Inside the World of the Project Baron

In many industries, project-based firms — companies organized around completing customized projects for clients — are common. New research offers insights into the leadership — and politics — that typify these organizations.

In industries such as architecture, most individual businesses are “project-based” firms.

In industrial sectors such as consulting, advertising, filmmaking, software, architecture, engineering and construction, most individual businesses are “project-based firms”1 — in other words, their activities tend to be organized through the delivery of projects aimed at meeting the highly differentiated and customized needs of clients.2 These firms depend on executing discrete task-oriented packages for clients, often through temporary coalitions with other project-based organizations,3 and on routinely combining knowledge and skills in new ways.

Of course, as with any business, project-based firms need to maintain internal coherence. But they also require flexibility to respond to opportunities, manage workloads and allocate resources to different projects. As a result, this type of organization, which is becoming increasingly common in developed economies, presents special management and leadership challenges. Research on this subject has been dominated by singular projects as the units of analysis.4 By contrast, this article focuses on the leadership, structure and governance of the firms that deliver those projects.5

The Leading Question

How do project-based firms resolve the tensions between flexibility and control?

Findings

- The level of centralized control in project-based firms varies widely.

- Executives who lead the organizational units that deliver projects can be thought of as “barons” — powerful individuals who often exhibit competitive, protective and entrepreneurial behavior.

- In more decentralized firms, project barons often “squirrel” away resources — such as money or knowledge — to keep them for their unit’s use rather than share them.

This article draws on more than 200 interviews with project managers and company leaders conducted in 40 project-based firms in eight countries. (See “About the Research.”) We propose the concept of “baronies” to describe the organizational units that execute the projects within project-based firms. The term arose when an interviewee claimed that “we are the barons running the business,” and it emerged in a number of subsequent interviews and workshops as well. This metaphor is appropriate because it describes entities that often are led by powerful individuals who exhibit the baronial characteristics associated with competitive, protective and entrepreneurial behavior. It also suggests the political nature of resource allocation within project-based firms.

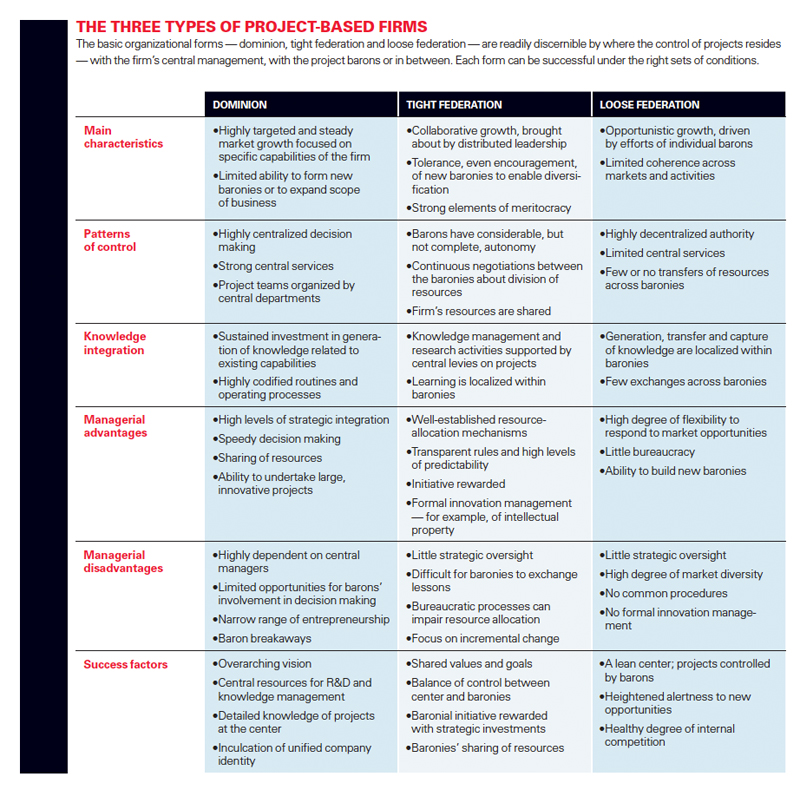

Such baronies are also characterized, however, by a continual tension between coordination and control on the one hand and flexibility and responsiveness on the other. This tension lies at the heart of project-based organizing and is key to understanding the challenges associated with their leadership and management. In this article, we offer a framework for understanding the forms of governance by which the tensions between flexibility and control are resolved in different types of project-based firms, based on three basic organizational forms: “dominion,” “tight federation” and “loose federation.” (See “The Three Types of Project-Based Firms.”) Further, we explore a second dimension regarding the extent to which each governance system integrates knowledge across the organization as a whole.

The Three Kinds of Baronies

Dominions, tight federations and loose federations vary according to the location of decision making about control. In each case, the relationship between the center of the organization and its baronies is embedded in a complex process of governance — a “settlement” — that is continually negotiated as different baronies compete for resources and contest the results. Such settlements help to reduce overt conflict between different interests within the organization, setting mutually agreed bounds on actions and behaviors.

Dominions Firms with a dominion governance structure have a single point of decision making to which barons defer. Dominions are, in some respects, similar to Louis XIV’s Versailles or the Medicis in 15th-century Florence.6 In this pure type, all baronies must respond to strict management procedures laid down from the center. As a result, dominions tend to have stable patterns of ownership; they are often family-owned or controlled by shareholders who stipulate tight performance targets.

While the management of projects is decentralized, dominions tend to rely on highly codified routines and operating procedures to maintain centralized control. For example, one large U.S.-based engineering firm we studied had extensive procedural systems for project execution that detailed the project management structure and the activities that project managers must undertake. A number of firms had similarly developed project rule books that specified procedures for launching and executing projects. Although such a codified set of rules can be difficult to follow in practice — “No two projects are alike,” observed one interviewee — the value of the rule book is as a reference source and a means of displaying procedures externally. It represents the template of the organization’s ways of working and of solving problems.7

Some project-based firms have a single point of decision making to which project barons defer — an arrangement similar in some respects to Louis XIV’s Versailles.

It is common for project managers in dominions to be moved from market to market, shifted from running projects in sectors ranging from the design of chemical plants to the construction of railways. For example, the U.S. firm cited above has an explicit policy to ensure that project managers move across industries. One interviewee commented that the firm’s business was the management of projects and that the particular industrial sector made little difference to project execution. “A good PM [project manager] in petrochemicals,” he maintained, “will be a good PM in railway construction.”

Tight Federations Unlike their counterparts in dominions, barons in tight federations have considerable autonomy with respect to project creation and execution. These firms are often held together by strong patterns of affinity and consensus between barons, even though they may have different technical capabilities and work in different market segments. For example, in one large U.K.-based engineering design firm, many of the senior managers and group leaders, having collaborated on projects before, find themselves united in a common cause to develop and extend the organization. Other cultural factors, such as allegiance to the notion of design excellence, also bind baronies tightly together.

In tight federations, it is common to move personnel between different parts of the organization. When labor is scarce within the firm there can be competition for staff, and it is not uncommon for one barony to poach workers from another. Any resulting conflicts are usually resolved by central management. The extent of multilateral labor pooling and sharing across the federation under more normal conditions, however, indicates the degree of cohesion and trust among the baronies.

Central departments are well-developed in tight federations, controlling a wide range of activities inside the organization, such as human resources, sales and marketing, R&D and finance. These functions are supported by levies on projects, at rates agreed to by the barons. The center also frames the use of funds to launch new baronies or invest in established ones.

Making or adhering to agreements in tight federations can be a fractious process, as it is not unknown for barons to rebel against the settlement and behave opportunistically, sometimes withholding information and resources from other parts of the firm. However, the settlement allows for collective decision making and therefore provides some glue to hold disparate parts of the organization together.

Loose Federations Loose federations are characterized by strong barons, weak central control and low levels of central services. The loose federation is more flexible than the other two basic types. It can be relatively easy to sustain in stable markets because the costs of central management are low and there is limited central control. However, central investments in new activities are limited, with the baronies largely being left to their own devices.

Barons within loose federations thus have considerable autonomy. They independently bid for, and manage, their own projects and resources. We have even observed different parts of a loose federation bidding competitively for the same job. Given that baronies lack central oversight and a sense of common purpose, the larger organization of which they are part remains remote, acting more as a trading company than a unified business. Each barony aims to expand itself, even at the expense of the other baronies. In this environment, it is difficult for senior managers in central departments to influence behavior. As one main board director of a loose federation commented, “I can’t tell anyone what to do in my organization.”

In some loose federations, we have observed attempts by the center to assert control over the baronies. But these efforts, which go against the settlement that accords strong decision making rights to the barons, often end in failure. In one case study organization, when a person from a nonproject-based environment was brought in to lead the company, he attempted to confront the power of the baronies and create a tight federation. The barons rebelled, and the manager was removed from the firm.

Clearly, the barons in loose federations rule; they jealously guard their power base, and governance is formally based on a mutual agreement not to challenge each other’s authority. In addition to being responsible for project management, execution and team development, barons often control human resources and financial systems as well, although these latter elements are usually based on common procedures and platforms.

In loose federations, baronies therefore have their own sense of identity, and they can even have a name different from that of their parent organization. The primary loyalty of staff is to their barony, and interbarony exchanges of skills and resource pooling are uncommon — and in many of these firms, nonexistent. We have even found cases where barons explicitly instructed their staffs not to help members from other baronies on common problems. As one such baron put it, “We do not return their phone calls.”

Three Areas of Management Behavior

The three types of governance of project-based firms have implications for three key kinds of management activity: synthesizing (learning across projects); spawning (creating new entrepreneurial initiatives, units and spinoffs); and squirreling (protecting resources for discretionary uses).

Synthesizing Synthesizing is the capacity for the organization to learn across projects — to draw on experience in one project for use in another. It is the ability to draw together the lessons from different projects into an integrated whole.

Project-based firms with a dominion structure are well-positioned to build on such experience, but project synthesis is a difficult task even for them. Much effort is routinely devoted to capturing and codifying project data, using case studies and feedback instruments, and communicating such information to the rest of the company. However, there is no unanimity on the best way to accomplish these objectives. For example, in one of the dominions we studied, at the end of each project, managers prepared a detailed history that included all of the project’s documented records as well as more informal staff commentary. However, in interviews, these managers argued that the most effective mechanisms for capturing lessons were annual retreats among the organization’s managers, the continuous movement of managers from one market to another and mentoring by senior staff.

The clustering of activities around specific capabilities allows dominions to benefit from central investment in support tools and techniques, and the dominion structure helps to ensure the funding of such support. For example, it is possible to develop firmwide software tools and packages by sharing the capital costs of these investments across a wide range of projects. One of the dominions in our study invested in visualization technologies that were used in project planning and execution across a range of markets, though technical support tended to be highly formalized and institutionalized. Many dominions operate R&D groups, which also are paid for by central levies on individual projects. This provides a resource for the whole firm to draw on in new projects, although the content of the R&D activities is largely determined centrally.

In tight federations, technical support functions often lie at the heart of the business’s knowledge base. For example, in one firm we studied the central knowledge-management function invested in activities to expand the firm’s capabilities and provided a range of services to project teams across the organization. But several of the tight federations we observed did not formally invest in developing new knowledge, such as through R&D. They devoted resources instead to tools — such as electronic project libraries publication in internal and external journals and people-finder databases — for project support and information exchange.

Other central services of tight federations include the pooling of information technology; the adoption and use of common sets of practices, design platforms, quality assurance procedures, simulation tools and design training studios; the human resources function; and other resources to help sustain and support the firm’s work. But regardless of the central services available to support dialogue throughout the firm, we found the degree of exchange between the baronies in tight federations to be limited. Our interviews suggest, in fact, that if the spirit of unity is weakened over time, the settlement underpinning this kind of governance system can break down altogether. To sustain the tight federation, it is necessary to continuously find commonality across the baronies and to seek opportunities to take collective action.

In loose federations, the governance structure provides for only a few central services, such as financial management, that are funded by levies on baronies. If the baronies are profitable, they contribute their required levies to central management, but there is little pressure on them to conform to any behavioral rules inside the organization. Profitable baronies operating in a loose federation invest in their own R&D or other technical support activities at the local level. As a result, it is common to see considerable differences in technical capability and facilities across the organization’s baronies. Moreover, a mechanism is at work to maintain organizational health. We found that the loose federation often moves quickly to close down unsuccessful baronies. Because there are limited central funds and a general reluctance to support ailing baronies, if a barony fails, it fails alone.

Spawning Spawning is the creation of new entrepreneurial initiatives in project-based firms. These are generally new internal units but may also be spin-offs. Firms organized as dominions have limited scope for such entrepreneurialism, so in such firms, it is common for technical groups and project barons to periodically spin off to form entirely new businesses. These actions often reflect the desires of individual barons to develop and control their own enterprises — in contrast to the dominion’s overall strategy of strong control by the central organization.

Such attempts at individual control can come at a cost, however, as the spawning of new firms often leads to conflict with the central authority in a dominion firm. In one extreme example we discovered, once a baron had moved to create his own firm, central management deemed him such a nonperson that he was digitally excised from company photographs. Even when an entrepreneurial initiative is allowed, it is usually closely vetted by the central organization before a baron can proceed to explore the opportunity. In this sense, there is little bottom-up entrepreneurialism in dominions.8 This helps to ensure that new units will not upset the coherence of the organization and take it away from its well-established templates and routines.

However, when a dominion does seek to enable or support entrepreneurial activity, it can apply considerable resources to the task, drawing skilled individuals from across the organization to the new venture. Its infrequent spawning efforts tend not only to be large-scale but also potentially more

successful than the relatively undirected and underresourced efforts of tight and loose federations. And dominions’ spawning efforts tend to focus on carefully considered diversification, the result of weighing new opportunities against existing know-how and resources.

In tight federations, the spawning process also involves a degree of central oversight, but this tends to be limited in nature. Barons in tight federations are regularly given opportunities to spawn new activities; as long as their efforts do not infringe on those of other barons, they are free to proceed, and in many cases their attempts are only partially monitored from the center. When barons do come into conflict, it is generally regarding the direction of the firm. In such situations they may either try to renegotiate the settlement — to reset the boundaries of the organization and perhaps the relationships between its units — or simply accept the rejection of their idea. In our research, we found several tight federations that spurned opportunities for spawning new units or products because the proposed activities were considered too distant from the firm’s operating routines and traditions.

However, when a tight federation does decide to commit to a new activity, it can partially reshape the central resources of the firm — such as its investments in knowledge management — to support such a venture. The firm’s willingness to allow entrepreneurialism also entails the prior approval of the other barons; in effect, barons have veto power over the ambitions of their counterparts. All in all, entrepreneurialism in the tight federation can be a continuing source of tension.

In a loose federation, spawning is explicitly conducted at the level of the barony. Barons are free to pursue whatever opportunities they choose, with little or no input required from the other barons. Such bottom-up entrepreneurialism is not necessarily an unmitigated good. For example, we have seen cases in which the absence of coordination in entrepreneurial efforts resulted in failure because the resources and skills deployed to exploit the opportunity were too modest for the task. On the other hand, loose federations are often able to successfully house baronies that seek to deviate from the efforts of the firm’s other baronies. This means they are liable to diversify the organization, sometimes more than central management might wish.

Squirreling We found that barons sometimes collect overheads from their projects, thereby creating — and frequently concealing — surpluses to reinvest in their own domains. The act of taking these set-asides was called “squirreling” by interviewees — an analogy to a squirrel hiding nuts from others for its own later consumption. We have found widespread evidence of squirreling resources — money, space (allocation of offices) and knowledge (people withholding ideas for their own gain) — especially in tight and loose federations.

Squirreling allows barons to direct resources without having to compete for them against other baronies, and it circumvents the control of central actors. But we found that as the incidence of squirreling increases, so does the level of tension in the organization. If this trend continues, the governance structure begins to break down, and there may be continuous struggle among the barons regarding the allocations of resources between the project teams and the center.

Dominions, unlike other types of project-based firms, have few independent financial centers inside the organization and therefore present few opportunities for project baronies to develop surpluses that could be used to finance new ventures of their choosing. If barons inside dominions are caught squirreling, they may be subject to organizational sanction, including dismissal. In one firm we studied, all residual accounts of each barony were “zeroed” at the end of each financial year to ensure that no unit could hold over funds. In this way, dominions control future investments and any financial slack in the organization.

In tight federations, there is greater scope for barons to squirrel away resources in order to be entrepreneurial. Financial systems may actually allow barons to put aside their own resources from one accounting period to the next as long as they have made their required contributions to the center; many of the barons would balk at committing surplus funds to the central part of the firm with only a modest chance of seeing them reinvested in their barony. Baronies often maintain separate accounting systems to facilitate the top-slicing for their own unit. In many of the organizations we studied, central management often has a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy on these practices and hidden resources.

Loose federations, we found, are characterized by endemic squirreling, as each baron stands alone and receives only modest support from the center. Indeed, it is not uncommon for these barons to make elaborate and sophisticated efforts, sometimes through subversive means, to retain surplus resources. Thus managers at the center of loose federations often find themselves engaged in “cat and mouse” games with the barons. In some organizations, we observed senior managers literally throwing up their hands when asked what they could do to overcome squirreling; they have simply resigned themselves to this kind of behavior.

Comparing the Types of Baronies

We now turn to the advantages and disadvantages of each type of project-based firm. Essentially, the higher the level of centralized control over the work in the baronies, the greater the associated potential for integration — what we describe as synthesizing — of project experiences. In the cases of dominions and tight federations, which expend considerable resources on knowledge management, both forms need to ensure organizational coherence to get good returns on their investments. Dominions in particular maintain rigorous control over the baronies, but in so doing they lose flexibility and responsiveness. This sometimes results in breakaways by entrepreneurial barons wishing to control their own domains.

Tight federations have the potential to invest in new initiatives and to shift resources across the baronies — but they must endure continual negotiation with barons over the levels of support for central services. Thus tight federations’ ability to perform central tasks is dependent on the settlement with the barons, although conflicts over the allocation of resources can persist. When the situation deteriorates to the point that barons rebel, the tight federation can fragment altogether. In other words, this organizational form can be unstable and difficult to sustain, particularly when the firm tries to expand into new markets.

In contrast, loose federations are decentralized and highly flexible. The responsibility for ongoing operations is located within the baronies, and barons have a relatively free hand in their domains’ future development. But there are few intrafirm exchanges of resources. Knowledge is therefore localized, and there are limited possibilities for learning across the organization.

Dominions’ baronies are often led by extraordinarily talented individuals, but their strength is also the organization’s weakness. Such individuals are hard to replace, and their personalities, sometimes smacking of hubris, may alienate important clients, prevent some contracts from being won and deter gifted managers and engineers who might otherwise wish to work on the barons’ projects. A major attraction of working in dominions is the potential to acquire deep expertise in particular specialties, but this advantage can be limited by managers’ restricted opportunities to exercise autonomy in decisions and discretion over tasks. Given that their voices are seldom heard, managers may ultimately conclude that their career progression requires exiting the firm.

Tight federations, by contrast, welcome initiative, but their innovativeness tends to be incremental in nature. Strategic oversight is limited, and diversification primarily depends on the emergence of new baronies. Although there is some degree of integration in tight federations — they have efficient management processes (for example, in the area of intellectual property protection) — synthesizing remains difficult. The distributed leadership of tight federations can be constrained by too much procedure and bureaucracy, and occasional fractiousness can break out.

Loose federations have considerable flexibility, and they impose little in the way of bureaucracy, common procedures or rules. As a result, innovation occurs frequently, though often in an ad hoc manner. Although prospects are good for building new baronies, this can depend on extensive squirreling, which may not be in the overall organization’s best interests. Careers can be diverse and exciting, but they may also be short: The individual baronies stand or fail without central resources to facilitate transitions.

Success Factors

Success in each type of project-based firm depends on conforming to the appropriate practices within its particular governance structure — or, alternately stated, on avoiding inappropriate practices. Squirreling in dominions would do little for career progression; large-scale spawning in tight federations would not likely be supported; and synthesizing in loose federations would be thankless.

Important for dominions is an overarching vision of the company, particularly regarding its key unifying characteristics and the markets it addresses. And, true to dominions’ nature, a high degree of strategic oversight and control by centralized departments is required across the firm’s activities. The training system inside dominions therefore focuses not only on the development of skills in the core areas of the firm but also on helping to inculcate staff with a sense of company identity. One firm we studied operates a training system based on a “project ladder.” Junior staff are assigned to small projects; as their levels of experience increase, they are given larger and more complex projects. The status of the firm’s employees is measured by the size of their projects — the bigger the project, the more senior the staff member.

In response to new project opportunities, the central management of dominions creates project teams by moving resources from across the organization. This form of control thus requires managers at the center to have detailed knowledge of both projects and staff capabilities organizationwide and to have the authority to shift these capabilities between the different types of projects as needed. Such knowledge and authority, interviewees suggest, are integral to the success of the business.

In tight federations, success crucially depends on the development of a unified culture — the building of shared values around commonly agreed-upon goals. This requires (a) continual reinforcement of the settlement that balances resource allocation between the barons and the center; and (b) the incentivizing of barons to share their surpluses. Barons are encouraged to do so through rewards for entrepreneurial initiatives in areas that are diversified but also sufficiently related to the company businesses.

Successful strategies in loose federations are those that allow many flowers to bloom. Initiative is encouraged without prescriptive direction from the center, whose activities are encouraged to remain lean. Advantages lie in the heightened awareness of market opportunities — loose federations are strongly market-facing — and the capacity to reward barons by allowing them to capture the profits from their new initiatives. Loose federations also derive benefits by striking a particular balance: encouraging competitive rivalry between the baronies, which helps keep them lean and mean, while preventing such internal competition from going too far and becoming destructive to the baronies involved and the firm.

Our research shows that project-based firms must find the models of governance and structure most suitable to the markets in which they operate, and that governance and structure are based on a trade-off between control and flexibility as firms align internal decision-making processes and external market opportunities. But we do not claim to offer the last word — the management of project-based organizations is worthy of considerably greater research attention. For example, we did not explore the changing and sometimes dual roles of project leaders and barons within these firms, nor whether firms may evolve through different types of organizational forms over time as they age, nor whether the nature of governance at any given time limits the possibilities for changes in organizational form.

References

1. See, for example, R.J. DeFillippi and M.B. Arthur, “Paradox in Project-Based Enterprise: The Case of Film Making,” California Management Review 40, no. 2 (winter 1998): 125-139; M. Hobday, “The Project-Based Organisation: An Ideal Form for Managing Complex Products and Systems?,” Research Policy 29, no. 7-8 (August 2000): 871-893; A. Davies and T. Brady, “Organisational Capabilities and Learning in Complex Product Systems: Towards Repeatable Solutions,” Research Policy 29, no. 7-8 (August 2000): 931-953; and D.M. Gann and A.J. Salter, “Innovation in Project-Based, Service-Enhanced Firms: The Construction of Complex Products and Systems,” Research Policy 29, no. 7-8 (August 2000): 955-972.

2. M. Hobday, “Product Complexity, Innovation and Industrial Organisation,” Research Policy 26, no. 6 (February 1998): 689-710; D. Dvir and A. Shenhar, “What Great Projects Have in Common,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52, no. 3 (spring 2011):19-21; and A. De Meyer, C.H. Loch and M.T. Pich, “Managing Project Uncertainty: From Variation to Chaos,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 2 (winter 2002): 60-67.

3. A. Keegan and J.R. Turner, “The Management of Innovation in Project-Based Firms,” Long Range Planning 35, no. 4 (August 2002): 367-388.

4. M. Engwall, “No Project Is an Island: Linking Projects to History and Context,” Research Policy 32, no. 5 (May 2003): 789-808.

5. J. Cummings and C. Pletcher, “Why Project Networks Beat Project Teams,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52, no. 3 (spring 2011): 75-80.

6. J.F. Padgett and C.K. Ansell, “Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400-1434,” American Journal of Sociology 98, no. 6 (May 1993): 1259-1319.

7. S.G. Winter and G. Szulanski, “Replication as Strategy,” Organization Science 12, no. 6 (November/December 2001): 730-743.

8. R.A. Burgelman, “A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm,” Administrative Science Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1983): 223-244.

i. A. Salter and D. Gann, “Sources of Ideas for Innovation in Engineering Design,” Research Policy 32, no. 8 (September 2003): 1309-1324; Gann, “Innovation,” Research Policy 29, no. 7-8 (2000); A. Davies, D. Gann and T. Douglas, “Innovation in Megaprojects: Systems Integration at London Heathrow Terminal 5,” California Management Review 51, no. 2 (winter 2009): 101-125; M. Dodgson, D.M. Gann and A. Salter, “‘In Case of Fire, Please Use the Elevator’: Simulation Technology and Organization in Fire Engineering,” Organization Science 18, no. 5 (September/October 2007): 849-864; and S. Bayer and D. Gann, “Balancing Work: Bidding Strategies and Workload Dynamics in a Project-Based Professional Service Organization,” System Dynamics Review 22, no. 3 (winter 2006): 185-211.

Comment (1)

petri