Orchestrating Workforce Ecosystems

Strategically Managing Work Across and Beyond Organizational Boundaries

Executive Summary

Confronting the challenges of intentionally leading and coordinating workforce ecosystems — what we call orchestrating workforce ecosystems — is at the heart of this report. This issue is especially timely given the ongoing workforce shifts brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, shifting worker preferences, and the changing nature of work.

This year’s research shows that orchestrating a workforce ecosystem is a multifaceted effort that involves integration among many business functions. In mature legacy organizations in particular, we see companies changing basic management practices around how they access, engage, and develop workers; we see leaders adapting to a changing workforce where they have more contributors but less control. In some cases, we see upwards of 30%-50% of an organization composed of contingent workers, and organizations increasingly relying on third parties to deliver some of their most essential services. With laws preventing traditional performance management for contingent workers, and with companies increasingly relying on arms-length contracting for critical services, some leaders have limited management options with a large percentage of their workers.1 We see executives often struggling to deal with a range of cultural issues as well: How far should they go to include external contributors in existing corporate culture? To what extent do diversity, equity, and inclusion principles and practices apply to external workers?

Our research shows that companies that are most intentionally orchestrating their workforce ecosystems have five common characteristics. They are far more likely than other organizations to:

- Closely coordinate cross-functional management of internal and external workers.

- Hire and engage the internal and external talent they need.

- Support managers seeking to hire external workers.

- Have leadership that understands how to allocate work for internal and external contributors.

- Align their workforce approach with their business strategy.

One thing our research makes clear: Leaders who view their workforce as an ecosystem structure tend to think differently about, and act differently toward, their workforce than leaders who view their workforce strictly in terms of hired (usually full-time) employees. What’s more, senior leaders and managers of functional areas report seeing the need and opportunities to work together in new ways.

This report marks the third year MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte have jointly explored the future of the workforce. Last year’s report proposed the workforce ecosystem as a structure that captures an organization’s engagement with a broad range of interdependent workers, including freelancers, gig workers, long-term contractors, third parties, and professional services organizations, in addition to traditional employees.

In this year’s report, we dive more deeply into the topic of orchestrating workforce ecosystems. Our findings reflect significant shifts in management practices, technology enablers, integration architectures, and leadership approaches. Based on interviews with 19 executives and thought leaders — a group that includes senior leadership, human resources, procurement, finance, IT, and business unit leaders — we offer several practical considerations for the functions primarily affected by a shift to workforce ecosystems.

Introduction

British multinational consumer goods company Unilever owns more than 400 brands that encompass food and beverages, vitamins and beauty products, and household wares and cleaning agents. The nearly century-old organization employs more than 150,000 people worldwide, but Jeroen Wels, executive vice president, human resources, estimates that the outer core of Unilever’s workforce — people, third parties, and agencies — numbers around 3 million. Wels says that he has lately come to realize that “you have responsibility for the inner and the outer cores. If you want to build more fluidity, you need to understand where those people sit and how they work with you.

“Most companies know pretty well how to manage their internal workforce,” Wels continues, but he is considering how to apply that knowledge to the company’s vast array of external contributors. “It’s become even more important to know about the external workforce and what contributions they could make,” he says. “So you also want to digitize data and insights around the external workforce and how you can manage friction points between the inner and outer cores. For me, it is one of the holy grails to drive productivity for growth in the future.”

At Fortune 500 company MetLife, chief human resources officer Susan Podlogar is also confronting the challenges of managing a large, multifaceted workforce ecosystem. In addition to its base of employees, the 154-year-old company, which provides insurance, annuities, and employee benefits programs, partners with a wide variety of contingent workers and external third-party firms, such as software and app developers.

“There is a very clear definition of what an employee is, but what is a ‘workforce’? It’s a broader concept; how do you pull down some of the barriers that exist to manage it as one cohesive group?” Podlogar asks. In addition to legal and regulatory issues, she notes that the day-to-day experiences of external workers are another concern. “How do you make sure they’re connected to your company’s purpose? People have a choice, and we want to make this experience the best one. We make sure we have the right trust, support, and development for them. It’s a challenge and an opportunity.”

We surveyed 4,078 managers and interviewed 19 executives and thought leaders to understand how businesses around the world, including Unilever and MetLife, are handling the challenges of orchestrating workforce ecosystems.

It’s increasingly clear that orchestrating workforce ecosystems requires a new set of management practices, leadership approaches, and other changes. The move from managing employees to orchestrating a workforce ecosystem is not a subtle shift. Leaders who are actively making this transition are not only thinking differently about their workforces and about how work should be accomplished but also altering their behaviors accordingly.

On the basis of our global survey and executive and management interviews, we offer specific guidance about how leaders can begin making this transition to orchestrating workforce ecosystems.

This year’s report builds upon previous research from MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte that introduced workforce ecosystems as a structure that aligns business and workforce strategies. This report highlights organizations that are already on their way to orchestrating their workforce ecosystems. Using our survey data, we created a workforce ecosystem orchestration index that recognizes organizations that are, to varying degrees, intentionally leading and managing workforce ecosystems.

Organizations with the highest scores on this workforce ecosystem orchestration index have several notable attributes. They are more likely to closely coordinate cross-functional management of internal and external workers and third-party organizations; hire and engage the internal and external talent they need; support managers seeking to hire external workers and engage with external collaborators; have leadership that understands how to allocate work for internal and external workers and collaborators; and align their workforce approach with their business strategy.

Drawing on our qualitative and quantitative research, this report presents a new approach to how senior leaders and managers across an organization can work together to more effectively lead, integrate, and manage their entire workforce, especially when that workforce includes many interconnected, and often interdependent, contributors of various types.

Section 1: Workforce Ecosystems — a New Reality

Multiple sources cite organizations’ growing dependence on temporary, part-time, contract, and other types of employment arrangements.2 Many companies are also increasing their dependence on external firms to create or add value to existing products and services. When Amazon built its transportation division, Amazon Logistics, the company didn’t hire drivers. Instead, it formed partnerships with independent delivery companies.3 Amazon was following a playbook that many companies are deploying: using networks of small partners to provide critical workforce contributors.

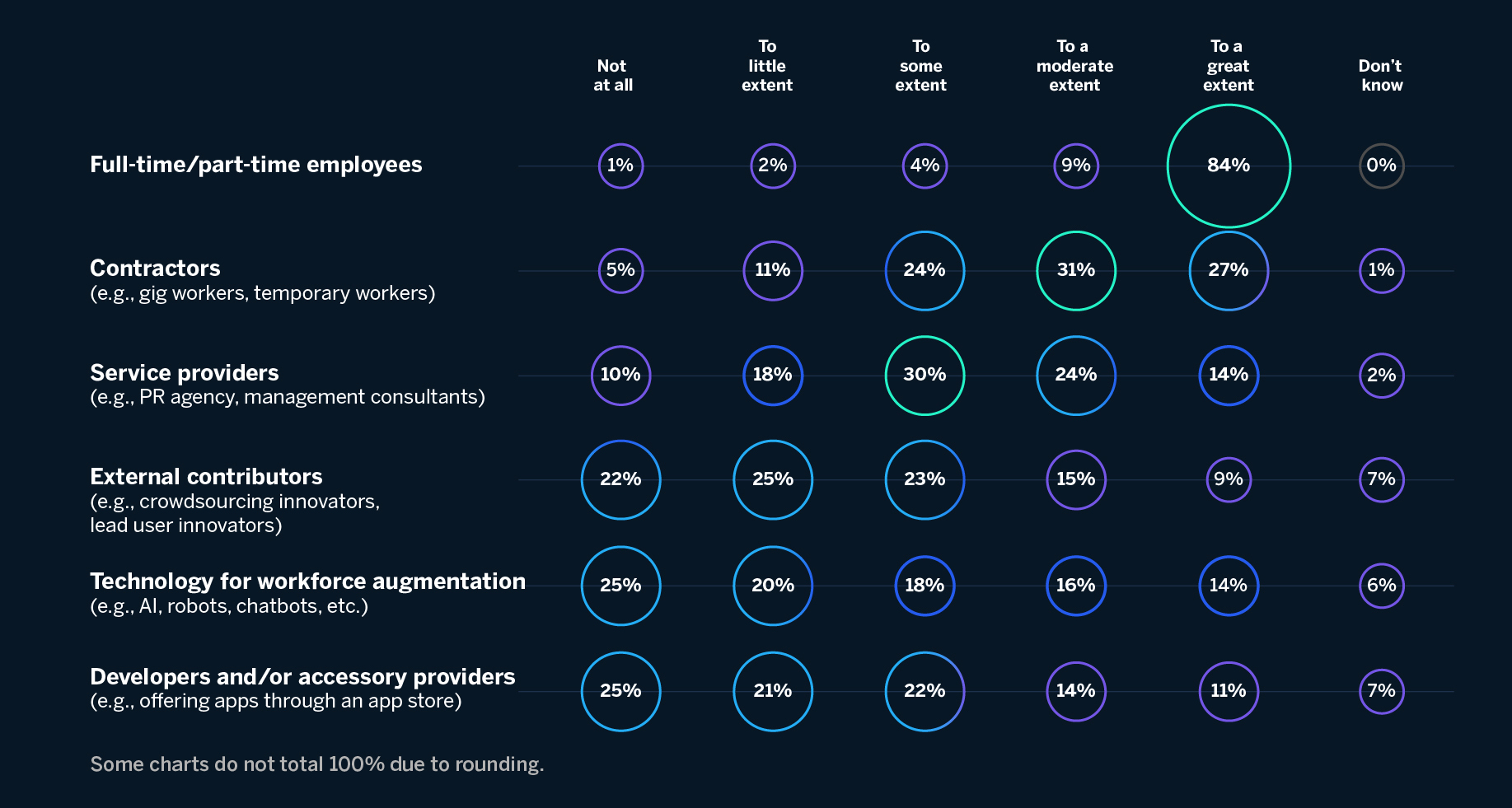

These trends appear to be having an effect on how managers perceive their workforce. Our global survey found that 93% of managers in companies around the world count some external workers to be part of their workforce. In the past two years, we have interviewed more than 50 executives: Without exception, they all affirmed that their workforce can no longer be defined strictly in terms of hired employees. For them, work is performed by many types of workers both inside and outside the enterprise, including third-party organizations. These contributors are sometimes directly employed by or contracted with the organization. In other cases, they may be complementors not directly engaged by the organization: These individuals or companies (app developers, for example) create products and services that work with an organization’s products (such as apps that consumers can download to their smartphones).

An Expansive View of the Workforce

Leaders are thinking expansively about who or what constitutes their overall workforce. Robert Gibbs, mission support director at NASA, explains that the agency has a broad and inclusive view of its workforce. “NASA is about one-third U.S. federal employees — the traditional definition of the workforce in the federal government — and two-thirds contractors. But the way we look at it is that these are all NASA employees. In that external two-thirds, we also have 150 international partnerships and 700 commercial partnerships. We do a lot of work across a lot of different spheres, and we try and make sure that we leverage the talents across this nontraditional definition of workforce to the best of our ability.”

Dror Gurevich, CEO of Velocity Career Labs and Velocity Network Foundation, organizations that deploy blockchain for career credentialing, has a wide-ranging view of the workforce. “Anyone that works for someone — that’s the workforce,” he says. “It’s that broad. It involves full time, part time, portfolio careers, gig work, contingent work, freelancing, contracting, subcontracting — everyone that is involved in doing work.” Gurevich echoed the perspective we heard from all of the executives we interviewed: An employee-only conception of the workforce is a thing of the past.

We define a workforce ecosystem as a structure focused on value creation for an organization. This structure encompasses actors, from within the organization and beyond, working to pursue both individual and collective goals, and includes interdependencies and complementarities among the participants.

Lion, a Japanese manufacturer, has introduced a side-job system in which it encourages employees to spend time working outside the company. This program enhances employees’ motivation to work and reflects a broad definition of what it means to be an employee of Lion. Daidoji Yoshihisa, general leader of Lion’s Human Resources Development Center, explains, “We still have progress to make, but we’re eager to expand side jobs in the future for our businesses.”

Former IBM chief human resources officer Diane Gherson, now a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School, emphasizes technology in her sweeping definition. “The workforce is made up of employees, but it’s also made up of contractors and outsourcing organizations and robots,” she says. “And robots are an increasingly large portion of the workforce. They are taking on more and more tasks and working directly with leadership and with employees on issues that, prior, real people were working on.” These technologies, alongside humans and contributing organizations, build a web of interconnected participants working together in an ecosystem structure.

Orchestration

Orchestration has many meanings, from the specific arrangement of music for a symphony to coordinating groups of participants. Orchestrating, in the sense that we use it in this report, involves coordinating discrete participants to create an aligned effort toward meeting organizational (and individual) objectives. In their 2020 book No Rules Rules (Penguin Press), Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer make a helpful distinction between conducting a symphony orchestra, which relies heavily on sheet music and established roles, and building a jazz band, which typically engages in a lot of improvisation. While there are times when workforce ecosystems may require more rigorous and prescribed conducting akin to an orchestra’s (for example, in dangerous or life-threatening situations that require the utmost safety), there are also plenty of occasions when creativity and innovation are most essential and a jazz band may be a better analogy. In both instances, however, orchestration allows the musicians to produce inspiring music. For workforce ecosystems, orchestrating the participants enables the organization to effectively achieve its strategic objectives.

Intentionally Orchestrating Both Internal and External Workforce Participants

Uniting an expansive view of the workforce with its holistic management is a key challenge for many when orchestrating a workforce ecosystem. Indeed, most organizations today manage employees and external contributors separately, in different areas of the business. By analogy, it would be inconceivable for a company to run multiple customer relationship management systems or multiple supply chains in parallel with few points of intersection. And yet it’s not unusual for different parts of a company to manage different parts of the workforce without much alignment: Think human resources for employees, procurement for contractors, and strategic business development for external organizations.

Nike board member Cathy Benko affirms that in most cases, no single entity bears responsibility for the entire diverse portfolio. “A business unit leader’s job is just to get the work done,” she says. “It’s not their job to figure out how they develop all the skills needed for all of the players sustainably over time. Nobody owns that. The project guy doesn’t own it. HR doesn’t own it. Accounts payable doesn’t own it. Who owns it?” Creating the infrastructure and processes to support effective management of both internal and external contributors requires a multifaceted approach that can be complex and labor-intensive.

Nevertheless, organizations increasingly recognize the need to orchestrate their workforce ecosystems with more intention. Seventy-four percent of our survey respondents believe that effective management of external workers is critical to their success, suggesting broad agreement that there’s a connection between managing a workforce ecosystem and achieving desired business outcomes. As Dave Ulrich, Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan and cofounder and principal of HR consulting firm The RBL Group, says, “You’ve got to build work systems for people, whether they’re full time, part time, or outside. You still need to think about positive performance management with accountability for both results and processes.”

Swiss global health care company Novartis is beginning to take a more deliberate approach to managing external workers as it increases its dependence on them. “In the last 12 to 18 months, we’ve focused on managing the external workforce more intentionally,” says Markus Graf, the company’s vice president, HR, and global head of talent. “If you ask me how I see things evolving, we will manage our external workforce even more actively, not only to attract labor, but also for access to skills that we may not have enough of internally. It’s becoming even more important in tech-related work, where skilled talent is less inclined to join a traditional workforce.” For Novartis, managing its access to external workers is as important as managing the workers themselves.

Novartis is not alone in wrestling with how to manage the entire workforce ecosystem. While roughly three-quarters of survey respondents believe that managing external workers is critical to business success, a smaller proportion (58%) affirm that their organization has in fact an integrated approach to managing internal and external contributors. And far fewer (30%) say that their organization is sufficiently preparing to manage a workforce that will rely more on external contributors. (See Figure 1.)

One challenge is the persistence of legacy practices and mindsets. MetLife’s Podlogar advocates for a fundamental mindset shift “from what the ‘internal we’ can deliver to what the ‘collective we’ can accomplish. That enables you to explore new frontiers for meeting customer needs, accelerating growth, and having meaningful work. You can get a broader outcome because you’re then using all the resources at your fingertips.” Orchestrating a workforce ecosystem may require leaders to change their mindsets as well as their behaviors.

Unilever’s Wels agrees that a shift in thinking is necessary. “You galvanize the leadership around a bigger goal than just managing your workforce internally,” he says. “That helps enormously to change the mindset of leaders, because then you can talk about, ‘OK, we want to skill up our people internally and externally as well. We want to create a more flexible and agile organization.’”

Of course, it’s not only fixed mindsets that are getting in the way. Andrew Saidy, vice president of global talent at Ubisoft, notes that in some countries, legal and regulatory requirements oblige companies to rethink workforce ecosystem management. “I’ll give you the example of the U.K.,” he says. “A third-party worker is not an employee of your company, so a manager cannot directly give them feedback on their performance or give them a warning. That creates unique challenges for performance management.” A workforce ecosystem approach expands on legacy management practices built for (and around) employees, but it can also add complexities posed by variations across geographies and regulatory environments.

Organizational Culture in Workforce Ecosystems

As organizations increase their reliance on a range of external contributors, they are exploring the extent to which those contributors can and should be included in their organization’s culture. Gherson notes that this is a pressing workforce topic for organizations to address: “A big issue in the United States is, how do you control your culture when more and more of your work is done by people who are not part of your value system and culture?” Our survey results suggest that for many, the answer is to more intentionally incorporate those people into the culture. A strong majority of survey respondents (80%) believe that it is important for external workers to participate in the organization’s culture.

Some of our interviewees note that the question of including external workers in an organization’s culture must be considered from the perspective of the final customer. Michael Smith, CEO of global talent solutions provider Randstad Sourceright, points out that customers don’t differentiate between full-time workers and contractors. “Our customers don’t perceive the contingent workforce to be hired help,” he says. “They perceive them to be a reflection of our brand.” In Smith’s framing, every person representing an organization should be aligned with its cultural norms and reflect its espoused values.

Achieving this alignment is not easy. For one thing, there are legal and regulatory hurdles and risks inherent in embedding external workers too deeply in internal culture. In addition, external workers aren’t always that interested in participating. PlanOmatic cofounder and CEO Kori Covrigaru recalls that efforts to involve the real estate photography company’s contractors in its culture “fizzled.”

“Typically, contractors will have multiple gigs going on,” Covrigaru points out. “They are their own brand; they are their own culture. Trying to get buy-in from people who may be here one, two days a week was difficult.”

Only 33% of our survey respondents report that their organization includes external contributors when measuring the impact of DEI initiatives.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

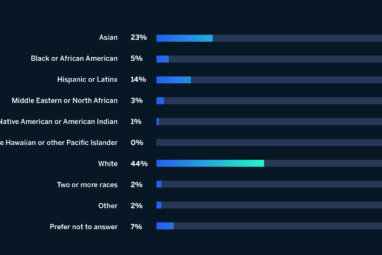

Some of the opportunities and challenges of workforce ecosystems can be captured through the lens of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. The prevailing narrative is that organizations are more actively measuring and advancing DEI outcomes. But only 33% of our survey respondents report that their organization includes external contributors when measuring the impact of DEI initiatives. Given that external contributors constitute a significant and growing proportion of many workforces, this data point suggests that many organizations’ DEI numbers may be misleading within the context of their entire workforce ecosystem.

Having a diverse base of employees is less meaningful if that base represents a shrinking percentage of the overall workforce ecosystem. Having equity among a base of employees is less meaningful if the base of employees represents a diminishing percentage of the overall workforce and unfair treatment (such as pay inequity) exists across the overall workforce ecosystem. The need to address DEI issues across the workforce ecosystem is, increasingly, on organizations’ radars. Smith notes that two years ago, few of Randstad Sourceright’s clients were thinking about DEI beyond their employees. Now, he says, most clients want to know “how to ensure that the work we’re doing on the contingent workforce is aligned with the goals we have with our permanent organization.” More executives are exploring how to apply their organization’s principles and values across their entire workforce ecosystem.

Similarly, as Novartis begins to manage its external workers, the company intends to measure the diversity of its external workforce, despite the difficulties of doing so. “We started off with a focus on DEI internally,” Graf says. “Once we manage the external workforce more actively, we will also look through the lens of DEI on the external workforce. Right now, it’s a challenge of how much data we have and how easy it is to capture information. We’ve been struggling to capture ethnicity in a number of countries because we’re not legally allowed to. But our desire to manage DEI in the context of external partners is a given.”

Another challenge is presented by the fact that external workers often cycle through organizations for short-term gigs. “Inclusion is hard, but it drives better outcomes,” MetLife’s Podlogar reflects. “Inclusion is not just bringing all these people together, but it’s fundamentally understanding them — their backgrounds, their experiences, how they can contribute in different ways — and bringing that into your work and your outcomes. That can be hard to sustain when you’re bringing people in and out quickly.” In dynamic workforce ecosystems, executives have had to rethink their approach to DEI performance. This issue is further complicated when an organization’s workforce ecosystem includes separate business units with their own DEI agendas and initiatives.

Section 2: Confronting the Orchestration Challenge

Organizations are just beginning to grapple with the challenges of orchestrating their workforce ecosystems. We wanted to determine what, if anything, differentiates those enterprises that are further along in the process. To that end, we created an orchestration index based on survey responses that reflect different levels of workforce ecosystem orchestration. Three criteria were used: (1) a vision of the workforce that includes both internal and external contributors, (2) the extent to which the management of internal and external workers is integrated, and (3) the degree of preparedness for managing a workforce made up of more external providers. The three measures were summed into a single score. We then divided respondents into three groups based on their scores.

Those in the highest-scoring group are the Intentional Orchestrators. These companies view their workforces in terms of employees and external contributors; they are pursuing an integrated approach to managing both internal and external workers; and they are preparing to manage a future workforce increasingly reliant on more external workers. We refer to the other groups as Partial Orchestrators and Non-Orchestrators. (see “About the Research,” for the precise questions that we used, how we divided the scores into three categories, and the breakdown of how many respondents fell into the three categories.) (See Figure 2.)

Intentional Orchestrators have five distinctive characteristics, and we offer a detailed description of each characteristic in this section.

1. Intentional Orchestrators tend to closely coordinate cross-functional management of internal and external workers.

The Intentional Orchestrators are far more likely than other respondents to affirm that their organizations coordinate the cross-functional management of their ecosystem. Only 38% of respondents overall report that their organization currently coordinates managing internal employees and external contributors across functions. At 66%, Intentional Orchestrators are almost twice as likely as the Partial Orchestrators (35%) and more than four times as likely (14%) as the Non-Orchestrators to report such coordination. (See Figure 3.)

As with much of workforce ecosystem management, this process is in the nascent stages. Novartis, for instance, is working toward integrating the management of its 100,000-plus internal workers and 50,000 external workers — in its case, under the umbrella of the People & Organization function. “As you want to manage workforce more deliberately, and externally as well, I think the HR team will play a more active role,” Graf predicts. “We currently see joint responsibility between talent management and the talent acquisition organization. So it's not yet one unit, but the vision is to get there as we start to embrace this workforce strategy in the organizational setup. We see the value in investing into our HR teams to manage the external workforce even more purposefully.”

2. Intentional Orchestrators are more likely to hire and engage the internal and external talent they need.

Seventy-nine percent of the Intentional Orchestrators agree that they will be able to hire the employees their organization needs to accomplish its strategic objectives over the next 18-24 months; only 34% of the Non-Orchestrators agree with the statement.

When it comes to external contributors, the numbers are similar: Eighty percent of the Intentional Orchestrators affirm that their organization will be able to engage the external contributors it needs to accomplish its strategic objectives, while only 32% of the Non-Orchestrators agree with the statement. (See Figure 4.)

Our qualitative research suggests that organizations are beginning to tackle these issues more strategically. Randstad Sourceright’s Smith, for instance, describes a client that created a cross-functional “workforce of the future” task force to coordinate the hiring of internal and external workers. “It’s their job to break down the traditional silos of buying behavior and operate in a much more conjoined fashion,” he explains. “Typically, HR and talent acquisition would own permanent hiring, procurement would own contingent hiring, IT projects would be done by line-of-business heads, etc. And what that group is designed to do is say, ‘How do we work together to get a better understanding of leveraging the ecosystem in a more efficient way?’ They’ve been able to bring down their time to hire and increase their quality of hire when they share that knowledge.”

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, chief innovation officer at the staffing firm ManpowerGroup, agrees that clients are thinking more strategically about staffing. “They’re asking more integrated questions — not just, ‘Hey, find me a bunch of IT consultants or contractors or customer service operators now,’ but more, ‘How do I need to think or plan for the future configuration of my business?’ That includes the question of, ‘How many people would actually be full-time employees?’ versus, in an outsourcing model, ‘What will be the composition, and what do I need to plan for?’” In an intentionally orchestrated workforce ecosystem, questions about what capabilities a company needs are framed in terms of how the company will access and engage those capabilities, wherever they reside.

Companies that are the most intentional about orchestrating their workforce ecosystem typically develop a wide range of tactics, systems, and processes for engaging the workers they need. At some companies, engaging external workers is on the rise, while at others, such as transportation logistics company DHL, the focus has been on strategic recruitment and flexibility for employees within the organization. “We need to manage all the different levels of the workforce in order to ensure that we have a sustainable pool of labor moving forward,” says Meredith Wellard, DHL’s vice president of group learning, talent, and HR platforms. To that end, DHL has created a talent marketplace to engage and promote internal talent. This skills-based marketplace is open and employee-driven, and it creates more opportunities for employees within the company.

Some orchestrating tactics are designed exclusively for engaging employees; others are exclusively for external contributors. And there is growing interest in tactics that engage a blend of internal and external contributors, such as opening internal marketplaces to external contributors.

3. Intentional Orchestrators are more likely to support managers seeking to hire external workers.

The vast majority of Intentional Orchestrators (91%) say that their organization supports managers seeking to hire external contributors. Among Non-Orchestrators, only 39% report such support for managers. What’s more, Intentional Orchestrators are eight times more likely than Non-Orchestrators to strongly agree that their organization supports managers in the hiring of external contributors. (See Figure 5.)

At Novartis, Graf says, leaders are exploring new technologies and processes to support the increased need for external workers. “The mix is shifting toward more external and fewer internal people on our own payroll,” he says. “So it requires us to think, in terms of processes and technology enablement, ‘How do we tap into this pool of external resources?” At scale, especially in large organizations, managers and business units may need new resources, business processes, systems to access the workers they need.

For instance, greater dependence on external workers and specialized skills might require new mechanisms for authenticating or verifying the credentials of external talent (and internal workers as well). Organizations can support hiring managers by developing systems that do this. As Mary Lacity, Walton Professor of Information Systems and director of the Blockchain Center of Excellence at the University of Arkansas, says, “The current problem that we have today is when the holders of talent exaggerate or even lie about their skill sets. How do we do a better job at verifying the skill sets?”

Similarly, David Wengel, founder of iDatafy, the parent company of SmartResume, is building data consortia that support credential certifications. These consortia can assist hiring managers by enabling proactive outreach to job seekers with certified credentials by using advanced technologies and sophisticated data sharing. Managers in companies working to advance their orchestration of workforce ecosystems are increasingly relying on third-party organizations like this to establish acceptable credentials, and on related businesses to offer guidance on how to use and value these credentials.

4. Intentional Orchestrators are more likely to have leadership that understands how to allocate work for internal and external workers.

When asked to what extent their organization’s leaders understand which types of work are most suitable for internal or external workers, Intentional Orchestrators are roughly five times as likely as Non-Orchestrators to report that their leaders know how to distribute work between internal and external workers. (See Figure 6.)

At Novartis, leadership is beginning to think intentionally about the desired balance of internal and external workers, basing those decisions on the specific needs of the business. “We could do much more to weave the external availability of skilled talent into making decisions about how to resource specific work that comes up within the organization, considering aspects such as availability of skills, speed to access skills, and affordability,” Graf says.

Determining how to allocate work is an ongoing process at PlanOmatic. The company has approximately 50 employees and works with hundreds of contractors across the country. (Its workforce ecosystem also includes firms in India, Vietnam, and the Philippines that help fill post-production and administrative needs.) The company’s contractors, known as PlanOtechs, take professional photographs of properties for real estate investment trusts. Covrigaru says that because the real estate business is seasonal, with demand rising and falling throughout the year, the number of PlanOtechs “is fluid on a daily basis, almost. We’re onboarding PlanOtechs daily, scaling up and scaling down according to our clients’ needs. We’re really good at recruiting, maintaining, and scheduling a vendor network. That’s our bread and butter.” Regularly adjusting the balance between internal and external workers is essential to the company’s business model.

Covrigaru says that he and his chief operating officer have been discussing whether to add more full-time employees in some of the company’s heaviest markets. “We have tested and crafted this ecosystem of a workforce including all types of workers, from W-2s all the way to contractors overseas,” he says. “We have a lot of experience in shifting resources from one market to another. We have learned to navigate the waters, balancing between W-2 employees and contractors, and recognizing the constraints in various states. It’s constantly a challenge but definitely rewarding if it’s structured the right way.” For PlanOmatic, orchestrating its workforce ecosystem is a continuous, dynamic process.

5. Intentional Orchestrators are more likely to align their workforce with business strategy.

A strong majority of Intentional Orchestrators (86%) agree that their organization is effective at aligning their workforce with business strategies and objectives. Only 30% of the Non-Orchestrators believe that their organization is effective in this way. (See Figure 7.) This striking finding suggests that Intentional Orchestrators — with their expansive and inclusive approach — are more effective at aligning their workforces with strategic imperatives than organizations that pay less attention to orchestrating their workforce ecosystems. Coordinating efforts to fill an organization’s workforce needs (with various types of contributors) can lead to better alignment with business strategy.

Graf describes Novartis’s workforce as “those people who contribute to executing work against our purpose and business strategy.” In Novartis’s business environment, if you are part of its workforce, you are part of its purpose and strategy. Intentionally orchestrating a workforce ecosystem that includes both internal and external participants correlates with stronger organizational alignment.

More precisely, while it appears that Intentional Orchestrators have the upper hand when it comes to matching organizational behaviors to desired strategic outcomes, the benefits do not come strictly from organizational alignment. After all, many workers are not strictly part of the organization — but they are part of the organization’s overall workforce ecosystem. In a workforce ecosystem, linking an organization’s workforce structure with its business strategy may prompt leaders to think differently about what organizational alignment means in, and for, their organization.

Section 3: Orchestrating Workforce Ecosystems

To manage the varied, interconnected elements that constitute a modern workforce ecosystem, we suggest that leaders adopt an orchestration approach. To start, leaders should have a broad understanding of how the discrete participants in the structure work together to create value. Senior and business unit leaders should build an integrated perspective on how the entire workforce ecosystem operates. Meanwhile, functional leaders have crucial roles to play as well, often related to on-the-ground operational decisions. Working together, senior, business, and functional leaders can purposefully and systematically orchestrate the various players contributing to the ecosystem’s success. New interconnected relationships may require fundamental changes in management practices, technology, integration, and leadership.

New interconnected relationships may require fundamental changes in management practices, technology, integration, and leadership.

Workforce Ecosystem Orchestration Across Functions

Figure 8 depicts a set of concentric hexagons illustrating how organizational functions come together in a workforce ecosystem and address key activities and systems essential to workforce ecosystem orchestration. Around the outside of the shape are critical players, including senior leadership, business unit leaders, and functional areas. We organize these along three axes. We place senior leadership and business unit leaders on the vertical axis through the middle of the figure because these are primary orchestrators that generally need to take a holistic and integrated view of the ecosystem. We place human resources and procurement opposite each other on the top horizontal axis because these functions often have managerial responsibilities associated with gaining access to and managing essential contributors to the ecosystem. We place information technology and finance/legal opposite each other on the second horizontal axis because these functions serve crucial roles that enable the ecosystem to exist and operate effectively.

The four concentric hexagons represent cross-functional activities and systems vital to orchestrating workforce ecosystems. In the center is management practices because workforce ecosystems require fundamental shifts in how organizations approach some of their key practices. For example, many management practices are tied to the so-called employee life cycle model: acquiring, developing, and retaining full-time employees. In a workforce ecosystem, new management practices are often required to attract the best talent available, wherever it is, and to engage individuals and organizations via new approaches (such as using digital labor platforms to find individual contributors, or opening interfaces so independent software developers can create innovative apps to offer in an app store).

The second concentric hexagon, technology enablers, represents the systems and data that enable the management of all types of contributors. In most organizations, workforce-related technologies and data are fragmented: Different systems in different silos apply to different workforce contributors. One system might track contract labor within one functional area (such as IT), while another might manage a developer ecosystem that creates apps that augment a product’s functionality. Yet another system might track third-party distribution subcontractors. Orchestrating workforce ecosystems includes managing the technologies that serve both the organization and different types of contributors.

The third hexagon represents integration architectures. Leaders have decisions to make about how functional areas should work together so they can lead and manage their workforce ecosystems. We heard time and again from executives who see redundancies, gaps, and conflicts in how their organizations engage both employees and external workers. In some cases, different parts of organizations control different types of ecosystem relationships. For example, a strategic business development group may be responsible for strategic partnerships, whereas another group might own developer relations; without an integrated approach, this could lead to internal tensions and confused messaging to third parties. An integration architecture spans not only HR and procurement (for accessing external talent) but also other areas, such as IT (for data access, for instance), legal (for contracting), and finance (for allocations, invoicing, and payments). Additionally, leaders need to decide how they should coordinate relationships with external contributors — for example, choosing how rigorously they want to control third-party outcomes may lead to strict compliance testing for software apps.

The fourth and outermost hexagon represents leadership approaches. Leading workforce ecosystems may require significant shifts in leadership behaviors and mindsets. For example, since many participants in workforce ecosystems are external to the company — such as gig workers, subcontractors, and app developers — managers cannot exert the same types of direct control that they can with their own employees. In a workforce ecosystem, community-building within and beyond organizational boundaries and influencing without authority become critical elements of a leader’s toolbox. DEI principles and practices may need to be extended to external contributors. Leaders across all levels should reevaluate how they lead in a workforce ecosystem structure.

Building on this hexagon model, the remainder of this section discusses how various functions can work together to orchestrate their workforce ecosystems.

Leaders should articulate a vision not only for the future direction of a business, but also for how a workforce ecosystem will enable the execution of that vision.

Senior Leadership

Senior leaders play the critical role of setting an organization’s strategy, providing direction on companywide initiatives, establishing metrics, and generally serving as the final point of decision-making. To this list, we suggest that leaders add the responsibility of acting as the ultimate orchestrator of their organization’s workforce ecosystem. Leaders should articulate a vision not only for the future direction of a business, but also for how a workforce ecosystem will enable the execution of that vision.

Leaders should consider the extent to which the organization will rely on external contributors; this includes assessing its dependence on external organizations, such as subcontractors and app developers, which add value to its products and services. Whether or not the proper systems and resources are in place to support management’s dependence on external contributors, and whether managers have the right metrics and tools for assessing and driving the performance of those contributors, are additional considerations for leaders. Additionally, DEI initiatives are important topics that leaders should consider as they look at activities across the organization’s entire workforce ecosystem. Beyond incremental shifts in specific programs or practices, these workforce ecosystem-related issues reflect an expansive shift and, as such, suggest a new, more integrated, and holistic approach.

Most organizations are likely to already have a workforce ecosystem, since most organizations, at least to some extent, engage some types of external contributors. It may benefit senior leaders to recognize and assess the degree to which they depend on external contributors. For example, are external contractors already playing a mission-critical role? We’ve observed that some leaders are just beginning to recognize the degree to which their organizations already rely on contributors who are not their own employees. A valuable step for senior leaders may be to gain a shared comprehensive (cross-functional) understanding of the composition and operation of their organization’s workforce ecosystem today. Once that understanding is achieved, it may become easier (not easy!) to develop a shared understanding of the workforce ecosystem they would like to have in the future and how best to orchestrate it.

Business Unit Leaders

Business unit leaders face similar challenges because they own workforce ecosystem orchestration within their own business units. Along with larger strategic considerations, they are responsible for operational decisions affecting day-to-day performance. If business units do not coordinate their workforce ecosystems, alignment between strategic imperatives and tactical activities may suffer.

For example, suppose one business unit takes an inclusive approach to innovation and plans to publish interfaces (APIs) allowing third parties to create accessory products or apps to work with their offerings. If another part of the business takes a more closed or proprietary approach, this may cause conflicts for senior leadership to resolve, creating challenges both at the business unit and the senior leadership levels. This example highlights that decisions related to openness and types of engagements with external contributors can vary within an organization. This can be fine as long as efforts are integrated in such a way that they don’t confuse external contributors or frustrate internal employees — say, developers working on internal applications.

As with senior leaders, business unit leaders need to manage a variety of contributors who may be operating in different contexts with varying processes, rules, and norms. Because many of these contributors are external, leaders often have less control. For example, labor laws may prevent managers from providing comprehensive performance management to contractors. One way to address this dilemma is to concentrate leadership attention on areas that can be controlled — for example, developing and nurturing a more integrated culture that spans both employees and external contributors through more inclusive communication. Some leaders address the need to manage with less control by surrounding themselves with colleagues who are more adept at building community and motivating external contributors. They might also engage in executive education to ease the transition.

Across an organization’s leadership ranks, leadership development should be addressed, because what often makes sense in a hierarchical command-and-control context may not work in a more open, networked workforce ecosystem model. For example, much research has centered on the value of developing “T-shaped leaders” who have both deep, specific functional or product expertise and also broad organizational and/or industry knowledge. These types of leaders may be particularly adept at operating in a workforce ecosystem environment. Developing managers into T-shaped leaders may require new approaches, such as providing learning opportunities in other parts of the organization and offering access to opportunities outside the company that broaden their experience.4

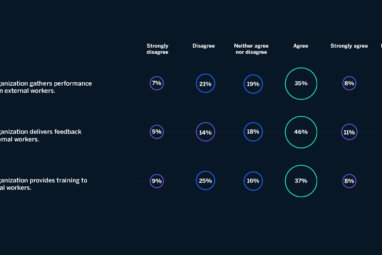

Human Resources

When we consider activities associated with sourcing, recruiting, engaging, developing, and broadly managing the administrative functions of a workforce, we usually go first to the human resources function. This group usually has responsibility for all aspects of human resources, including compliance, policy enforcement, and so on. But when a workforce is truly a workforce ecosystem consisting not only of employees but also external players — both individuals and organizations — how does HR’s role change? Many responsibilities of HR shift and lead to modified or new management practices. Workforce planning, talent acquisition, learning and development, career path development, performance management, and rewards all should be reconsidered as workforces expand beyond employees.

Whereas HR alone has traditionally addressed internal employee-related topics, as organizations move to workforce ecosystems, HR practices should become more integrated with other functional areas to encompass nonemployee participants. Though labor regulations make some integration impossible, one example of where integration can occur is with annual employee engagement surveys. Does it make sense to offer this feedback mechanism only to internal employees when a large percentage of contributors may not be hired employees? Additionally, functional areas are increasingly engaging external workers on a project basis via, for example, digital labor platforms (as opposed to hiring full-time employees) and managing these engagements through the procurement function; in those cases, to what extent should HR get more involved? Similarly, the customary notion of training employees for specific jobs and particular roles in an organization may give way to more continuous, self-directed development opportunities for both internal and external contributors that are geared toward enabling people to grow themselves for their own benefit as well as the organization’s.

Whereas HR alone has traditionally addressed internal employee-related topics, as organizations move to workforce ecosystems, HR practices should become more integrated with other functional areas to encompass nonemployee participants.

Conventional HR leaders may not have the experience to operate in a more networked and interconnected world managing myriad types of internal and external contributors. If they have progressed in their careers entirely within the HR function, they may need development opportunities to acquire more appropriate skills and new experiences. For example, an HR leader who has spent years in that department might benefit from exposure to other business areas. Such experiences can enable the leader to work more collaboratively with leaders in other functional areas (such as finance) that suddenly have a prominent new role in orchestrating the workforce ecosystem.

As workforce ecosystems develop, HR is likely to lose control in some areas where it has traditionally held sway; business units and functional areas are increasingly able to find and engage resources on their own, outside traditional employee-centric models. But HR may gain new opportunities to contribute as its scope increases to include engagement with external contributors. For example, HR may begin to create policies, programs, and resources to shift to enterprise-level people management. Finally, HR could play a key role, along with partners like the procurement function, in shifting practices to focus on accessing, growing, aligning, and connecting external contributors.

Procurement

When managers think of the procurement function, they often envision cost-cutting activities and contracting for materials used to create products and services. Often, however, procurement not only sources and contracts for goods and services but also engages with external contractors, subcontractors, professional services organizations, and the like. As these groups account for an increasingly large percentage of an organization’s workforce, procurement may begin to play a more central and strategic role. Will procurement become a more critical partner for accessing and engaging talent? If so, then the relationship between procurement and other functions may need to be reevaluated.

Information Technology

Technology plays a variety of pivotal roles in the emergence and management of workforce ecosystems. Workforce technologies such as HR systems, contractor management systems, and talent marketplaces serve as critical infrastructure and enable close coordination across functions in the management of internal and external contributors. Other technologies can help workers accomplish their tasks more efficiently, such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and Slack. Emerging technologies contribute to our ability to verify credentials such as diplomas, certificates, badges, employment history, and so on. Blockchain, AI, machine learning, and other classes of technologies are often critical to these systems. Finally, technologies in the form of robots and chatbots increasingly play essential roles as members of workforce ecosystems. All of these technologies, while distinct from one another, contribute to the operation and orchestration of workforce ecosystems.

Some of these technologies and systems are managed entirely within specific business units or functional areas, while others are managed, at least to some extent, by IT. As with the other functions, the IT group’s role may need to change in fundamental ways as workforce ecosystems increase in prevalence.

IT leaders need to have deep technical knowledge of course. But as the span of the organization widens, they also need to grasp the complexities of business strategy and technology’s role in enabling and often driving those strategies. Beyond providing tools and systems, IT needs to understand the evolving critical role of data in highly interconnected workforce ecosystems. Business managers increasingly rely on sophisticated data and analytics, including both customer insights and extensive internal metrics, to steer their organizations. In a workforce ecosystem, much of that data resides outside the organization — for example, in the work histories, credentials, and reputations of external contributors. The IT function and its leaders are charged with ensuring the efficacy of that data, appropriate access to it, and integration between disparate systems. As organizations become more integrated in their approach to workforce ecosystems and more sophisticated in how they orchestrate them, IT functions should in turn reexamine their roles and activities.

Finance/Legal

The finance and legal functions serve roles that are essential to the successful implementation and orchestration of workforce ecosystems. Finance, with its overarching responsibility for overseeing budgetary allocations, is involved in discussions related to types of contributors to the organization and the various costs associated with them. Additionally, the finance function is involved in discussions of new systems and tools to support workforce ecosystem orchestration.

In addition to managing risk considerations, the legal function should be intimately involved both in contracting with the various members of an ecosystem and also with intellectual property considerations. Especially in the domain of intellectual property, there are many intricate questions related to which types of licensing to deploy. These topics are routinely addressed in any type of multiparty partnership or alliance, but in workforce ecosystems, the volume and complexity of these questions can increase dramatically.

Conclusion

Many organizational functions share responsibility for orchestrating workforce ecosystems. Leaders need to decide how to structure relationships among these functions to effectively manage these interconnected, complex systems. Some of these functions, like procurement and legal, may require special effort to be included in, or integrated into, the workforce ecosystem orchestration process. Intentionally leading and managing workforce ecosystems can improve how organizations achieve their strategic goals, now and in the future. To orchestrate a workforce ecosystem is to take the reins of your organization’s future.

About the Research

Our research findings are based on a global executive survey, interviews with thought leaders in academia and industry, and library research. In the fall of 2021, we surveyed 4,078 managers in 129 countries. They collectively represented 29 unique industries. We also interviewed 19 executives and thought leaders.

Using survey responses, the research team calculated an orchestration index that grouped organizations into three categories: Intentional Orchestrators, Partial Orchestrators, and Non-Orchestrators. Three criteria were used to determine these categories: (1) how broadly respondents defined their workforce, (2) degree of integrated management of internal and external workers, and (3) degree of preparedness for managing a workforce comprising more external providers. The three measures were summed into a single score. The scores were split using one standard deviation from the mean of each index before categorization. Intentional Orchestrators represented 22% of the sample, Partial Orchestrators represented 60%, and Non-Orchestrators represented 18%.

Comment (1)

Kumar Venkatesan