass Customization at Hewlett-Packard: The Power of Postponement,” Harvard Business Review 75 (January–February 1997): 116–121; and H.L. Lee, C. Billington and B. Carter, “Hewlett-Packard Gains Control of Inventory and Service Through Design for Localization,” Interface 23 (July–August 1993): 1–11.

6. Details can be found in D.F. Pyke, M.E. Johnson and P. Desmond, “eFulfillment — It’s Harder Than It Looks,” Supply Chain Management Review 5 (January–February 2001): 26–32. Using the furniture industry as an example, the article also does a good job of describing the challenges of e-fulfillment.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

A thorough discussion of e-fulfillment issues can be found in David Anderson and Hau Lee’s “The Internet-Enabled Supply Chain: From the First Click to the Last Mile,” in the second volume of a 2000 Montgomery Research publication called “Achieving Supply Chain Excellence Through Technology.” The same volume contains many examples of how companies from different industries wrestle with fulfillment. Readers also may find useful David F. Pyke, M. Eric Johnson and P. Desmond’s “eFulfillment: It’s Harder Than It Looks” and Laura R. Kopczak’s “Designing Supply Chains for the Clicks-and-Mortar Economy” — both in the January–February 2001 Supply Chain Management Review. The Web site www.scmr.com carries interesting stories about how different companies deal with similar challenges. The Stanford Global Supply Chain Management Forum’s Web site, www.stanford.edu/group/scforum/, gives periodic updates on new developments in the field. Accenture’s study of Christmas e-fulfillment may be found at www.accenture.com, and the magazine Inbound Logistics is recommended for the latest news on logistics innovations.

Comment (1)

James Hendley