Did Jack Welch Blow Up the Business World?

A recent book lays the blame for two generations of shareholder capitalism at the doorstep of the late Jack Welch, but this ignores broader structural and societal pressures at play.

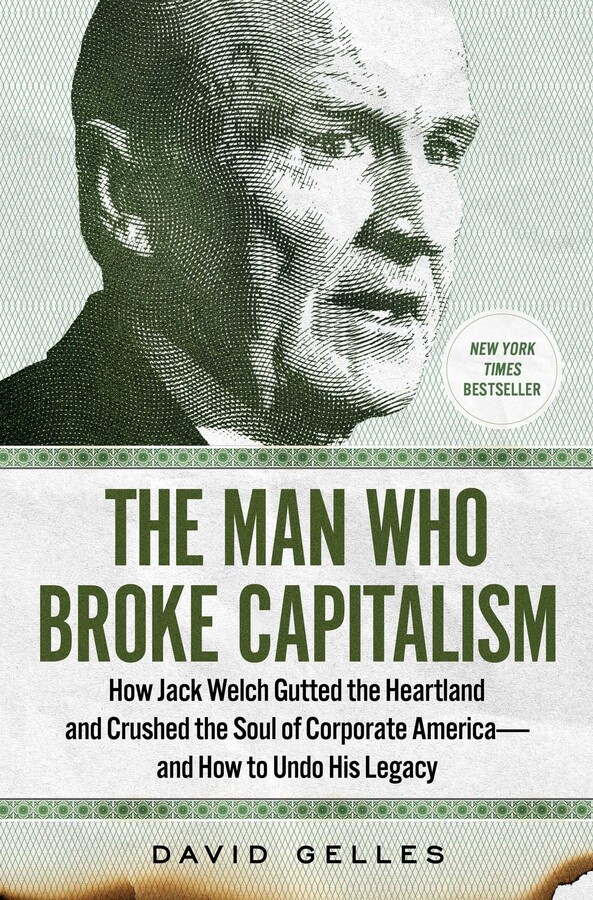

The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America — and How to Undo His Legacy

David Gelles (Simon & Schuster, 2022)

“The history of the world is but the biography of great men,” wrote 19th-century Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. With The Man Who Broke Capitalism, New York Times business reporter David Gelles attempts to resuscitate the hoary “great man” theory of leadership in a backhanded sort of way. He calls out the late Jack Welch, the General Electric CEO whom Fortune magazine anointed “manager of the century” in 1999, as the evil mastermind behind the litany of economic woes rooted in shareholder capitalism gone wild, but he pays scant attention to their root causes.

When Welch took up the reins at GE in 1981, it was not a prosperous time in America’s economic history. The post-World War II boom was on its last legs: America’s industrial giants were sinking under their own weight, and foreign companies, especially those from Japan and Germany, were making inroads the size of superhighways into the U.S. consumer market. GE, then one of the nation’s leading companies, was languishing in the slow growth environment too.

If you were in business in the 1980s and ’90s, Gelles’s recounting of Welch’s tenure at GE will be a familiar story. “Neutron Jack” cut head count and instituted an annual employee ranking scheme that required that employees in the lowest decile be fired. The company’s business units had to be No. 1 or 2 in their market or they were jettisoned. Meanwhile, Welch chased new growth opportunities in financial services and media — soon, GE Capital alone accounted for more than half of the company’s profits.

The results? “During [Welch’s] tenure, GE posted annualized share price growth of about 21% a year, far outpacing the S&P 500 even during a historic bull market,” writes Gelles. “When Welch took over, GE was worth $14 billion. Two decades later, the company was worth $600 billion — the most valuable company in the world.”

This extraordinary run made Jack Welch a legend in his own time. Gelles reports that 8,000 or so articles about Welch appeared annually during his final years at GE — “most all of them fawning in tone.” Major companies across the country vied to hire his proteges as their CEOs. (Some of these companies profited, but many did not.) Meanwhile, GE made Welch one of the world’s richest people: “In 2000, his last full year on the job, Welch’s compensation package was worth $122.5 million,” relates Gelles. “A career of stock-based compensation had paid off. In the end, Welch possessed a staggering 21 million shares in GE, which, at their peak, were worth roughly $1 billion.”

The difference in Gelles’s telling of Welch’s story is its almost exclusive focus on the negative externalities. He argues that Jack Welch’s approach to corporate management relied on the “dark arts” of downsizing, dealmaking, and financialization — the last of which nearly sank the company when the crisis in subprime lending crashed the global economy a decade after Welch retired. Gelles labels this trio of tactics “Welchism” and throughout the book blames Welch for popularizing it and propagating its costs on the American worker and economy.

These costs are well known and undeniable. In 2009, Welch himself denounced shareholder capitalism as “the dumbest idea in the world” — to which Gelles responds, “Coming from Welch, the assertion was laughable.”

But is Jack Welch the bogeyman who single-handedly gutted American manufacturing and innovation and turned the American dream of millions of workers and middle managers into a waking nightmare of stagnant wages and meager retirements? Hardly. Welch carried water for economists such as Milton Friedman, politicians like Ronald Reagan, and the people who supported them — that is, powerful and wealthy investors who cared about nothing except rising returns. There were structural forces in play, too: the growing economic might of Japan, Germany, and then China; free trade and deregulation; the decline of unions and the rise of global labor arbitrage; and an overly permissive government. Welch is not responsible for the societal zeitgeist portrayed in movies like Oliver Stone’s Wall Street. He rode a wave, and perhaps he helped increase its amplitude, but he didn’t create or control it. No one person could, no matter how great.

During a recent interview with Roger Martin, the former dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, who is quoted several times in Gelles’s book, I asked for his assessment of Welch. Martin knew him from Welch’s visits to the Rotman School and had taught at GE University by invitation of the CEO. “I find it hard to see him as a Machiavellian genius,” said Martin. “He was an unsophisticated connoisseur of the idea of shareholder value maximization who was able to somewhat blindly and without reflection implement it in a powerful company.”

While The Man Who Broke Capitalism serves as a welcome antidote to the shelf full of hagiographic books about Welch, including his memoir and management manuals, it also is a tiresome polemic and a misreading of modern business history and the shareholder-obsessed culture of management that emerged in the 1980s and ’90s. Worse, in seeking to transform Jack Welch into the straw dog for a couple of generations’ worth of greed, selfishness, and shortsightedness, Gelles ignores the broader structural and societal pressures that resulted in the creation of an economic system that has proved to be inequitable and unsustainable.